ON AIR: Geneticist Ashwin Naidu Uses Forensics to Study Predator and Prey Interaction

An Audio Interview with Craig Fergus, MLF Volunteer

Listen Now!

Listen Now!

Listen to the interview from MLF’s ON AIR program, podcasting research and policy discussions about the issues that face the American lion.

It’s a messy job. Ashwin specializes in extracting DNA from scat — fecal samples — and he has discovered a great deal about the size and behavior of mountain lions in this region. Lions have been blamed for declines in bighorn sheep populations in Kofa National Wildlife Refuge, and management officials are considering proposals to completely wipe out predator populations. Now more than ever, Ashwin’s research is critical in helping us better understand the species and promote ecological conservation.

Transcript of Interview

Craig: Hello, Ashwin. Welcome to On the Air, and thank you for taking the time to talk to us today.

Ashwin: Thank you, Craig. I’m really excited about this program you have initiated and thank you, Amy, for bringing me in touch with Craig with the Mountain Lion Foundation, for interviewing me about my research and projects as they relate to mountain lion management in Arizona.

Craig: No Problem. So as you mentioned earlier you’re involved in some mountain lion projects down in Arizona. Why don’t you give us a run-down of the work you’re currently involved in.

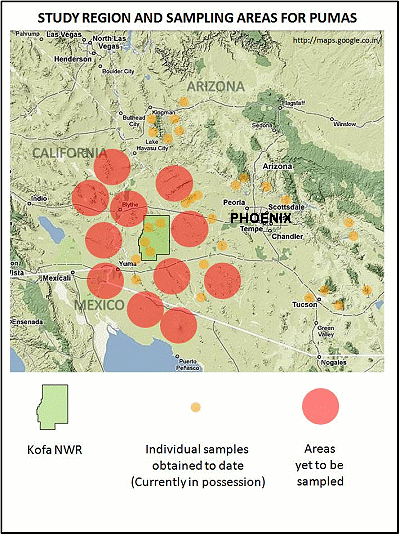

Ashwin: Yes, most certainly. I am originally – I was in India, and I’m from India. I got in touch with Dr. Melanie Culver from the University of Arizona at a conference in Oxford about felid biology and conservation. Melanie put me in touch with a project on trying to document mountain lion populations and studying their diet in southwestern Arizona, particularly to identify presence of mountain lions in the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge and extending to the mountain ranges that surround Kofa National Wildlife Refuge in southwest Arizona.

My expertise lies primarily in the use of genetics for wildlife conservation, conservation genetics and wildlife forensics, particularly dealing with DNA. So when I was put in touch with this project with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service, my objectives were to document the minimum number of mountain lions in Kofa National Wildlife Refuge and surrounding areas and what their diet profiles were.

The project was initiated due to concern that was floating among managers and scientists in the area as it related to bighorn sheep populations. Desert bighorn sheep populations declined by fifty percent in the area over the last ten years, 2002 to 2008.

There are many reasons why Fish and Wildlife Service and Arizona Game and Fish began taking interest into investigating mountain lions in this area because a decline of such a great extent was probably due to predation by mountain lions. It was also speculated and is still under the process of investigation, trying to identify the causes of that decline, particularly related with habitat; whether it was water, drought, or was it due to hunting or disease. There are several factors that both the Arizona Game and Fish Department and the Fish and Wildlife Service were interested in to investigate the decline in bighorn sheep. Since predation is a primary concern.

Craig: That’s great coverage on how you’ve come to work on this. How about you tell us more about using scat as a way of detecting mountain lions and how you can use that information to both look at how many there are and what they’ve been eating.

Ashwin: Yes. Non-invasive genetics, particularly the use of fecal samples to document population size and diet, has become very popular in the recent past because of improvements in genetic techniques on obtaining DNA from fecal samples and the analysis and identification of species, sex, individuals, and diet.

How I went about this was to collect scat in the first place from the refuge in the surrounding mountain ranges in southwestern Arizona. What I did was I extracted DNA from the scats that were collected and identified species.

We extract the DNA and identified the species from the surface of the scat, the DNA from the surface, and that told us, “Ok, these feces samples belong to mountain lions.” We also identified some other species like bobcats and coyotes. But, morphologically, when you identify scats in the field sometimes you’re not sure what animal species it is, but then when you actually extract DNA, and you sequence the DNA, you are sure about the species identity.

