MOUNTAIN LION RESEARCH HELPS LIONS

CROSS SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA FREEWAYS

by Amy Rodrigues, Biologist and Outreach Coordinator, Mountain Lion Foundation

At First You Get Lost

On this day of field research, December 14, 2011, I set out from San Diego and headed north at about 8 a.m. I brought some granola bars and water, took a few sips of coffee, and headed out my hotel door. I was to meet up with Dr. Winston Vickers and biologist Deanna Dawn in a coffee shop 100 miles north in the City of Orange.

Winston had listed the cross streets and then given me what I generally call old fashioned directions: “Take I-5 north, after you pass the 261 get off the freeway, go up a few miles, and meet at the coffee shop in the shopping center on the corner.”

I’m 27. I don’t read street signs. I turn when Maggie (nickname for my Magellan GPS) tells me to, and I stop when she says I’ve arrived. Thankfully, she found the cross-streets. But since I was driving from San Diego all the way up to Orange, I didn’t want to risk being late. I was super-excited and more than a little nervous because I’d never seen a wild mountain lion up close before or had the opportunity to participate in this kind of research.

I was a little early and there were three coffee shops in the parking lot so I called Winston to let him know I had arrived. He and Deanna were still out in the field and running a little late.

It was mostly a clear day, with a few scudding gray clouds. The temperature was in the mid-60’s. I still felt like I was in the city. I had no idea that the road I was on actually marked the barrier between civilization and lion habitat.

In retrospect, even as a biologist I was — and still am — unable to fully comprehend the confusion and terror that two-year-old lions must feel as they are bullied out of their mother’s home territory, lost and alone, to stand facing a noisy eight-lane freeway, cars and trucks speeding past at 60 miles an hour, and the suburbs beyond. They’ve got no address to a woodland territory that just might exist off the horizon, no directions, no map, no way of knowing that the houses and roads will ever end.

Even lost, I’m lucky.

Once they arrived, Winston grabbed his laptop case out of the back seat as I walked up to the truck. He smiled, we shook hands, and he introduced me to Deanna. I felt welcomed. Both were in baseball hats with associated wildlife organization logos, long sleeved shirts, dusty work pants, and muddy boots.

“We drink a lot of coffee,” Winston said with a smile.

The Southern California Mountain Lion Project

In this busy suburban setting in the shadow of the Santa Ana Mountains, it’s hard to believe that there are still enough wildlands nearby to support California’s keystone predator: the mountain lion. Over coffee, the researchers detailed how they are studying the deaths of mountain lions on Southern California roads.

Vickers explained the driving force behind his research in this way: “We have lost over twenty mountain lions in the Santa Anas to cars alone in the last ten years (those are just the ones we know about). Our work on this with Cal Trans and the OCTCA is going to likely cut that toll dramatically in the future. That is the real on-the-ground impact of research.”

“I was only few minutes away from loud, urban greater Los Angeles, but I felt like I was in the wilderness.Amy Rodrigues

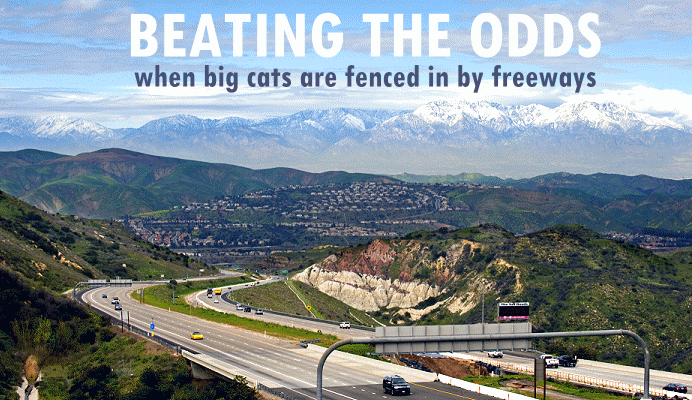

Research is especially important when it addresses such substantial ecological issues. The Santa Ana Mountain Range is virtually fenced in by the 241, 91, and 261 freeways, leaving an 800 square mile island-like patch of wildlife habitat just large enough to support about 25 adult lions. Young lions who can’t win the fight with a resident adult for real estate are forced to attempt to cross treacherous freeways in order to survive.

