“We need to chase these animals and make them afraid of us… – Nebraska Game & Parks Commissioner Stacy Swinney

If you’ve kept up with our blog or Facebook pages, you know that Nebraska Game and Parks (NGP) Commissioners in May reviewed public testimony and written comments to the state’s first proposed cougar hunting season, a proposal that would have taken an arguably sustainable (if sustainable, we might support it) two males or one female from the estimated 15-22 cats now calling the Pine Ridge National Forest in the Nebraska panhandle home.

Though an easy majority of public testimony from the Panhandle and written comments to the plan, taken together, opposed the hunting measure, Commissioners ordered their biologists to rewrite the agency’s proposal.

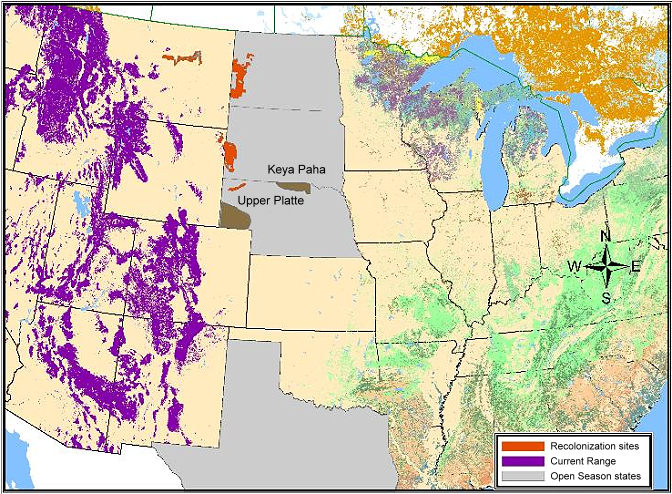

The revised 2013 Recommendations for a Mountain Lion Hunting Seasonreleased in July doubled the Pine Ridge take and split the hunting season in two, making sanctuary regions with developing cougar presence, the Keya Paha and Upper Platte, while opening up 85% of the rest of Nebraska (habitat considered unsuitable by NGP) to an unlimited, year-round hunt. After hearing testimony on the revision in Lincoln, and reviewing another 90 written comments, Commissioners passed the new proposal unanimously on July 26th.

Aside from the nominal nod to provide a recreational opportunity for 100 lottery hunters, the expressed management goal, by raising the take to 18% – 27% of the estimated population (14% of mortalities, matching the average reproduction rate, is considered the limit of sustainability), is to reduce those 20ish cats in the federally owned Pine Ridge National Forest. Why?

The Recommendations conclude with this sentence:

“The Commission intends to manage mountain lion populations over time with consideration given to social acceptance, effects on prey populations, depredations on pets and livestock, and human safety.”

Problem is, NGP has conducted no public attitude surveys to measure the social acceptance of cougars, the effects of cougar predation on prey species appear nowhere in any of the agency’s deer reports, nor has there been any documented incidents of pet, livestock or human predation in 20 years of cougar dispersal/recolonization in Nebraska.Absent any examples in the Recommendations of the “considerations” purportedly informing the Commissioners’ intention to manage cougars, one wonders on what evidence they based their decision to launch an inaugural hunt.

Apparently, that decision turned not on prey impacts or human safety or 20 years without a predation incident in Nebraska of any kind, but on fear. Although state regulation already permits anyone to defend livestock, property and themselves from cougars, testimony by Panhandle residents in May who reported living in fear was weighted more heavily than written comments and testimony prior to the final vote in Lincoln, testimony that ran 7-2 against the hunt (one Commissioner testified in favor). Of the roughly 90 written comments submitted, only 3 supported the hunting measure (and just 2 were from hunters). At least 57 of the more than 80 opposed resided in Nebraska (some provided no address). Since public testimony and written comments were the only instruments cited to gauge the Recommendations’ “social acceptance,” it would appear that the acceptance for cougars among Nebraskans from these limited samples already approaches the kind of majority percentages we see in states with long established cougar populations.

But if you listen to Commissioner Stacey Swinney, who mentions an escalation (without examples or data) from “mountain lion concerns to mountain lion issues to mountain lion problems,” fewer than 20 residents near Pine Ridge set the cougar hunting policy for the entire state of Nebraska. A responsive state game commission might counter public fears with public education (solid material NGP has already produced, some of it specifically for the Commissioners), not an inaugural predator hunting season fed by fear and grounded in boogeyman scare tactics.

