Feature image courtesy of Sebastian Kennernecht

Download the PDF of the New Edition of the Essential Guide to Recent Scientific Research on Mountain Lions.

Feature image courtesy of Sebastian Kennernecht

Download the PDF of the New Edition of the Essential Guide to Recent Scientific Research on Mountain Lions.

Feature image by Coexistence Ambassador Sean Hoover

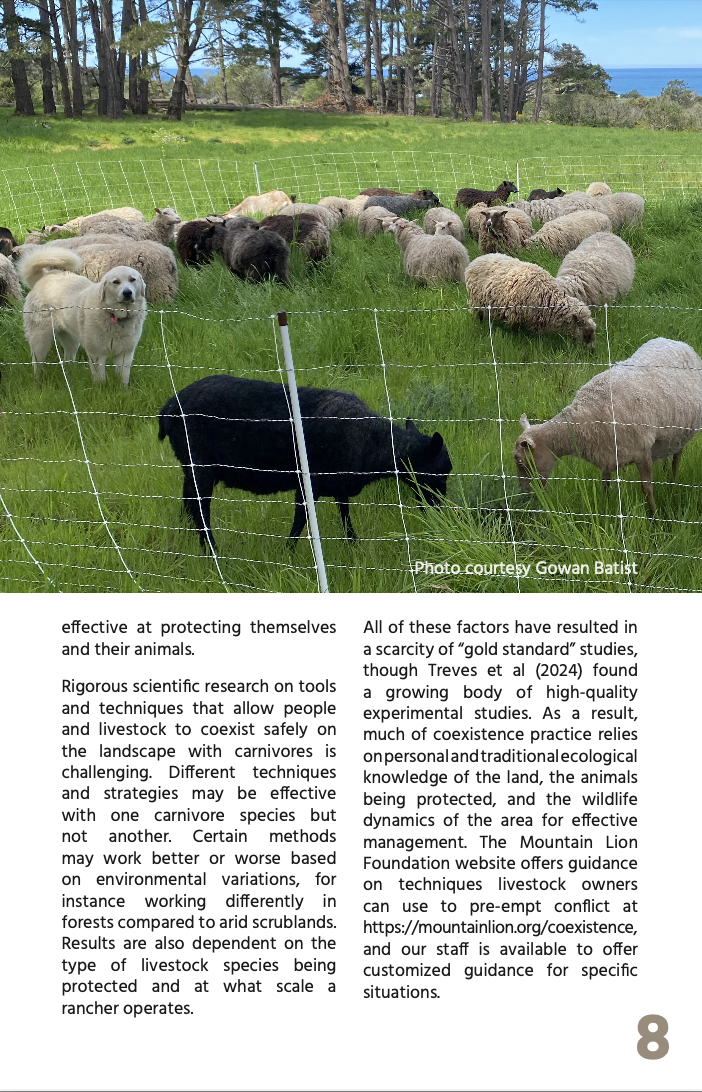

The Mountain Lion Foundation’s Coexistence Ambassadors are a group of trained volunteers in 11 states working as community advocates for coexistence with wildlife. We train a cohort of Ambassadors each summer on a working sheep ranch in mountain lion country to give them a strong foundation in practical skills. These competencies include talking to the public about mountain lions and their value to ecosystems, understanding depredations and how to identify the responsible carnivore, crisis response, productively working with community leaders, and how to use the tools of deterrence and exclusion.

The training includes hands-on exercises with electric fences, Foxlights, Gadflys, and working animals like Livestock Guardian Dogs. We also teach about the ecological importance of mountain lions and the legal frameworks of how they are (and aren’t) protected in various states.

Our Ambassadors go on to form a supportive network unlike any other. After training camp, they participate in continuing education and community support through monthly zoom meetings. Both Mountain Lion Foundation staff and Ambassadors themselves, many of whom work in the field of conservation, host these educational sessions. When volunteers are needed, the Ambassadors can be mobilized for everything from tabling at community events to helping install deterrent devices for both community safety and data gathering.

2024 was a challenging year for our Ambassadors, and we are so proud of everything they accomplished.

In Colorado, our Ambassadors fought hard to protect wild cats from trophy hunting, and strung barbed wire with staff to help a ranch recover from wildfire and become more friendly to the local cougar population.

In Utah, they worked to protect lions whose few government restrictions on trapping and hunting were recently revoked.

In Texas, they advocated for wild native cats, including the vanished Jaguar.

In southern California, an Ambassador worked as a docent for the Wallace Annenberg crossing (with training from our friends at the Cougar Conservancy and the National Wildlife Federation), and several Ambassadors served as trail docents and guides at sites like the Sacramento Valley Conservancy, the Mission Trails Regional Park, and the Tecolote Canyon Natural Park, educating the public about safe recreation in cougar country, even in one case directing skits for children that include a mother cougar and her cubs.

One of our Ambassadors ran a marathon and used an illustration of a cougar that they made for their team jerseys!

Ambassadors wrote articles and letters, and one even staffed a table at an event to educate the public about cougars in Mississippi. One Ambassador, who is also a graduate student in ecology, submitted her final project on mountain lions, and is now writing curriculum for elementary students to understand both safety and the ecological importance of mountain lions. Another Ambassador has already volunteered to engage with receptive schools with which she’s built a relationship.

After the tragic loss of a young man to a mountain lion attack in El Dorado County in 2024, our Ambassador team stepped up to provide community education and support, and to volunteer to install deterrent devices.

When Avian Flu took the life of mountain lions in a sanctuary beloved by our Ambassador, she remained steadfast in her work advocating for this vulnerable and magnificent species.

Another Ambassador, who is an amazing wildlife photographer, learned that he had passed within 60 feet of a collared lion with his camera, without ever seeing the cat. Over and over, we confirm with our experiences that in most cases, wild mountain lions seek to avoid humans and coexist peacefully with us.

In 2025 we are beginning the year with wildfires in Southern California, where several of our team are located. The fires are displacing vast amounts of wildlife including mountain lions. A video of a mother lion and her cubs fleeing fire has been shared across the internet. In the wake of a displacement event like wildfire, more human/lion conflict is likely, and the Mountain Lion Foundation and our Coexistence Ambassadors will be there to support people with knowledge and tools so we can safely share this landscape.

