Despite uneasiness over cougars, runners are still drawn to foothill trails

By James Raia– Special To The Bee – (Published April 23, 2004)

COOL – A few minutes’ drive past the firehouse and a row of storefront businesses, the gated hamlet of Auburn Lake Trails extends into the rolling foothills toward the El Dorado National Forest.

Large wooden markers with white block letters replace green metal street signs and designate names such as Grouse Ridge Trail, Big Nugget Trail and Gravel Gulch Court. At the community’s boundary, expansive homes, asphalt roads and horse stables end and Secret Lake Trail merges into a trailhead. A half-mile farther, the route intersects the Western States Trail.

On foot, it’s 85 miles to Squaw Valley and 15 miles to Auburn. It’s also a 20-minute walk on a single-track winding trail to a monument built into the side of the hill. It overlooks the vastness of the American River Canyon and the middle fork of the American River. It’s called “Barb’s Bench.”

Ten years ago today, Barbara Barsalou Schoener of Placerville was killed by a mountain lion as she ran alone on one of her favorite trail routes, an 18-mile journey that began at Auburn Lake Trails. She was the first person killed in California by a mountain lion in 85 years, and in the previous 1909 case the deaths were caused by rabies.

Schoener, 40, a wife, mother of two children, businesswoman and long-distance runner, had completed her first ultramarathon a month earlier, a rugged 50K event that included much of the same trail. She enjoyed the canyon’s serenity and beauty, often driving there from Placerville to run.

No one saw the mountain lion attack Schoener the morning of her fatal encounter. Authorities surmise the animal jumped her from behind. She fell down a slope, where the mountain lion launched its final attack and then buried her under debris.

Schoener’s husband, Pete, worried when his wife didn’t return home and he reported her missing. Search and rescue crews scoured the area that day, but didn’t find her.

The next morning, about a quarter-mile east of where the bench sets today, three veteran ultra-distance runners noticed a rubber visor and plastic water bottle oddly positioned down a steep embankment in secluded brush and a fallen tree. They investigated.

What they discovered were Schoener’s remains.

“In some ways, it almost would have been better if it had been somebody who killed Barbara, a homicide,” said Greg Soderlund, race director of the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run and Way Too Cool 50K, two popular endurance events held on the trail. “It would have been easier to understand.

“But it was worse that it was a cougar because it changed (things for) all for us. It really did. The innocence was gone. These animals could not only hurt you, they could kill you.”

Statewide, there have been 14 cougar attacks on humans, including six fatalities, since 1900, according to the California Department of Fish and Game. The latest death occurred last January in Orange County, when mountain biker Mark Reynolds was attacked while on a ride.

In each instance, the attack or death has prompted extensive media attention and passionate attempts to determine a reason.

Have humans encroached on mountain lions? Are the animals losing their fear of humans? Have there been more attacks since the passage of Proposition 117 in 1990, which designated mountain lions as “specially protected mammals”?

Moreover, has the increased awareness of mountain lions changed the habits of outdoors enthusiasts or those living in or near mountain lion habitat?

“I guess I am just not relaxed out there anymore,” said Pete Schoener, a decade after his wife’s death. “I’ll go elsewhere, even up by Carson Pass in the summertime. I will go and (run) 10 or 12 miles by myself. No problem. But if I go out to Cool, I’m just kind of turning my head all of the time. I hear little sounds. It’s not comfortable and it’s not enjoyable.”

Pete, who in 1990 completed the Western States 100 from Squaw Valley to Auburn, is now raising his and Barbara’s two active teenaged children. Both are sports-minded, but not as runners. They’ve been to their mother’s bench, but the family doesn’t discuss the tragedy often.

Yet, when friends ask to visit the memorial, Schoener will oblige.

“We go out there and sit and think about it,” he said. “I haven’t done it in awhile, but I have no problem with it. When my daughter was in second grade, we took out a small potted plant and left it there. Those kinds of things through the years make you feel better, but it’s still kind of hard.”

The bench was built by friends and aquaintances a month after Barbara’s death. They brought shovels and wheelbarrows, hauled in cement and chucks of granite, built several steps and the bench, and installed a plaque in her honor.

Today, there are potted plants, cultivated wildflowers, myriad trinkets and even a small, faded American flag draped across the monument.

For Kurt Fox of Meadow Vista, one of the runners who discovered the body, discussing the incident is still emotional.

He’s had sleepless nights and difficulty trying to understand what he and his friends, Ernie Flores and Russ Bravard, found. He credits counseling he received a year later while recovering from testicular cancer as very beneficial.

“My kids don’t go there,” said Fox, 42, a veteran ultramarathon runner. “I think it changed the actions of people for the first three years. But I still go out there by myself. I don’t know why. I still run by myself. After that, you’d think you’d be smarter than that.

