Like most states, Idaho’s first lion management plan took the form of paying a bounty for every lion killed where the pelt was turned over to authorities. This program continued in Idaho until roughly fifty years ago.

Recreational Hunting

Idaho game officials don’t treat estimating the number of mountain lions currently residing within the state as a high priority. They have never put resources towards getting a handle on counting the state’s mountain lion population, which likely serves to their benefit as a population estimate would likely raise the possibility of public scrutiny and accompanying criticism if their annual hunting quotas were deemed excessive.

Back in 2008, Steve Nadeau, IDFG’s Large Carnivore Manager, made a presentation on the status of Idaho’s mountain lions at the Ninth Mountain Lion Workshop (a conference for state game managers). At that time he postulated that “given an estimated harvest rate statewide of approximately 15-20% (estimated to stabilize the population), we would back calculate and estimate a state population of about 2,000-3,000 lions.”

While that explanation may sound reasonable, what Mr. Nadeau is essentially saying is that since IDFG wants to believe (without the necessary scientific evidence to back that belief) that Idaho’s lion population is “stabilized” they simply took the number of lions killed during a particular hunting season, and arbitrarily assigned a 15 to 20 percent designator to that number which they then used to determine a mountain lion population total not borne out by robust data.

If IDFG were truly dedicated to managing Idaho’s mountain lions for sustainability, then they would first determine to the best of their ability (using scientifically accepted protocols such as habitat and prey availably, all mortality numbers and other research data) a defensible lion population estimate, and then use that number to set appropriate hunting levels to achieve a stable population.

Human-Caused Mountain Lion Mortalities in Idaho

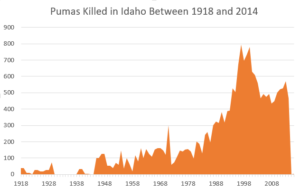

Since 1918 (the first year data is available) at least 18,276 mountain lions have been reported killed by humans in Idaho. Over 82 percent (approximately 15,000) of these mortalities occurred after mountain lions were classified as game animals in 1972. A few years back MLF researchers reviewed lion mortality data in eleven western states in an effort to determine where the highest concentrations of killings were taking place. During the ten-year study period (1992-2001), human-caused mountain lion mortalities steadily increased from 388 reported in 1992 to a peak of 796 in 1997 before steadying out and dropping slightly to 672 in 2001.

Based on MLF’s mortality density model, Idaho – with an annual average of 613 reported mountain lion deaths during this time period – averages 1.24 mountain lions reported killed by humans for every 100 square miles of habitat. The study average is 0.65. Using the study’s mortality ranking system, Idaho ranked 2nd among the 11 study states in reported human-caused mountain lion mortalities.

Idaho’s Mountain Lion Mortality Hot Spots

Using the study’s mortality ranking system, Idaho’s top five Mountain Lion Management Units (MLMU) were Palouse-Dworshak, Elk City, Panhandle, Oakley, and Lolo. The first four of these were also listed in the study’s ranking of the top 15 mountain lion mortality hot spots. Study-wide they rank 1st, 2nd, 8th, and 11th respectively.

From 1997 to 2001, these MLMUs accounted for 1,799 human-caused mountain lion mortalities. During this time period, these MLMUs were responsible for 50 percent of all human-caused mountain lion mortalities while encompassing only 30 percent of Idaho’s mountain lion habitat.

The Palouse-Dworshak MLMU was Idaho’s, as well as the West’s, number one killing field with an average mortality density rating of 3.2. From 1997 to 2001, the Palouse-Dworshak MLMU averaged 72 human-caused mountain lion mortalities per year and accounted for 10 percent of all the state’s human-caused mountain lion mortalities.

Mountain Lions and the Idaho Fish and Game Commission

Much of the attention on management of mountain lions in Idaho has centered on the Idaho Fish and Game Commission. Over the years, the Commission has been roundly criticized by conservationists, wildlife biologists, and even IDFG personnel, for politicizing decisions about conservation and management of mountain lions and other wildlife in the state. After retiring from IDFG in 2001, 29-year career veteran Conservation Officer Lee Frost lamented that “Right now, the commission is out of control on the predator issue. They, for whatever reason, have decided to manage for several species at the expense of predators. It’s not healthy for the department, the people or the resource.” The Commissions political decision making process, he argued, trumped and was frequently at odds with the conclusions of IDFG biologists. Notably, he stated that IDFG “hasn’t managed wildlife, per se. We’ve manipulated it. If we were managing it, we’d spend our money on improving habitat. We’re manipulating for revenue.” Frost lamented, “We’ve lost a lot of good people who won’t compromise good, sound science for politics.”

