Experts debunk mountain lion myths

By Lori Stuenkel

San Jose – A recent mountain lion sighting reminded South County residents that with the summer heat and outdoor activities often come increased encounters between humans and the native predator.

Scientists say that mountain lions may be seen more often in the summer because people spend more time outside and in the mountain lion’s natural habitat.

But, they also caution, just because sightings may garner more attention following three fatal attacks last year, doesn’t mean there are more mountain lions in California or South County.

A handful of mountain lion experts, including scientists and game wardens, met with local media Wednesday to clear up what they called misperceptions about mountain lions, held by the general public and possibly spread through the media, that can cause unnecessary alarm.

“The evidence of any increase is based largely on perception,” said Rick Hopkins, a scientist who is creating a mountain lion conservation plan for a Southern California county.

No evidence of a mountain lion population increase exists, he said. In fact, there are likely fewer mountain lions today than there were 50 years ago.

As cities expand farther into hillside areas that mountain lions call home, however, encounters with humans are to be expected.

Mountain lions – also called cougars, pumas, or panthers – at one time were found across all of North America, but now exist only in the western states.

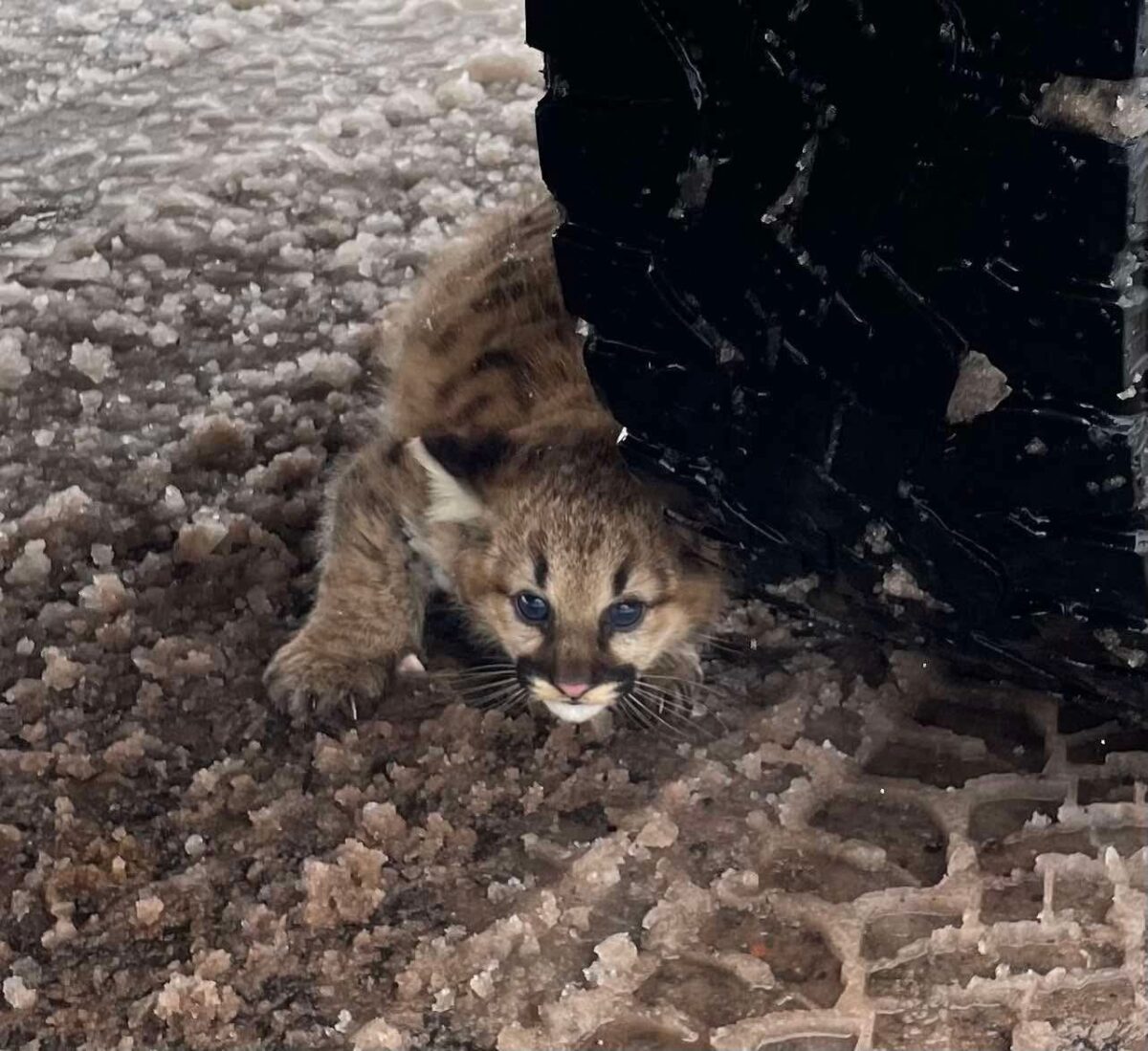

They are found throughout California, with the exception of the state’s central valley and eastern desert areas, and can be identified by their uniformly colored coat that ranges from tan to gray, and black-tipped ears and tails.

A mountain lion’s home range may span over 100 square miles for males, and 20 to 60 square miles for females.

Most of the mountain lions seen in rural neighborhoods in Santa Clara County are young males, said Capt. Dave Fox of the California Department of Fish and Game.

“They’re more vulnerable,” said Fox, a 24-year veteran with the department. “They get into trouble, kind of, they don’t make the best decisions.”

As mountain lion habitats shrink, they also are the first to be pushed by other dominant males into the less-desirable habitat bordering towns and cities.

When people encounter mountain lions roaming the neighborhood, there is little reason to panic, said Henry Coletto, Wildlife Deputy for the Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Office.

If most people and pets are indoors, the animal often can be frightened away – which it would rather do than encounter people.