“But I do know that I’ve passed women on the trails by themselves – a lot. I think some of it has to do with, ‘It’s not going to happen to me.’ And some of it has to do with not educating ourselves.

“We address it at our house and my wife now goes out with a dog and friends or at least one friend. But overall, I don’t think it’s changed much,” Fox said. “When I see the young women out there all I can think to myself is, ‘If you would have seen what I saw, you would take more concern about where your are.’ ”

Many experts believe the confrontations between cougars and humans are so unusual there’s not enough data to form theories or offer solutions.

“It’s a tough situation because these attacks are so rare and infrequent given the number of people who are out there,” said Steve Torres, a Department of Fish and Game wildlife ecologist. “There are theories that (mountain) lions are losing their fear of people. But my feeling about that is that there is more data to suggest that’s not true. They’re cryptic animals.

“I’ve been in this business long enough to know that theories and speculations are pervasive, and people are very passionate and opinionated about these issues,” Torres said. “But I think it’s important to recognize that they are speculations, and to point out to people that there are no easy answers and there are no solutions like hunting, for example, that would guarantee that there would be no more incidents.”

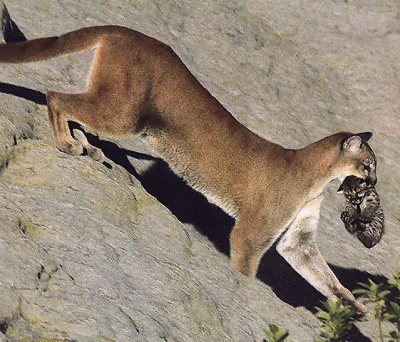

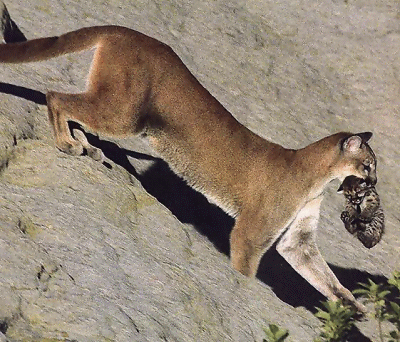

For a decade, including the time of Schoener’s death, Torres was the department’s statewide coordinator of mountain lion and bighorn sheep management. He was at the scene of Schoener’s attack and held the cub of the cougar identified as the killer, which was tracked down and destroyed.

“Certainly, there are more and more people in the outdoors, we know that,” he said. “But every time a mountain lion does cross that threshold of familiarity with people, it’s killed. That’s not contributing to the population, and it’s not contributing to genetics. So I think the arguments for mountain lions being more aggressive is kind of murky.

“Are they (mountain lions) indeed getting more used to people at a behavioral level where they lose their fear of them and something snaps and they can consider people prey? It’s an interesting hypothesis,” said Torres, “but still attacks are so rare that I don’t see that as something there’s any evidence for in California.”

Helen Hull of Sacramento has trained on the Sierra Nevada foothill trails for many years. She’s run more than 80 ultramarathons, including the Western States 100 four times.

“Barbara’s attack did change my comfort out on the trail, especially in that area,” she said. “I used to have no fear of running alone out there (but) I haven’t run that section of trail by myself since that happened. I still run on the trails alone sometimes, but it is often on my mind and I get spooked more easily.

“I rationalize that things I do every day are far more life-threatening, like driving and crossing busy streets,” she said. “I think knowing the person that this happened to makes it scarier. I have seen one cougar. I have seen lots of rattlesnakes, a few bears, and some scary people. But the thought of a cougar is what pops into my mind when I hear rustling in the bushes.”

Torres has heard similar tales. He can offer no solutions, comfort or understanding. But as a scientist, he does have an opinion.

“We definitely want to have some level of responsibility if we want to coexist with these animals,” he said. “It’s not to say that anyone would be at fault if (an attack) happened again. But it would be nice to know that people carried the educational message, so that we could potentially minimize the probability, as remote as it is.”

About the Writer

————————–

James Raia is the publisher of the free electronic newsletters Endurance Sports News and Tour de France Times, available on his Web site: www.byjamesraia.com. He can be reached via e-mail at james@byjamesraia.com.

Humans in the ecosystem tend not to perceive themselves as interdependent with the natural environment. Regardless, natural substances, derived from a diverse planetary flora and fauna, form the basis for much of our science, agriculture and industry. Natural systems contribute to the quality of the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the foods we consume. We turn to natural landscapes for recreation and renewal.

Humans in the ecosystem tend not to perceive themselves as interdependent with the natural environment. Regardless, natural substances, derived from a diverse planetary flora and fauna, form the basis for much of our science, agriculture and industry. Natural systems contribute to the quality of the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the foods we consume. We turn to natural landscapes for recreation and renewal.