Gary Koehler on Applying Science to Attitudes

An Audio Interview with Julie West, MLF Broadcaster

Listen Now!

Listen Now!

Listen to the interview from MLF’s ON AIR program, podcasting research and policy discussions about the issues that face the American lion.

Transcript of Interview

Julie: Hello. I’m Julie West, your host. Thank you for listening to On Air with the Mountain Lion Foundation. My guest today is Gary Koehler, wildlife research scientist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife from 1994 to June 2011.

Gary’s expertise includes thirty years of research on a variety of carnivores including the cougar, black bear, Canada lynx and snowshoe hare. He continues to participate in cougar and lynx research in Washington and advise projects concerning tigers in China and snow leopards in Mongolia.

For the past eight years, Gary’s been involved in Project Cat, a community outreach program that engages public school children, teachers, and the community with hands-on environmental educational opportunities in science fieldwork. Prior to his affiliation with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Gary served as former research associate with the Hornocker Wildlife Institute and senior lecturer at Moi University in Kenya. Additional biographical information for Gary is available on the Mountain Lion Foundation web site. Hello, Gary.

Gary: Hi Julie. Good to speak to you.

Julie: Thank you so much for being with us today. I want to start by observing when there are increased news reports of cougar conflicts with humans or cougar livestock and pet encounters, it seems the common assumption is that, “Oh, cougar populations must be growing,” and people can really panic about this. You know, “Get your guns out, aaahhh!”

But your research suggests that there’s more to the story than meets the eye and that this is actually maybe a misnomer, that poorly designed hunting policies might be triggering this increase. What are you finding, and how can you address this public perception?

Gary: Julie, in Washington State we’ve studied cougars here over a decade, and we’ve looked at cougar populations in five different areas; very distinct ecotypes in the state. What we’ve done in this long term research was really unique and instrumental in unraveling some of the mysteries about their populations and how they respond to hunting.

What we found in one area where we had studied cougars and where the community participated in this process called Project Cat, Cougars and Teaching, the area received a relatively low harvest rate of about 10 percent per year.

The cougars, like elsewhere in the west, can live in close proximity to people; particularly in developed areas. In fact, that’s what they did there, and there were very few people complaining about cougars.

That low harvest rate resulted in an older-age population, and the animals there were able to go about their lives, regulate their own numbers the way they evolved with the territoriality and dispersal of young male cougars that were born in the area.

Then we looked at cougar populations in the northeast part of the state where the harvest rate was more than double that. It averaged about 20-23 percent per year. As a result of that, this resulted in a quick turn over of the population. The average age of the cats there were about half that of the other areas with low harvest, the Project Cat study area.

The average age was about three years old where the cougars were harvested intensively, in contrast to six to seven years old where there was that lower harvest rate.

As a result of that, when you continue high pressure like that, you’re creating these territorial vacancies. You’re creating an opportunity or a vacancy where young dispersal-age cats, inexperienced cats, are going to have an opportunity to find a vacancy and set up their own territory.

Also what happened there, the high harvest really disrupted the social organization, particularly for the males. Rather than being exclusively territorial and having exclusive areas and parsing out the landscape, these young-age cougars, their home range areas were much larger than in the control where the harvest rate was low and like two to three times as large.

The males were basically stacked upon each other. So there’s increased opportunity for — if you live on a site in the northeast part of the state — you could be visited by three different resident or establishing cougars, male cougars. (Where if you have an area where the harvest rate is low, that would be the domain, and your area might be the domain of one male cougar.) So the probability of encounters basically goes up.

Also the cats are inexperienced hunters. They haven’t had the experience of living around people. They’re kind of like juvenile, inexperienced people or a variety of other mammals including ourselves.

Julie: Teenagers, my teenagers (laugh.)

Gary: True. The inexperience, plus higher probabilities of encounters with people, leads to a potential for increased conflict and increased complaints.