“A mountain lion’s probably just as interested in getting the heck out of there as you are with it getting out of there,” said Doug Updike, a senior biologist with the DFG.

Unless the animal poses an imminent threat and is considered likely to attack a person, it is not considered a public safety risk.

Game officials prefer to let an animal run away on its own because tranquilization includes risks – even with a perfect shot, it can take five to 10 minutes to take effect – and attempting to re-locate an animal may put it in danger if it ends up in another male’s territory, said Steve Torres, senior biologist with the DFG.

The animal will be killed only in extreme circumstances, when it is likely to attack.

“Most people are worried about children, and they feel the department is reluctant to do anything about it until someone gets hurt,” Fox said. “But it’s based upon the law.”

Police who respond to a report of a mountain lion in a residential neighborhood often will err on the side of caution, he noted.

Although a cougar was spotted near a Morgan Hill elementary school last week, police tried to scare it away, and it eventually ran off unharmed.

The experts Wednesday also noted that mountain lion attacks are extremely rare. Since 1909, 13 people have been killed by mountain lions.

“If lions were really interested in us, we’d have a lot more incidents, and a lot more attacks,” Fox said.

How to minimize the risk of mountain lion attacks:

• Don’t hike alone. Go in groups, with adults supervising children.

• Keep children close to you. Lions seem drawn to children.

• Don’t approach a lion. Most will avoid confrontation, so give them a way to escape.

• Don’t run from a lion. Running may stimulate the lion’s instinct to chase. Face the animal and make eye contact.

• Don’t crouch down or bend over. People bent over look more like a lion’s pray. Pick up your children if a lion is nearby, but avoid bending over to do so.

• Do all you can to appear larger. Raise your arms, open your jacket, throw stones or branches if you can without crouching. Wave your arms slowly and speak in a firm, loud voice.

• Fight back if attacked. People have fought off lion attacks using sticks, clothing, tools, even their bare hands. Remain standing, as mountain lions usually try to bite the head or neck.

Report encounters or attacks to the Department of Fish and Game’s 24-hour dispatch center at (916) 445-0045.

Source: California Department of Fish and Game

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email