Our next Coexistence Camp will be held near Seattle, Washington in the early summer, with both new and returning volunteers gathering to build community and receive in-depth training. If you would like to apply to join us, be on the lookout for information coming soon.

Feature image by Collin Eckert

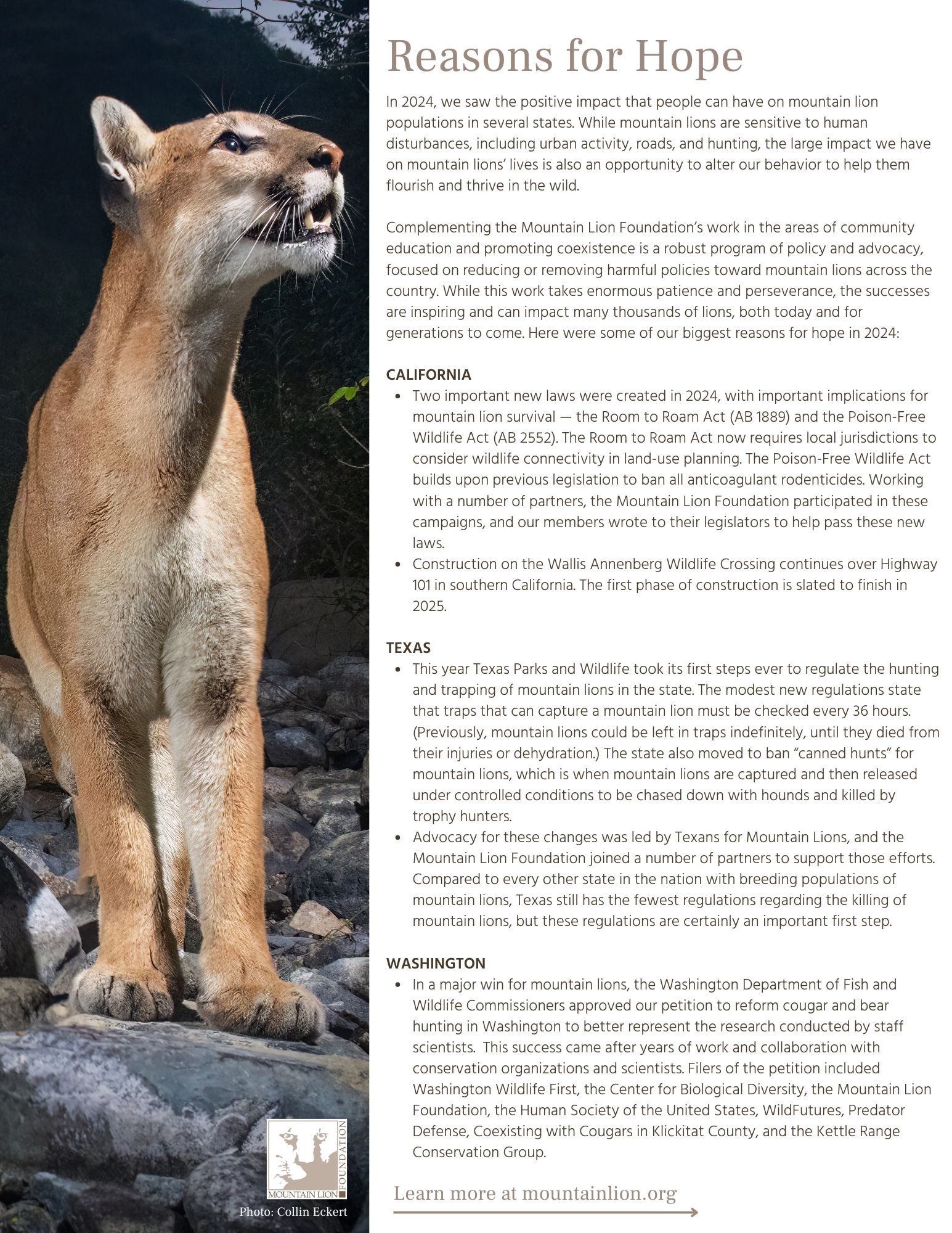

Thanks to the immense generosity of our donors, 2024 was a wonderful year to amplify support for mountain lions. The Mountain Lion Foundation is more motivated than ever to move this work forward in the new year. Here are our reasons for hope and causes for concern in 2025:

