By Paige Munson, Science and Policy Coordinator

Sharing a home with mountain lions

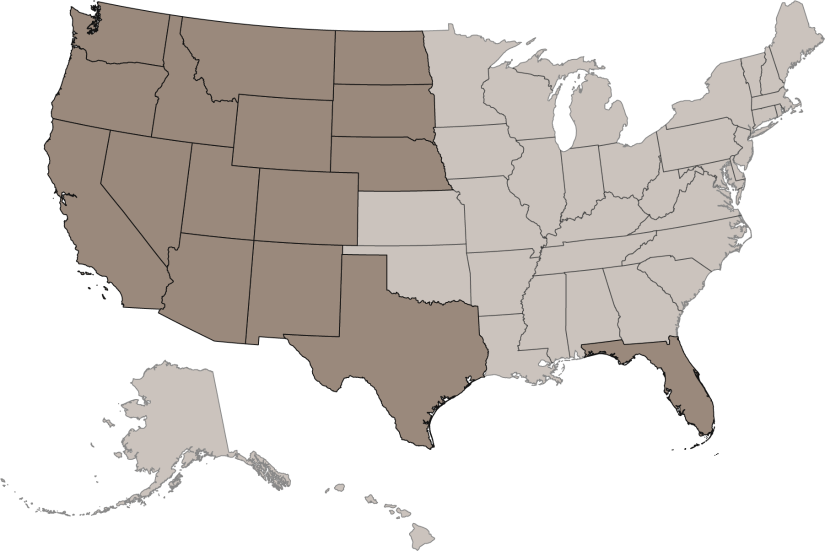

Colin Croft is a lifelong Nebraskan, naturalist, wildlife watcher, and teacher of ethics and philosophy at his community college. Ten years ago, he realized he was sharing his property with mountain lions. In 2014, Colin placed camera traps near his home in the Wildcat Hills. He was familiar with the wildlife in his area but was shocked to find images of a mountain lion on the camera. He kept his trail cameras active and continued to discover more about the hidden life of his community lions that live on what’s considered the eastern range of breeding lion populations in the United States.

Colin was thrilled to discover an animal that, most people assumed, no longer existed in Nebraska. His curiosity about the carnivore he’d seen on his camera prompted him to learn more about the cat, and inadvertently, about wildlife management in a state not known for lions.

Mountain lion management and the need for wildlife agency reform

“Mountain lions, to me, really opened up the world of wildlife management, “ said Colin. “When I was a young guy, I did a little bit of hunting, and a lot more fishing. I was familiar with our state parks and our state agency, but I never really thought about their role and what they did. It was through mountain lions that I understood the agency’s view on wildlife. I had never questioned it before. But there is this notion that the agency needs to focus on consumptive users, mainly the hook and bullet crowd, but also park users. But if you’re wanting to enjoy wild places and be a wildlife watcher, you’re excluded. I never really recognized that.”

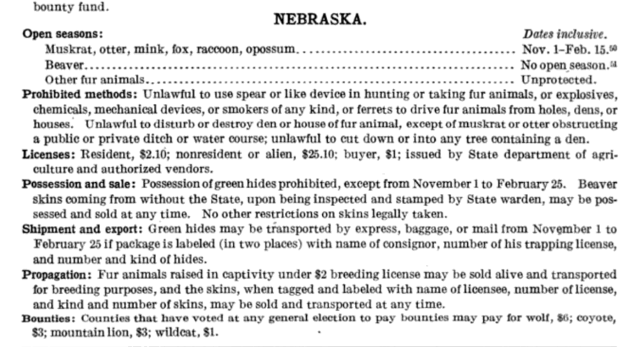

Colin also learned more about the historical attitudes of wildlife agencies towards carnivores. The last of the state’s mountain lions were mostly eradicated by the late 1800s. Part of this eradication was due to the overhunting of prey species but also to systematic bounties placed on carnivores with the goal of wiping them out. Colin says, “We’ve made a lot of ethical progress…and I believe there is hope for change. The history of how we view mountain lions and other species is proof of our change in perspective. We don’t need to look back very far to see that these were unwanted animals to most. I think mountain lions are kind of emblematic of our movement away from that.”

The first modern case of mountain lions returning to Nebraska was confirmed in 1991 in the Pine Ridge, an escarpment (steep slope) in the northwestern part of the state. In 1995, after a female mountain lion was shot and killed the legislature voted to list mountain lions as game animals. This status offers regulation to their hunting but can’t protect them from hunting itself. Nebraska Game and Parks has launched extensive radio-collaring programs and research, but most of this hasn’t been shared with the public nor submitted for peer review.

In 2014, the agency decided there were enough mountain lions to have a hunt, but the season has been canceled and reinstated more than once as the population numbers rise and fall. The agency’s latest population estimate for the Pine Ridge in 2021 was 33 mountain lions. No estimates have been determined for the Niobrara Valley or Wildcat Hills populations.

At Nebraska Game and Parks, the return of mountain lions to the state was seen as a success. However, “success” in this case only prompted the Agency to set population reduction goals after citing several complaints from landowners.

This logic didn’t make sense to Colin. He learned that mountain lions don’t overpopulate, making hunting unnecessary. He also learned that hunting won’t prevent conflict with humans. “It’s like trying to reduce crime by randomly imprisoning people.” Hunting doesn’t select for “problem” animals, so it is unlikely to solve for anything. Colin wants to see conflict with mountain lions dealt with on an individual level, with each case being treated uniquely, not a blanket assault on the species.

In addition to the Pine Ridge hunt, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission voted to approve hunting in the Niobrara Valley in 2023. In June of 2024 the Commission will be voting on whether to hunt mountain lions in Colin’s home, the Wildcat Hills.

Colin acknowledges that things could be a lot worse in Nebraska. “Some people don’t want any mountain lions in Nebraska, or an open season on them. The agency seems to be trying to find a middle ground.”

The case for more research by wildlife agencies

People like Colin who live on the eastern range of lion populations rely on information from states where there’s been more investment into learning about cougars. Colin says, “We rely on research from western states. When we’re thinking about Midwestern states [John] Laundre said we should really be calling them river lions. He makes the point that waterways are their transportation and infrastructure. If you have steeper elevations like in the western states, water goes from point A to point B pretty quickly. Since Nebraska is so flat, we have a lot of meandering waterways. It would really be valuable to have more research in Nebraska to see if mountain lions behave and recolonize differently than in western states. But whatever research we have going on here is done by [Nebraska Game and Parks] for its own purposes. The only time Nebraskans see the research is when it’s used to justify adding another mountain lion hunting season.”

Despite his frustrations with the lack of research investment by his wildlife agency, Colin still finds good in the department, including its support of the Master Naturalist program and their outreach efforts to educate more people about wildlife. Nebraska Game and Parks also puts efforts towards projects like the Nebraska Legacy Project that focuses on conservation. Colin has become a major voice advocating for reform at Nebraska Game and Parks through letters, hearings, petitions, and collaborative projects.

Outside of his work advocating for mountain lions in the Nebraska Game and Parks, Colin is an ambassador for the cougars in his own community. He hosts a Facebook page called “Nebraskans Living with Mountain Lions” to get people excited about the cats, shares his mountain lion images on iNaturalist for citizen science, and posts his mountain lion videos on his YouTube channel. He hopes sharing glimpses into the lives of lions will help people care about them as much as he does, and maybe to speak up for them too.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email