A recent interview with cougar biologist Howard Quigley concluded that “the main reason behind cougar decline in the U.S. is habitat loss through degradation and fragmentation. Research shows that cougars need at least 850 square miles of uninterrupted habitat in order to persist with only a low risk of extinction. With urban areas becoming more numerous, many scientists are calling for the expansion of protected habitat corridors so that cougar populations could exist and move without needing to traverse through civilization.” If this is true, then the Santa Ana Mountains are even now right on the edge of viability for mountain lions.

The Orange County Transportation Corridors Authority (OCTCA) and the California Department of Transportation have hired the research duo to figure out where lions and other animals attempt to cross, whether or not animals use the designated wildlife underpasses as intended, and ultimately what may need to be changed in order to avoid future deaths and to help connect islands of wildlife habitat with one another.

Mapping Mountain Lion Movement by Radio-Collar

While we ordered coffee, I remember thinking that the researchers looked a bit too dirty and outdoorsy to be in this cute little coffee shop in a wealthy neighborhood. Little did I know that twelve hours from now I would be back in front of this place with deer blood on my jacket and who knows what on my boots! But Winston and Deanna behaved like regulars with the friendly staff. The woman behind the counter even filled up their canteens with cold water after pouring the coffee.

I was still much too anxious to eat or drink anything. I just wanted to get out there and follow some lions! Our plan was to spend the day driving around to check baited sites (to learn whether lions came to feed on the road-killed deer the researchers left out in the wild), to check camera traps, and to see whether we could download data from any mountain lions along the way: a typical day of research.

Winston started up his computer, and explained that we were running late because they had just downloaded data from M86, one of the study’s radio-collared lions whose collar battery was running low.

Winston began talking about coordinates and pointing at the screen, which I couldn’t see from where I sat across the table. I didn’t want to overstep and wasn’t sure how privy I was to any of the information, so I held my tongue.

A moment later the researchers invited me to come around and have a look.

On the screen I saw a topographic map. I’m not familiar with the region, but I could make out a canyon with a few high ridges. Winston clicked through several drop-down menus and then — suddenly — the map was riddled with dots. Another click and the dots were connected with lines.

There were two clusters: one recorded in the daytime (M86’s daybed sleeping spot) and the other where the lion had stopped in the nighttime.

Spending the whole night in one area most likely means a big cat has recently killed prey and is feeding. Mountain lions cache the bodies of deer for several days. This behavior gives researchers the best opportunity to set a trap for recapture.

Winston pointed at the screen, saying, “This is where we downloaded the data… so he’s right about here, and we could probably set the traps around here.” Deanna agreed.

My eyes lit up, “Traps?”

“Yeah, looks like the plan has changed.”

The researchers explained how this was our best chance to recapture M86 and replace the battery. Winston looked at the clock, adding, “But we’re going to have to work fast.”

We had about five hours until sunset. Finding the location of M86 set a new objective for the afternoon.

Why So Many Roadkills? Cities Meet the Wild

The two researchers started laying out the plan. Deanna would stay back at the shopping center to buy supplies, make some calls, and check their gear for the capture. Would we try to put everything in one truck? No, I would go with Winston to get the traps from a nearby preserve where the researchers keep traps and supplies. We would all meet up at the capture site. They planned rapidly and I wasn’t sure what all of it meant at the time.

On the drive, Winston and I were chatting so much that I didn’t realize when we pulled off and were suddenly heading down a windy narrow road. The brush was thick and green on both sides. There was a hillside on the right and a culvert on the left. About ten minutes later the road opened up into a dirt parking lot in a small clearing, a grassy field with a tent, and maybe a dozen deer.

I was only few minutes away from loud, urban greater Los Angeles, but I felt like I was in the wilderness. The only buildings I could see where a handful of weathered cottages, and the only sounds were chirping birds, one loud crow, and the wind in the trees.

Traps and supplies are kept at several holding places near the study area, so that the researchers can respond rapidly to opportunities such as this one. As we pulled up to a line of empty cage traps behind one of the buildings, the antenna on Dr. Vickers truck began picking up a signal from another one of his collared cats; a young female who lives in the area. We quickly loaded two large traps into the truck bed and then Dr. Vickers grabbed his handheld telemetry device from the back seat to try and pinpoint her signal. If he could get within the line of sight, he could download her GPS data.

