Failing the American Lion

By MLF Staff, written for Animal Welfare Institute’s Quarterly Magazine

Introduction

Mountain lions were once acknowledged as great hunters and revered as symbols of bravery and strength. But as Europeans settled across the continent, the indigenous peoples’ respect was replaced with fear. Mountain lions were perceived by Europeans as dangerous competitors vying for the abundant game of the New World and threatening domestic livestock: rivals cheaper to eradicate than to safeguard against.

Four hundred years later, many Americans still fear mountain lions despite the miniscule number of recorded attacks and even fewer fatalities. Deer, elk and antelope are no longer truly required as a supplemental food source for people, but hunters still consider lions to be unwanted competition and blame the cats for diminishing game herds. Facing massive deficits, federal, state and local governments still find it politically expedient to spend tax dollars to kill mountain lions rather than insist that commercial and hobby ranchers assume responsibility for their actions and provide adequate livestock protection measures.

It is against this wall of irrational fear and long-held prejudice that the mountain lion protection movement must contend. As an apex predator, mountain lions are considered by many biologists to be a critical component of a balanced and healthy ecosystem. But despite the nods given by state game agencies toward the value of the species in this role, most agency actions reflect traditional biases rather than scientific knowledge.

“Protecting” Mountain Lions in America

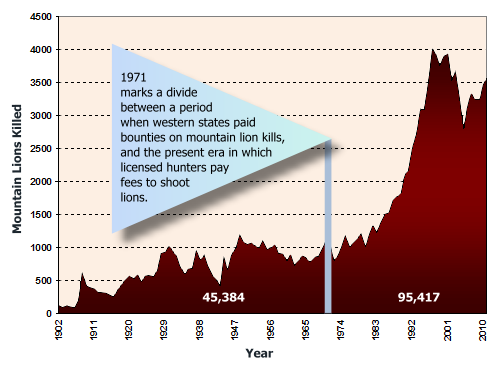

As early as 1684, bounties were being paid to kill lions. The practice became so pervasive that Puma concolor was eradicated east of the Rockies by the end of the 19th Century, and reduced to just a few thousand survivors in 11 western states when bounty programs were discontinued in the 1970s. While there is no way to ascertain exactly how many lions died in America under the bounty, we do know that over a 69-year period (1902-1971) at least 45,384 lions were turned in for the bounty in those western states which today still have viable mountain lion populations.

Mid-century, the states decided that lions required protection from unregulated hunters. This may have been in response to diminishing numbers of lions, or perhaps because the demand to kill lions was high enough that dollars could be saved by charging fees rather than paying bounties. The species was placed under the authority of the various state game agencies. It was a case of placing the fox in charge of the henhouse. The protection lions received was from commercial hunters. In season (which in some states is year round) any hunter willing to pay the few bucks needed for a hunting tag could now legally kill any lion. And while the barbaric practice of paying a bounty for dead lions ceased, discrete “Wildlife Services” programs were created to lethally “remove” lions that preyed on domestic livestock or threatened game herds. Once again, tax dollars paid for these kills.

The sad fact is that over the past 40 years of game agency control at least 95,417 lions have been reported killed. Twice as many lions killed in less than two-thirds the time? Maybe Puma concolor needs a new protector.

Managing Mountain Lions for Hunting

All state game agencies (with the exception of California, which claims that it does not manage mountain lion populations) “manage” lions not for the benefit of the species, but to fulfill the desires of hunting constituencies. All (including California, when it determines to take management action with respect to a particular lion) use guns as their primary management tool.

At the turn of this century “enlightened” game agencies started to produce elaborate mountain lion management plans. The documents seem to be created to spin the hunt by linking the plans to science. But as noted by Drs. Ken Logan and Linda Sweanor in their seminal 2001 book Desert Puma: “hunting management is a far cry from science.”

The plans—hundreds of pages long—characterize the biology and behavior of lions and the management history of mountain lions in that state. The official documents use catchy phrases like “manage for sustainable population” and tout impressive sounding strategies such as “practicing adaptive management,” and “manipulating source-sink dynamics.” States justify decisions with excerpts from the scientific studies they like, and omit those they don’t. But all the plans boil down to presenting the conditions and parameters under which X number of lions can be killed for sport.

Most states, such as Arizona, are even fairly blatant about their primary objectives:

The Department’s goals are to manage predators in a sustainable manner integrating conservation, use, and protection, and to develop the biological and social data necessary to manage predators in a biologically sound and publicly acceptable manner. Overall, mountain lion hunting is meeting the Department’s management objective of maintaining an annual harvest of >250 animals/year and providing recreational opportunities for >6,000 hunters per year. Harvest and tag sales have met or exceeded these levels during recent years.

Arizona Game and Fish Department

Can state game agencies really achieve sustainable lion populations with ever-increasing mortalities?

Dr. Brian Miller, a cat specialist at the Denver Zoo, has explained that “predators did not evolve with the threat of predation, and thus have slower reproduction rates.” He goes on to say that “When maximum rate of reproductive increase is slow, it makes more sense economically to overexploit in the present than to kill limited numbers in a sustainable fashion over the long term. Thus, knowledge of economics leads to unsustainable hunts, which shatters the myth of managing wildlife intelligently over the long-term.”