Julie: So the key really does hinge then on, it seems like, if I am understanding you correctly, the heavy hunting is taking out the older males and the population structure is shifting. You have these younger juvenile cats who need to establish their own territory, so they’re more likely to come onto conflict without the dominant male cat kind of keeping that social order intact.

Gary: That’s correct. That’s exactly what we found. This was a unique study, and we were able to compare two different study areas with basically two different harvest intensities, and that’s exactly what we discovered.

Julie: When your data is this compelling, and that’s not to imply it’s not without controversy because I’m sure it is and that people are interpreting this in a number of ways. Maybe you could address that in a minute. But how can you, then, affect policy or what’s the next tier? Where do you take this data? Where does it go from there?

the high harvest really disrupted the social organization, particularly for the males

Gary: Here in Washington State we are attempting to affect policy. We’re trying to take this science and this understanding that we’ve found and to attempt to minimize or lower the harvest in any one particular area.

What you create is an unregulated harvest structure or an area where access is easy in the winter time. Hunters can get in where there’s lots of roads, and if you have snow, cougars are particularly vulnerable. In these areas you can create conditions for a high harvest rate or a high hunting mortality, in an area with high roads and good snow conditions.

You can create a situation just like what we explained and that population is going to be dominated by these young inexperienced cats coming in and taking over vacant areas that were once occupied by older-age resident male cougars. What we’re trying to do is distribute the harvest or distribute the hunt effort on the landscape where hunters don’t necessarily go, where the picking’s easiest, where the road density is high and where you’ve got good snow conditions because cougars can be quite vulnerable under those conditions.

Julie: So you’re saying that maybe state agencies like the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife can dictate those parameters, can have a say in where those locations should be, and offer the cats to the hunters, but maybe not make them such easy targets.

Gary: That’s correct. Basically distribute the hunter harvest over a wide area so the hunters are not necessarily attracted to the areas where it’s easiest to get a cat. I know everybody wants to be successful, but if you’ve got areas with high road density and good snow conditions, you can seriously impact a cat and cougar population with the result of a whole change in the population structure and potential complaints going up.

Julie: Does that necessarily assuage fear? You still have public perception to deal with. How is that piece of it addressed?

Gary: Well, what we’re trying to do, and this is true with a lot of agencies in the west, as well as private entities like The Cougar Fund and The Mountain Lion Foundation, is educating the public, and that’s a very important part of all of this. Agencies are trying to step up and play that role as well. It would appear, at first hand, if there’s more cougars being seen, that one would think, “Oh, there’s got to be more cougars out there,” but it may not necessarily indicate that.

I saw a cougar just the other day on a hike here in the snow. Obviously it was a young cat, and cats are curious. And the old adage, “curiosity killed the cat,” you know young cats are vulnerable &mdash young cats are curious &mdash and very often that’s what you see is younger-aged animals. It’s not necessarily an increase in populations.

In fact, cougars are very good with their territorial makeup of their population, spacing themselves out on the landscape so that they don’t overwhelm the prey population. There’s a limit to the number of cougars that you can have on the landscape.

Julie: Is it possible for the cougars, if you were to greatly back off on the hunting or greatly change the hunting regulation to give them a break, is it possible it could go the other way?

Gary: No, I don’t think that there’s a danger of cougars getting out of control. I think there’s a good example of that in California where there hasn’t been any harvest, or public harvest of cougars. You don’t get reports of cougars overwhelming the landscapes in California.

Julie: It does seem like so many things are stacked against them, with highways and development and loss of habitat, that those would be built-in ways of limiting their numbers already.

Gary: Basically what dictates cougar numbers is habitat, and definitely is prey numbers. So if you’re going to lose habitat, you’re going to lose prey: elk and deer, and that’s going to impact cougar populations.

