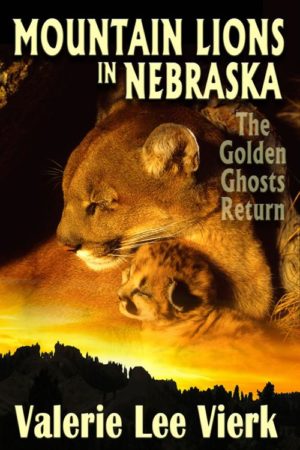

Rewilding the Midwest: An interview with Valerie Vierk, author of Mountain Lions in Nebraska—The Golden Ghosts Return

with Valerie Vierk, author of Mountain Lions in Nebraska—The Golden Ghosts Return

The historic range of the America’s mountain lion spanned from coast to coast of what is now the United States. After the combined forces of a devastated deer population and excessive hunting of lions the population dwindled to nothing in the Midwest and Eastern regions of the US, with a small Florida population taking refuge in the swamps. With the protection of mountain lions in states like California and the regulation of hunting in western states where they are categorized as a big game animal, the mountain lion is recovering.

Midwestern Nebraska shares a border with western states supporting established mountain lion populations. Dispersing lions have been making their way into Nebraska for years. Unlike other recovered animals like the gray wolf, the mountain lion is returning to its historic range unaided yet is unlikely to establish stable populations without protection. Nebraska has made rewilding efforts before like the reintroduction of the river otter in 2017. This reintroduction was a great success and now river otters have stable populations within the state. By urging the Nebraska Game and Parks to offer protection for recovering mountain lion, as done before with otters, we may see a wilder Nebraska once again.

- Firstly, Let’s talk about the title. Mountain Lions in Nebraska–The Golden Ghosts Return. Tell me about that. Where did they go? How did we wipe this iconic cat from that area?

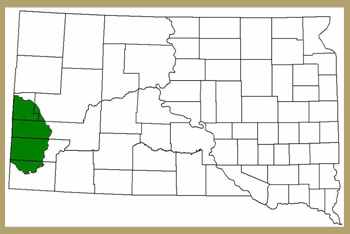

According to the literature, the Golden Ghosts were extirpated from Nebraska by about 1900. In my research, I did discover a few scattered alleged sightings after that, but they were mostly gone. According to the late Dr. John Laundré, who passed in March 2021, cougars were never that plentiful in Nebraska. (See his book Phantoms of the Prairie–The Return of Cougars to the Midwest (2012). The reason he gave was because the cats didn’t venture too far out on the prairie because of wolves. Although a cougar could dispatch a wolf with one blow from his powerful front paw, a pack of wolves was more than any wise cougar cared to deal with out on the treeless prairie. Thus, Laundré wrote that the cougars stayed close to the rivers and streams to hunt deer. He called them “River Cats.” He stated that an exception to this was the Pine Ridge in northwestern Nebraska that had good hunting cover for the cougars. (It still does because the land is too rough to be farmed.)

Yes, Nebraska has lots of waterways, (see map in the book that lists 80,000 miles of waterways), but there were still a lot of open spaces (prairies) where cougars probably were not real comfortable traversing. In historic times, there were more trees radiating out from the rivers. Now with the land being altered by farming, the border of trees along the rivers is much thinner.

Nebraska does have quite varied geography, with the eastern third being much more treed, and more rainfall. Central has less trees and less rainfall, and western even less trees and rainfall. Also, these three regions are also reflected in the length of the grasses. Now, only a tiny portion of the state is native grassland.

Although cougars were hunted some in the early days because people feared them, both for themselves and for predation on livestock, I believe the primary reason for them disappearing from Nebraska was that the deer population was nearly wiped out by 1900. Nebraska is home to two species of native deer – white tailed and mule, with the former being much more common. In the early years before 1900, there were little hunting protections for deer, and thus they were nearly wiped out. It’s hard to believe, because they were so numerous. I originally had a chapter in the book devoted to the deer, but I had to cut it as the book was getting too big. These big cats need big game to survive because a bunny wouldn’t go far with them, especially a mother with hungry kittens. As the deer went, so did the cougars.