Instead, and despite mentioning testimony citing the Washington State University (WSU) studies on the destabilizing effects of cougar sport hunting that the Cougar Rewilding Foundation and other advocates provided the Commission, it appears to NGP Commissioners that sacrificing breeding females and trophy toms is the only way to counter public fear. Why?

Not because it can minimize a record of absent conflicts. Taking out the animals that cause the least amount of trouble — trophy toms and moms achieve breeding age by avoiding pets, livestock and people, behavior females teach their young — will give constituents the impression that NGP is “doing something.”

This is a frequent refrain, the entrenched fantasy among game managers, hunters, and ranchers that it’s simply a matter of time before conflicts rise and a child is picked off, ignoring both decades of actual experience and 21st century peer-reviewed cougar management. So, the reflex masquerading as management goes, fight fear with fear and start killing, though random removal by hunting cannot select for problem individuals: a dead cat learns nothing. (A detailed search yielded not a single study demonstrating that hunting works as a livestock deterrent or public safety measure). Taking out problem individuals at the source remains the most effective control. Since a cougar has yet to be implicated in Nebraska in any kind of pet, livestock or human depredation, where does Commissioner Swinney’s perceived cougar problem come from? Perhaps the manner in which Nebraska handles its residential cougar incidents, a number of which have occurred in towns and cities in the Panhandle, has something to do with it.

19 cougars have been taken out since 1999 under Nebraska’s “zero tolerance” residential policy (p. 10, 4.4.1). None were implicated in an attack or depredation. These are typically young, dispersing cats temporarily sidelined in a neighborhood or near a ranch, treed by a dog (a treed cat is seeking refuge; it’s afraid) or bedded down, suddenly sighted and reported to the authorities, when all hell breaks loose. The cat becomes cornered in a maelstrom of people, media, and first-responders, lights spinning and sirens wailing, ending in a hail of gunfire, an often widely reported scene that reinforces the impression that protecting the public from cougars requires nothing short of a SWAT team. It doesn’t. Some state cougar managers and the experts who collaborated on Cougar Management Guidelines understand that — unless the cat has been implicated in a depredation — the safest thing to do is pull back the public and the media, create escape routes for the cat and wait it out, before hazing or tranquilizing if the cat fails to move on its own (see Kertson’s perceived risk vs actual risk).

Discharging firearms amid residences is the last thing responsible first-responders need to do. Just ask New Jersey Fish and Wildlife and its army of municipal first-responders, who routinely handle suburban black bear complaints under strict management protocols (p. 17-20). But letting cougars go with little incident doesn’t appear heroic, isn’t simply the best, safest practice, doesn’t leave the impression that officials are “doing something.” Even tranquilized, captured cats are automatically killed for simply showing up in a Nebraska municipality. Clear, experienced heads can and do handle marooned cougars without spectacle.

Under the new hunting policy, Nebraska Game and Parks may soon find itself tracking down and euthanizing orphaned kittens, while devoting increasing time and increasing resources to pet, livestock and human conflicts caused by targeting trophy adults. They may find themselves dealing with the management consequences of destabilization detailed by WSU, the kind of consequences South Dakota has been corralling for several years. Incidents the WSU research predicts like this one, where a female with kittens may have sought refuge along the residential interface from roving subadult males bent on killing the kittens of breeding toms taken for trophy.

And, with an open season declared across 85% of the rest of the Nebraska — matching similar policies in the Dakotas and Texas — leaving all but Kansas and Oklahoma (states where breeding has yet to occur) providing protection on the Plains, the stage is set for a virtual dispersal gauntlet across the Prairie States.

Yet, this widening firewall goes unreported by one news source after another — including the New York Times — who continue to describe eastward recolonization as a done deal.

Portraying the immanence of an eastern recovery fraught with conflict, Guy Gugliotta’s A Glamorous Killer Returns burnishes its feline fatale headline by guilding the record of cougar conflict: the suggestion of “emigrants” attacking people; there are no documented attacks east of the Rockies since the middle of the 19th century.