It was at this point I realized that “downloading” lion data isn’t just a matter of turning on the computer and clicking the download button. Using what looked like an old television antenna connected by wire to a first generation ’90s cell phone (about the size of a brick), Dr. Vickers programmed the cat’s specific frequency and began walking down a nearby path. Twisting and turning the antenna while holding it high above his head, he listened for the louder beeping that means the cat is close. Once the signal was strong enough, the device would begin downloading the data.

The process is a little like trying to receive a text message with spotty cell coverage, but with a much better arm workout. After about five minutes Dr. Vickers had downloaded the young female lion’s data. Winston thought she might be as close as 30 yards to where we had parked the truck and if she were up in a tree, she could easily have an eye on us. The deer still grazed nearby, as blissfully unaware of the big cat’s presence as we had been.

Instead of turning into the shopping center we made another turn and entered a park. At the kiosk a ranger waved us through.

Now I understood why there were so many roadkills on the freeways. This wild place was just a few steps from suburban backyards. The mountain range ran right into urban development and the lions didn’t understand the difference.

Finding the Best Place to Capture a Mountain Lion

From the data points downloaded from M86’s collar, we had a rough idea where he was currently sleeping. A few miles in, we crossed over a shallow creek. Dr. Vickers pulled the truck to the side of the road and pointed upstream. This was as close as we could get the vehicles to M86’s feeding site, which was somewhere in the brush along the overgrown riverbank. Perhaps M86 had ambushed a deer that had come down the hillside for a drink. Wrong place, wrong time, for that deer.

As we began unloading the traps from the back of the truck, two senior California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) wardens pulled up behind us. After brief introductions, I learned that they were along to help out and that they appreciate the research being done by Dr. Vickers’ team. On each trapping outing, they also bring along a couple of rookie wardens to give them a chance to see a mountain lion up close, learn more about their behavior, and prepare them for responding to potential mountain lion calls in the future. Today’s rookies were still en route, apparently stopping along the way to pick up bait for the traps: another wrong place, wrong time deer road-killed nearby that morning.

“It’s not far. Let’s take the traps now,” Winston said. He handed me a pair of work gloves and in two-man teams, the four of us began carrying the traps towards the creek.

When the brush got especially thick, Winston led us wading in the water straight up the river. Thankfully, my boots passed the water-proof test and I managed to keep up with the back half of his trap.

I was so preoccupied trying to stay in step and not lose my grip on the back of the trap, watching where I was stepping so as not to slip, that when Dr. Vickers paused and whispered, “We’re close; let’s stop here,” I didn’t realize we were already a few hundred yards off the trail and in M86’s prime territory.

I waited with the trap while Dr. Vickers hiked up a bit farther to look for M86’s deer cache. Alone for a moment, I caught my breath. It was quiet, wild and peaceful. Again, all I could hear were birds and the wind.

The two CDFG guys were a good fifteen yards behind and had stopped to adjust their grips on their trap. I motioned to them that this was the spot and we all waited patiently for Dr. Vickers to return.

A short time later he emerged from the bushes. He whispered that he couldn’t find M86’s deer, but that he had found remains of bait he had left out before and had identified a couple of good places to set out our traps. He reminded us to keep our voices low and to say as little as possible. Sounds echo in the canyon, and the last thing we wanted to do was scare M86 away.

Back at the waiting site up the road (where we spent most of the night) the only indication that we were anywhere near civilization was the 241 bridge looming over us, the sound of cars whizzing by, and an occasional truck horn.

Since the study began with the first collaring of a cougar in 2001, 30 GPS-collared cougars have died while circulating in the wild, all but 1 while still wearing GPS collars. One additional individual was shot illegally but recovered.

This figure represents 53.6% of the 56 radio-collared cougars monitored to the point of their death in the wild or being lost to monitoring due to collar drop off or malfunction, or other factors. The majority of deaths (63.3%) involved some sort of interactions with humans (car strikes, depredation permits, illegal shootings, legal shootings, and human-origin wildfires).

