ON AIR: Kim Vacariu on Conserving Continental Corridors

11/25/10 An Audio Interview with Julie West, MLF Broadcaster

Listen Now!

Listen Now!

Listen to the interview from MLF’s ON AIR program, podcasting research and policy discussions about the issues that face the American lion.

Transcript of Interview

Intro: [music] Welcome to On Air with the Mountain Lion Foundation, broadcasting research and policy discussions to understand the issues that face the American lion.

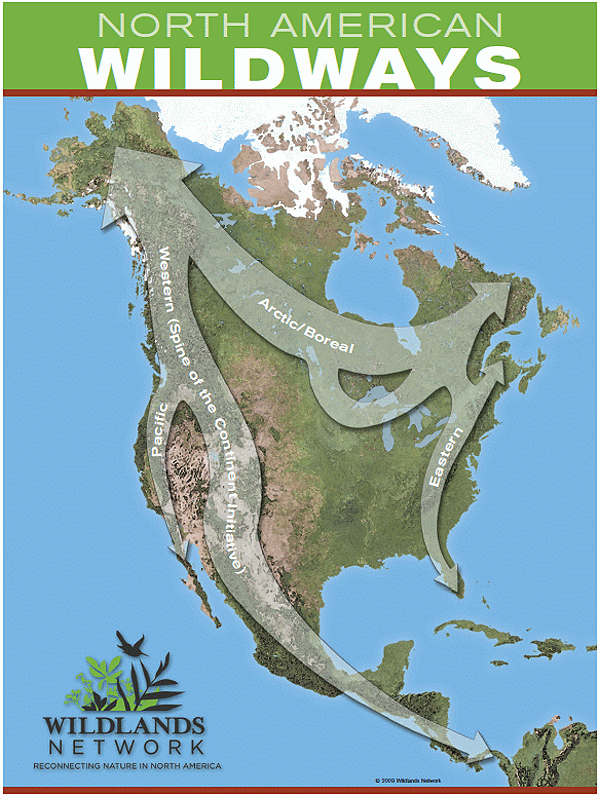

Julie: Hello, I’m Julie West. Today’s guest is Kim Vacariu. Kim is the western director for Wildlands Network, an international conservation group working to establish a system of connected wildlands across North America. Kim is currently working with a broad range of conversation groups, state and federal agencies, and other stake holders, to protect and connect wildlife corridors along the 5,000 mile Western Wildway that stretches from Alaska to Northern Mexico. Kim works from the Wildlands Network’s field office in Portal Arizona. Welcome, Kim.

Kim: Well, thank you.

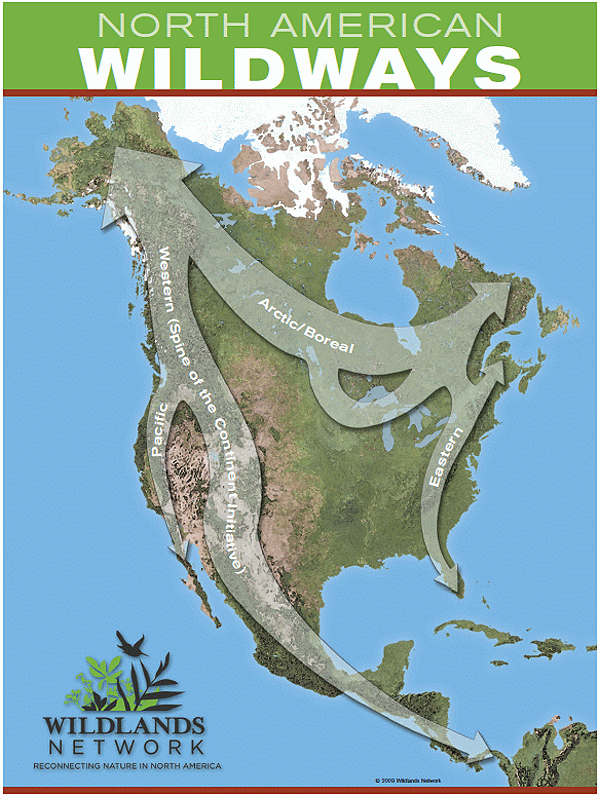

Julie: Now, I know that there are actually four continental Wildways slated for protection that comprise this project. So I thought you could briefly speak to each, so we have a sense of scope and better know the purpose of wildlands.

