In Washington’s legal code, Puma concolor is generally referred to as “cougar.”

Species Status

The species is classified as a game animal, along with eastern cottontail, Nuttall’s cottontail, snowshoe hare, white-tailed jackrabbit, black-tailed jackrabbit, fox, black bear, raccoon, bobcat, Roosevelt and Rocky Mountain elk, mule deer, black-tailed deer, white-tailed deer, moose, pronghorn, mountain goat, California and Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, and bullfrogs. The species is further classified as big game, along with elk/wapiti, blacktail deer, mule deer, whitetail deer, moose, mountain goat, caribou, mountain sheep, pronghorn antelope, black bear, and grizzly bear.

Laws and regulations pertaining to Washington’s threatened and endangered species can be applied to mountain lions because any species native to Washington may be classified as threatened or endangered. However, mountain lions are not currently classified as threatened or endangered in Washington because the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission does not believe that mountain lions are seriously threatened with extinction throughout all or a significant portion of their range within the state.

State Law

Generally, treatment of wildlife in the State of Washington is governed by the Revised Code of Washington – the collection of all the laws passed by the Washington legislature. The state’s treatment of wildlife is also governed by the Washington Administrative Code – the collection of all the state’s agency rules. Since our summary below may not be completely up to date, you should be sure to review the most current law for the State of Washington.

You can check the statutes directly at a state-managed website.

These statutes are searchable. Be sure to use the name “cougar” to accomplish your searches.

The Legislature

The Washington State Legislature is the state’s bicameral legislative body. The lower chamber – the House of Representatives – is made up of 98 members who serve 2-year terms. The Democratic Party has controlled the Washington House of Representatives since 2002. The upper chamber – the Senate – consists of 49 members who serve 4-year terms. Washington maintains this website to help you locate your state legislators.

The Washington Constitution allows the state legislature to determine when it convenes. Washington law establishes the second Monday of January each year as the date the legislature convenes. The constitution limits regular sessions in odd-numbered years to 105 consecutive days. In even-numbered years, regular sessions are limited to 60 consecutive days. Special legislative sessions may be called by either the governor or by the vote of two-thirds of the members of each chamber. Special sessions are limited to 30 consecutive days.

Initiative and Referendum Processes

Washington allows its citizens to propose new laws through its initiative process and to repeal existing laws through its veto referendums. Washington initiatives are submitted to either the people or to the state legislature. Unlike some other states, Washington does not allow citizens to amend its constitution through initiatives. The initiative and referendum processes are created by Article II of the Washington Constitution, and they are governed by Chapter 29A.72 of the Revised Code of Washington. In order to be placed on the ballot or submitted to the legislature, proposed initiatives must gather valid voters’ signatures equal to 8% of the number of votes cast for the office of governor in the last gubernatorial election. Veto referendums require valid signatures equal to 4% of the last gubernatorial vote. In order to pass, an initiative must be approved by a simple majority – unless the initiative aims to authorize gambling or a lottery, in which case a 60% supermajority is required – and at least one-third of those voting in the election must have voted on the measure. Unless the initiative specifies a different date, an approved initiative goes into effect 30 days after the election.

Initiative 655

The Washington Bear-Baiting Act — submitted to voters as Initiative 655 — was approved by 62.99% of voters on November 5, 1996. The initiative classified baiting black bears and hunting black bears, mountain lions, bobcats, and lynxes with dogs as gross misdemeanors in the State of Washington. However, there have been many attempts to overturn Initiative 655 since it was passed.

State Regulation

Washington’s wildlife regulations are found in Title 232 of the Washington Administrative Code. The regulations are written by the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission.

Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission

The Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission is made up of nine members who serve 6-year terms. Members are appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Washington Senate. At least three commissioners must reside east of the Cascade Mountains and at least three must reside west of the Cascade Mountains. No two commissioners may reside in the same county. Law requires that all commissioners “have general knowledge of the habits and distribution of fish and wildlife” and prohibits them from holding any other office. When making appointments, the governor is to ensure the commission represents diverse viewpoints including sport fishers, commercial fishers, hunters, private landowners, and environmentalists. The commission’s main responsibilities are to set the state’s wildlife regulations and to oversee the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW)

The (WDFW) Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife enforces the state’s wildlife laws and policies. The department divides itself into separate wildlife and enforcement branches. The WDFW is a department within the Washington executive branch. The Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission oversees the WDFW’s activities.

