By Quinn Eastman, Staff Writer

NORTH COUNTY —- Mountain lions see people much more often than people see them, wildlife specialists say. Many of the times when Californians think they saw the stealthy cats, they were actually sighting a bobcat or a coyote, said Mike Puzzo, a biologist studying the movement of mountain lions in San Diego County.

“A mountain lion encounter will usually last about three seconds,” said Puzzo, who works with the UC Davis Wildlife Health Center. “Afterwards, all that you might see is the tail flashing away.”

High technology and careful observation are giving biologists a chance to catch up with the elusive cat.

Puzzo recently gave a presentation on his work in Lakeside to the San Diego Tracking Team, a group of volunteers that monitors wildlife around the county. He told the group that he and his colleagues have been learning more about how mountain lions use the terrain in San Diego County to find their favorite food, deer and avoid humans.

Most live in the mountain ranges in the eastern part of the county, but some venture west in search of food and territory.

The UC Davis biologists track mountain lions after forcing them up a tree with dogs or catching them in a remote-controlled cage. They then tranquilize the captured lion with an injection dart, have veterinarians examine it, and fit the cat with a radio-emitting collar. The signals from the collars allow the biologists to construct a map of the cats’ daily movements.

The area between Volcan Mountain and Scissors Crossing, east of Julian, is a major mountain lion corridor, according to Puzzo. In addition, his group has followed the movements of more than one lion into the Palomar Mountain area, he said.

He made a rough estimate that there are 90 mountain lions in San Diego County, out of between 4,000 and 6,000 in the state.

Walter Boyce, leader of the mountain lion study at the Wildlife Health Center, said his group would like to study more lions in North County with radio collars.

As North County communities continue to build houses and roads in what was previously backcountry, mountain lions are losing their hideouts, he said in a recent phone interview.

“We want to find out how they move across a landscape that’s increasingly dominated by people,” Boyce said.

For example, Boyce said, mountain lions probably cross under Interstate 15, perhaps at underpasses around Temecula Creek, he said.

Figuring out exactly where and when they do can guide conservation groups in their efforts to preserve land. It can also help people protect themselves and their pets, he said.

The UC Davis biologists know the most about lion traffic in the area around Cuyamaca Rancho State Park and Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. Before the devastating Cedar fire in 2003, about eight lions used some part of the Cuyamaca park, but not all at the same time, Boyce said.

More recently, the researchers have identified six lions intermittently using parts of Cuyamaca.

Adolescent upheaval

Mountain lions usually have stable territories, but upheaval sometimes takes place when an adolescent male strikes out on its own and establishes its own turf, wildlife specialists have found.

Mountain lions can live as long as 12 years. Before male lions reach sexual maturity at around 2 years of age, they can move up to 100 miles away from their usual haunts to find new ground.

“There’s a lot of pushing and shoving for territory among the male cats,” Boyce said.

Mature males can have a territory of 200 square miles, and females use between 50 and 80 square miles, he said.

One older male lion was recently detected roaming from Pine Valley near Interstate 8 all the way to Palomar Mountain and the Riverside County line.

Boyce hypothesized that the older male, called M17, was kicked out of its usual territory by younger males who were competing for dominance.

A threat to pets, not humans

Mountain lion attacks on humans are extremely rare. State Department of Fish and Game records show there have been just 15 attacks on people since 1890, six of them fatal.

The department reports hundreds of sightings every year, but less than 3 percent are deemed threats to public safety.

However, a greater threat exists to livestock and domestic animals. Most lions will kill a domestic animal at some point in their lives, especially in California, the Davis researchers suggested.

Mountain lions are protected by law in California, and can only be killed if they present a threat to public safety or to domesticated animals, and a permit from the Department of Fish and Game is required.

In 2004, the department issued 231 permits statewide, leading to 115 lions being killed.

Lions also often die from being hit by cars and disease, and sometimes after fights with each other, the Davis biologists found.

Puzzo and Boyce both emphasized the need for backcountry dwellers to protect their pets at night by bringing them indoors. Mountain lions are mostly active at dusk or at night.

A fence will not protect a pet because lions can jump 15 feet, they said. Outdoor lighting and removing dense vegetation can also contribute to safety.

After they kill deer, lions sometimes bury the partially eaten carcass to protect it from decay and come back later to feed. If backcountry property owners discover a cache, the Department of Fish and Game advises them to drag it a few hundred yards away.

Closer in

Other researchers have spotted mountain lions in North County using more indirect methods than radio collars.

In what park wildlife specialist Annie Ransom called “a very lucky shot,” a San Diego Tracking Team remote camera spotted a mountain lion in October in Poway’s Blue Sky Ecological Reserve.

In addition, a recent 18-month San Diego County-sponsored study of wildlife traffic around Wildcat Canyon Road in Lakeside found persistent signs of a female lion behind the Barona resort’s golf course, as recently as May.

It’s not clear whether the female was ever seen by humans, said Wendy Orth, at the county’s Environmental Services program. Most of the evidence for her presence was from tracks and scat, she said.

Rangers at Daley Ranch, the Escondido-owned wild land preserve at the north edge of the city, have been wondering if the recent construction of wildlife tunnels under Valley Center Road will mean more mountain lion traffic into the area.