Kim: Sure, well you’re right there are four, and I guess if we look at the continent of North America from space you can kind of picture that maybe across the Northern areas of Canada, the boreal forest areas we have one wildway that stretches from the West to the East across those boreal forest and ends up in the Maritimes of Eastern Canada.

Another, then starting from the western coast of the U.S., we have what we call the Pacific Wildway. And that stretches from Alaska to Baja, pretty much along the West Coast.

The third wildway is the one that I’m actually involved with quite a bit. And that’s the Western Wildway. It stretches from the Brooks range in northern Alaska all the way south along the Rocky Mountain range and associated mountain regions all the way to the Sierra Madre Occidental in northern Mexico. And as you mentioned, that’s about 5000 miles.

And finally we have an Eastern Wildway, which again stretches from the Maritimes of Canada in the Northeast, all the way along the Appalachian Mountain chain and southeastern coastal plains through Florida, to the tip of Florida. So those are pretty massive and vast landscape areas that we hope to, over a fair amount of time, begin to protect and connect.

Julie: Right. Quite a project! Tell me how you begin to identify which areas should comprise the various zones.

Kim: Well we, I’ll speak to the Western Wildway since that’s the one that we’ve actually made the most progress on and completed some work on. But essentially, what we’ve done is look at the landscape from the thirty-thousand-foot level. And then break that down into what we call wildlands network designs, which are essentially conservation plans that cover regions within those broader wildways. For example, in my area, which is southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, we have created what we call the Sky Island Wildlands Network Design.

Of course, that’s named after the mountainous region that encompasses this area. And we then begin to work with partners on a very high level to determine what types of planning has already occurred within the regions that we’re most interested in. And in fact it’s our partners who really give us the real foundation for beginning these mapping processes.

For example, wolves and bears would be two good examples of wide-ranging species that we focus on, and clearly the idea behind that being keystone species. These are the ones that if we protect their habitats and their movement pathways, we’re relatively assured of being able to protect habitat for multiple numbers of other species.

Julie: Okay. So, genetic diversification of a species is one important outcome. I know that. When you increase the range, you increase the territory. They can better mate. They can better roam. So is this an example of how the mountain lions, for example, can potentially benefit from this project?

Kim: It absolutely is. Mountain lions, of course, fit that category: keystone species. And even though we wouldn’t expect an individual mountain lion, say, to range all the way from Alaska to Mexico, we do know that they range hundreds of miles. And so the idea behind overlapping conservation regional plans would be to allow those mountain lions’ ranges or habitat areas for specific animals to overlap with one another. So that an animal, say, in the Sky Islands region would ultimately have a way to interact and mate with an animal from a more northerly region.

Julie: Right.

Kim: And therefore, genetic viability is increased.

Julie: Well, let’s back up. You were talking about partners. It seems like your partners are both scientists and conservationists. And people actually, as you say, are working to identify these core areas that should be protected. And they bring that reasoning with them. But then, the second group of partners really does seem like whoever’s on the ground, who are the ranchers, who are the private homeowners. How do you get those people on board with a project like this?

Kim: Well, it’s been challenging, quite frankly. And the reason it has been challenging is because we are talking very large landscapes. And Wildlands Network has essentially pioneered this concept of looking on a continental scale at conservation. And so we are learning, of course, as we go along. And when we want to involve tribal land owners in particular who are critical to making these plans viable and at the same token we also have other land managers that are very important to us. Maybe we can get to those later. Those would be the public managers.

But as far as private landowners, we work very closely with land trusts to make sure that private land owners have the information they need to make decisions when they are considering development of their properties. As you know, ranching is not a very high profit industry at this time. And economic pressures, especially now, are really coming down on ranchers to be able to figure out ways to continue on the land without completely selling off their homestead.

And so we do things like create conservation planning workshops for private landowners, in which we bring in land trusts and other, actually other federal agencies that offer dollars to private landowners to conserve their properties. Which ultimately results in cash-in-hand for them, and hopefully would help them to stay on the land and to refrain from development.

Julie: Okay. So, some cash incentive but also the incentive to keep their land out of the hands of developers and have it be the land they love that’s free and undeveloped, where maybe cattle can range. How do you convince them that, aside from the cash incentive, that… how do you get them to be carnivore friendly, I guess, is the phrase I’m looking for?