Management Plan

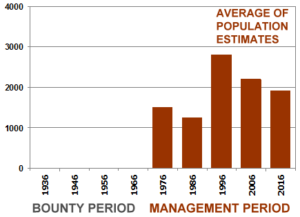

Washington’s latest mountain lion management plan is found in the state’s 2015-2021 Game Management Plan. The state’s plans for game management cover 6-year periods. The report is prompted by the WDFW’s legal mandate to “preserve, protect, perpetuate, and manage” the state’s wildlife. The plan is assembled by the WDFW Wildlife Program and guides the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission’s policy decisions.

Hunting Law

Hunting of mountain lions is allowed in the State of Washington. The regulations and laws governing “recreational” hunting of mountain lions specify 150 game management units organized into 6 regions. Mountain lion hunting season runs from September 1 to March 31.

Hound hunting is not allowed. However, the WDFW may allow the use of dogs during “public safety cougar removals.”

Washington allows the hunting of mountain lions with non-fully automatic firearms, centerfire cartridges greater than .22 caliber, shotguns 20 gauge or larger firing slugs or buckshot size #1 or larger, centerfire handguns with a minimum barrel length of four inches, crossbows with a draw weight greater than 125 pounds and a working trigger guard, and muzzleloading firearms .45 caliber or larger. Muzzleloading handguns used to hunt mountain lions may have one or two barrels, but both barrels must be rifled and be eight inches or longer. Mountain lions may also be hunted with long bows, recurve bows, and compound bows that produce at least 40 pounds of pull.

The Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission sets “harvest guidelines” for most of Washington’s game management units. Game management units may be closed to mountain lion hunting after January 1 if the unit’s harvest guideline is met or exceeded. Harvest guidelines are based on recommendations in Washington’s Game Management Plan. Washington prohibits the killing of spotted kittens and adult mountain lions accompanied by spotted kittens.

Public Safety Law

Washington policy allows a person to kill any mountain lion that is attacking a person or “posing an immediate threat of physical harm to a person.” Further policy states that the killing of a mountain lion in order to protect a person must be reported to the WDFW with 24 hours and the carcass must be surrendered to the WDFW or its designees.

Depredation Law

Depredation policy in Washington allows an owner to kill one mountain lion that is attacking livestock or domestic animals without a permit. A permit is required to kill any number of mountain lions that are damaging crops or to kill multiple mountain lions that are attacking livestock. Further policy allows the mountain lion carcass to be kept by the owner. There is a government-funded compensation program for owners who have worked with the WDFW to prevent depredation.

Trapping

Mountain lions may not be trapped for fur in Washington. Washington’s regulation governing trapping states that only furbearing animals may be trapped. The state does not include mountain lions on its list of furbearing animals. If a mountain lion is caught in a trap, it must be released unharmed. If the mountain lion cannot be released unharmed, the trapper is to notify the WDFW immediately. Intentionally trapping a mountain lion is a misdemeanor punishable by imprisonment of up to 90 days and a fine of up to $1,000.

