Genetic research indicates that the common ancestor of today’s Leopardus, Lynx, Puma, Prionailurus, and Felis lineages migrated across the Bering land bridge into the Americas approximately 8 to 8.5 million years ago.

What we know as a cougar today became recognizable as a distinct species about 400,000 years ago and inhabited nearly all of the Americas for hundreds of thousands of years, alongside the giant sloth, the mammoth, the dire wolf and the saber-toothed lion.

During the Pleistocene ice ages, conditions appear to have become too cold for cougar populations to survive, and paleontologists believe that at the end of the last ice age, the big cats repopulated North America from a southern refugium. Cougars have inhabited South Dakota, alongside humans, for more than 40,000 years.

Native Peoples

Native people memorialized the cougar in rock carvings, totems, in story and in song. As European settlement expanded in the 1840’s, cougar persecution and riding the landscape of dangerous wildlife became more common.

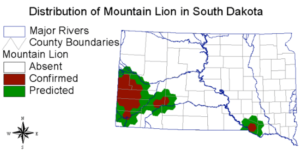

Mountain lions are native to South Dakota. They live primarily in the Black Hills, ideal habitat for lions, but they may occasionally travel through other parts of the state as they attempt to disperse and find territory.

Early people who lived in what is now South Dakota crossed the Bering land bridge that existed between Siberia and Alaska at least 17,000 years ago and were nomadic hunter-gatherers. They hunted large prehistoric mammals that lived in the region, including mammoths, sloths and camels.

The impact of early cultures on mountain lions was probably minor. Mountain lions were rarely hunted for meat. They were more often hunted in order to prove hunting prowess and to gain hunting strength as a warrior. Mountain lion skins were used for warm clothing and teeth, claws and paws were used for ceremonial purposes and to invoke strength for the hunt.

Native American tribes who have lived in South Dakota include the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Oglala Sioux, Arapaho and Mandan. The Cheyenne called the mountain lion ‘Nanose ‘hame’ and the Lakota Sioux knew the mountain lion as ‘Igmuwatogla.’

Black Elk was a well-known shaman of the Oglala Sioux who lived from 1863-1950 near Manderson, SD. Black Elk told much of the Oglala Sioux nation history to author John G. Neihardt, who wrote the famous book, Black Elk Speaks. Black Elk spoke of how respect for animals is a major part of Sioux culture and ‘two-legs’ and four-legs,’ including mountain lions, are seen as relatives.

The local tribes were hunters and crop-growers and became adept at trading with the fur traders when the first American fur trading post in South Dakota was established in 1817, Fort Pierre. At first, the Native Americans supplied the furs – from bison and beaver to wolves and mountain lions – and were able to trade for European commodities such as pots, pans and guns. As the fur traders learned where the wildlife was and how to trap and snare, they began to supply their own furs and were no longer as dependent on the Native Americans for local knowledge or for furs. The fur trade died out as wildlife began to disappear from the landscape, from over-trapping and from the spreading human settlement that drove the animals from their homelands in search of more remote and safer habitat.

There was a time when buffalo numbered between an estimated 65 to 70 million at their peak. Deb. R. Keim, a pioneer writer, observed, “I have seen herd after herd stretching over a distance of eighty miles, all tending in the same direction.” During that time other wildlife was thriving as well, including bear, bighorn sheep, wolves and mountain lions.

European Settlers

Settlers taking advantage of the Homestead Act of 1862 were lured to South Dakota with promises of abundant farmland and found a vast prairie that was harsh and unforgiving. Wood was scarce so settlers built homes from prairie sod that had earth roofs, dirt floors and prairie sod walls. While building up homesteads, many settlers had to find other work, such as hunting or mining, as most arrived with no money in hopes of a better life. As people attempted to build up their farms and ranches, mountain lions and buffalo could not compete with the disappearing range land and wasteful game hunting.

As the railroads came through the prairies, buffalo hunters, including Buffalo Bill Cody supplied meat for the railroad crews. The hunters took only the humps, tongues and hindquarters, leaving an estimated 3 million pounds of buffalo meat on the prairies to rot.

Homesteaders

From 1865 to 1900, homesteaders and sportsmen came to South Dakota and depleted what had seemed to be an unimaginable abundance of wildlife, from white-tailed deer to mountain lions. In the 1880’s, President Theodore Roosevelt and his friends participated in hunting expeditions for deer, bear and mountain lions in the rugged landscape of the Black Hills. It was this kind of unregulated trophy hunting that led to the complete extirpation of mountain lions by 1906.

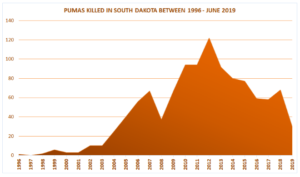

State bounties continued until 1966 despite the fact that no one was bringing in any lions and after that the slow return of mountain lions over the next 30 years earned them ‘big game’ listing in 2003 and the first mountain lion hunting season opened in 2005.

The mountain lion’s ability to adapt to a wide variety of habitats, their stealthy and secretive nature, their dispersal patterns that call for travel over long distances, and their tendency to being an adaptable, ‘generalist’ hunter are likely what have allowed the re-establishment of mountain lions in the Black Hills.

Fur Trade

The fur trade thrived in South Dakota, with one of the main trading posts on the Northern Plains being Fort Pierre. This post was run by the American Fur Company and trade was mainly in buffalo robes that the Lakota brought in to exchange for European goods. Robe production and trade reached an average of 100,000 bison robes annually by 1850. The robes that brought the most money were from bison killed in the winter months because their fur was thicker and plusher for warmth against the harsh winters there.

Bounty

From 1889 to 1966, a bounty was placed on mountain lions by the South Dakota legislature. Despite an assumed abundance of the species, mountain lions were effectively extirpated from the state by 1906 with only two reported lion deaths (1931 & 1959) occurring over the next sixty years. Concurrent bounty programs and unregulated hunting practices in surrounding states suppressed the entire region’s mountain lion population and prevented recolonization of the species in South Dakota until the early 1970s.

Unregulated Hunting

Early settlers in South Dakota set about eliminating mountain lions from the state by killing them whenever and however they could. As in so many of the eastern Plains states, whites were fearful for their own safety and the safety of their livestock, and they did not want mountain lions competing for the native game such as deer and elk. As such, lions were killed by whatever means possible, including baiting, shooting, trapping and snaring. Their populations declined through the early 1900’s until extirpation in 1906.

Trophy Hunting

Mountain lions were classified as a State Threatened Species from 1978 until 2003, when they were re-classified as ‘big game.’ The first experimental hunting season took place in 2005, justified by a number of so-called reasons including: to provide data for the state’s ‘mortality-based’ research and to provide a proactive rather than reactive strategy for dealing with ‘problem’ lions, (despite the fact that South Dakota had no problem lions) so the state could reduce the potential for lions receiving ‘bad publicity.’

Since their reclassification as a Big Game Animal in 2003, the only protection mountain lions in South Dakota have comes from the regulated hunting statutes, and those ‘protections’ are limited to only when and how many will be killed in any given year.