Kim: Right. Well, that’s the big, that’s the big challenge. And we’ve actually found that we’re having success in that area, recently. And in fact, we’ve really noted that many very large landowners are actually interested in conservation. There’s so much more information available these days to land managers regarding the effects of having native predators on their property versus eliminating those predators.

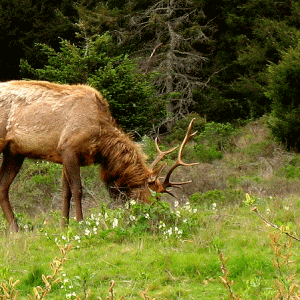

And I’ll just give you one quick example. In Colorado, we are working with a very large ranch owner who noticed that many of his aspen trees were in decline. And one of the income sources on his ranch is eco-tourism, and also hunting. And he wanted to make sure that the people that visit his ranch have a very positive visual experience of the Colorado Rockies etcetera. So he set out to try to determine why the aspens were in decline. And a current study is under way there that Wildlands Network is helping to fund, that will set sort of a long-term biological assessment of the land to see whether or not the populations of elk on that property are, in fact, impacting the aspen decline.

Julie: Like in Yellowstone?

Kim: Exactly in Yellowstone. And of course there are no wolves, for example, in that area at this time. Although there is some evidence that there may be a few naturally recolonizing there. So that adds a little bit more interest to the project. And so that’s an example of a rancher who’s actually looking at the science of conservation biology to improve his income potential.

Julie: Because the wolves come in, they are preying on elk who can’t lollygag about the eating, haha, eating the young aspens. And so the aspens and other riparian plants have a better shot of growing because the wolf is now keeping that in check. Is that how it works?

Kim: That would be how it would work. And you know, there are varying levels of that. There are many studies that have occurred in Yellowstone that have actually pointed to the fact that in the presence of wolves, obviously, keeps elk moving.

Julie: Right.

Kim: And therefore, keeps them, essentially, out of the riparian areas. And therefore allowing saplings to develop that haven’t been developing there due to over-browsing by elk.

Julie: Mm-hm. And is there a similar anecdote you could share related to mountain lions?

Kim: I’m not so certain that I have an exact anecdote for mountain lions. Although clearly, mountain lion prey is similar to that of wolves. And one would assume that the same types of ecological effects could be associated with the presence of mountain lions.

Julie: Mm-hm. And it does seem that you’re not only encouraging, yes, by encouraging the predators and particular wildlife to occupy land you’re encouraging certain kind of plant to thrive. And it seems that there’s a whole cascade effect.

Kim: No question about that. In fact, these trophic cascades as they’re called, are really becoming a centerpiece to the science of conservation. Well they have been a centerpiece to the science of conservation biology.

And you know, it all really started with the work that was done in Yellowstone which to just follow through with that cascade — when wolves were removed elk populations exploded — as we said. And they began to browse all the new seedlings and saplings that were growing in riparian areas.

And the next step in that cascade was that beavers were reduced in numbers, so therefore there was less beaver damming activity. And, due to less beaver damming activity, there was less fish population. And as you can see, that goes on and on. And, of course bird populations and many other types of species were of ultimately affected by that.

Julie: So, some of these workshops you offer to the ranchers again, getting back to them, get into this kind of detail and help them see how they’re contributing to the health of an ecosystem?

Kim: Absolutely yes. That’s one of the main goals of this. Because in order to encourage a private land owner to take actions like these to protect land, they clearly have to have some basis for doing so. And ultimately when you can connect these actions back to increase income, that’s when you begin to develop an audience. And that is slowly happening. And we’re real excited about that. And we expect that we’re gonna be able to move that trend forward in the next uh, short amount of time.

Julie: Okay. And then, I’m just wanting a better sense of how it works. I’m sure you’re working with GPS, you mentioned that, and sophisticated maps. But also scientists. So, someone might note, oh here’s a five mile corridor in this wetlands area that’s really key for, you know, the survival of these certain keystone species, but it’s currently being occupied by X, Y, and Z families. Then do you have someone who will literally approach those families if they’re not already being involved in these workshops or how do you get them?

Kim: Yeah, in some cases that’s the way it works. Typically, it’s a long-term process. And, just like anything else where you’re trying to attempt to create change.