Lion population estimates are highly subjective, variable, and widely viewed as inaccurate. Quota setting rarely reflects the actual status of lion populations. For example, Drs. John Laundre and Tim Clark once reported that hunting quotas in one part of their study area in Idaho were set at their highest levels at a time when research showed that the mountain lion population was at a low point. They concluded that “none of these management approaches offers much security for the long term survival of puma populations, yet they are variously institutionalized in state management programs.”

Effects of Sport Hunting on Mountain Lions

Since the 1990s, most western states have liberalized lion hunting practices by increasing total as well as female mortality quotas, extending hunting seasons, and reducing lion tags to bargain-basement prices.

The majority of the time, adult female lions have dependent kittens. Offspring remain with their mother for nearly two years, learning all they need to know to become successful lions and avoid people.

If a female lion is killed, there is a high probability that cubs have been orphaned. Kittens less than a year old will likely starve to death. While older juveniles may be able to fend for themselves, there is an increased chance of coming into conflict with people. Thus, shooting a female lion for sport may result in the death of the whole family.

The risk of over-hunting has been heightened as more hunters seek “trophies” and are able to access remote areas on the growing matrix of roads available to all-terrain vehicles and snowmobiles.

Besides the obvious fact that we might one day lose the North American lion to excessive hunting, the “sport” also creates an unnatural selective pressure that affects the genetics of mountain lion populations. Multiple studies have demonstrated that excessive or nonselective mortalities can disrupt the dynamics of local lion populations. Changes in age and sex ratios, and the reduction or extirpation of mountain lions in one subpopulation can destabilize a metapopulation.

False Assumptions

Often the assumptions that drive mountain lion management decisions are scientifically unsupported. Improving livestock protection and human safety are frequently cited as benefits of hunting. We know, however, that it is impossible for hunters to identify and target those mountain lions who are most likely to come into such situations. Due to hunting, lion populations are getting younger, and younger lions are more prone to conflicts. Hunting is likely increasing the risks rather than reducing them.

Concerns that mountain lions inhibit the growth of game herds in the West are also unwarranted. The health of ungulate herds has much more to do with blocked migratory routes and habitat degradation, fragmentation or loss. Many agency officials have stated publicly that eliminating lions would do nothing to help increase the size of deer herds. But such arguments are usually rejected by those who make the final decisions. According to Dr. Howard Quigley, one of our nation’s premier lion researchers, “When elk herds go down our immediate response is to go out and round up the usual suspects, [and] those tend to be the predators.”

The Real Decision Makers

Game commissioners’ final decisions about how many lions will die and where the killing will take place are based less on scientific analysis than on what deer hunters and the rural populace demand. According to Dr. Quigley, “Across the West, commissions are wrestling with this and really turning back some of the advances we’ve made in managing the cougars.”

South Dakota is a blatant example of exactly how little science influences decision-makers. South Dakota extirpated their indigenous lion population in 1906. By 1997 it was estimated that there might be as many as 50 lions residing in the Black Hills region of the state, representing an extremely slow process of re-colonization. Eight years later, South Dakota Game, Fish & Parks (SDGFP) removed the lion from the state’s threatened species list and reclassified it as a big game animal. Just two years after that, SDGFP held its first lion hunting season, with a quota of 25 lions or 5 females, whichever came first.

Despite pleas from lion activists and protests by noted researchers, SDGFP biologists have proposed increasing the quota each year. At first, the proposed increases referred to lion population reduction, but lately the focus has shifted to anticipating and satisfying the desires of the state game commission. For three years running (2009-2011), SDGFP officials assumed that the commission would want an increase over the previous year’s quota and thereby proposed one. And each year the commission took SDGFP’s proposed quota and raised it.

The commissioners have given the same excuses for their actions every year by continually challenging SDGFP’s lion population estimate and finding “testimony from hunters and landowners was too compelling to ignore.”

By 2012 the proposed kill had reached 70 lions or 50 females. 73 lions were actually killed before the three-month (January-March) hunting season closed early.

The commission’s even larger proposed quota of 100 lions or 70 females for the 2013 season was quickly justified by SDGFP biologists on the premise that they miscalculated earlier lion population projections, and now believed that instead of 200 lions, South Dakota had 303: 45 adult males, 87 adult females, 33 sub-adult males, 35 sub-adult females and 103 kittens. Neither SDGFP nor the commission commented on the potential orphaning of kittens if 70 of the state’s estimated 87 remaining adult female lions were killed as proposed.

In Conclusion

It seems as if every year the hunting quotas for mountain lions go up and agencies are less certain about the number of lions living in their states, while quite sure that the populations are healthy and growing. High mortality levels are used to justify higher limits the following year. It’s a strange and unscientific circular argument: we killed more lions last year, so there must be more lions this year. The science of lion population modeling by state game agencies appears to be based on the premise that lions must be doing okay because hunters are killing so many.

We know that there are fewer lions remaining in the entire United States than there are people living in many of the rural towns that so fear and resent them: surely less than 50,000—and likely several tens of thousands less. It’s this vast uncertainty that agonizes conservationists. In the governments’ game of sleight of hand, the lion’s always the loser.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email