Causes of death for radio-collared cougars circulating in the wild were:

Car strikes:

6 of 30 (20%)Depredation permits:

6 of 30 (20%)Disease confirmed or strong circumstantial evidence:

5 of 30 (16.7%)Unknown:

4 of 30 (13.3%)Illegal shootings:

4 of 30 (13.3%)Fire:

2 of 30 (6.7%)Unknown but evidence of trauma of unknown cause:

1 of 30 (3.3%)Shootings deemed legal due to perceived threat:

1 of 30 (3.3%)Intraspecific strife:

1 of 30 (3.3%)The status of collared cougars whose collars dropped off or stopped transmitting prior to recapture, and captured kittens that were never recaptured for GPS-collaring, is unknown. Some of those previously captured and / or collared cougars whose status is unknown are also likely deceased given the mortality rates for collared cougars in the study.”

Baiting Cage Traps for Capture

Dr. Vickers and Ms. Dawn use large cages with bait to trap their research lions. Some researchers use dogs to track and tree the cats, while others prefer snares.

Cage traps are believed by many to put the least amount of stress on the animals. They aren’t chased to the point of exhaustion as is often the case with dogs, nor do they suffer any circulation or nerve damage which are common side effects from being snared for even just a few hours.

To reduce the stress on their lions even more, the cages Dr. Vickers uses are fitted with VHF radio devices. He stays the night parked in his truck within a few miles of the cage, and as soon as the cage is triggered, he receives a signal and heads out to quickly sedate the cat.

If he went home for the night and returned in the morning (which would be far more convenient for a tired researcher), by then the cat would be stressed and likely have broken a few teeth and claws on the cage bars trying to escape. By taking this particularly humane approach, Dr. Vickers reduces the negative effects of capture and collaring on the lives of these lions.

We determined where to place the traps, near the water, about twenty yards apart, on patches of flat ground along what appeared to be game trails. Though lions prefer to stay hidden and hunt from the bushes, they — along with deer and other wildlife — often use cleared trails to traverse the landscape. We lined the bottoms of the traps with leaves and placed large rocks and logs behind the backs.

Deanna and the two rookie CDFG wardens arrived with the fresh road-killed deer. I’ll leave out some of the specifics here for people who may be a bit squeamish. But ultimately we had a brief deer anatomy lesson and separated some of the organs (tasty parts for a lion) and limbs to use as bait in the two traps.

Dr. Vickers took some bait and headed to the other trap while I stayed with Deanna to help bait the closer one. She crawled into the trap and with strands of sturdy wire, began tying the bait to the back of the trap. Afterward, we added more logs outside the back of the trap to prevent the lion from trying to get to the food through the bars.

Apparently, on a previous trapping outing, Winston and Deanna showed up ready to collar a lion only to find that the entire trap was missing. Thinking that someone had stolen their trap, or worse, poached the lion and took the evidence, the researchers immediately notified CDFG and began reviewing images from the motion capture camera they had placed at the site.

The researchers quickly figured out just what had happened. The lion approached the trap, bypassed the obvious trap door and tried to pull the meat through the bars on the back of the trap instead.

Hungry and frustrated, the lion ended up dragging the large trap halfway across the canyon until finally getting it caught up in some bushes. This time, we were sure to place plenty of barrier objects behind the trap to avoid a repeat of that scenario.

The traps were fully baited and the cameras mounted. The traps were set and on each door was fixed a small radio device with a pin on a string.

If a lion were to enter the trap and step on the floor plate, the door would drop, tugging on the string and causing the pin to be pulled from the radio device. When the pin is removed, the device begins emitting a radio signal which we could pick up from the truck.

When we heard the “door down” signal, we would return to the site immediately: to sedate M86, change his battery, and let him go free as quickly as possible.

It was now getting dark and with the traps ready for action, we loaded the remaining deer meat into garbage bags (ensuring the only free food would be in our cages) and I helped drag a larger piece of the carcass back to the trucks with one of the rookie wardens. The smell definitely was not appetizing to me, but hopefully the lion would feel differently.

Waiting for a Mountain Lion to Trip the Trap

Back at the trucks, our group cleaned up with baby wipes as best we could and drove a few miles farther up the road to give M86 extra space and quiet. It was time to play the waiting game.