(I want to add that I contacted John Laundré shortly after I read his book. It was very helpful to me since he focused on the cougars returning to the Midwest, and the book had sections on all those states, including Nebraska. He wrote back and sent several of his essays dealing with hunting etc. When my book was finished, I tracked him down at his last know place of employment, and sent a letter. I thought it strange he didn’t respond, and then three months later I learned he had died. I was very saddened. He did so much research on cougars for many years.)

- Let’s talk about the early establishment of bounties, what that entitled and how that contributed to eradicating the Nebraska lion?

I write about these bounties in my book also. The bounty system started in the original colonies on the east coast, and spread west as the country was settled. (The Mountain Lion Foundation has a timeline on their website that was very helpful.) Unfortunately, a lot of Nebraska residents had the prevalent mindset against predators, and this fed the bounty system. We now know that predators are necessary for a healthy ecosystem, but they didn’t know that back then. In my research I found information on bounties in Nebraska in an 1881 statute and later. Apparently, the bounty wasn’t statewide, but only in counties that voted for it. I wasn’t able to determine from my limited research on this subject what counties participated.

It sounded like a grisly procedure whereby the hunter/trapper would present the ears to the county clerk. Sometimes there was “double-dipping” whereby the hunter/trapper would present the “scalp” in one country and then go to another to collect again. One website stated that because of the fraud, some places started defacing the scalp so it couldn’t be used again to collect. I suppose some agencies started collecting the scalps and then disposing of them so they couldn’t be used again.

This Nebraska 1881 statute listed mountain lion scalps as worth $3.00. I wasn’t able to find any records on how many were collected in various years, although possibly if I had conducted more extensive research, I might have found some figures. Money is a good incentive, however, and thus some people would engage in bounty hunting. Whatever the number of mountain lions killed for bounties, it all chipped away at the population, especially if they were females. There didn’t seem to be any mercy shown for even kittens. They were all just considered vermin.

In the 1960s, the bounties started being dropped in the western states, and replaced with legal hunting seasons. While it doesn’t seem like much of an improvement, it was a little better for the lions because at least part of the year the season was closed.

- How triumphant has the return of the Puma been and how have they been received?

That’s a mixed bag. For people who are fascinated with cougars, like me, it is exciting. For livestock producers, most of them didn’t welcome the return. I think a lot of the biologists are excited by the return, but at the same time, trying to “manage” the big cats is a headache because it is a controversial subject. A Nebraska biologist summed it up very well when he said something to the effect that some people want all cougars killed and some don’t want any killed.

What is impressive to me is that the “comeback” cats did it all on their own. There were no expensive government-financed reintroductions like with the wolves in Yellowstone Park in the mid-1990s. The cougars did it on their own, in spite of what some people believe, that the state wildlife agencies “stocked them.” The land and the habitat have in most cases, been seriously changed since the ancestors of our modern-day cougars roamed. Most of the prairie has been plowed up for row crops, and of course, there are many more people on the landscape, and more houses. Cougars have a tough go of it to navigate all of this. Thus, I admire that they have recolonized some of their old haunts. They didn’t announce their coming; they just came, and caught us napping.

- The book title is deceiving; it says Nebraska but it also evolved into a study of several neighboring states. How did that happen and what did you discover?

Originally, I planned for the book to be mostly about cougars in Nebraska, but the more I researched and learned how the populations are connected, I decided it would be kind of silly not to write about what was happening in Nebraska’s neighboring states. When I started the book, I honestly had never thought about or knew that cougars had been hunted in the western states for 50 years or more. Nebraska’s cougar populations aren’t just a little island; new cougars and constantly moving in from other states, and some are moving out.

I actually researched and wrote chapters on North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan, but had to cut those chapters because the book was getting too long. I am just so interested in cougars and with the Internet, it is so easy to research them, that I went off on tangents and then had to rein myself back in and just write about Nebraska’s neighboring states, with the exception of California.

So, readers are getting an extra bonus with the chapters on the neighboring states even though the title may initially lead them to think the book is all about Nebraska cougars.

- You discuss, in depth, the impact of trophy hunting and even devoted an entire chapter to California’s trophy hunting ban. Let’s talk about the catastrophic impact of hunting, not just on the puma species, but on all the native wildlife impacted by their loss.

