Words and Photographs by Phil Johnston

Be advised: This article contains graphic images of animal remains.

Whether you are a wildlife biologist, cattle rancher, small organic farmer, or just an outdoor enthusiast, learning to accurately interpret the feeding signs of carnivores can enrich your natural experience, protect your livelihood, and ensure accuracy in data collection for wildlife research and management. Centuries of folklore and decades of Hollywood films have portrayed carnivores as blood-thirsty killing machines, slaughtering livestock and humans for sport, and the average person in the 21st century gravitates towards the most dramatic and fearful explanations when encountering a carcass in the woods. I have seen people swear that a deer they found had been killed by a mountain lion despite the complete lack of feeding sign on the carcass and the presence of a highway just yards away. Interpreting the feeding signs of predators and scavengers can quickly become immensely complex, especially when multiple species have shared a carcass, but understanding the behavior, feeding mechanics, and preferences of different species can allow you to untangle intricate stories of predation, scavenging and kleptoparasitism. The word “kleptoparasitism” refers to when one animal steals the food obtained/gathered/killed by another, and this ecological interaction plays a major role in shaping the feeding behaviors of different predators and scavengers. Now might be a good time to warn you that this article contains extremely graphic pictures of dead animals in various states of mutilation and decay, so if you would rather not see such things scroll no further.

Click on images to view the high quality, full-size version.

Let’s start with the basics. Larger animals cause more significant damage to carcasses, and smaller animals cause less significant damage and leave more parts behind. This intuitive fact is apparent from prey items as small as sparrows to as large as elk. When a sharp-shinned hawk eats a varied thrush, the many body feathers must be removed as each small downy feather would be an awkward, non-nutritive mouthful for the small hawk, and thus when investigating the kill-site you will find nearly every single body feather neatly removed and piled on the ground. When a mountain lion eats a varied thrush, the small amount of meat on the bird is certainly not worth the time it would take to remove every single feather, and each individual feather does not represent nearly the same level of gastronomic hardship for the lion as it would for the sharp-shin, and in fact the lion will pretty much eat the bird whole, leaving behind a handful of flight feathers and whatever body feathers just happened to fall off as the bird was gobbled up.

When a mountain lion feeds on a deer carcass, many of the largest bones in the body will be crunched and partially or entirely consumed, including vertebrae, femurs, pelvises, skulls and scapulae. When a collection of smaller scavengers such as foxes, fishers, skunks, bobcats, eagles and vultures feed on a deer carcass the majority of the bones and skeleton will remain intact, picked clean of meat. With just this basic knowledge in mind, examine the photos below of a deer carcass in northwestern Oregon, taken by Paul Glasser, and try to determine what has been feeding on it.

|

|

|---|---|

|

Photos by Paul C. Glasser

|

|

Notice that the posterior ribs have been chewed through, and some of them have been pried and bent out to odd angles. The hind legs have been picked clean, and the femurs, fibula and tibia are still articulated to the skeleton. The heart and lungs of the deer are uneaten, but the fleshy exterior of the rumen has been consumed almost entirely, leaving its inner contents exposed. The front right leg of the deer is entirely missing, but given that the articulation of the scapula to the ribs and vertebra is entirely muscular and not skeletal this is not surprising. Finally, the carcass has been left in the middle of the creek and the position of the animal is consistent with a natural dying pose, indicating that the carcass has not been drug or repositioned. All of the above are great indicators of the feeding of mesocarnivores such as foxes, bobcats, fishers, raccoons, skunks, etc., and are negative indicators of larger predators such as black bears, mountain lions, wolves and coyotes. This buck was hit by a car on a road nearby and limped off to die in this creek bed, and Paul placed a trail camera at the site after taking the above photos, which revealed first a bobcat and then a coyote feeding on the carcass. Let’s break this story down by the various body parts and organs of the deer and the feeding sign that they bear.

Digestive Organs: Bobcats and mountain lions are obligate carnivores, and both species tend to leave the digestive tracts of their herbivorous prey completely untouched, and sometimes they even remove these organs and cover them with debris a short distance away from the rest of the carcass. In the case above, the fact that the digestive organs have been opened and fed on suggests that some other omnivorous scavenger was at work before Paul”s camera captured the bobcat. Bears, coyotes and most omnivorous mesocarnivores will eat at least part of the rumen or intestines, and sometimes they will eat the entire tract and its semi-digested contents. Benjamin Kilham has observed black bears feeding directly on deer scat and speculates in his excellent book, “Among the Bears”, that this serves to inoculate their own guts with the bacteria upon which deer rely to digest plant matter, thereby increasing their own ability to educe nutritive energy from vegetation. It is possible that bears and omnivorous mesocarnivores derive a similar benefit from feeding directly on the stomach and intestines of ruminants. In short, bobcats, mountain lions and other obligate carnivores are very careful not to make a mess of the digestive tract and its contents, while more omnivorous species tend to show indifference and sometimes the opposite inclination.