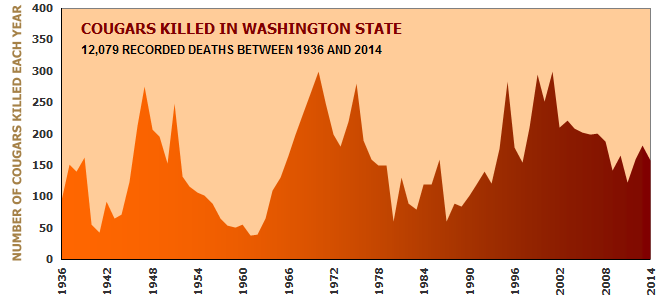

Poaching

Poaching law in the State of Washington provides some protection of mountain lions in law, but only as a deterrent. It is rare for penalties to be sufficiently harsh to keep poachers from poaching again. Hunting a mountain lion in any unlawful manner in Washington is generally classified as “unlawful hunting of big game in the second degree,” which is a gross misdemeanor. A gross misdemeanor is punishable by up to 364 days of imprisonment and a fine of up to $5,000. The WDFW will also revoke all the poacher’s existing licenses, tags, and permits, and suspend his/her hunting privileges for two years. A poacher is guilty of “unlawful hunting of big game in the first degree” if they possess three or more big game animals during the same “course of events” or if they are less than five years removed from a previous conviction for unlawful hunting of big game. Unlawful hunting of big game in the first degree is a class C felony punishable by imprisonment for up to five years and a fine of up to $10,000. Upon conviction, the WDFW will also suspend the poacher’s licenses, tags, and permits, and suspend his/her hunting privileges for ten years.

Road Mortalities

The Washington State Department of Transportation does not keep records of mountain lions killed on the State’s roads.

Captivity

Washington law generally bans the private possession of mountain lions. The law states, “A person shall not own, possess, keep, harbor, bring into the state, or have custody or control of a potentially dangerous wild animal,” and goes on to ban the breeding of potentially dangerous wild animals. Mountain lions are listed as potentially dangerous wild animals. This ban, however, does not apply to institutions authorized by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife to keep “deleterious exotic wildlife” (a designation that does not) include mountain lions), zoos accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, nonprofit animal protection organizations such as shelters, law enforcement officials in the course of enforcing wildlife laws, veterinary hospitals or clinics, authorized wildlife rehabilitators, wildlife sanctuaries, research facilities, circuses, anyone temporarily transporting potentially dangerous wild animals through the state, domesticated animals, anyone displaying wildlife at a fair approved by the Washington State Department of Agriculture, and game farms which may not possess mountain lions.

Mountain lions may be kept for rehabilitation purposes in the State of Washington. An individual wishing to rehabilitate mountain lions in the state must obtain both a general wildlife rehabilitation permit and a large-carnivore rehabilitation endorsement. The state’s regulation does not state what is required on the permit application but requires the applicant to demonstrate that he or she has completed at least six months or 1,000 hours of wildlife rehabilitation under the supervision of an authorized wildlife rehabilitator, provide the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife with a letter of recommendation from an authorized rehabilitator who agrees to advise the applicant, submit a written agreement signed by a veterinarian who agrees to serve as the applicant’s principal veterinarian, successfully complete the Washington General Wildlife Rehabilitation Examination, and have access to suitable rehabilitation facilities. Rehabilitation permits are valid for three years if not revoked sooner. In order to receive a large-carnivore rehabilitation endorsement , an applicant must demonstrate at least three months or 500 hours of experience rehabilitating and handling large carnivores (which are brown bear, black bear, cougar, wolf, bobcat, and lynx), show that he or she has been trained in large animal restrain techniques, submit to the department a letter of recommendation from a large carnivore rehabilitator who agrees to advise the applicant, successfully complete the state’s large carnivore rehabilitation examination, and possess approved rehabilitation facilities. Washington requires rehabilitation facilities to meet standards set by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association, and the International Wildlife Rehabilitators Council. Authorized state and federal agents may inspect rehabilitation facilities, records, equipment, and animals without prior announcement at any reasonable time. Rehabilitators must keep daily records and submit an annual report to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Daily records must include all wildlife acquisitions, transfers, admissions, releases, deaths, reason(s) for admission, nature of illness or injury, dates of disposition, and any tag or band numbers. Annual reports must be completed on the form provided by the department and be submitted before January 31 each year. Copies of the rehabilitator’s daily records from the year must be submitted along with his or her annual report.

Research

Mountain lion research is usually conducted in collaboration with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Researchers must obtain a scientific permit under conditions prescribed by the department’s director, but neither law nor regulation spells out the conditions. The applicant must demonstrate that he or she is qualified to undertake the proposed research and that the research is needed. The fee for a scientific permit is $12 and also requires an application fee of $100. Scientific permits are valid for the time specified on the permit unless they are revoked before expiration. There do not appear to be reporting requirements for researchers.