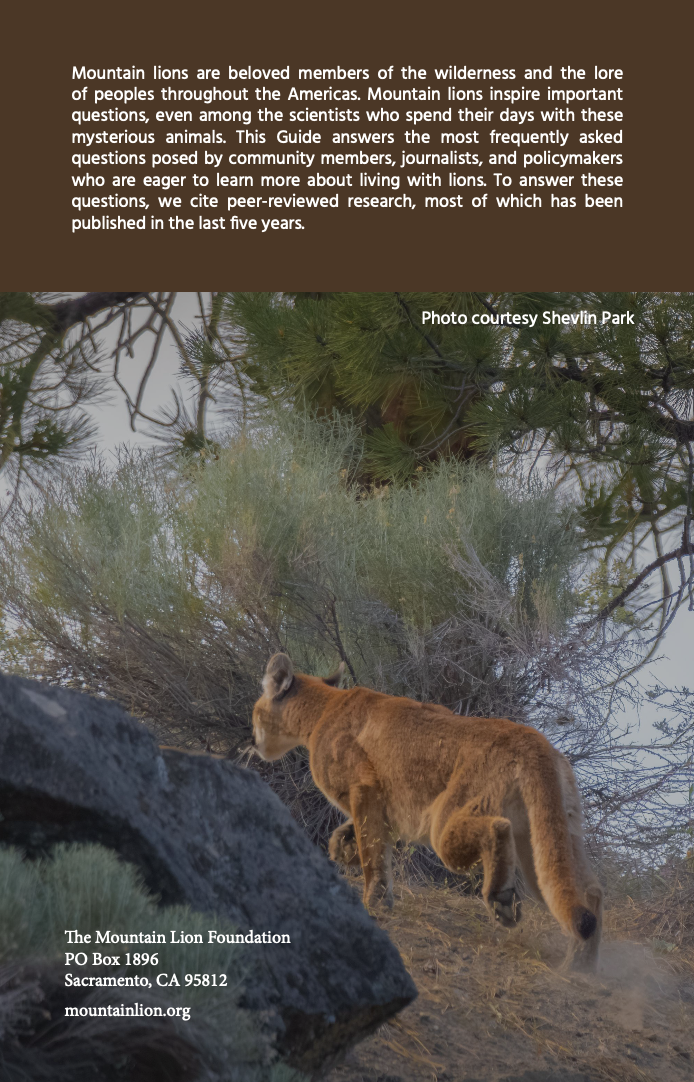

For as long as humans have lived in the Americas, they have lived alongside mountain lions. For much of that time, humanity’s goal has been to coexist as peacefully as possible, protecting humans and livestock and allowing mountain lions to exist peacefully where they live. Unfortunately, as recently as the early 20th century, mountain lions came to be viewed by many in the United States as vermin, and widespread extermination campaigns almost led to their extinction.

Today, Americans who live in mountain lion country and state wildlife agencies charged with law enforcement, better recognize the ecological importance of these irreplaceable animals. With the help of our supporters, we continue to support and encourage those efforts, and we fight for the rights of mountain lions to live lives that are free from needless and ruthless persecution. Coexistence makes life better for people, for the domesticated animals who depend on us, and for wildlife. It allows mountain lions to behave as they have evolved to behave.

We work in the field, in the courts, in state and town meetings, and in communities where mountain lions share our space. We stand up to powerful political interests and join hands with communities. We will continue to strive to save this extraordinary animal. Not just for posterity, but for THEM. They have a right to exist and live their natural lives as part of our world, keeping it wholesome and in balance. But they cannot do it alone, and neither can we.

Thank you for being our partner in this struggle for our planet, our children and grandchildren, and for the lions. Onward in 2025!

A livestock guardian dog walks his property in Grand County, Colorado. Photo credit: Brent Lyles

Register now for our December Living with Lions webinar:

Onward in 2025, for the Lions!

Wednesday, December 18 at 12pm PT via Zoom

The nature of our mission to save America’s lion often means that for every three steps forward, we stumble backwards a few paces. In 2024, we witnessed incredible milestones for cougar protections, but we also saw devastating set-backs. What is the state of mountain lion protection in 2024? What are our causes for concern and what are our reasons to hope in 2025?

Join Executive Director, R. Brent Lyles, as he reflects on the work of the Mountain Lion Foundation this year and shares his vision for our work going forward to ensure that mountain lions survive and thrive in the wild.

The Speaker

R. Brent Lyles is Executive Director of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Brent began his professional journey teaching middle-school science in rural North Carolina. Since that time, Brent’s career has focused on science education, compassionate and inclusive leadership, and environmental stewardship.

He holds master’s degrees in biological anthropology and not-for-profit management. Before joining the team at the Mountain Lion Foundation in 2022, Brent served as executive director at several not-for-profit organizations in Austin, Texas, and the San Juan Islands, Washington. Other experiences include playing in mediocre rock bands, management consulting, writing national science textbooks, and, as a young person, dreaming about someday seeing a mountain lion in the wild.