Internal Organs (heart, liver, lung, kidney):

Placement, caching, and tidiness: Different species of carnivores have different preferences for where and how to feed on carcasses, and they also differ in their ability to move and cache them. While a black bear may be able to entirely bury an elk carcass in vegetation and forest duff this task would surely be insurmountable for a gray fox, who may instead resort to removing individual chunks of meat to be cached separately nearby. And while a grizzly bear may choose to drag an elk carcass a few hundred yards to a more secluded place to feed, a mountain lion (or any smaller critter for that matter) would be unable to move such a large carcass and would be forced to feed on it where it died. Animals also have different morphology that makes them more or less willing or able to navigate certain types of terrain while dragging a carcass, and in some cases, it is possible to identify a predator just by the seeing the path where the carcass was dragged.

Hiding refers to the overall placement of the carcass on the landscape, which mountain lions are quite particular about. If the carcass is small enough for them to move (anything deer-sized or smaller) than they will almost always drag it to a sheltered place to feed. Mountain lions generally like to feed under some sort of cover if available, which can be a rock overhang, a willow thicket, or a stand of dense young firs. This behavior serves at least 3 purposes: 1) reduces the visible detectability of the carcass, 2) provides shade which minimizes spoilage of the meat and thereby reduces the olfactory detectability of the carcass, and 3) provides the mountain lion with shelter from the elements as it feeds. How far a mountain lion will drag a kill depends on the terrain, how near the closest suitable cover is, and how large the kill is. For adult deer kills in the mountains of the Pacific Northwest somewhere between 40 and 150 yards seems normal, although I have seen instances where lions carried prey much farther. Lions tend to drag their kills downhill, and it is common for them to end up in the bottom of a drainage or right next to a creek.

|

|

|---|---|

|

Left: Drag mark where a female lion drug a buck downhill to a secluded feeding site in the brush in the background of the frame. Right: The buck from the left picture after the kill had been kleptoparasitized by a black bear, and drug out of the lion’s secluded feeding site and left out in the open. Note the drag mark leading backwards from the buck and up to the top right corner of the frame.

|

|

Black bears will often drag a kill from where they discover it as well, but where they drag them to often lacks the strategic purpose that appears in mountain lion drags. Bears will often drag a carcass a hundred yards or more just to leave it completely exposed in the full sun, a behavior which is inexplicable to me. Bears tend to drag large carcasses in a direct line, choosing to go over or break through obstacles such as fences or thickets, whereas mountain lions tend to go around these barriers. Large black bears are much more powerful than mountain lions, and they are capable of dragging larger carcasses over fences or bending and breaking strong wire fences, while mountain lions tend to drag large carcasses right up to a fence and feed on it from the other side, through the fence, rather than attempt to drag the carcass over the fence. Bears also feed in a semi-haphazard way, tearing away at whatever part of the deer is most accessible, and this can result in carcass that are mutilated in very asymmetrical, random seeming ways. I think this speaks to the fact that for a bear a deer carcass is a very occasional bonanza, something that happens so irregularly that perhaps they don’t have the opportunity to develop a methodical order of feeding, whereas for mountain lions deer carcasses are their bread and butter, and everything about the way they feed on them is designed for efficiency and discreteness. When bears feed on deer for several days it is common for the kill to end up partially spread around, with a few bits of hide, bone and fur left over in various beds they’ve used while feeding. In these cases, it is common to find a mostly intact spinal column, sometimes with the pelvis still articulated, with a scapula or two and skull elsewhere but nearby. When coyotes and wolves feed on ungulate carcasses the result is typically quite a yard-sale, as the carcass is scattered about by the individual pack members who each retreat to his/her own preferred corner to feed. Compared to all other North America predators mountain lions are exceptionally tidy with their kills, although this excludes bobcats and lynx whose feeding habits are similar but lack the tendency/ability to break large bones as mentioned previously.

|

|

|---|---|

|

Left: A lion kill stolen by a black bear who drug the kill out from the lion’s cache to leave it in the full sun on a summer day. Note the atypical feeding pattern which resulted in the deer being torn in half. Right: a buck killed by a lion but mostly fed on by a bear. Note how the meat has been pulled and shredded off the ribs but the ribs have not been eaten themselves – lions always feed by eating the rib bones and meat simultaneously.