Once we identify the species, each species will then be analyzed separately. If I had a bunch of mountain lion scats, I would go ahead and open up those mountain lion scats and pull out bone fragments or specific tissue remains from prey species that the mountain lion ate.

The same technique of this species identification that I applied to identify the scat, I would apply to identify the prey remains that are found from the scats. Once we get DNA from the prey remains that are found in the scat, we would identify the species of what prey remains are present — prey species are present — as part of mountain lion diet. So when you collect a lot of samples in a certain area and you repeat these techniques — this technique of species identification on scats from a large area — then you have a good sample size.

When I documented prey, I was able to generate a diet profile for the mountain lions in the area. Most of mountain lion diet that I documented was comprised of mule deer and bighorn sheep. A good percentage, about 30 percent, was composed of smaller prey items like the American badger, grey fox, and also domestic sheep, which is both fascinating and bothersome and lead to further questions about what these lions are eating on the refuge. That is the procedure on how we identify their diet and how we identify species.

Once we have that, we were also interested in the questions like I mentioned earlier; of estimating population size, how many individuals there are, and what are their sex. I use the same techniques that exist for other large carnivores, particularly wild felids to document the number of individuals.

What I did was a technique that we all know called DNA finger printing. We use these short repeats on DNA sequences called micro-satellite markers to generate unique genotypes or DNA fingerprints for each of these individuals.

Since each individual has its own unique genetic profile, we would know how many individuals there are. If from two different scats that we collected separately at different times, we get the same profile, we would know that it is the same individual. That way we would compare the number of unique genotypes to the number of scats collected. Over time we would come up with an estimate of the minimum number of individuals that are in a given area where we sampled. One other thing is the technique of sex identification. Once you identify individuals, we were interested in knowing, “Ok, what are the sexes of these individual lions?” We used another technique that was designed particularly for felids and felid sex identification, and to our surprise it did work really well on identifying sexes of these individuals.

We could identify from the minimum number of eleven individuals that I identified in this area, we could identify sexes of nine individuals. We found six males and three females. This sex identification assay is based on the X and the Y chromosomes. If it was a female, we would get an amplification only for the X chromosome and from our assay or genetic technique we would know that it is a female. And if it was a male, we would know that it was a male because we would get two amplifications, one for the X and one for the Y, and we would know that it’s a male. On that basis we can distinguish between males and females from scats in the given area.

So just to summarize, in my project I documented the minimum number of lions, what their sexes are, and also their diet. And not just mountain lions, but also bobcats.

Craig: Fantastic. That’s really interesting. A lot of different methods that could potentially be used for mountain lion research. Now, what do you think are the main things that we could pull from this data and how can they be pushed into management applications?

Ashwin: Sure. When referring to this particular area I’m working in, previously there was little or no information about mountain lions in the area. Mountain lions were considered transient, and the first mountain lion was documented in 2003 only after the last record in 1944 of a hunter killed mountain lion in Kofa.

Once U.S. Fish and Wildlife service and [Arizona] Game and Fish started documenting mountain lions, they took up a project, a camera-trapping project, and placed cameras throughout Kofa National Wildlife Refuge. One of my co-authors, and also the person who wrote the grant for my project, Lindsey Smythe, documented five different mountain lions in the area.

Mountain lions are difficult to identify using camera traps because, unlike other cat species or wild felid species, they have very few markings on their bodies that we can use to distinguish between individuals.

The Fish and Wildlife Service and State Game and Fish Department wanted to go a step further and try to use other techniques to append to their current investigative techniques, and genetics was their next best thought. Once we used genetics, we found so much more – we learned so much more about the mountain lions in this area.

Not only did we find eleven individuals in the Kofa, we also found two more individuals in the surrounding mountain ranges over the last three years of scat collection. We also complimented the diet data, and we now know that mountain lions, what their diet profile is in this area and what they’re eating.

Although we did not come up with a conclusive predation rate of mountain lions on bighorn sheep and mule deer in the area, we now know some information about their diet and how we can proceed now with the available techniques at hand; camera trapping, GPS, radio collaring, non-invasive scat genetics, and aerial surveys of prey species. When we put all of these together, our hope is that we can come up with what has been the causal factor for the decline in bighorn sheep.