I think a lot of humans don’t realize (or want to realize) that most, if not all animals, have a social organization. We know ants and bees have a well-organized social system, so why wouldn’t an animal of a higher class have one? I call this not wanting to believe this “human arrogance.”

In the 1960s, Dr. Maurice Hornocker and Wilbur Wiles and Wiles’ two hounds trapped and studied cougars in the wilds of Idaho. It was ground-breaking research, and what they learned from this was that cougars have their home ranges. A large male patrols his “kingdom” which usually includes four to five females and their kittens. He keeps (or tries) to keep out other males who may want to take over this kingdom. This helps protect the females and especially the kittens from intruding males.

Later, researchers learned that it is an ordered society which can easily be disrupted by human hunting. If a reigning male is killed off, several new ones will move in and this can cause danger and chaos in the kingdom.

My biggest grievance against hunting cougars is that if the females are killed, they often have dependent kittens that will be orphaned. A kitten under a year doesn’t have much of a chance of survival because they don’t know how to hunt very well. (Their canine teeth aren’t even fully erupted until they are about 16 months old.) Sure, by the time they are four months old they probably can run down a bunny or a squirrel, but they need a lot of meat for their growing bodies. As for them taking other smaller prey, porcupines are dangerous unless they can be flipped on their bellies to avoid the quills. Raccoons also are pretty formidable to an inexperienced kitten.

Starvation is the leading cause of death of orphaned kittens. I read an article by a researcher who followed an orphaned kitten that was collared. It took the kitten 50 days to starve to death. That’s a long, painful death. The researcher felt very bad about watching this tragedy, but he was charged with studying the natural life of the cats and did not intervene.

I did my own calculations on how many kittens are orphaned each year due to hunting. I did conservative calculations and then the more standard and came up with about 1,600. A few weeks later I ran across a number the Mountain Lion Foundation had stated: about 1,500 per year. However, one orphaned kitten due to hunting is too many for me.

Cougars are one of the few (or maybe the only species) that humans hunt when they have dependent young. The rule of thumb is that females are pregnant or have “kittens on the ground” about 75% of time. That doesn’t leave much leeway for killing a female that is “safe”.

We hunt deer in Nebraska and most other states, but the seasons usually start in November when the fawns are five to six months old, and can survive if their mother is killed by a hunter. Also, the fawns don’t have to hone their hunting skills. They merely have to reach up or down to graze or browse.

As for the trapping seasons, the same is true. These seasons start in November or December in most states, and by then the young of the spring are old enough to survive on their own. Even bobcat kittens usually are old enough by December 1, when the trapping season starts in Nebraska. That is not to say I am in favor of trapping.

Nature is all connected. I like to say that “Mother Nature” is smarter than man. For instance, deer need their predators to keep them from overpopulating their areas. But with the serious reduction in predators, deer populations started getting out of control in the early 1940s or so. Now days, we have hunting seasons to thin them out so they don’t starve to death or overgraze their areas. John Laundré wrote about the eastern forests groaning under the assault of the armies of deer. Native wild flowers were devoured, and then noxious weeds took over the forest floor. Shrubs and small trees were damaged or killed by the voracious deer. Don’t get me wrong– I love deer and greatly enjoy watching them in my area. I’ve written essays about my wonderful experiences observing them. But we aren’t doing them any favor by letting them get so numerous so that they may starve to death in severe winters.

- What is the current status of the Nebraska cougar? What does the future look like for them? Are we in danger of losing the golden ghost again?

Since cougars are legally protected now, I don’t think they will ever be extirpated from Nebraska again. However, I believe there is considerable illegal hunting of them, or poaching. To some people, cougars are “shoot on sight” animals and they don’t really care that the legal hunting season is closed. Some people respect the law; some don’t.

But the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission (NGPC) understands they have to manage them for hunters and nonhunters alike. The “animal people” of the state have made their voices heard via letters to the editors of various newspapers, as well as letters to the NGPC in defense of cougars. To a lot of people, predators are no longer considered undesirable.

The last scat survey conducted by the NGPC stated that the cougar population had decreased in the Pine Ridge. I think it was down about 20 animals. What caused that? Illegal hunting? Cougars moving on? I’m not sure, but I suspect human interference had quite a bit to do with it.