|

|

Caching is the term used when animals hide their food in one way or another. The term applies equally to Clark’s Nutcrackers stashing pinyon pine seeds and to grizzly bears burying a moose carcass. Mountain lions cache deer and other kills by piling forest duff and debris on top of them. There is no digging or true burying involved, and while some dirt may end up in the mound atop the carcass the mountain lion’s caching behavior is mostly restricted to the layer of forest detritus above the dirt. Moss, twigs, grass and dead leaves can all be used by mountain lions to cover a carcass, which are swept up by repeated, careful strokes of the front paws in slow rotation until the carcass is covered from all angles. Mountain lions do not always cache their kills, and the behavior appears to be much more prevalent in areas where mountain lions experience high levels of kleptoparasitism. Before caching a kill, a mountain lion will usually fold the carcass into a neat little bundle, which minimizes the amount of meat that will be exposed to dirt. This is one of the key differences between caches made by mountain lions and those made by black bears, who also mound debris atop carcasses to minimize detection by other carnivores. When bears cache a carcass, it is common for lots of dirt and debris to enter the carcass (in the abdominal and thoracic cavities) and for exposed meat to get coated in dirt. I have found many deer carcasses where the deer was stuffed with dirt like a thanksgiving turkey, which is a result of the comparatively careless fashion in which bears cache. Mountain lions are apparently very careful to keep dirt and other unwanted spoilage factors from contaminating the meat, and their kills are kept very tidy. In addition to the amount of dirt packed into the carcass and on the meat, another useful clue for distinguishing bear and lion caches is the general amount of material used. Mountain lions tend to use just enough material to get the job done, whereas black bears often go way overboard and create an unnecessarily gigantic mound of debris.

Additionally, any carcass being fed on by a black bear is going to be surrounded with associated black bear sign – tracks, scats, stomp-marking trails, rub-marked trees and distinct bear beds. Being generally familiar with all of these signs is very helpful in interpreting kill-sites, but is beyond the scope of this article. Bear beds however are worth mentioning here because they often bed literally right on top of the cache mound, giving a distinct appearance to the cache. Black bears create very deep beds, hollowed into the ground by repeated rubbing, rolling and pawing, and leaving a distinct circular impression right next to or on top of the cached carcass.

As a safety note, black bears can be very defensive of carcasses and some individuals are likely to bluff-charge if you attempt to displace them from the kill, and some may even attack. Mountain lions however are almost never defensive of kills when humans approach, but in any case it is extremely important to be very aware of your surroundings when at a kill-site, especially if there is sign of a bear around.

Latrines are what we call repeated defecation sites used by an animal. Raccoons create latrines at the base of trees in which they sleep, and mountain lions create latrines at kill-sites where they repeatedly gorge themselves. It is largely a misconception that our North American wild felids cover their scats, which is more typical behavior of domestic cats, but the one place where mountain lions do cover their scats is at their kills. I believe the function of this behavior is purely to minimize the olfactory detectability of the kill-site, and several times I have seen where a mountain lion has elected to poop in a stream over and over again as it fed on it’s kill nearby, rather than create a typical latrine. The water serves to keep the scent down just as well as forest duff, and requires none of the work! Mountain lion latrines are just piles of duff which are about 18 to 24 inches in diameter and 8 to 16 inches high which contain anywhere from 1 to 5 scats. Sometimes a lion will choose to make a new small latrine pile every time it poops at a kill-site and sometimes they choose to continue adding to one latrine. Regardless, this is a uniquely mountain lion behavior and is diagnostic. Black bears, having taken over a lion’s kill, will open up the latrine and eat the lion scats inside, much as some domestic dogs are attracted to domestic cat scat (much to the dismay of their owners). Black bears scat next to their beds and wherever they spend time and make no effort to cover their scats.

Kleptoparasitism is a routine part of the mountain lion’s existence, and in some regions they lose the vast majority of their kills to dominant scavengers such as black bears, wolves, grizzlies and even condors. Where I work in Humboldt County, CA, we have one of the highest black bear densities in the world. This results in mountain lions having almost every single one of their deer kills stolen between the months of April and December when bears are most active. This makes a more complex task for researchers, farmers, wildlife managers and outdoor enthusiasts hoping to interpret ungulate kill-sites. Confirming that a mountain lion killed an animal after a black bear has been feeding on it for several days can be extremely difficult and sometimes impossible, but there are several important things to look for and those are killing wounds, plucked hair, old caches and old latrines.

