Guest Commentary by Nina Kidd, writer, nature photographer and advocate for wildlife conservation.

Cougar! The news went out by cell phone and Twitter: A baby mountain lion, 75 lbs., Female. No — Adult. Male, about 95 lbs.

News bites on cell phones alerted residents. The confused stories featured a blurry shot of a mountain lion curled on the tile floor and peering up through the fronds of a tropical potted plant.

The photo confirmed that reporters got the main thing right: A mountain lion (also known as a cougar) had appeared in their town.

Helicopters clattered above the three-story building. Bystanders snapped photos of police stringing yellow crime-scene tape.

Local newspapers reported a chaotic scene in the 40′ x 40′ patio of the building, where officers blasted fire hoses and pepper spray “to contain the beast.”

Keeping an eye on the mountain lion, the police weighed their options. They had phoned for Fish and Game wardens and National Park Service biologists. Fish and Game darted the animal with a tranquilizer. Vets and biologists inject drugs that briefly put animals to sleep so they can examine or transport them without injury. To the mountain lion, already agitated by the noise, glass walls and jittery humans, the stinging tranquilizer dart was the final straw. He broke toward daylight. A policeman shot the animal dead.

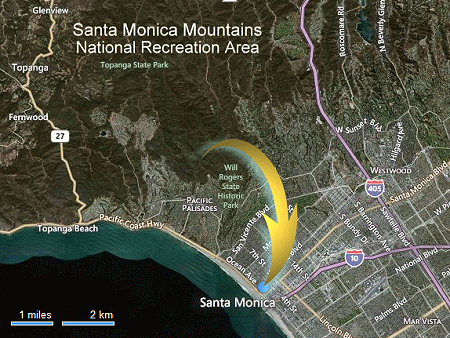

Later reports from participants varied, but the result was clear. When National Park biologist Jeff Sikich arrived, he sent the news to headquarters. One more mountain lion, a young male and apparently healthy, was lost to the precious wilderness in Southern California. A post mortem exam revealed that the male was two to three years old, and his DNA showed he was probably offspring of the small population of mountain lions living in nearby Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, directly northwest of Santa Monica.

But from all sides, questions poured in. What was this animal doing in town? And why did he leave the mountains that were his home?

The short answer is, the young cat was lost. He wasn’t looking for food. Based on the condition and habits of lions they have followed, Park Service biologists believe that the supply of mule deer in the Santa Monica Mountains is sufficient to feed the mountain lion population there, estimated at ten to fifteen, including females.

The natural tendency for each young male to move out and establish his own home range — called dispersal — is what keeps the genetic line strong. Typically, mountain lions live far apart across varied landscapes. Once established, each young adult male would be defending his own new home range, each covering 200 square miles or more. (Adult females’ ranges, which can measure 75 square miles, are often located within a male’s range.)

But in the Santa Monica Mountains, all suitable mountain lion land is bounded by city and suburb, and sealed quite tight by the Santa Monica Bay to the south, busy eight-lane freeways to the east and north, and croplands to the west.

In 2002, biologist Jeff Sikich and his colleagues found that the home range of P1, the first adult male mountain lion they followed, encompassed nearly all of the Santa Monica Mountains’ 153,025 protected acres. P1 mated and fathered a litter of four kittens, two of them male. Two years later, only a single female kitten survived. The rest of the litter had been killed by other mountain lions.

In 2012, the National Park Service data told scientists that the mountain lion population in the Santa Monica Mountains is hanging on. But recently biologist Sikich called the animals’ situation ‘dire.’ The young male shot last May in the Santa Monica office building left a population where DNA has indicated at least two instances of first-order mountain lion inbreeding (specifically father-daughter matings).

Human incursions, especially the splitting of wilderness lands by highways and development, are threatening the present and future of large and even medium-sized mammals all over the western U.S. Their habitat is becoming fragmented. And mountain lions, who need so much room to roam, will be among the first to go.

So, what can be done to save them?

The Good News

Since at least the 1940’s, wildlife biologists around the world have been thinking about the threat of habitat fragmentation. Recently, mountain lions in Southern California have been helping find solutions. Their needs, as well as their abilities, could make the mountain lion the 21st century poster child for a lifesaving idea that conservationists everywhere are embracing: wildlife corridors.

Wildlife corridors, also called wildlife linkages, can take many forms. Ideally, a wildlife corridor is a swath of natural land protected from sights and sounds of humans so that animals feel safe moving back and forth along them to find new habitat, and mate with others of their species there to ensure their kind will survive.

Until the late 1980’s, however, the wildlife corridor idea remained mostly a theory.