Evidence exists for past mountain lion traffic between Daley Ranch and the rugged area around Lake Wohlford.

According to park ranger Duane Boney, four mountain lions were killed by motorists between 1997 and 2002 near Valley Center Road. The deaths occurred in a tight area close to Stanley Peak, on the west side of the road, and the Escondido police shooting range, on the east side.

“There might not be more moving through, but maybe fewer will be killed now that there are tunnels for them to use,” Boney said.

To help avoid a mountain lion attack:

Hike in groups, and stick close together.

Keep children close to adults.

Talk as you move along a trail.

Take note of unusual bird or wildlife activity.

If you encounter a mountain lion, avoid arousing their predatory instincts:

Do not run or turn your back on the animal.

Do not crouch down or bend over.

Pick up young children.

Raise your arms and try to appear large.

Speak firmly in a loud, deep voice.

Source: California Department of Fish and Game

More facts

Male cats measure 8 feet long and weigh 130 to 150 pounds.

Female cats measure 7 feet long and weigh 65 to 90 pounds.

Cats live up to 12 years in the wild and 25 years in captivity.

Mountain lions were pursued by bounty hunters in California in the 1920s.

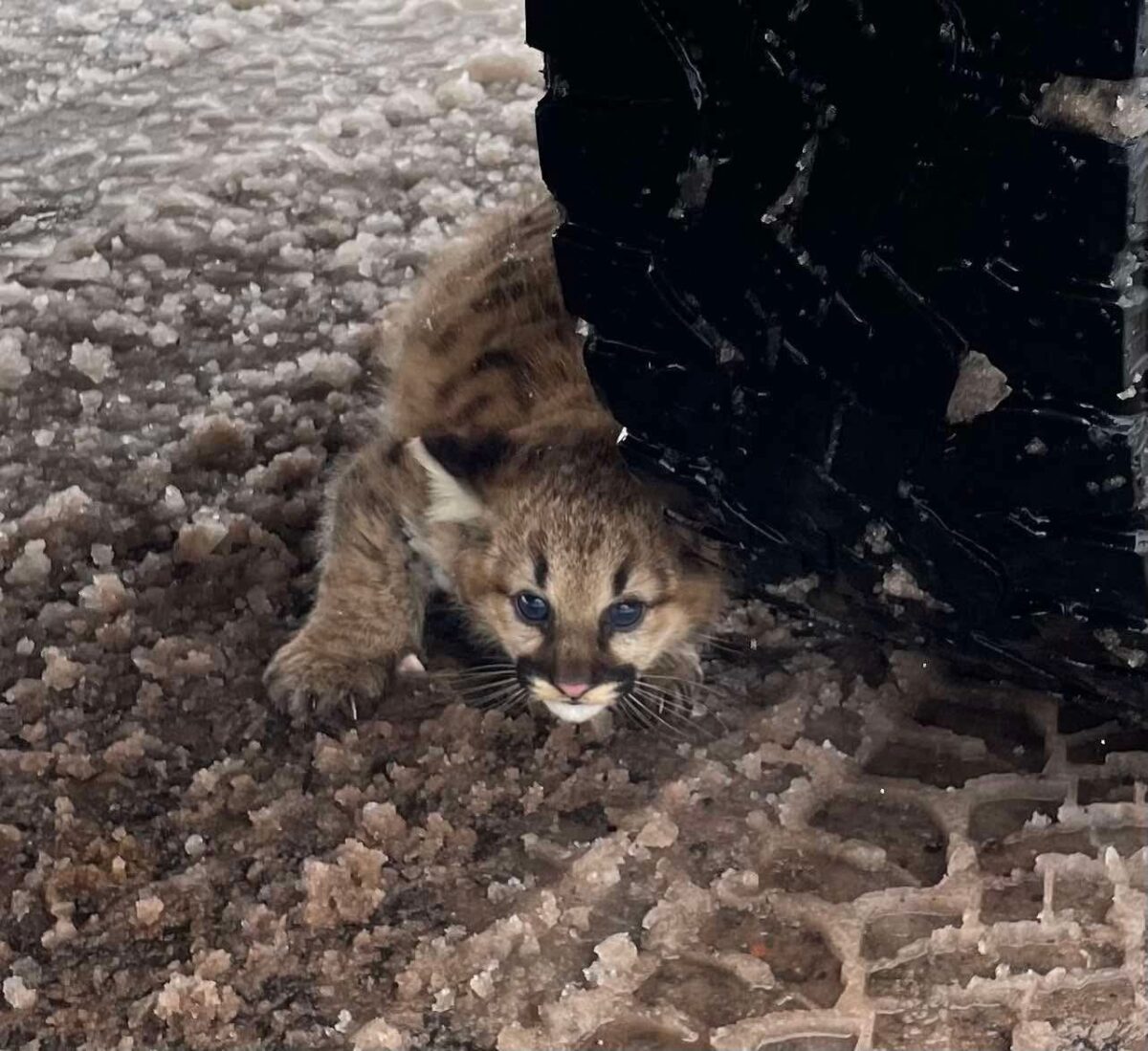

Lion cubs are covered with black/brown spots and have dark rings around their tails. The markings fade as they mature.

They bury their food and come back to the cache.

Contact staff writer Quinn Eastman at (760) 740-5412 or qeastman@nctimes.com.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email