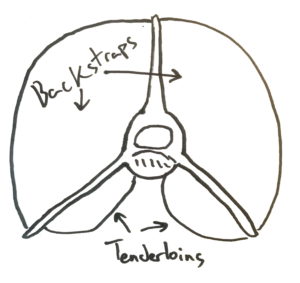

Killing wounds are where the mountain lion used its powerful jaws and canine teeth to kill the animal. This is usually accomplished on ungulates by biting the throat and crushing the larynx, which asphyxiates the animal. On smaller deer like yearlings and fawns mountain lions may simply crush the back of the skull with a powerful bite, but the skull of older animals and those with antlers is often too tough and bony to allow this. Mountain lions also sometimes bite the noses of ungulates as they battle to subdue them, and this can result in distinctive teeth and claw wounds. One very effective way to identify whether or not a mountain lion killed an animal is to open up the skin of the throat with a knife and examine the inside of the skin for puncture wounds and clotted blood, which results from wounds that bleed internally while the animal is still alive. Occasionally you will find puncture wounds that are clear enough to identify the two upper and two lower canine marks of the predator, and measuring these with calipers or a ruler can be helpful. The distance from the tip of one upper canine to the other on a mountain lion is usually between 1.6″ and 1.75″, and about 1.5″ between the lower canines. Black bears are usually 1.8″ to 2″ between both the upper and lower canines, but some smaller bears may overlap with larger lions, but black bears typically attack animals from the back of the head and neck. Additionally, it is exceedingly rare for a black bear to be able to capture a healthy adult deer (although they decimate fawns in the early summer) so almost any kill you find with a bear on it was probably stolen. If there is clotted blood and canine wounds in the throat of the animal, it was almost certainly killed by a lion or bobcat (bobcats kill deer too, but again, can’t crunch large bones).

|

|

|---|---|

|

Left: I accidentally discovered this kill when I heard the bear caching the carcass and went to investigate. Knowing that bears are mostly unable to capture adult deer I suspected it had been killed by a lion so I skinned out the neck to confirm. Sure enough, puncture wounds and clotted blood (pictured right) pooled on the underside of the neck tell that this animal was killed by asphyxiation – the typical kill method of mountain lions.

|

|

Plucked hair may be the only way to tell the original predator of a kill if a bear has been feeding on the carcass for a long time and has destroyed most of the other evidence such as neck wounds. As mentioned earlier, before eating any part of an ungulates body the mountain lion will meticulously pluck the hair, one mouthful after another, leaving a large pile of distinctively clumped fur. If you have a kill-site with bear sign everywhere and only little bits and pieces of bone remaining, take a walk around and look in the sheltered shady nooks nearby for piles of plucked fur – this will tell you without a doubt that the kill was originally made either by a mountain lion or a bobcat. Again, if the kill is fresher the way to distinguish bobcat from lion kills is by the thoroughness of the cache and the state of the large bones – half-cached with all large bones intact? Bobcat. Fully cached with large bones crunched? Mountain lion. Old caches and old latrines may not survive the antics of a feeding bear but often enough they do and can provide definitive evidence of mountain lion feeding. If there is a drag mark leading backwards from the carcass, follow it as far as you can and you might find where the lion originally removed the digestive organs and cached them, or where it plucked hair from the flank. If that does not work look for latrines which may or may not have been opened up and fed on by the bear.

Mesocarnivores & Small Prey

When mountain lions feed on mesocarnivores and other small prey such as rabbits or small domestic animals, the feeding sign can be quite different from large ungulate kills, but several of the rules outlined above remain true. Mountain lions still pluck at least some of the hair from small kills, though the smaller the prey item the less hair is plucked. Very small animals such as chipmunks, mice, warblers, voles and woodrats may be eaten in their entirety, making interpretation of the sign and confirmation of predation difficult or impossible. For medium-sized critters however, such as foxes, raccoons, fishers and house cats there is a typical appearance to the sign left by feeding mountain lions, where the tail, digestive organs, and fragments of the skull remain. Mountain lions are generally not keen on eating tails, which promise a mouthful of hair and bone and not much meat, so these are typically found almost completely intact, and it is unusual for a lion to consume any more than the proximal 1/3 of the tail which has more meat. And just as is the case with larger prey such as deer, the bonier parts of the skull including the supraoccipital plate and the palate with rows of molars are ignored. However, when feeding on deer kills mountain lions often feed on the nose, crunching off the distal ends of the nasal, premaxillae and turbinate bones, but these parts are ignored on mesocarnivores. In fact, on mesocarnivores killed by mountain lions it is common to find the entire snout and nose left perfectly intact, with the skull crunched and eaten from the orbits backwards. Bobcats however are typically either incapable or uninclined to actually crush the brain case of even small mesocarnivore prey such as mink, and instead with their kills you tend to find intact skulls with canine puncture marks in the brain case. It is very unusual to find intact mesocarnivore skulls at mountain lion kill-sites, and this can be a helpful way to differentiate their kills from those of smaller carnivores. Both mountain lions and bobcats leave the digestive organs of mesocarnivore prey intact in a neat pile, but other carnivores such as coyotes, wolves and domestic dogs may or may not eat these organs.