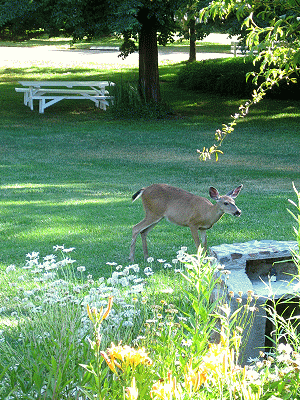

So that is an area that it is not only loss of habitat through development, but that impact can be magnified by enticing deer into residential areas and have an impact on the cougar population by attracting the cougars into these residential areas.

Julie: And where does trophy hunting figure into this? For me, I think of trophy hunting as being in a unique category outside of hunting. But maybe it all stems from the same desire to — not always — but to sort of conquer and literally take the trophy from nature. That’s a major contributor of decline in cougar populations, isn’t it?

Gary: Well, it can be in some areas. I mean cougars are a highly prized game species. There’s few people that kill them for food, but they like to have them as a trophy animal. I think there is a certain amount of off-take, if you want to put it that way, or hunting that you can permit in an area. But the older toms, they’re larger and they’re bulkier. They’re much more valued trophies than a young-age cat or a female. They’re just bigger, maybe twice the size of a female in weight, so they’re the valued trophy.

But the thing of it is, when you’re taking those trophy-aged animals, those older males, you have the potential to create a population sink if you kill a lot of these large older males in an area. You’re killing off the older resident toms that have well established territories, and kind of dictating the demographics in the culture and the policy of cougar behavior. Those older-age animals, those trophy-age animals are a very important part of the population. They help regulate the numbers. They help force young-age animals to disperse, and they basically regulate the numbers of cougars on the landscape through territoriality. So they have a very important role in the natural scheme of things.

Julie: It should make sense. Elders in our own human societies have played such a critical role in maintaining order and stability and passing on the traditional wisdom and knowledge. Why wouldn’t it be so for the animal world as well?

Gary: It’s definitely true. That has been documented very clearly in elephants, documented very clearly in a lot of our primary species in Africa and Asia, and a lot of our ungulate populations too. They’re matriarchal. The older cows pass on to the younger calves travel routes. There is culture in these animals, and these older animals do play a very important role in not only seeking out and showing the younger generations where to go, but in the case of cougars, regulating the numbers of cougars on the landscape in territoriality.

You’re killing off the older resident toms that have well established territories, and kind of dictating the demographics in the culture and the policy of cougar behavior.

Julie: So how can the Department of Fish and Wildlife communicate to hunters, or what is an ideal goal in communicating to the hunters? You suggested one strategy of not making it so terribly convenient to get to the cats, number one. But how can someone resist taking out a big cat if that’s their goal. If, as you say in trophy hunting, the bigger the cat the better, knowing that that bigger cat is likely going to be one of those older, mature elders who are needed, can you limit the number of older male cats you can take out?

Gary: I think that’s kind of the key is limiting the number of older cats that are harvested in the area. Basically putting a limit or a quota on the number of cats that are harvested on a particular drainage, particular game management unit, or population management unit, whatever the management designation for the area might be. Limit the number of animals harvested in a particular area.

I think a corollary to that is rather than create situations where cougars are very more vulnerable because of good road access, if you can distribute the hunt throughout the region, throughout the state, so you’re not taking out all of those older animals out of a particular watershed.

But if you take out all the toms in this area, then what you’re going to do is basically create a social chaos in there and a potential for turmoil as we discovered in the northeastern part of the state where we studied cougars.

Julie: What you propose is so reasonable and logical in my way of thinking. What could the resistance to that possibly be?

Gary: I think some of the resistance is, with most state agencies, wildlife management agencies; we still have this idea ingrained in our psyche that cougars are indeed predators. They don’t require any special management needs or, “Let’s just harvest them but not worry about it. I mean they’re going to reproduce.”

I think what we’re trying to deal with here, and what we’ve got to convince our own agencies is that, “Hey, there’s a better way to manage these large predators,” particularly cougars and that the evolution of the cat is all a part of this. We need to be aware of that behavior in this territoriality of these cats is a unique thing about cougars — not necessarily unique about cougars, but it is certainly characteristic of all of the cats — and that we should be aware of this when we’re setting up a management strategy.