As for the cougar population in the rest of the state, surveys haven’t been done. It is labor intensive work and expensive. Nebraska has 93 counties and cougars have been spotted in about 2/3 of the counties. How many exist in the state? I’ve never heard an estimate. It’s hard to count something you can’t see, and an animal that roams around a lot. One day he/she may be in Nebraska, and the next day cross the Kansas line. I’ve penciled out some of my own statewide estimates, but I don’t feel comfortable giving those as they would only be speculation.

- It took seven years to write this book. What kind of background research did you have? Was it your deep passion for wildlife that committed you to such an enduring task?

I’ve been fascinated with cougars since childhood, but at the beginning of this project I didn’t know a lot about them. So, I did massive amounts of research for the book and greatly enjoyed it. (That’s partially why it took seven years to write the book. I kept reading and researching.) I have many plastic totes sitting in my basement and will keep this research for several years. With the Internet, it is so easy find information. The on-line newspapers provided lots of information. Also, I purchased about 20 “cougar books” during my research. Most are fairly current, but I also like to read the older books just to see what the author had to say about cougars 30 or 40 years ago. I love old books and like to compare what was “common knowledge” back then to what may now be proven not accurate at all.

Trail cameras have opened up the secret lives of cougars. Researchers used to think females took great pains to keep their kittens away from the males, even a male she knew. Now cameras have shown adult males sharing kills with females with kittens. We have also learned that cougars are much more altruistic to each other than we ever dreamed. Researchers have documented a few cases of females adopting orphaned kittens.

Yes, I have always loved nature/wildlife, and thus it was natural that I would want to write a book about cougars. I read a lot of nature books for kids when I was a kid, but usually the predators were portrayed as bad. Luckily, that mindset has changed quite a bit.

- Have you yourself even seen a lion in the wild?

No, and I sure would like to! But hopefully not when I am walking along the river on a nature hike by myself. There have been several sightings of cougars very close to where I live though. By close I mean within a mile of my house right along the South Loup River.

Just this summer (2021) three of our neighbors called my husband with reports of sightings. The first one was on August 6 when two neighbors saw the cat independently about ½ miles from my husband’s farm. (We got married in 2017 so I kept my house right by the river. I split my time between both places.) The neighbors saw the cat early morning, about 6:30. It is daylight by that time in my area. The cat ran in front of the pickup of one guy out checking pivots. The other guy saw the cat as he trotted just out of the boundaries of his yard. The man was inside, but got a good, long look and both were certain it was a cougar. (I am too.)

Then on September 3, another neighbor called my husband at 9:30 p.m. with the report that a cougar had run right in front of his pickup on a country road about two miles from our place. He too was certain it was a cougar because he was in the headlights and the long tail was visible.

I jumped in my car and drove up to the site, as the cat was heading toward an abandoned farm site that had lots of trees but no buildings anymore. We thought it would be a good place for him to hole up. I thought maybe I’d get lucky and see the cat recrossing the road, but no luck. I didn’t get out of my car to go look!

There have been two other sightings in recent years within a mile of my place by the river. I write about them in the book. I waited 50 years to finally seeing a whooping crane in the wild. That had always been my dream and it came true four years ago. My new dream is to see a cougar in the wild but I don’t have 50 years to wait!

- How do Nebraskans seem to feel about mountain lions in the state?

I’d say a lot of people are concerned about their welfare. The NGPC has commented that people are very interested in cougars. I don’t think anyone has ever done a survey, but with most of our human population in the eastern part of the state, if we were to do a ballot initiative to stop hunting, I think it would pass. Generally, I think people who don’t have livestock feel more tolerate than those who raise livestock. However, I think it’s highly unlikely that this issue would ever come to a ballot initiative like in California in 1990.

In my immediate area, I haven’t experienced too much hostility for the big cats, although one man (a cattle producer) told me he would shoot a cougar and not report it. For years I was in the habit of asking people if they’d ever seen a cougar. Amazingly, a lot knew someone who had even if they hadn’t. The most common response I heard was “They’re out there.” I’ve only talked to one man who thought a cougar got one of his calves in my area. Another man saw one when he was rounding up his cattle and when I asked him how he felt about a cougar close to his cattle. He said something to the effect that with all the deer and turkeys around, he wasn’t too worried about a cougar preying on his calves.