|

|

|---|---|

|

Left: Two American mink skulls, both of whom were killed and fed on by a bobcat. Right: a northern raccoon skull which was killed and fed on by a mountain lion. Notice that the mink skulls are both completely intact, and that the left skull bears canine puncture marks while the right skull is completely unbroken, while the much larger raccoon skull was largely destroyed by the feeding mountain lion.

|

|

Smaller prey such as gray foxes, fishers and rabbits are typically too small too warrant caching by a mountain lion (indicating that the lion was able to completely consume the animal in one sitting), but larger animals such as coyotes, beavers, and large raccoons and bobcats are often cached. The raccoon in the image above was not cached, and the female mountain lion who ate it spent 14 hours at this location, and most of that time was likely spent napping rather than feeding. Interpreting smaller prey kill-sites can be more challenging because the predator spent less time consuming the animal, which results in less accumulated sign for you to read, but the key features of mountain lion kills on mesocarnivores are 1) Skeleton almost entirely consumed, 2) Skull crunched, and 3) Digestive organs intact.

Putting it All Together – A Real-World Scenario

Now let’s walk together through a real-world example of livestock depredation that I was called to investigate, and use the information we’ve learned to try to come to a definitive conclusion about which predator was responsible. So in this scenario you have been called out to investigate where a goat has been killed. The goat’s owner actually watched this happen in the middle of the night, and informs you that they are 100% certain that the goat was killed by a mountain lion. Immediately you notice where the 4 foot-tall welded-wire fence has been mangled and bent over, and blood and hair are stuck to the fence. Right beyond the mangled fence is a blackberry thicket and the white undersides of flattened and overturned leaflets clearly show where the carcass was dragged.

But at this point we have not ruled out with 100% certainty the possibility that a mountain lion killed the goat, only to have it very quickly taken by a black bear. To come to a certain conclusion you search the area thoroughly for any piles of plucked hair, and examine the chest of the goat to see if any hairs have been plucked. Finding none, you examine the fine dust in the pen of the goat very closely, looking for any partial mountain lion tracks. Even finding one mountain lion track in the pen would place a lion at the scene and with that evidence plus the testimony of the owner you could be certain that a mountain lion had indeed killed the goat. But instead you find only black bear tracks in the pen, and in combination with the mountain of evidence of black bear predation and the complete lack of mountain lion sign we are now certain – a black bear killed this goat in the pen, and drug it over the fence and the blackberries and fed on it. Now, if the owner of the goat is interested, you should respectfully communicate and show them the evidence you are seeing and explain why you have come to the conclusion that you have. Many people are quite upset after losing an animal to a predator, and having someone come in and tell them that the mountain lion they saw was actually a bear can trigger emotional reactions, so it is important to be compassionate and respectful when explaining yourself.

Finally, sometimes it is impossible to be certain just what happened to an animal, even for experts with decades of experience. But it is just as important to recognize when that is the case, and to maintain a professional attitude and be honest with your employer, the public and yourself about when the situation is just not clear enough to interpret. In this modern age traditional field skills like tracking and kill-site interpretation too often take a backseat role to advanced models and statistical analysis, but your model is only as good as the data you feed it, and your data is only as good as your interpretation of the sign. Honesty is of the utmost importance. Afterall, some day it might be an animal’s life on the line if you make the wrong interpretation. Stay curious, stay engaged, and stay outdoors!

Phil Johnston is a professional wildlife tracker, photographer, nature writer, outdoor educator and musician. He lives in Humboldt County in far Northern California where he works for the Hoopa Valley Tribe as the Mountain Lion Biologist. Visit

Phil Johnston is a professional wildlife tracker, photographer, nature writer, outdoor educator and musician. He lives in Humboldt County in far Northern California where he works for the Hoopa Valley Tribe as the Mountain Lion Biologist. Visit

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email