Julie: It seems to me that these agencies such as your own Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife that you were affiliated with for so many years, they are working with research scientists such as yourself. They do have the benefit of this incredible biological knowledge just by association of their partnership and their own team members, so it must have been very challenging, but also hopefully rewarding, for you to work within that system and to find that maybe their policies didn’t always agree with you, but also to find that maybe you could help effect change from within that system

Gary: Well, we are trying, and we’ve done that. We’ve put a lot of effort in it. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife did sponsor most all of this research, or helped sponsor most of the research that we’ve done in this state, as have the universities here: both WSU, Washington State University, and the University of Washington has been involved as well.

So they are receptive, but there’s still this notion in some management people and personal that predators are different. They’re just considered something different: vermin.

It’s a real challenge to try to change perceptions of carnivore — large carnivore — management. We so often considered them as predators, but we are making inroads. There are changes, but we also have to pass regulations and get the approval of wildlife commissions.

We have wildlife commissions here in this state and elsewhere. Other states have them too. That is where the hunting public has a voice, and they’re often reluctant to make some of these changes because they don’t want their opportunities compromised. We need to start applying the science of the ecology of these animals to our management.

Julie: Were you ever in a situation, at conferences maybe, where you could really get down into some serious debates with fellow game and fish colleagues?

Gary: Yeah, we did. Every three years, or something, agencies and non-governmental agencies have a program called The Mountain Lion Workshops. There all of the agencies, state agencies, convene, and you have great opportunities to talk about that.

We’ve in fact presented some of our ideas to the last Mountain Lion Workshop and that was this spring. They’re aware of what we’ve done. They’re aware of what can be done to better manage things. We do have dialogs with an exchange of ideas with other agencies, state agencies, and we have discussed this. There’s getting to be a greater receptivity to some of these ideas but it’s like any change, it takes a while. You just have to be persistent and really present a convincing argument.

Julie: The argument might not need to be so convincing for your fellow game and fish colleagues perhaps, but it seems that the greater challenge would be their community, their community of hunters.

Maybe this idea that academia, the scientific knowledge coming from the ivory tower of academia, doesn’t really relate to the average person who just wants to have his gun and have free reign and go wherever he wants to and, “Why should a scientist at a university coming up with data tell me what to do?” Do you think that those are just some real basic challenges?

Gary: There are those challenges, but we have those same challenges within our own department. Just as there are different philosophies within the hunting community, there are some hunters that are really receptive to these ideas we’re talking about.

Julie: That’s a good point. Thank you for mentioning that.

Gary: Within agencies there’s some of the kind of the “good old boy” attitudes too that are tough to change. But the thing of it is where we’re trying to get in this state and has been demonstrated elsewhere, particularly in California, is the role of science in unraveling some of the mysteries of this animal and trying to implement some of these findings in the management.

We’ve got our own people to convince. There’s a lot of positive movement. I think we’re all on the right track, and we’ve got the momentum. But it’s not smooth sailing, either with the management agencies or the hunting communities. But there are people that get the picture, and they understand the need to make some changes.

Julie: I was just reading a story in the news recently, I’m sure you know about it, of a hunter in Washington State who shot and killed a mother cougar and consequently orphaned her three kittens. The thing is the hunter said he knew it was illegal to shoot the mother. He was aware of her kittens, but he shot her anyway.

It just seems that despite reason and the best efforts of yourself and others who are working toward achieving this balanced human/wildlife dynamics, there will always be examples of this blatant disregard for the law and that you’re really up against some deeply rooted entitlements to take at any costs.

That’s frustrating, but I like looking to your work of Project Cat and young people as being the hope to the restorative justice side of that. Maybe you can tell us a little bit about how that’s going and how you’re empowering people with this knowledge.