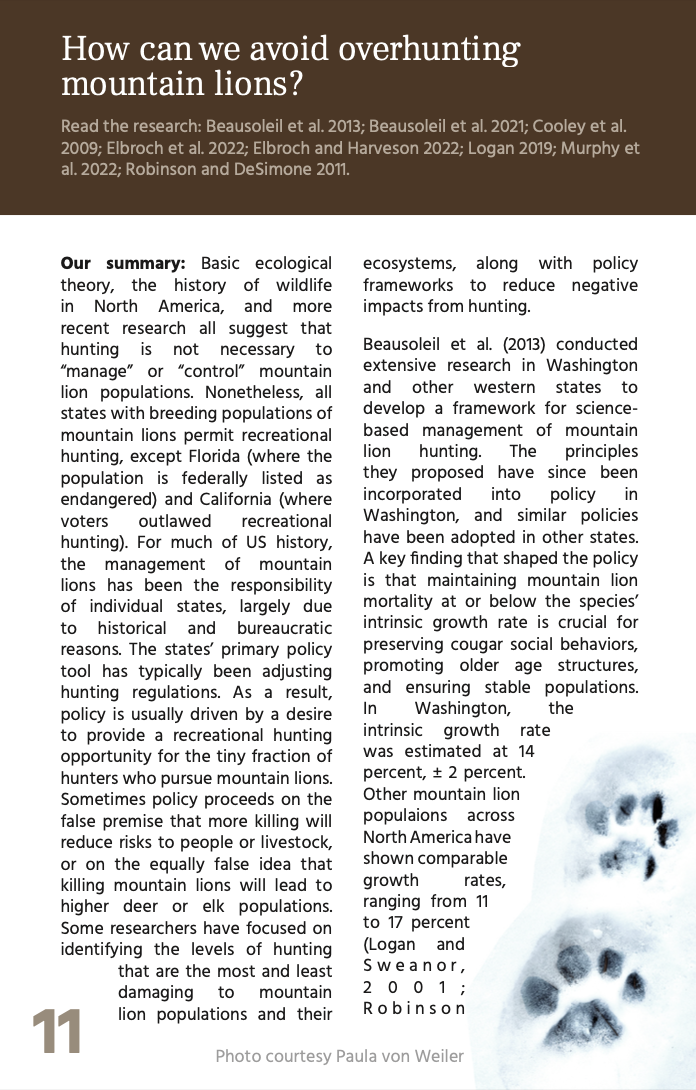

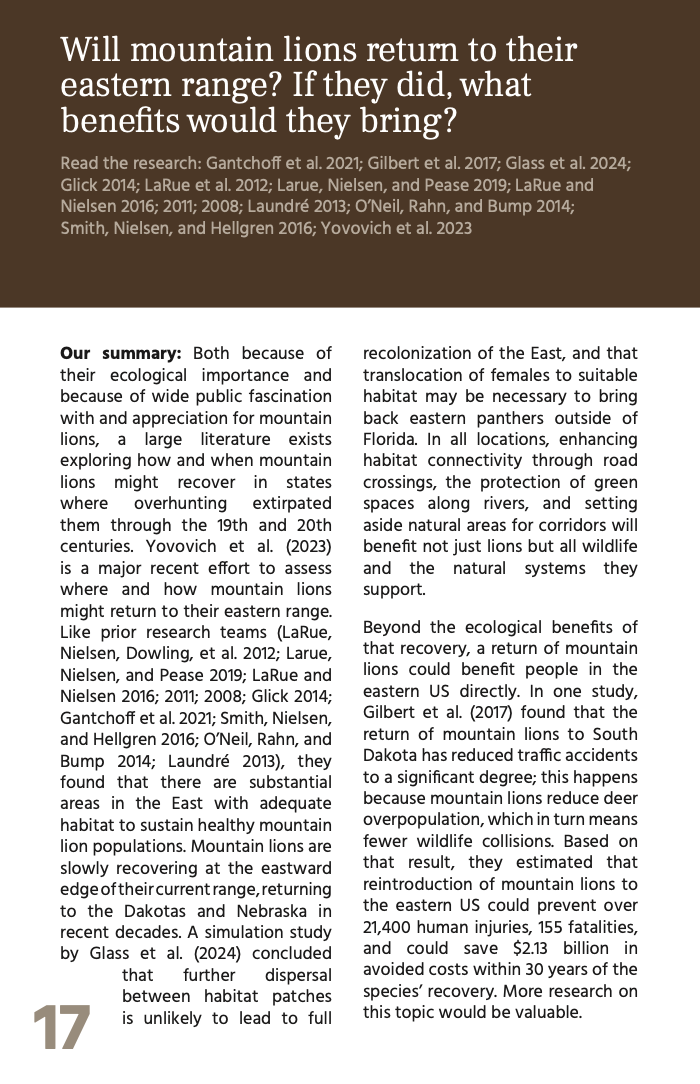

PumaGuard uses AI to accurately detect mountain lions on trail cameras and triggers sensory deterrents to keep them away from livestock. | Graphic courtesy of Aditya Viswanathan