The Cougar Connection

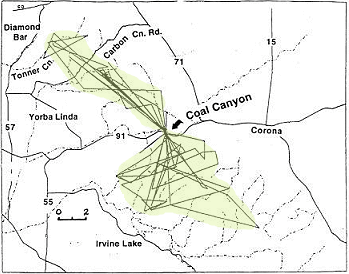

In 1988, Dr. Paul Beier, a wildlife ecologist in California, embarked on the first study of near-urban mountain lions in the nation. Dr. Beier found and monitored pathways the mountain lions used to navigate roadways and parkland in 800 square miles of the Santa Ana Mountains (south of Disneyland).

Over the course of five years (1988-1993) Beier and colleagues radio-collared and monitored 32 mountain lions, including adults and kittens. (Read Beier’s study,The Cougar in the Santa Ana Mountain Range, California).

Mountain Lions on the Map

Beier’s study revealed that mountain lions will find and discreetly use very narrow strips of land (such as drainage culverts under roads and even dangerous freeway undercrossings) to reach mates in nearby habitat patches.

However, Beier also found that the three major pathways or corridors mountain lions used in the Santa Ana Mountains were all at risk of being blocked by planned suburban development projects.

Using mathematical models, Beier predicted that unless those and other corridors were kept open (and planned housing developments and roadways were relocated), the mountain lions that had been living in those Southern California mountains for thousands of years would begin to die off, mountain by mountain. The species could disappear from Southern California forever.

More Bad News

If they go, mountain lions, the last widespread top predator in North America, might not die out alone. Aldo Leopold (1887-1948), known as the father of wildlife ecology in America, likened a self-sustaining wilderness to a complex mechanism, like a watch. He wrote to would-be wildlife managers, “. . .who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.”

Corridor Planners Need Mountain Lions

Wildlife corridors are custom projects. The design of each one depends on the local topography, the types of barriers, the surrounding land use, which animals and plants are most in need of connectivity in their landscape, and many other factors. A crucial element to building them is the will to action.

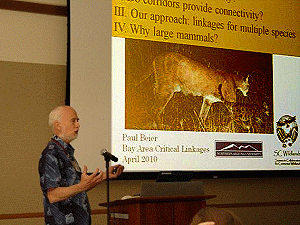

Twelve years ago, a group of young conservation biologists in California noted with impatience the accumulation of solid habitat fragmentation studies that sat useless on library shelves. Few people had acted on them to build actual corridors. For the first time, these biologists invited scientists as well as land use planners and stake holders from all over California to a meeting at Southern California’s San Diego Zoo.

In 2001 the group published a map, with an explanatory report, that pointed out over 300 “Missing Linkages” throughout the State of California, some usable by wildlife, most needing restoration, and all requiring long-term legal protection.

Read the latest Missing Linkages reports on the SC Wildlands website.

Dr. Paul Beier, by then an acknowledged expert in corridor design and implementation, urged committees representing each of the state’s eight eco-regions to identify as many as fifteen or twenty key, or focal, species that planned linkages should accommodate. Because of the mountain lion’s need for so much wild habitat, and its ability to find and use wildlife corridors, the committees identified the mountain lion as a focal species for seven out of the eight eco-regions in California.

Dr. Beier took the statewide planning idea to Arizona. Now, besides California, Florida, Arizona and Montana, Oregon and Washington have developed or are in the process of developing statewide connectivity maps. Local participation in planning is leading to actual progress on the ground.

Meanwhile, Back in the Santa Monica Mountains

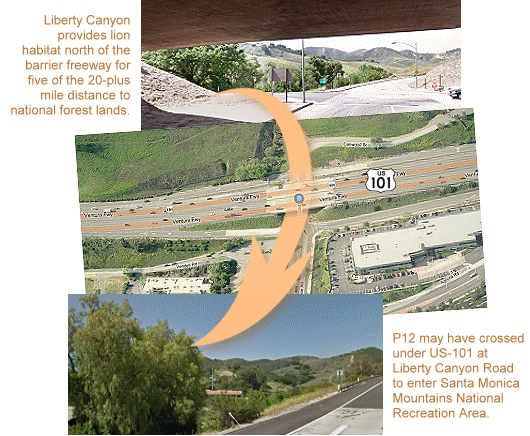

Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, birthplace of the young mountain lion in this story, was certified in 1978, a national park partnership that includes three existing state parks and spaces around them. Though initially there was no stated plan to acquire land needed for wildlife corridors, and supporters of the park disagreed about land purchase priorities, the next year, The Santa Monica Mountains Comprehensive Plan (1979) called for wildlife corridors for “maintaining open spaces between areas of urban development for purposes of wildlife movement.” Those purchases were slow in coming. Ten years later, studies by the National Park Service, biologist Michael Soulé, The Nature Conservancy and the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy advised urgently that, even though the Los Angeles to Ventura Freeway (Interstate 101) traversed potential corridor and linkage areas, “land to the northeast and south of Cheeseboro Canyon could still act as habitat and corridor zones.” Essentially, the latter area, Liberty Canyon, was the only place possible for a link between the core of the park to the south and the open space in the Simi Hills and Santa Susana Mountains to the north.

