The Man Who Made California Safe for Lions

Guest Commentary by Liza Gross of QUEST, a science and environmental series of KQED San Francisco.

Forty-two years ago, California’s mountain lions got a break from an unlikely ally. Lowell Dunn, the president of Vallejo’s Rod and Gun Club, wrote Assemblyman John Dunlap that he thought the time had come to stop shooting mountain lions. The hunter’s plea sparked the beginning of the end of state-sanctioned persecution.

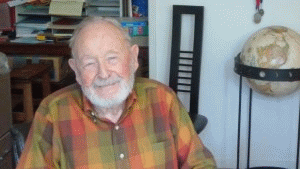

“He hoped that somehow there’d be a way to continue the existence of the lion,” recalls Dunlap. The 89-year-old Napa resident left the political stage more than three decades ago, but admits to enjoying a good political fight in his day, especially for a good cause. The hunter couldn’t have chosen a better legislative target.

Dunlap, who started an eight-year run in the Assembly in 1966 and then served four years in the Senate, had always believed in preserving wildlife, he says. He readily embraced the lion’s cause. “I recognized that we were invading their habitat, that there was a conflict, and that we needed a more thoughtful approach.”

A self-described “strong Democrat” and Sierra Club member, Dunlap won the big cat its first reprieve from hunters’ crosshairs with a moratorium on sport hunting, signed by then Gov. Ronald Reagan in 1971. The moratorium went into effect when the scheduled lion hunting season ended in February 1972.

Dunlap met stiff opposition from livestock ranchers when he first introduced his bill, in 1970. But the next year he encountered less resistance, which he credits to a burgeoning ecological awareness and support from his district. He recalls that Starr Baldwin, famed editor of the St. Helena Star, told grape-growers at a local meeting they should welcome lions because they feed on deer and raccoons, no friends to grapevines.

Initially, Dunlap sought the support of the state Fish and Game Commission but quickly realized he’d better look elsewhere: “They were pretty much hunter dominated.”

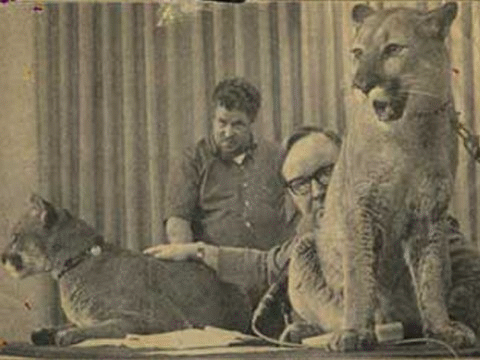

Dunlap turned to wildlife preservation and conservation groups instead, but credits the lions themselves with ensuring the bill’s passage. His legislative assistant, Mike Gage, met two tame mountain lions at a meeting to build public support for the measure. “He got the idea that if we introduced the bill and had a press conference with the lions, that would be a great sendoff.”

“I thought it was grandstanding, but recognized that it did have value,” he adds. “And I had enough ego that I liked to show off, so we did it.”

Dunlap took questions at his Capitol press conference flanked by two rather imposing lions. He admits the cats made him nervous, though they were leashed, with their handler a few feet away.

Nine months later, California enacted the first measure in the country to protect lions. It remains the only state to outlaw trophy hunting of lions, after residents voted twice to uphold the ban.

Dunlap has no illusions that trophy hunters will ever accept the notion that lions should be protected. Even so, he has little patience for Fish and Game Commission President Dan Richards, who recently won notoriety by traveling to another state to kill a mountain lion.

Richards bagged his trophy in Idaho, where such kills are legal and so, his defenders insist, no big deal. Had he killed a lion in California, he could have been fined up to $10,000 and sentenced to a year in jail.

Dunlap is not among his defenders. “I certainly sympathize with trying to do something to point with shame,” he says. “I can’t say he doesn’t have a right to do it, but I don’t think it’s very good judgment.”

(Richards was voted out of the presidency by his fellow commissioners at their August 8, 2012 meeting.)

Dunlap says he never had the inclination to hunt, adding with a sly smile, “I was born without any wisdom teeth, which maybe shows I haven’t developed the hunter quality.”

“I suppose killing animals is the way we used to survive to protect ourselves and get food,” he muses. “Now it’s a sport, and I would hope as time goes on we would find other things to do.”

Dunlap says he wanted to protect the mountain lion not just to preserve a single species but to send a wake-up call to governments to protect the environment before it’s too late. “My idea was, when in doubt, preserve.”

Ecosystems are complicated, he says. “If we screwed up the wrong ones at the wrong time it could end up threatening our own way of life and happiness, let alone existence.”

When Dunlap pitched his mountain lion bill on the Assembly floor in 1970, he pointed out that in the early 1900s just two passenger pigeons remained in the world. “They were both male,” he says. “We woke up too late on that.”

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email