Gary: I think Project Cat was an experiment, but I think a very successful project. What I’ve learned more than anything is, really, the way to change attitudes within the community is through the kids in the schools, where we had with Project Cat we involved, anybody from 8th graders and older. We took them out on these captures, and they followed us around the woods to capture animals. That knowledge that they gained and acquired from working with us…

Julie: Capturing them for the purpose of radio collaring them?

Gary: Radio collaring them, and studying them, and finding out what their relationship is on the landscape and how many animals, and what their predation ecology was, and relationships with their use of space with where people live.

These kids have a first hand view and a first hand understanding of all of that because they got to work there. They took that understanding home. They talked about it with their extended family at thanksgiving dinners. In fact, it was a lot of these kids that made the greatest impact into that community, telling their grandparents not to feed the deer because it’s going to attract predators.

It was the kids that were the champions. They were the ambassadors in the community and had the most affect on changing attitudes about cougar ecology. I think when we left there, that community was certainly supportive of Project Cat. Everybody in the community was deeply involved in it and really understood much better the role of the cougar in their neighborhood and as part of their neighborhood. So it was the kids and education through the schools and getting the kids involved that made a difference in that community.

Julie: Seems like we need a network of Project Cat programs across not only Washington but the northwest and the southwest too.

Gary: Yes, on a variety of topics. Cougars are one of them and cougars are very important because they hold such … they’re such a beautiful animal but we still fear them. Just unlocking that mystery about the lives of cougars in that community and having the kids take that home really did make a big change in that community

Julie: Very important work. Well, we’re running out of time, but I do want to ask how your knowledge of big cats in wildlife management here in America is informing your research in countries such as Africa and China. Are there relations in your findings?

Gary: Actually there’s the old adage “a cat’s a cat,” and pretty much they are the most amazing and most sophisticated of the predators on our planet, most highly evolved.

Pretty much they just come in different disguises whether it’s a tiger or a mountain lion or a lynx or a bobcat. They have a lot of those same patterns. Those understandings of how snow leopards might relate to the villagers and depredation on villagers livestock is not a lot different than dealing with depredation issues here in the U.S. when it comes to cougars depredating on domestic goats or sheep or for that matter, wolves.

And I think that there’s a lot we can take home and apply elsewhere about the dynamics of predator communities and how we as humans live in these communities. So we pretty much take all of that information and transplant it elsewhere.

Julie: Maybe we could end with you sharing a story, if you’d like to, of one of your own encounters with a mountain lion.

Gary: It was just the other day my wife and I — this Saturday in fact — we decided we just had some fresh snow and we went for a hike up to these little lakes above Wenatchee and… sorry, the dog is barking. Here, I’m going to step outside.

Julie: You don’t have cats? (laugh)

Gary: No. I’ve got neighbor cats that seem to enjoy me, so we don’t need a cat here because we have cats all around us that come by.

But what is amazing to me is these cats, these cougars; they’re so secretive, they’re so stealthy. They can be close by you, and you would never see them there. You might see their tracks.

But like I said, Saturday on our hike out from these little lakes there was a movement off the side of the road as we were driving out, and my wife says, “I think that was a cougar.” So we stopped, and I got out. I looked over there, and sure enough, this young cougar stepped out. It was a young animal, just by its features, but it was not spotted so it was maybe a year and a half, two years of age.

That animal just stood there and watched us from not more than about thirty or forty yards away, and it was so awesome. I’ve spent 15 years of my professional career working with these things, and I never get tired of looking at them. They’re such an amazing and such a beautiful animal, and to be able to catch a glimpse, not to mention looking at one looking at us. It was truly amazing.

Julie: Yes. Well, thank you so much, Gary, for speaking with us today.

Gary: Well, it was my pleasure. Thank you very much for giving me the opportunity. These are fascinating animals, and I appreciate you letting the public know about the role of these amazing animals.

Julie: Well, thank you so much Gary. It’s been a great conversation.

Gary: Hey, thanks. Take care.

Julie: All right.

Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for noncommercial use.