“Increasing numbers make them harder to manage — and harder for people to tolerate;” No, as both WSU and California have determined, less cougar management is more, and every public attitude survey we’ve looked at in states coexisting with cougars show that the public likes having cougars around by wide majorities.

Gugliotta also suggests that a handful of resident cougars (who can purportedly “wreak havoc on other wildlife”) caused the bighorn population in Arizona’s 665,000 acre Kofa National Wildlife Refuge to drop from 800 in 2000 to 400, where the population has hovered since 2006: cougar impacts on the Kofa bighorns remain in dispute after years of conflicting research.

Finally, Gugliotta hacks up this gasping chestnut, “There are increasing reports of sightings in 11 Midwestern states.” Every cougar biologist and state game agency (including 15 years from our own monitoring) knows that sightings are no indicator of presence.

Even confirmations from physical evidence (shy of distinct individual markers) are no litmus test for density. A single cat can leave multiple sign across hundreds of miles, like this one wearing a radio collar who tripped random remote cams across northern Wisconsin and the Michigan Upper Peninsula, leaving the impression of multiple cats on the landscape.

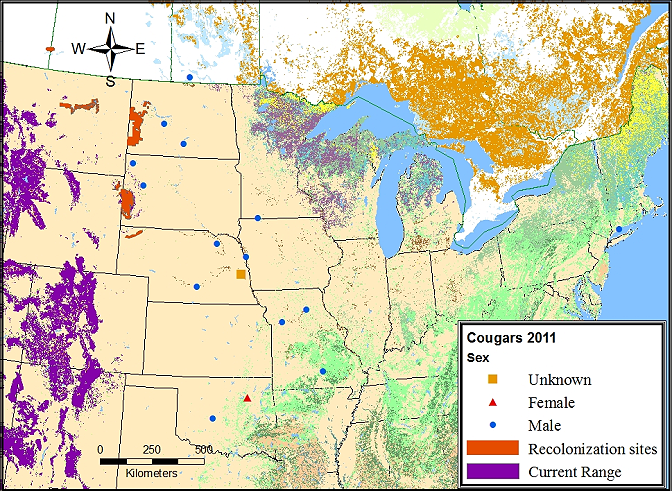

More significantly, the number of mortalities and captures—concrete indicators of individual cats—east of the source colonies has begun to drop. As we noted last year, mortalities and captures had risen every year since 2000, peaking in 2011, when we recorded 16 such incidents.

However, as we predicted, that number dipped for the first time in 2012, to 9, including one from December in Osage County, Oklahoma (p. F-3) that we learned of this Spring, a female removed by Wildlife Services for calf depredation. She was the lone female documented east of the source populations in 2012, and only the second female to have turned up in Oklahoma. Again, no females, no recovery.

In more than 20 years of dispersal, a wild female or kittens have yet to be documented in a Midwestern state east of the prairie colonies. That fact went unreported by Gugliotta (we contacted the Times regarding its nest of errors; we received no response), and continues to go entirely unnoticed by journalists and game officials, and unmentioned even by our friends and colleagues at the Cougar Network (CN). With all due respect, CN’s glutted map featuring every confirmation since 1990 and widely cited, dated data (ending in ’08) haven’t accounted for the sharp rise in colony hunting quotas backed by open seasons on the eastern prairies, and remain the primary sources for the illusion of eastward recolonization.

Mortalities and captures tend to spike in the second half of each year. So far, in 2013 there have been 2. Despite recalibrating last year its Black Hills’ estimate up to a controversial 300 cats, South Dakota’s 2013 female hunting subquota of 70 fell short by 1/2 — the fourth consecutive year they failed to reach the female subquota (scroll to 5:00 for harvest graph; combined WY/SD Black Hills’ harvest impacts at 18:00). The Black Hills’ population is getting hammered on both sides of the Wyoming/South Dakota state line. It’s no stretch to suggest that the number of cougars being killed, captured and confirmed East will continue downward.

An unfettered generation of cougar dispersal East is passing, a generation that couldn’t put a female or kittens near the Great Lakes or in the Ozarks.

With the source colonies being pounded into population sinks, Prairie States bent on stopping eastern pioneers dead in their tracks are slamming the door on the most promising alpha predator recovery story in the world.

In the United States, it’s a story half-finished.

Christopher Spatz

Maps by John Laundré

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email