However, some people keep quiet about their true feelings about cougars, so it can be hard to judge opinions. I’d say generally that people in the western part of the state have less tolerance for cougars since that is where the biggest populations of cougars roam and they fear for the safety of their children and their livestock. Where I live in south-central Nebraska, I have never heard of a confirmed case of a cougar killing a calf. The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission holds to a high standard on these reports of livestock killed. They generally will come out and inspect the carcass. Often, they don’t agree with the owner of the animal that thinks a cougar killed the calf or goat or sheep.

- If people want to get involved in conservation of mountain lions in Nebraska, do you have any advice for them?

I believe in respectful letters to the NGPC and letters to the editor of various newspapers and I have done both many times. Also, testifying at the meetings when the NGPC is debating whether or not to hold a new mountain lion hunting season. So far, the nine commissioners have all voted as a block for the seasons. The commissioners represent hunting, fishing, trapping and livestock interests. (Last year the governor appointed a woman as a commissioner. I believe she was the first ever.) As for “cat ladies” like myself being appointed, that is probably a distant dream. Still, it is good to keep up the lobbying in favor of preserving our big cats.

There was a Facebook account for mountain lion advocates in the Omaha area a couple of years ago. I don’t if it is still active. There is quite a network of people in various states who advocate for cougars and I have recently gotten connected with a few of them, including a couple of women in the East. There is power in numbers.

- What inspired you to write this book?

When I started the book in February 2014, Nebraska was one month into its first legal mountain lion hunting season ever held. There was a lot of hoopla about it in the newspapers, complete with a photo of a young lion lying on a limb looking down at the hunter who was preparing to shoot him out of the tree from close range. Having dogs chase and tree the lion and then the hunter strolling up or riding up on his 4-wheeler is not sport to me.

That photo upset and angered me and was the catalyst for starting the book to try to help the lions. I wanted to try to change some minds in favor of helping the lions that are only trying to survive in their heavily fragmented world because of human encroachment.

- What do you find most interesting about mountain lions?

I’m fascinated by all cats because of their grace, agility, and athleticism. When I visited the Wild Animal Sanctuary in Colorado, I saw a huge tiger leap up onto a wooden perch so gracefully, just like my house cats do. I am impressed that cougars are so fast for a couple hundred yards, although they can’t maintain that pace must longer.

Mountain lions are fascinating because they are so stealthy. I think that scares people sometimes, but it is also alluring that they can be around and humans don’t even know it until they happen to catch a fleeting glimpse or shock–find a cougar image on their trail camera when they were expecting a deer.

I am also very sympathetic to the “single mothers” that have to leave their young kittens to go hunt for themselves when the kittens are still nursing. The African lionesses have a support system as they live in prides. Not so with the cougar mothers. Then when the kittens are a little older, and are traveling with their mother, it is still a risky time if the little family encounters a wolf pack or other predators. Kittens can’t climb trees until they are about four months old.

- What is one thing you wish people would understand about mountain lions?

That they are not killer cats that are after humans. Yes, there have been about 26 human deaths in the last 110 years in North America, and no one wants to see a human killed, but it is so rare that the cats hardly deserve to be labeled a big threat to humans. If a lion comes into your house, it is in your domain, but when humans recreate in lion country, we are in their homes. With more people recreating and more lions since the bounties were dropped, there are bound to be more encounters. Humans can modify their behavior to keep themselves safer in lion country—but lions can’t undo eons of evolution. They are what they are. It is extremely rare for them to see humans as prey.

- Are you seeing any efforts made in Nebraska in terms of people trying to coexist with these wild cats?

I think the state newspapers and the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission have done a pretty good job of trying to educate people about the cats. They have repeatedly published articles on the things to do if you encounter a lion. There seems to be considerable empathy for the cats that have turned up in towns and then been destroyed. My book documents cases of people expressly stating they don’t want a lion harmed that is on their property outside of town. It’s kind of difficult to gauge public opinion without doing surveys, and even they can be flawed, but I’d say the majority of Nebraskans are fairly tolerant of the big cats moving back in.