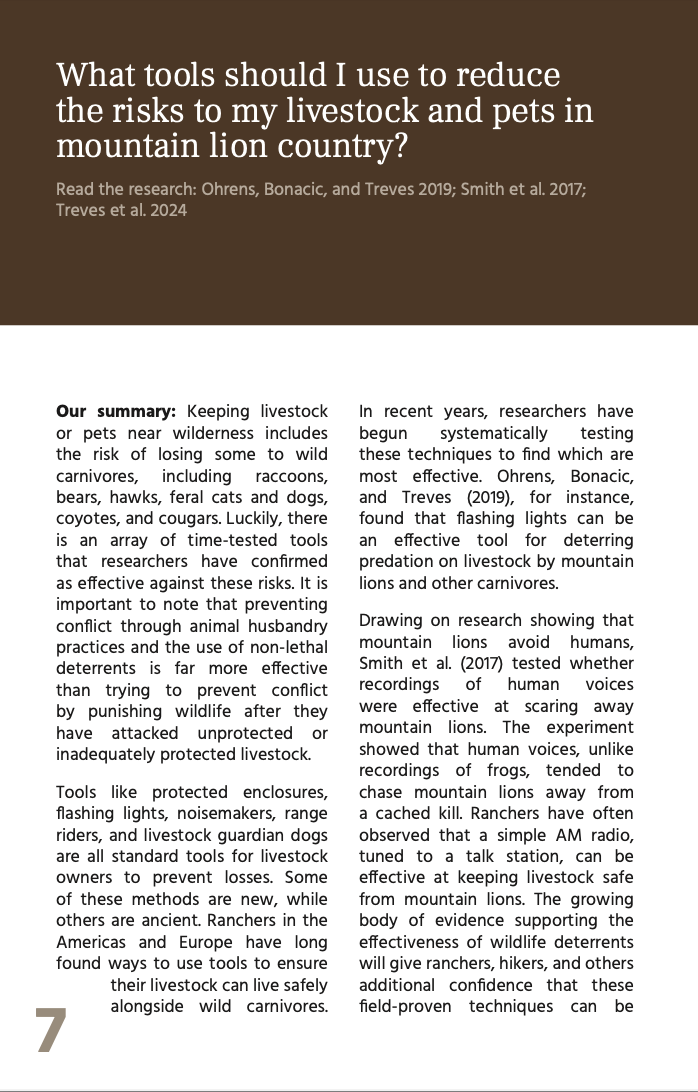

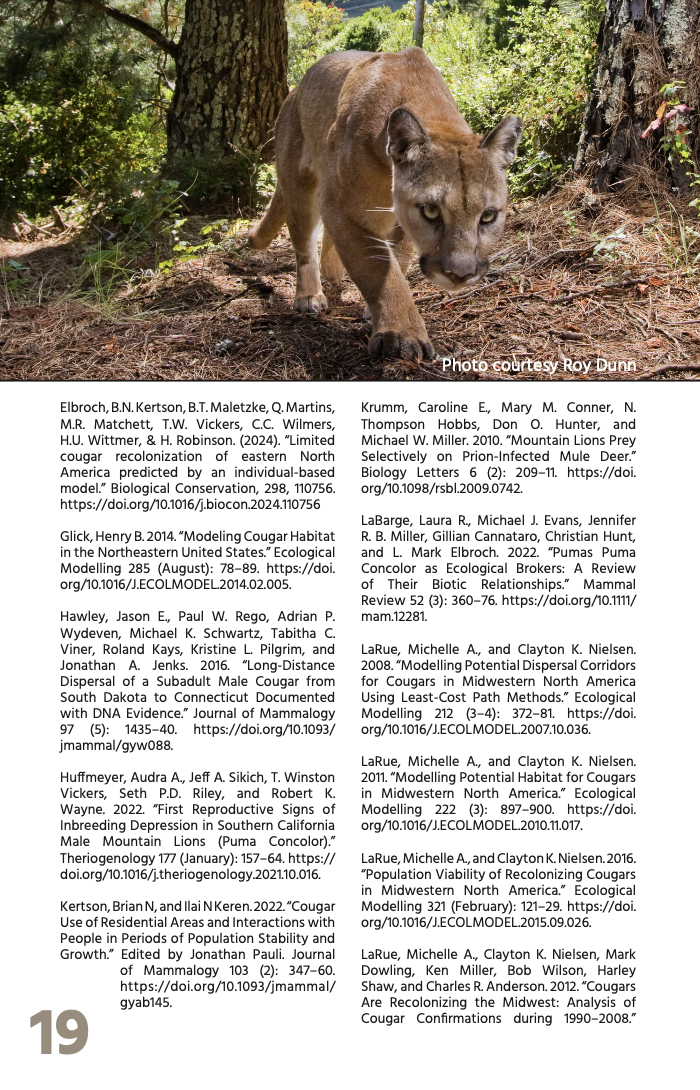

Human development and increasingly frequent and intense wildfires have disrupted wildlife habitats in western and southwestern states like New Mexico. When habitat becomes fragmented, there can be more conflicts between people, livestock, and displaced carnivores like mountain lions. Studies suggest that the sound of human voices, especially when combined with other sensory experiences like flashing lights and sporadic loud noises, are an especially effective method for keeping mountain lions away from livestock. “Stacking” deterrent methods on top of human voices has proven so effective that some sheep and goat ranchers keep a transistor radio tuned to talk radio near their flocks. The sound of humans acts as a first line of defense; if that first deterrent fails to keep a lion at a distance, then flashing motion lights, loud sonic devices, and/or livestock guardian dogs inside an electrified fence will likely do the trick. Stacking deterrent methods, as opposed to using just one that may not deter every lion every time, has proven to be a very effective way to keep both livestock and lions safe.

What if ranchers could target their deterrent stacks so that they’re activated only when there really is a mountain lion around (as opposed to a neighbor walking by)? Light and sound deterrents are most often motion-activated. That means that they’re triggered indiscriminately by movement, which may or may not come from a mountain lion. Deterrent stacks are effective; they are also the broadest-stroke approach to keeping away elusive, usually solitary feline carnivores.

Aditya Viswanathan, a sophomore, and his team of seven fellow high schoolers are refining the art and science of mountain lion deterrence. Aditya and his teammates are members of the Pajarito Environmental Education Center (PEEC) Nature Youth Group in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Their invention, called PumaGuard, is a machine learning application that detects and identifies, with 99% accuracy, mountain lions on trail cameras. When a puma is detected on camera, PumaGuard automatically triggers multiple deterrent methods in the exact area of the cat. Aditya and his team are testing the effectiveness of their tool at stables in Los Alamos stables near the students’ homes and where livestock-lion conflicts have persisted for a decade.

Members of the PEEC Nature Youth Group with Aditya Viswanathan (center back) | Photo by Ryan Ramaker, Los Alamos Daily Post

Using the Xception architecture, the algorithm achieved 99% training accuracy, 91% validation accuracy, and successfully identified pumas at the site. Our method can be deployed on a Raspberry Pi and processes images from multiple trail cameras via a local WiFi network, which enables near real-time detection. Once pumas are detected, the platform can trigger multiple mitigation responses, such as lights or sounds. This economical, scalable solution is simple to implement and holds promise as a globally applicable method for reducing predator-livestock conflicts while promoting coexistence. – Aditya Viswanathan

PumaGuard has already garnered impressive awards for the social impact and sophistication of its deployment of machine learning. It was one of four projects to win an award in the high school track of NeurIPS, the world-renowned AI conference. Of the 330 projects submitted by high school teams around the world, PumaGuard was recognized for its creative approach to the competition’s theme of how machine learning can have a positive benefit on society.

Since winning the award, Aditya has represented his team at conservation and AI conferences across North America. In October, he was featured as a speaker at the International Wildlife Coexistence Conference. In December, he is traveling to Vancouver, Canada to present PumaGuard and receive the NeurIPS award for his team. We are lucky to have him as our January Living with Lions Webinar guest to talk about how he, his team, and his fellow young adults are creatively and proactively protecting wildlife for their generation and beyond.

Fun fact: Aditya’s dad is Hari Viswanathan, the physicist and camera trapper who was featured in our 2025 Annual Calendar and our April Living with Lions webinar called Mountain Lion Spying 101.

Register now for Aditya’s webinar to learn more about PumaGuard and the future of wildlife coexistence.

Image of California mountain lion by Collin Eckert

During this past year, the Mountain Lion Foundation has enjoyed success — and faced continuing challenges. Here at the Mountain Lion Foundation, we deeply appreciate the support of our dedicated members as we work to ensure that our cougars not only survive but thrive in the wild.

Utah: In Utah, we are pursuing our lawsuit to get Utah’s HB469, one of the most dangerous laws for mountain lions in recent memory, overturned. We expect it to move forward to oral arguments in early 2025. In the meantime, we’re continuing to work with our partners like Utah Mountain Lion Conservation to educate Utahns about the importance of mountain lions and the risks of overhunting them.

Colorado: By now, you know that Colorado’s Prop 127, a ballot initiative to protect Colorado’s mountain lions from trophy hunting, was not successful. The good news is that the coalition behind that campaign, Cats Aren’t Trophies, is alive and well, and we’ll be working closely with these partners to promote coexistence and advance protections for Colorado’s native lions in the year ahead.

South Dakota: In a surprise move on October 3, the South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks Commission chose NOT to increase mountain lion hunting in the vulnerable Black Hills area. That was thanks to the many lion-friendly public comments they received, as well as input from the Mountain Lion Foundation and our partners in that state.

Washington: One of our biggest successes in the past year was in Washington state, where the state’s wildlife commission adopted important and dramatic new rules in July to prevent the aggressive overhunting of cougars. The rule change was the final result of years of steadfast advocacy and a petition filed in December 2023 by the Mountain Lion Foundation, Washington Wildlife First, and other partners from national and statewide groups.

