Smoke Bomb & Backhoe Cougar Management

Guest Commentary by Christopher Spatz, President of the Cougar Rewilding Foundation

Wall, South Dakota. If you’ve driven I-90 anywhere between Billings, Montana and Minnesota, you’ve seen the billboards for Wall Drug, a Main Street marketing phenomenon featuring a prairie art museum, shops and restaurants, and the eponymous drugstore. Once described by its founding pharmacist as “the middle of nowhere,” Wall Drug draws 2 million visitors a year to the town of 766 and its 2.2 square miles high on the prairie surrounded by nothing but the spectral, Crazy Horse-haunted Badlands. On December 12th, a dispersing tom likely traversing the adjacent Cheyenne River corridor was spotted within the Wall “city limits,” a move marking him under South Dakota Game, Fish & Parks (SDGF&P) guidelines for immediate execution.

The cat disappeared into a hole. SDGF&P officers dispatched to the scene began dropping smoke bombs into the cat’s temporary shelter. He didn’t flush. The town employee who first sighted him arrived with a backhoe and began excavating. As the cowering cat, “very much alive,” was uncovered, SDGF&P officers shot him. He was 2 years-old and weighed 91 lbs.

Here’s what we know about cougars temporarily treed or pinned-down in residential areas and their risk to the public: Not one has ever attacked a resident or a first-responder. Ever.

They aren’t in fight-defense mode. They want out. Running or treeing are their instinctive routes to safety. California, where 38 million people are coexisting with 5,000 cougars, enacted Senate Bill 132 authorizing the California Department of Fish & Wildlife to “use only nonlethal procedures when responding to reports of mountain lions near residences that do not involve an immanent threat to human life.” California defines “immanent threat to public health or safety” as, “a situation where a mountain lion exhibits one or more aggressive behaviors directed toward a person that is not reasonably believed to be due to the presence of responders.”

Killing cougars temporarily marooned within town limits are not better-safe-than-sorry situations. Decades of experience reveal otherwise, and that experience highlights the problems of perceived risk vs actual risk with respect to wildlife management and protecting the public. As noted in this Austin article about a cougar incident at Big Bend National Park, the more familiar we are with something, the less risky we perceive the threat. Let’s compare the actual human threats from cougars with those of the biggest, most familiar human killer: deer. And let’s look at South Dakota.

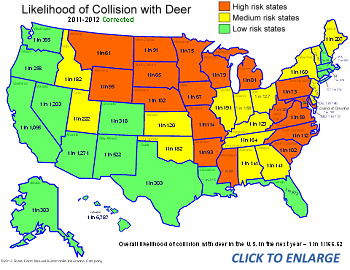

We’ve gone over these numbers before, but they’re worth recounting. Nationally, vehicle collisions with deer injure 30,000 and kill 150-200 people in the United States every year, causing nearly $6 billion in auto-crop-forest-residential damage, medical and mitigation costs. Deer are an acutely real multiple public threat. South Dakota ranks 4th (down from 2nd last year) in the nation in deer vehicle collisions. A 2003 study logged 4,433 deer vehicle collisions in 35 eastern South Dakota counties (66 counties in the state).

Averaging 4-6 cougar contact incidents (“attack” is a misnomer; almost all such incidents involve predation) a year in the US/Canada (the average drops even more when Canada, where Vancouver Island alone significantly pads incidents, is removed from the equation), just 3 people have been killed by cougars in the US since 1998; none since 2008. During the same 15-year period, 450,000 have been injured in the United States and 3,000 have been killed by deer. A cougar has not been implicated in a human-related incident east of the Rockies since the 1850s.

The chance of colliding with a deer in South Dakota is 1 in 65, exceeding the risk of Mid-Atlantic states with notoriously higher deer-densities like Virginia, Pennsylvania and New York . The chance of making contact with a cougar in the western United States is 1 in 775 million; 1 in 3.4 billion for the entire country. As there have occurred no documented human-cougar incidents in South Dakota, the statistical risk is closer to 0.

Given the far greater public safety risk from vehicle collisions with deer, why does South Dakota not have a termination policy for deer encountered within city limits, as it does for cougars?

Why does no state have a comparable, zero-tolernace policy for residential deer? Real question, one I posed to SDGF&P Secretary Jeff Vonk, who replied, “. . . for the record, we do work closely with any city in SD that requests assistance to “terminate” excess deer within city limits.” Meaning every residential deer is not relentlessly hunted down with smoke bombs and backhoes — by any means available — though the public safety risk is well-documented (1 in 166 US deer collision chance on the State Farm map) and, unlike cougars, always immanent.

The young tom sacrificed in Wall would have left the city limits in a blink, but South Dakota’s open season beyond the Black Hills would have left him a marked-cat, marked, as the rash of killings that closed 2013 east of the Prairie colonies attests.

Trickle Down: Cougar Dispersal East Dropping

Dakota hunting quotas and open-season prairie hunting policies continue to limit the number of eastward dispersers measured by mortalities and captures. Before November there was just one mortality/capture, a Nebraska female accidentally killed in a cable restraint trap in January near Scottsbluff.