Julie: Mm-hm.

Kim: You’ve got to move slowly. And, you’ve got to make the appropriate opportunities for this to occur.

Julie: Right. Right.

Kim: And that’s one of the reasons that we create these private landowner workshops, so that multiple private landowners can attend at the same time. And therefore they feel the safety of being with their neighbors and with the understanding of the problems that they’re all facing and it makes the concept of a multiple attended workshop a little better.

Julie: Right, right. And that they’re all stewards, or they can help in this greater stewarding project.

Kim: Yes. Another important aspect of that is making sure that the messengers are correct. In many of these cases we will invite a rancher who we know has already committed to conservation to lead some of the discussions in these private landowner workshops. So that also helps to create a sense of ease amongst participants.

Julie: That’s a great idea. So what are some of the core issues at stake for your area, Kim? Are there any…

Kim: Well, we of course are right on the US-Mexico border. And it, I’m sure that all you have to do is pay attention to one or two days worth of news before you actually begin to realize that the security infrastructure that’s being implemented along the border may have some purposes that it achieves regarding immigration. But at the same time, there’s a very large impact on wildlife corridors that cross the border.

Julie: Sure.

Kim: And, so that’s one of the big issues that we’re facing: how to elevate the concept that we need to have some ecological concern regarding these infrastructure projects, as well as security concerns.

Julie: Is it possible to infiltrate some of those other discussions so that they’re on the table while the other issues are being considered?

Kim: Well, it is. And we’ve over the past ah, about three years, we’ve conducted a number of symposiums that include private landowners and public land managers and the border patrol and Department of Homeland Security Officials. Symposiums at which they are exposed to the impacts on wildlife and on just flora and fauna in general.

Julie: Right.

Kim: –By the work that they’re doing. So, we’ve made some inroads in causing some concern to be taken on the part of these agencies in their planning efforts.

Julie: So what would one practical suggestion be when you’re looking at twelve-foot-high or, I don’t even know how high, fences and other obstacles?

Kim: Right. Well, the first step is to identify where the wildlife corridors are, of course. And we’ve done that to some extent. And we’re working to perfect that, so that we know exactly where these wildlife corridors exist. And once we know that, we can then point to the areas and make suggestions about different types of infrastructure that might be more wildlife-friendly. Certain types of fencing, for example, will keep vehicles out but wildlife can pass through them. Now, of course those are only in areas where walls have not been built today.

Frankly there’s about 800 miles of US-Mexico border that has been solidly barricaded with walls. And some of those walls cross important wildlife corridors. And so therefore we are a little bit in the, a little bit behind schedule in protecting those areas. But, we are attempting to point out where these wildlife corridors are located as we go forward.

Julie: And not limiting this challenge to the border lands, but looking at the challenge of, for example, roads and other parts of the country. How are you helping to facilitate wildlife crossing with bridges or other kinds of easements, when it comes to highways and that infrastructure?

Kim: Sure, that’s probably the second most important concern that we have. Because regardless of how much land is conserved on either side of a highway, the fact that the highway bisects those lands really creates the fragmentation that we’re trying to avoid. And, to address that, we’ve, we’ve worked with local partners. For example, south, east of Albuquerque, New Mexico, where U.S. 40 crosses between two major mountain ranges there.

Julie: Mm-hm.

Kim: We have developed a coalition that worked with the highway department to include wildlife friendly crossing structures as part of a regularly scheduled maintenance program. And the result of that particular project has been tremendous and impressive. It has reduced, say well as a matter of fact mountain lions are one of the species that were being killed fairly regularly on that stretch of highway.

Julie: Yes. Yeah.

Kim: And through that work we’ve essentially reduced it to almost zero.

Julie: Oh, fantastic!

Kim: And there’s a multiple number of different approaches that were taken by the highway department to help that to happen.

Julie: Like culverts? Or? I’m trying to visualize what that might look like.

Kim: Well, in that particular project there were two or three overpasses, highway overpasses over streams and other arroyos, which had become completely clogged with underbrush. And so part of the project was to remove the underbrush and create, and reopen those wildlife passages. Another thing that was attempted and actually has been quite successful was fencing the highways on both sides in certain areas, and then funneling, with the fencing, wildlife into these underpasses.