California: Community concerns remain high in areas of California with high lion activity, and in these areas, the Mountain Lion Foundation is continuing to engage proactively in these communities, meeting with local wildlife officials and residents about safely coexisting with mountain lions.

Also in California, two important new laws that protect mountain lions were recently signed into law by Governor Newsom. The first is an expanded ban on anticoagulant rodenticides (which have outsized, harmful impacts on lions); the second is the “Room to Roam Act,” requiring local governments to incorporate wildlife connectivity in their planning. The Mountain Lion Foundation and our members, along with our many coalition partners, fought for these changes. And won!

The Mountain Lion Foundation succeeds because people like you cherish our beautiful big cats and recognize the importance of standing up to preserve our natural world and protect the creatures that call it home. Whatever we call her — puma, cougar, catamount, panther, or spirit of the mountains — she’s a magnificent and inspiring cat, and we must protect her.

Join us with a year–end donation, and together we’ll keep our mountains purring. Donate now.

By Elizabeth Bennett, PhD

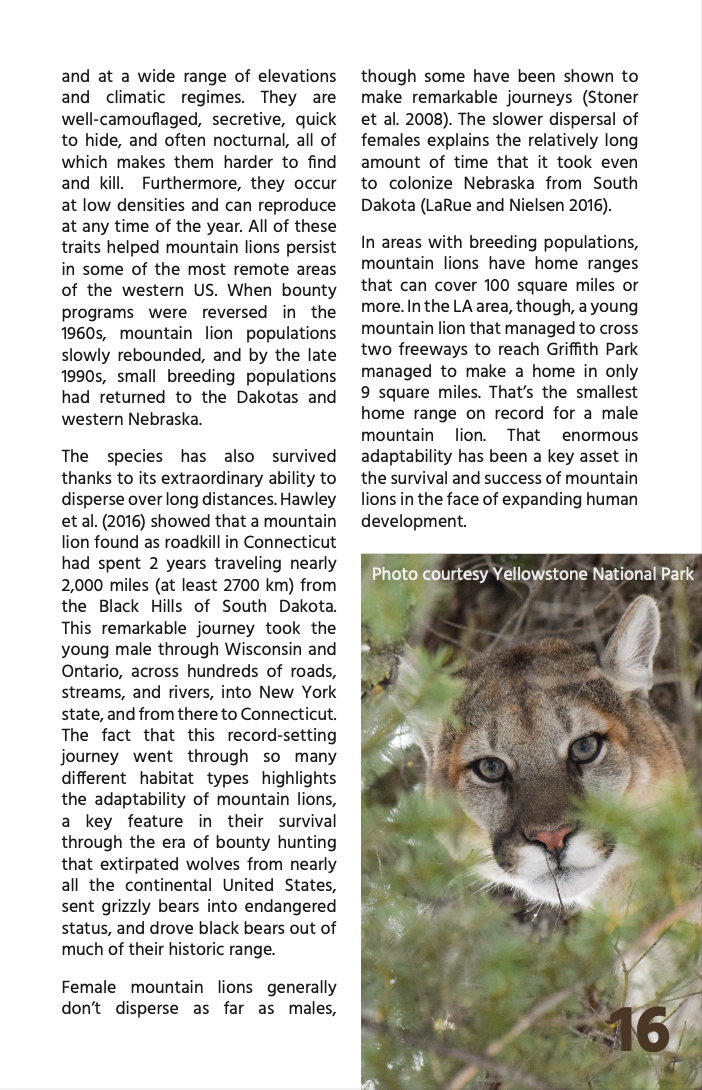

If you’ve never been to Griffith Park in Los Angeles, you still likely know Griffith Park. With just over 4,000 acres, Griffith Park is one of the largest municipal parks with urban wilderness in the country. Covering less than 10 square miles, the park is home to major Californian (and American) landmarks, including the Hollywood sign, the Los Angeles Zoo, and Griffith Observatory. The latter was made most famous by James Dean’s mesmerizing 1955 performance in Rebel without a Cause. The park itself stands for LA, and Angelenos make good use of this beautiful space in the middle of their city.

On any given day, Griffith Park is teeming with people: running, horseback riding, picnicking, celebrating birthdays, and in general, enjoying 365 days of warm California sunshine. It’s estimated that 10 million people visit Griffith Park annually. On a Saturday in mid-October, when I visited the park, there was something even more special to celebrate.