As with most subjects, education helps.

Also, in the Mountain Lion Response Plan written by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, it states that mountain lions are a native species and an integral part of our wildlife or something to that effect. Yes, Nebraska has a “no tolerance” position on cougars coming into town, but at least if they are out of town and not bothering any one, they are to be left alone. I hope someday the “no tolerance” position can be amended.

- What is one of your favorite names for the mountain lion?

I’ve always liked cougar since I was in high school. It’s kind of a family joke that my maternal grandfather called them “crugers”. I really love Klandagi the Cherokee name for the cats. It means “Lord of the Forest.”

- What are your thoughts on mountain lions dispersing eastwards? Do you see these cats reclaiming parts of their historic range? What do you think it would take to improve social tolerance of mountain lions?

I think the cats will keep moving eastward, but it will be a journey fraught with obstacles, many deadly. They’ve been spotted in Illinois and I think Ohio. Also, some people think they are already on the East coast. Tennessee documented a female cougar that they thought had come from South Dakota! And let’s not forget the “Connecticut Lion” as I call him, who made his way from South Dakota to Ct. His remarkable travel was documented in Will Stolzenburg’s book Heart of a Lion. I so admire that young lion and his biographer who told his story. I think that boys’ school where he was spotted should erect a small monument in his honor.

The Cougar Rewilding Foundation, formerly called the Eastern Cougar Foundation, tracks alleged sightings and lobbies for the return of cougars to the East. Viewing their website is interesting. It’s fun to speculate–are wild cougars there or not? Most wildlife officials believe that there may be some formerly captive cougars roaming the East, but not wild ones.

It’s very interesting to access the website of the Cougar Fund to see the confirmed sightings. I mostly concentrated on cougars in the Midwest and the West for my book, but I would love to research more on the eastward sightings. Right now, I just don’t have time as I have two other books that are written and I want to get published. These are novels, with no cougars in them–yet, although I may add one in a slight revision of the novel that is partially set in Nebraska in the late 1880s.

I think for the cats to reclaim their former ranges east of the Mississippi mostly depends on human tolerance. The East has huge tracts of national forests where hopefully the cats could live without being hunted or molested by humans too much. Again, educating people about the cats will be very important. It’s a fine line to education people about them without scaring them. For instance, cougars can be attracted to small children, and parents need to know this when they are out hiking with young children.

I’ve often thought of parks hiring “trail walkers” i.e., big college guys with phones who could easily be called if a person sees a lion and is afraid. Or maybe the guys could ride bikes to get them to an emergency situation faster. Simple things like that might prevent a possible tragedy for humans and lion alike.

I think in 20 years we could have a small wild cougar population in the eastern forests. Some people think a few are there now. But the cougars aren’t talking . . .

The END

Iowa has been without large carnivores for many years. Large carnivores maintain healthy prey populations by removing sick members. They also promote biodiversity in multiple ways. White-tailed deer have been shown to overgraze on native plants first, allowing for the spread of invasive species and loss of plant diversity. Large carnivores regulate prey population numbers, reducing overgrazing, which promotes plant diversity. Additionally, carrion from large carnivores has been shown to support scavenging animals.

Iowa has been without large carnivores for many years. Large carnivores maintain healthy prey populations by removing sick members. They also promote biodiversity in multiple ways. White-tailed deer have been shown to overgraze on native plants first, allowing for the spread of invasive species and loss of plant diversity. Large carnivores regulate prey population numbers, reducing overgrazing, which promotes plant diversity. Additionally, carrion from large carnivores has been shown to support scavenging animals.

with Valerie Vierk, author of Mountain Lions in Nebraska—The Golden Ghosts Return

with Valerie Vierk, author of Mountain Lions in Nebraska—The Golden Ghosts Return

them in our thoughts and hope that he has a full and speedy recovery.

them in our thoughts and hope that he has a full and speedy recovery.

folklore of Appalachia. She hopes to make her readers look at the world they’ve always seen, and see the world they’ve always envisioned.

folklore of Appalachia. She hopes to make her readers look at the world they’ve always seen, and see the world they’ve always envisioned.