When we map all of this information on a timeline, we would be able better to predict what might happen in the future with this population and how mountain lions are moving across the landscape as they were previously not studied. We do not know much information about that and now we know so much more. So although nothing is very conclusive at this point, I’d like to say that it did help us better ground management decisions in the area.

Craig: So that leads right into my next question. What’s next for you, what’s next for the project and what research can we expect to see in the near future?

Ashwin: Yes, I’m very exited with the new research, particularly from the genetics aspect because we are moving toward trying to understand the landscape genetics of mountain lions in the area.

We recently had a new student working in the lab on developing a single nucleotide polymorphism chip, what we call a SNiP chip, for mountain lions. What we can do with this SNiP chip is it allows us to look at a genome wide. When you look at mountain lion genetics, and you do relatedness analysis, previously we were looking at only certain parts of the genome. Now we will be able to look at it at a higher resolution.

What we would like to answer in the first stage of questions: if mountain lions were not in this area before but they were only transients and now they’re showing signs of residency, we’d like to know where these mountain lions are coming from. And, also be able to see if mountain lions are adapting.

So once we have this SNiP chip available, we’ll be able to look at certain locations on the genome that are locations that tell us about adaptation, and there are certain locations on the genome that tell us about what are neutral, and we could use those for relatedness estimates.

If you map relatedness of mountain lions across a landscape, we could predict or we could visualize what is the gene flow among mountain lions across the landscape. When we combine GIS tools with this genetic data, we could be able to predict mountain lion movements across the landscape.

One of the questions that I wish to answer during my Ph.D. dissertation is at this small scale and large scale, what is the general movement pattern of mountain lions? We would be able to predict that using genetics.

The small scale I’m talking about, southwest Arizona, where more regionally the Fish and Wildlife Service Management agencies and Arizona Game and Fish would like to know where the mountain lions from Kofa came in from. At the larger scale from a research standpoint we would like to understand, if mountain lions did re-colonize North America, which routes did they take to re-colonize?

This will all be dependant upon collaborations from several different agencies and individuals interested in mountain lion research region wide. Maybe in the future, given the GIS tools, we could come up with predictive models on mountain lion movements and habitat-based models that would tell us which landscapes mountain lions would colonize next. So that is very exiting to us.

Craig: Those all sound like really exciting conclusions to be found if that work goes well. What would be the best way to keep up with your research? Is there a website people can follow you at?

Ashwin: Sure. I have the Cat Specialist Group web site that has posted a brief description about my masters project and my Ph.D. dissertation, but that is about my projects with the Arizona Game and Fish, and Fish and Wildlife Service. But I would like to say that once we have this puma SNiP chip, it would be a universal use resource.

As mountain lion researchers make use of genetics more and more, we will be able to come up with databases of mountain lions like we are doing with humans all across the range and also their diets. We would be moving towards understanding predator-prey population dynamics with this data that we will be collecting. Also we will be learning about adaptation of mountain lions.

My hope is that we will be able to predict, given the data that we collect from now on and about ten years from now, about what will be the outcome and the effects of landscape modifications by humans on mountain lion populations at a larger scale which is across North and South America and how it would affect their genetic diversity.

Craig: Well that answers just about all my questions. Is there anything else you wanted to say before we finished up?

Ashwin: I’d like to say that Mountain Lion Foundation is doing a great job with making people aware of not just mountain lions but also their prey and their habitat. When you look at large charismatic carnivore from a top-down approach, you are presenting an umbrella of life to people and how large carnivores can help maintain ecological processes.

There has been a lot of literature published on trophic cascades and how if we focus our efforts on these large carnivores or large predators and species that are on the top of the ecological pyramid, we would be able to look at everything that is operating under this umbrella as one single unit.

I think from a philosophical perspective it is very important to conserve ecological processes as a whole. Studying large predators helps cover a very good percentage of trying to understand these ecological processes. Thank you very much to have taken this initiative, to interview researchers, and to bring everyone together in this new digital age.

Craig: (laugh) Well, we definitely like to do our part. Thank you very much for your support and for coming to talk with us today.

Ashwin: Sure. Thank you very much, Craig. I’d like to say thanks to Amy as well for getting us in touch once again.

Craig: Great! Well, again, thank you very much, and I hope folks keep checking back here for more interviews with fantastic researchers like Ashwin here. Thanks so much for listening.

Ashwin: Thank you, Craig.

Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for noncommercial use.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email