Julie: Okay.

Kim: And so that has also been successful.

Julie: And does everybody tithe something to pay for those initiatives? Or how does that part work, the financing, or I guess that might just depend on the situation.

Kim: Well, it does depend on the situation. But in the case of an already existing maintenance project that’s going to cost millions of dollars, making these adjustments for wildlife may not represent that many extra dollars. So, in some cases there may not be any fundraising that’s required. And in other cases of coarse, the highway departments need to be lobbied and brought on board if there’s a large expense.

Now another example is in Colorado at West Vail Pass on Interstate 70. And as you know, Interstate 70 bisects roadless areas in many places. And so that’s been another area of focus, and our partners in Colorado — Colorado Safe Passage Coalition — has been working with the state government and the Department of Transportation there to assist them in getting a large federal grant toward building an actual overpass — a wildlife bridge as we call them — at West Vail Pass. And that is now in the planning stages and as a matter of fact there’s been a national contest for designers to submit various designs for this wildlife bridge and that’s still in process, but we expect there will be, in the next few years, a major wildlife bridge at West Vail Pass.

Kim: Well, we think it will be because we’ve already seen success with wildlife bridges in Canada. And so we expect that if we follow that same principle — in other words, making sure the bridge is wide enough and it’s bermed on the edges so that wildlife using it can’t look over and see traffic below–

Julie: Right.

Kim: –and land, it is landscaped to match the surrounding landscape — that these bridges do work.

Julie: It must be exciting to share stories with your colleagues in some of the other Wildways areas. And do you ever share researchers or conservationists or swap, surely you swap tips on how to go about undertaking a certain task?

Kim: You bet! That’s really where part of the name network enters into our organizational because we essentially exist to promote networks across the landscape, and in this case across North America, as you state. We have, well, first of all, we have Wildlands Network staff in several places around the country, some of which is in Florida, where the Florida Panther is a real focal species.

And in fact, highway passages are being constructed in Florida to accommodate the panther there. We have worked with numerous groups there and elsewhere to share this information. And, in fact, a lot of the information that we develop we make public and our goal is to get it to our partners so that they can use it.

Julie: Well, we’re about of time but I did want to say that people can get good information by visiting your website. Please tell that address.

Kim: Okay. That would be Wildlandsnetwork.org.

Julie: Great. And I have been to your network and I’ve looked at some of the maps that show the swath of land and the various areas. And what that might look like if you are successful in making that happen. Is it possible to kind of connect the dots for us now and tell us what if we were to look at your particular image, would some of the image be filled in? Are you making headway in one part of the project zone versus another?

Kim: Well, we are, first of all, the Western Wildway. As I mentioned, that was really the original project that we launched upon. And there are multiple examples throughout that wildway of lands that have been protected and connected through the use of multiple tools, mostly relating to land management on the parts of private land owners and public land managers, like the agencies. And many of those stories are told on our website, so you might be able to check those out there. But piece by piece we’re putting this together. And as you might imagine, this is not a ten year project.

Julie: Right.

Kim: This is not a twenty year project. This could be a 100 year project, and we want to be able to hand this off to future generations. But we want to make sure that we set the foundation to get the whole thing rolling.

Julie: Yes. Well I applaud you for being a part of this very important effort Ken, Kim, excuse me, and thank you for spending time with us today. Are there any other areas we might not have touched on or any parting thoughts before we say good-bye?

Kim: Well, sure. Just one quick thing, and that is that the interaction that we talked about amongst keystone species and landscapes is very key to the actual direction that we need to go here. And trophic cascades is how we refer to that interaction. And there are some brand-new materials in fact, published recently by Island Press. In fact, the name of this book I’m looking at here is Trophic Cascades, edited by John Terborgh and James Estes. And it probably is the finest work yet available on describing these interactions and the importance they have for landscape. So I would recommend to your listeners that they might check that out.

Julie: Right. And our politicians too?!

Kim: Absolutely. [laugh]

Julie: [laugh] Most importantly!

Kim: Yeah.

Julie: Well, very good. I appreciate the plug. And very nice speaking with you today, Kim. Thank you so much.

Kim: My pleasure, Julie. Thank you.

Julie: All right. Bye-bye. Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for noncommercial use. For more information visit mountainlion.org

Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for noncommercial use.