During the first hour, we found some mountain lion tracks in the sand and the CDFG wardens used this opportunity to teach the new guys how to identify mountain lion tracks. We talked about the three-lobed heel versus a dog’s two lobes, the absence of claw marks on feline tracks, overlapping stride, and toe spacing.

An hour later we shared some cookies and granola bars. As time passed it became colder and colder. We all bundled up in our jackets and stood around talking. Dr. Vickers and Deanna shared stories about previous captures, explained how most of their lions end up as road-kill, and debated about what our chances were for catching M86 that night.

Around 9 o’ clock, Dr. Vickers opened his laptop and began showing us some of the maps of his collared cats in the region. We could see where their home ranges overlapped, where they tried to cross freeways, and in one case where a cat walked along the shoulder of the road obviously looking for a place to cross before eventually giving up and turning back. If only he knew that had he walked for literally one more minute, he would have come to a wildlife crossing underpass.

Unfortunately the easiest places for people to build crossings aren’t always in the same locations where lions want to cross. Dr. Vickers pointed out that putting some fencing along this stretch of road might help funnel wildlife to the safer crossing areas.

Still no trap door down.

Another hour passed and it started to rain. Everyone dispersed to their vehicles to get dry and warm. Only Deanna and Dr. Vickers stayed outside; checking their gear and prepping their backpacks in the event we catch M86.

By 11:00 I was cold, wet, and unsure whether I was starving from not having a real meal all day or nauseated from smelling like dead deer. I had finally succumbed to simply watching the clock, since I still had to drive back to my hotel in San Diego and catch a flight back to Sacramento the next morning.

The temperature continued to drop and Dr. Vickers was finally ready to join us in the trucks to get warm. He sat down and warmed his hands over the heater vent. Then he glanced over at me and said, “You know, I’m going to check the signal one more time before I get comfortable. I have a good feeling.”

He stood outside twisting and turning the antenna, holding the speaker close to his ear to listen for the “door down” signal. His eyes lit up and he called Deanna over to confirm what he was hearing. She held the speaker to her ear, smiled, and in an instant our mood changed. Excitement overtook cold exhaustion and we all jumped from our cars, ready to see what was in the cage.

Meet Santa Ana Mountain Lion M86

As we all caravanned back to the closer parking lot, Dr. Vickers handed me a clipboard and asked if I would be comfortable staying by his side during the whole process and recording his notes while he worked on the cat.

I was thrilled! I was hoping to get to stand close enough to observe the sedation and take some photos, but to be up close and entrusted to take notes was truly an honor!

“Yes, of course,” I replied as calmly as I possibly could.

Everyone arrived at the trailhead and Dr. Vickers and Deanna began handing out gear from the back of the truck for everyone to help carry up the river. There were full backpacks, two large tackle boxes with many compartments full of medical supplies, a folded-up tarp to lay under the sedated cat, a pole to inject the cat from a safe distance, a cooler to hold blood samples, an emergency kit, and a few other supply cases.

After a quick double check that we had everything and a reminder to keep our voices low to reduce stress on the cat, we began the single-file hike back up the river. With flashlights and headlamps, we slowly and quietly made our way to the first trap.

Before I realized we had arrived, I heard the low rumble of a growl followed by a few angry hisses. I looked up and in the light of a warden’s headlamp, saw a very angry M86 in the trap that I had helped Deanna to bait. The radio collar around the lion’s neck looked like a formal bowtie, but he was clawing at the bars and hissing as he tried to look tough and scare us away. He was not a happy cat.

Once M86 was sedated, we would check his vitals (temperature, breathing, pulse, and oxygen) every five to ten minutes to be sure he was doing okay. It was my job to watch the clock and record the data on Dr. Vickers’ capture sheet.

M86 was one of the feistier cats Dr. Vickers had captured. He was agitated, growling, hissing and swiping a paw when anyone approached the cage. The senior wardens told the rookies to take note of this behavior, adding, “He’s afraid, and this is his way of looking intimidating to get us to leave him alone. It looks threatening, but really this guy just wants his space.”