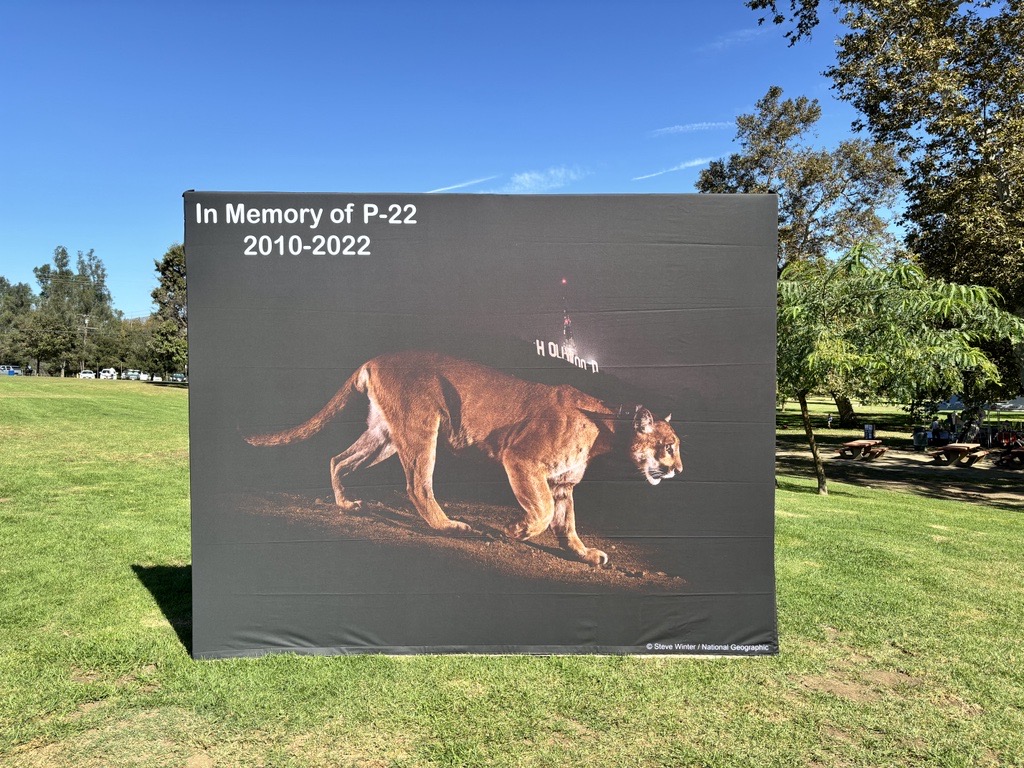

The National Wildlife Federation and #SaveLACougars have hosted the Annual P-22 Day Festival for the last 9 years. P-22 is the world-famous mountain lion that lived in Griffith Park from around 2012 (when he was first captured by a trail camera) until he was humanely euthanized due to severe injuries and chronic pain on December 17, 2022 by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. His story is extraordinary because he lived for a decade in an area about 10 times smaller than most mountain lion territories, and because he had to brave two notoriously busy highways to make it there.

For 10 years, P-22 was Hollywood’s Cat, and Angelenos loved him. They loved the idea that a mountain lion, a species known for their elusive nature, coexisted with them in this park that they also loved. In choosing Griffith Park, and braving the journey to get there, it was like P-22 chose them. And in every respect, he did.

The Annual P-22 Day Festival is a tribute to the legacy of Hollywood’s Cat. It’s a celebration of people, music, food, wilderness, animals, advocacy, ingenuity, and community. It’s an occasion to swap stories about P-22 sightings back in the day. It’s a reason to remember the mountain lion’s stirring 2023 memorial at the Greek Theatre (another iconic California landmark). It’s an opportunity to connect with people from across the state who share a love of wildlife and wild places.

And it is perhaps, most poignantly, a glimpse into how American cities could be if coexistence was adopted as a core value and wildlife was celebrated, respected, and understood on their own terms.

While other states are passing laws that increase recreational hunting of apex carnivores like mountain lions, bears, wolves, and coyotes, I’m proud to live in the only state that has chosen to protect our mountain lions from recreational hunting. I’m proud that Californians understand the innate value in protecting as much wilderness as we can and the animals that call those places home.

I’m so grateful that the world opened our hearts to P-22 and rooted for this underdog in the cat world. We have chosen to remember him and more importantly, we’ve chosen to use his legacy to propel us toward something better together.

#P22Forever

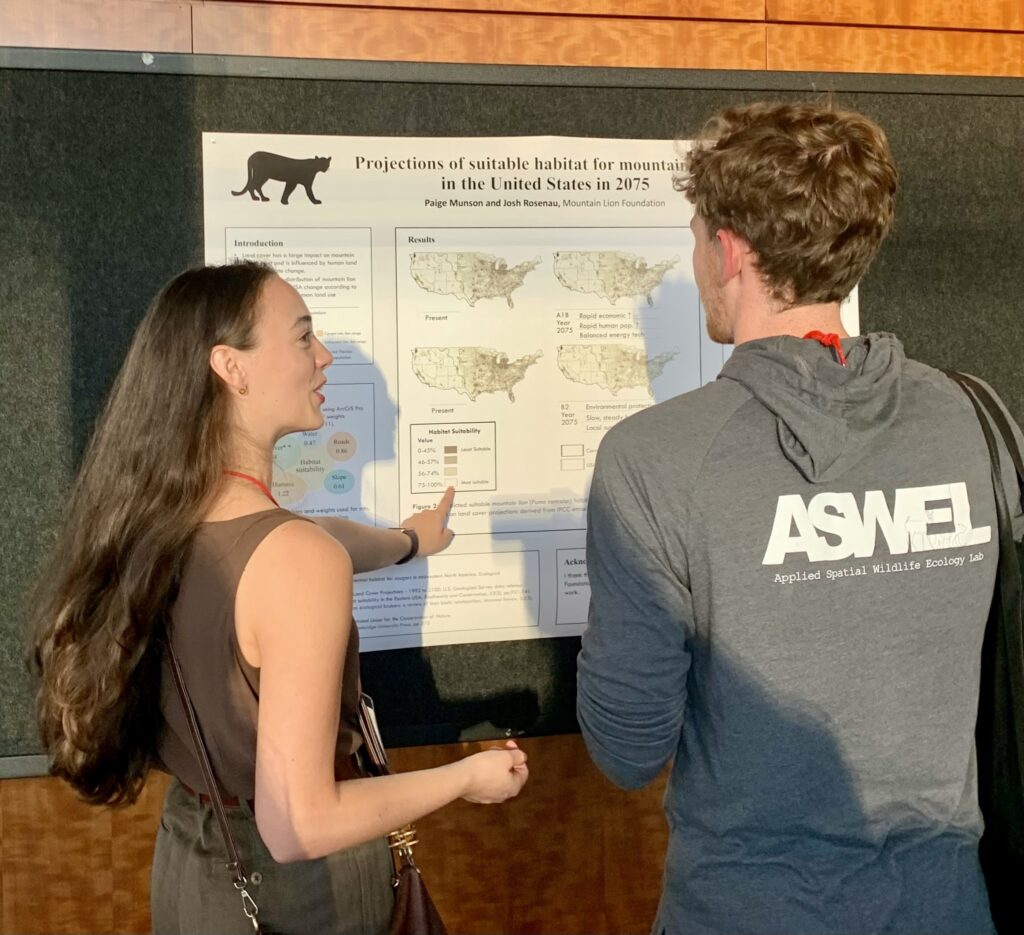

By Paige Munson, Science and Policy Coordinator

I recently joined more than 2,000 attendees at the 31st Annual Meeting of The Wildlife Society (TWS) in Baltimore, Maryland. The meeting offers wildlife biologists opportunities for professional development, time to connect with peers, a forum for sharing new and ongoing research, and a time to be inspired by the amazing stories of people in our field.