In 2002, IDFG director Ron Sando was forced to resign after he refused to retract citations given to a rancher who killed three mountain lions without apparent due cause. Sando stated in an email to IDFG employees that “philosophical differences have become impossible to overcome.” The day of his resignation, the Commission reopened the mountain lion season in eastern Idaho and increased the quota on female lions above those recommended by IDFG biologists.

Idaho Mountain Lions and Out-Of-State Influences

Criticisms of how mountain lions are managed in Idaho have not been confined to conservation groups and biologists. Fourth generation Idahoan and mountain lion hunter Ken Hoffman says he has observed a significant decline in mountain lions in the Garden Valley area of south-central Idaho largely because of too many hunters and inflated hunting quotas. “Now that running hounds is illegal in Washington, Oregon and California, there are literally hundreds of people who have moved here to run dogs on mountain lions and black bears,” says Hoffman. “There used to be about 100 people in our hound club. Now there’s over 300.” The increase in quotas, Hoffman argues, has been provided to satisfy the large number of outfitters in the area who provide mountain lion hunts to out-of-state hunters (An outfitter can average $3,000 to $5,000 dollars per person for an outfitted and guided mountain lion hunt).

On a side note: in the winter of 2011, Dan Richards, President of the California Fish and Game Commission accepted a free guided lion hunt in Idaho and posted a picture of him holding his “trophy” lion on the web. An outcry was made by enraged California citizens, and several members of the California legislature tried to get Mr. Richards to resign from the Commission. When he refused, several legislative bills were passed changing how California appoints members and elects officers to its game commission.

Mountain Lions and Idaho’s Elk Herds

In 2001, as a result of Idaho Fish and Game Commission directives, Wildlife Services, a program of the US Department of Agriculture, proposed to control mountain lions in the Clearwater Region of the state; ostensibly to see what effect it would have on elk populations. Widespread public opposition and threats of litigation by conservation groups stopped the project before it began. However, the reduction of the mountain lion population in this region was still undertaken by increasing the local hunting quotas. Faced with arguments that changes in habitat played a critical role in declining ungulate populations, then IDFG Wildlife Chief Steve Huffaker, stated “We don’t own or manage habitat. The only thing we can do something about is predation.”

Dr. Howard Quigley, who has studied mountain lions for several decades, argued that “When elk herds go down our immediate response is to go out and round up the usual suspects. Those tend to be the predators.” “Across the West, commissions are wrestling with this and really turning back some of the advances we’ve made in managing the cougars,” he adds. “There have been significant increases in hunting quotas, especially in those areas where deer and elk populations have declined.”

According to Lynn Fritchman, long-time Idaho resident, hunter, and conservationist, “While Idaho’s lion population is in no immediate danger of elimination, the excessively high quotas, in some cases no quotas, and lengthened seasons, based to a large extent on anecdotal evidence of predation on ungulates, does not bode well for the species. Habitat degradation and actual loss thereof are insufficiently considered when assessing declining elk herds.”

MOUNTAIN LION MORTALITIES IN IDAHO

1915 – 2011

| 1915 to 1958 — Bounty Period |

1,479 |

| 1959 to 1971 — Transition Era |

1,849 |

| 1972 to 2011 — IDFG’s Stewardship Period – The “Protected” Years |

14,948 |

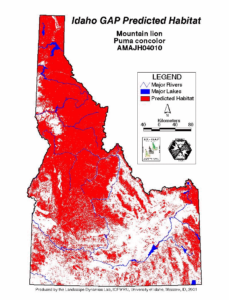

is potential mountain lion habitat. This habitat estimate might be excessive. Using a Gap habitat analysis map to ascertain the amount of mountain lion habitat in each of Idaho’s mountain lion management units (MLMUs), MLF researchers were only able to identify 49,314 square miles (127,722 square km) of potential lion habitat.

is potential mountain lion habitat. This habitat estimate might be excessive. Using a Gap habitat analysis map to ascertain the amount of mountain lion habitat in each of Idaho’s mountain lion management units (MLMUs), MLF researchers were only able to identify 49,314 square miles (127,722 square km) of potential lion habitat.