“You might get a call from a homeowner saying there’s a mountain lion in a tree and it’s hissing. This is normal lion behavior and you need to react calmly to the situation. The media shows up and all the cameras are going to be on you so keep a level head,” the other warden added.

I quickly chimed in, “Yeah, and if you shoot a cat for no good reason you’re going to have those Mountain Lion Foundation folks on your back real quick.”

The senior warden smiled, “Yep! Most folks don’t want to see a lion killed. That’s why we brought you here today to get exposure, to see a lion up close, and to hopefully remain calm if you respond to a lion call in the future.”

A month or so prior when M86 was captured for the first time, Dr. Vickers noted that he was pretty scratched up. He appeared to have been in a fight with another cat. Just days before my visit, the research team had captured a larger male lion (M87) in the same area. This was likely M86’s competition.

M87 hadn’t much minded being caged and simply lay there as the researchers approached and sedated him. Unfortunately, M86 was not so cooperative.

The first attempt to sedate M86 failed. He broke the needle and only received a partial dose, but after a few more attempts we were able to properly sedate him and get to work.

Dr. Vickers noted M86’s facial scratches were healing nicely, but he put a little antiseptic cream on them to help the recovery process. M86 was obviously a tough cat and after fighting another lion to keep his home range, it was no wonder he was so upset to be in our cage. To stay alive, he always has to be on guard.

Although M86 was now unable to move, he was still somewhat aware and not completely unconscious, as putting an animal completely “under” is dangerous.

Dr. Vickers decided that trying to carry the cat to the work area would be difficult and add more stress, so we quickly moved the gear to the cage where M86 was finally beginning to get comfortable. To reduce additional stress, Dr. Vickers placed a loose hood over the cat’s head, which helped to block out some of the light and movement. He seemed to relax and his pulse returned to normal levels.

I watched my clock and stayed vigilant with the record-keeping. The lion’s vitals looked good as Dr. Vickers unscrewed the battery compartment on the radio collar and placed a new battery. A few blood samples were drawn and with the help of some straps and a scale attached to a long bar, we were able to get his weight. He was a little light at around 130 lbs but seemed otherwise healthy with few parasites.

When we were finished, but before M86 came out of sedation, I was excited to be able to touch the lion for the first time. His fur was nowhere near like a housecat: courser, shorter, rough and dirty.

The whole process was well organized, efficient and only took about a half hour.

When all the samples were gathered and photos taken, the CDFG wardens helped carry M86 across the stream to a flat grassy area. It was safer for the cat to recover there rather than risk stumbling down the slope and into the water.

As the rest of the crew helped to pack up the gear, I stood with Dr. Vickers over M86 as he began to come out of sedation. Although he was still mostly incapacitated — only able to lift his head and shake a paw — it felt amazing to be this close to a wild mountain lion without cage bars between us.

M86 is a beautiful — really majestic — animal. I’ll never understand how anyone can shoot a lion for fun.

Just as I started to get a little nervous, M86 stumbled and fell face-first back into the grass. He slowly began to get up again and took a few more steps. We watched as the drugs wore off and M86 regained his balance.

“OK. I think we should head out now,” Dr. Vickers whispered.

We backed away slowly and made our way to the group hiking back up to the truck. They had taken all the extra deer meat out of the traps and left it close by to ensure that M86 got a good meal that night.

At the End of A Long Day

Back at the cars we were all still pumped from the excitement but got the gear loaded, said our goodbyes and headed on our separate ways. Dr. Vickers dropped me off at my car back at the coffee shop and I thanked him again for the amazing experience.

What a thrilling yet exhausting night! I didn’t get back to my hotel room until 4 a.m. with just enough time to shower, pack, and get to the airport to catch my flight.

I don’t know how mountain lion researchers have the energy to do this night after night, but I sure appreciate that they do! Their data helps us better understand this mysterious cat and puts us one step closer to ensuring the species’ survival for generations to come.

Last I heard, M86 was still alive and well, and still defending that same territory from M87, the bigger male. Dr. Vickers emailed me recently: “We’ll keep our fingers crossed on 86, but all of the cats we’ve collared in that area occasionally cross the freeways at unsafe points.” With more than 75% of lions in this range dying at human hands — road-kill, poachers and depredation — I’m glad he’s beating the odds.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email