This time to share, collaborate, and connect is essential, addressing a need that goes beyond the academic to the emotional and social. As Aldo Leopold poignantly said: “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.” These meetings represent some of the few moments where wildlife scientists and conservationists can come together and feel profoundly, albeit briefly, un-alone in their work.

The meeting kicked off with plenary addresses from three conservationists who have gone beyond their research to engage in the political and cultural arenas it affects—and to remind us that they aren’t that separate to begin with.

At the opening plenary session, we heard from Julie Robinson, deputy director of earth sciences at NASA about the work they are doing to create imagery and models of the Earth’s surface. Robinson emphasized that as exciting as this work is, its usefulness hinges on effective communication with the public.

Next to the stage was wildlife biologist, James Cummins, executive director of the NGO (nongovernmental organization) Wildlife Mississippi. He shared stories of his career and emphasized that his work in policy has been the most impactful part of his career. He reminded us that: “If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.” If we can’t speak up for the wildlife we care about, no one will.

Finally, we heard from Jason Baldes, director of the Tribal Buffalo Program for the National Wildlife Federation. He shared the story of the reintroduction of bison to the Wind River Indian Reservation. To him and his community the return of bison was an ancestral food source brought back, the ecological restoration of their home, and also “bringing a long-lost relative home.”

Later I attended a TWS workshop to help scientists engage in the policy arena. There we heard stories from the CEO of TWS, Ed Arnett, and TWS staff member Kelly O’Connor about working in policy, and the challenges they faced. The challenges stem from a mix of problems: economic opposition, culture clashes, and the stifling of scientist voices.

The world is calling for the voices of scientists to help bring solutions to the problems of today. But when it comes to many topics, many scientists are unable to share their opinions due to their institutional affiliations or fear of retribution. Some scientists work towards policy by advocating within institutions, others utilize private emails to share their voice with NGOs and advocates who can use the information they share. Unfortunately, there is no one clear path for scientists to engage in policy. Some have the full ability to do so, but others are limited.

As of now, we can praise the scientists permitted to engage in policy and support the scientists who are unable or do not feel comfortable doing so.

At the conference’s poster session, hundreds of presenters gathered to share their work. There I presented the Mountain Lion Foundation’s ongoing work to model habitat for mountain lions. Throughout the night people approached my poster and touched where their home was on the map. They would tell me stories about the mountain lions in their area. For the people who lived in areas where mountain lions were eradicated, many shared that they wished the mountain lions would come back. For some they wanted the ecological services that mountain lions can provide. But for others, their hope rested in wanting to experience a bit more of the wild and magic that comes with sharing your home with an animal like the mountain lion.

As a member of the Mountain Lion Foundation’s policy team, I was proud to see that scientists were galvanized to action towards the vast array of issues facing wildlife, including policy. The Mountain Lion Foundation engages with policy at legislative levels, but also by participating in local government and state agency decision making regarding mountain lions. My time at TWS this year energized me about our work, sparked new ideas for approaching the issues surrounding mountain lions, and gave me the chance to meet new partners in our mission to ensure that mountain lions survive and flourish in the wild.

If you are someone who was closely watching the presidential election, today may be a difficult day for you, or it may be a day of celebration. Whatever your political leanings may be, I firmly believe that we can all agree on one thing: Our country’s beloved and important wildlife should not have to live their lives facing needless and ruthless persecution.

As you’ll likely remember, the Colorado-based members and volunteers of the Mountain Lion Foundation, along with our staff and Board of Directors, were “all in” on Prop 127 in Colorado, a ballot initiative that sought to protect Colorado’s mountain lions from trophy hunting. From knocking on doors to advocating on social media to helping pay for persuasive ads and staff time, we were there, working closely with Campaign Director Sam Miller and her team at Cats Aren’t Trophies. Unfortunately, in yesterday’s election, Prop 127 was not successful. Too many voters in Colorado were swayed by the opposition’s misleading and sometimes outright false messaging — and that opposition was incredibly well-funded by “dark money” PACs.

This was a big disappointment, but we are undaunted! The critically important work of the Mountain Lion Foundation continues in Colorado and across the country. I appreciate you, and I thank you for your support as a member of the Mountain Lion Foundation. The organization’s education, advocacy, and coexistence work is rooted in a deep partnership with our members, our volunteers, and the partnering organizations in our various coalitions. Let us all commit to learning what we can from this, and to using those lessons to strengthen our efforts moving forward.

Personally speaking, a setback like this tends to fire me up. It makes me mad and energizes me, and I’m ready to go roaring into the future: We’re going to knock it out of the park in the year ahead. Our mission — ensuring that mountain lions survive and flourish in the wild — is too important to do anything less.

Onward in 2025, for the lions!

R. Brent Lyles

Executive Director

Guest Blog by Chris Smith, Wildlife Program Director, WildEarth Guardians

A few years ago, I was poring over trapping regulations in various Western U.S. states, wondering what state stoops the lowest in terms of facilitating the suffering of animals and allowing people to privatize and kill the public’s wildlife. Nevada stood out, and not in a good way. No bag limits. No trapper education requirements. No mandatory reporting. And a 96-hour trap check window.

Yes, in Nevada, an animal can languish in a trap for up to 96 hours legally. The longest of any state in the West — longer than Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana.

We want to change that.

Among the species who suffer from these archaic “regulations” are mountain lions — charismatic, secretive cats who are critical to ecosystem health even though we rarely get to see them.

Lions aren’t even supposed to be trapped in Nevada — they are a non-target species. But too often lions are caught, injured, maimed, and even killed.

On October 8th, WildEarth Guardians, the Mountain Lion Foundation, and the Nevada Wildlife Alliance submitted a petition to protect mountain lions from the unintended consequences of this cruel trapping practice.

The petition outlines eight recommendations, all of which are not only common-sense adjustments to policy but also important protections for mountain lions:

Nevadans, we need your help! Please send an email to Nevada Board of Wildlife Commissioners requesting that they accept our petition and rein in the trapping chaos across the state. If you are a resident (or know a resident), click here to send your letter!