On both sides approaching the 101 Freeway, Liberty Canyon has been carefully restored with native plant cover. Several mountain lions that park service biologists radio-collared have ventured down its ridges, close enough to see the natural hillsides beyond the eight freeway lanes in their way. Since 2002 however, when the current Santa Monica Mountains study began, the scientists know of none that ventured onto the freeway surface and survived. They have confirmed that half a dozen mountain lions suffered fatal collisions with vehicles on roadways in the area, including two of the cats that were killed on a commuter road that cuts through near the center of the Santa Monica Mountains range. This number is out of the 26 animals counted in their study during its first ten years, plus the six (seven including the mountain lion killed in Santa Monica) seen, but never collared for study.

A Solid Case for Connectivity

The value of a wildlife corridor for the animals in the Santa Monica Mountains was demonstrated most dramatically between 2009 and 2012.

On a February night in 2009, GPS data confirmed that a radio-collared male, known as P12, who had been ranging north of the 101 Freeway in the Liberty Canyon area, had made a significant move. His collar was transmitting inside the park, but now it was south of the 101 Freeway!

This was an exciting first. How had he managed it? No one could say for sure, but based on the sequence of location points, it seemed likely that he used the freeway undercrossing at Liberty Canyon, a street that would be less busy at night.

The good news for this small inbred population is that P12 brought the gift of new genetic material from the north to the very closely related in-park mountain lions. P12’s offspring, currently ranging in the park, now carry some of his genes, which could help maintain increased genetic diversity in the population there for some years to come. If only passage there could take place regularly, and northward as well as southbound!

The California Transportation Department, Caltrans, has drawn plans and, along with private conservation groups, has been looking for funds to build a dedicated wildlife corridor under the 101 Freeway. The cost is estimated at $9.42 million. The Liberty Canyon Wildlife Corridor would be a major step to realization of that lifesaving north-south link.

Dr. Seth Riley, Wildlife Ecologist for Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, has been studying carnivores there for over twelve years. He co-edited and contributed to Urban Carnivores, published by The Johns Hopkins University Press in 2010. Besides the mountain lions (study begun 2002) he continues to study coyotes and bobcats (the bobcat study in cooperation with UCLA doctoral candidate Laurel Klein Serieys since 2006). Evidence from both coyotes and bobcats confirms that they too have been affected by the habitat fragmentation caused by freeways, as well as by other human-caused hazards. These other species should also benefit from the planned wildlife corridor.

The Liberty Canyon Corridor: Just a Start

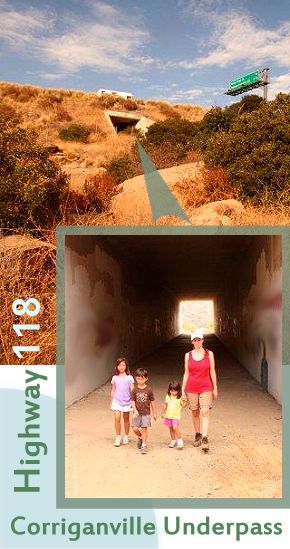

After crossing the 101 Freeway, animals from the Santa Monica Mountains must still traverse a second freeway, State Highway 118, as well as a broad major roadway, State Highway 126, if they are to complete the 26-30 mile trip to Los Padres National Forest.

The National Park Service biologists, following radio-collared mountain lions, have expanded their wildlife connectivity studies and efforts northward to include those roadways, and routes through the Simi Hills and the Santa Susana Mountains. The scientists are assisted by university students, volunteers of all ages and the biologists at Caltrans.

If the story of this one park, this one linkage, sounds difficult and expensive, it’s true. Re-connecting the wild is an enormous job. But there is growing agreement in scientific and conservation communities that wildlife corridors are our best hope for saving mountain lions and maintaining the ecological balance in our wild lands.

With a functioning linkage north out of the Santa Monica Mountains, perhaps the next young male mountain lion, instead of blundering into Santa Monica to his death, might safely find his way north to a new wild home.

Dr. Paul Beier, an advocate for mountain lions and wildlife corridors, is convinced that the connectivity movement will grow, and that corridors will do much to keep our precious wilderness areas alive.

Talking of it, he smiles and spreads his hands. Supporters will continue to join in corridor work with enthusiasm because, he says, it’s a wonderful experience: “It connects people to the land.”

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email