That’s 8 mortalities/captures for 2013, down from 9 in 2012, and 16 in 2011, the highest total since 2000. And while the number of female kills rose (another female was trapped just west of Pine Ridge, NE on 12/20), none occurred east of the Missouri River. Since 1990, a wild female cougar — dead or alive — has yet to be documented east of the Prairie States.

If there are any bright spots to emerge from the killing zone, it happened in the Midwest. The UP poachers were arrested and charged with killing a protected species. If convicted they could face up to 90 days in jail and a fine of $2500. Because none of the cats documented in the Midwest over the years have been older than 2, we have long suspected that wolves and/or poaching are taking out all of these sub-adults. However, this is the first public incident of alleged poaching.

In Illinois, a dispersing male seeking shelter under a farm corn-crib faced execution when the IL DNR Conservation officer investigating the scene consulted with the farmer.

Cougars are not protected in Illinois, and although the cat had done nothing but traveled 800 miles looking for a girlfriend, the farmer requested that he be shot.

The incident gained the attention of the Chicago Tribune, who offered a sane and humane editorial, suggesting not only that cougars needed protection in Illinois, but wolves and black bears do as well.

Our commendation to the Tribune’s editorial board made their Voice of the People page. A piece by IL DNR director, Marc Miller, quoting former CRF intern Julia Smith’s Illinois predator habitat graduate thesis soon followed, suggesting that there is room in Illinois for apex predators.

We tapped the good vibes to offer IL DNR our Cougar Ecology and Incident Management Course for First-Responders, but after expressing interest initially, IL DNR declined. However, we’re still pursuing contacts in Illinois to schedule our next class.

Trouble With Ernie

A lone legislative voice to appear for cougar protection on the Prairies is Nebraska state senator Ernie Chambers. A 9-term legislator from Omaha who regained his seat after losing it under a term-limit provision, Nebraska’s cougar hunt was ratified during Chambers’ absence. He was re-elected in 2012 and returned with his sights set on, among other things, repealing Nebraska’s inaugural 2014, two-part hunt of 22 cougars in the panhandle’s Pine Ridge National Forest.

As the first half of the season opened January 1st and the 2-male quota was quickly reached, Chambers argued that the season should have been closed in December when a female was incidentally killed on 12/20 in a trapper’s snare near Pine Ridge. Meeting the female sub quota of 1 would effectively close either season. Chambers introduced Legislative Bill 671 (LB 671) to repeal the hunt on January 8th.

Dawes County Commissioner Stacey Swinney (we previously misidentified Swinney as a Nebraska Game & Parks Commissioner (NG&P); thank you to NG&P biologist Sam Wilson for setting us straight) traveled to Lincoln and met with Chambers, advocating hunting as behavior modification (both the Dakotas and Nebraska have yet to document a single cougar livestock depredation or human incident in 30 years of recolonization), “If we can make them run from us, then half the battle is won,” the kind of anachronistic management phantasy that continues to misinform anti-cougar legislation.

Robert Weilgus of Washington State University’s Large Carnivore Conservation Lab, who’s peer-reviewed research on cougar social dynamics has restructured Washington State’s cougar hunting policy (research we’ve sent to Sam Wilson and NG&P Game Commissioners), chimed in on the Nebraska hunt, suggesting that, “Hunting a population of less than 30 animals is just crazy . . . They can blink out. It’s just like rolling the dice.” The pair of males taken in January illustrates the potential for conflict Weilgus has warned of, “The bottom line, if you’re a rancher in lightly hunted population, you’re dealing with one male cougar. If you’re a rancher in a heavily hunted population . . . now you’ve got three guys you’ve got to deal with.”

Mature toms won’t tolerate younger males in their territories, gaining their maturity by avoiding pets, livestock and people. Young, marauding males will find and kill their hunted competitor’s kittens, which can push females with litters into residential areas seeking sanctuary.

Chambers’ legislative repeal isn’t without its problems. Prior to the hunt, Nebraskans already had the right to defend themselves, their pets, livestock and property from cougars, a protection that many cougar advocates feel makes the hunt unnecessary. LB 671 would also repeal the ability to self-defend. That provision could be a deal-killer.

Chambers’ LB 671 made it all the way to Governor Heineman’s desk, but was vetoed. In his veto letter, the Governor stated, “I am concerned that LB 671 is potentially unconstitutional as it prohibits wildlife management of mountain lions through hunting.” In 2012, Nebraska amended its constitution to specify, “hunting, fishing, and harvesting of wildlife shall be a preferred means of managing and controlling wildlife.”

Frustrated but still motivated, as the 2014 legislative session came to a close, Senator Chambers vowed to return next year to try once again to protect the state’s tiny population of mountain lions. In his own words, “the war is not over.”

Southern Panther Death’s Down, For Now

Panther deaths in 2013 totaled 20, down from 2012’s record 27. 15 were road-kills, also down from 18 the previous year. 21 kitten births were documented.

A bother-sister pair of orphans raised in captivity were released successfully last year to separate areas. Released in January to the Picayune Strand Forest in Collier County, the female gave birth to a kitten in June.

While this could have been a perfect opportunity outlined by the USFWS in 2012 to seed a new population north of the female-stopping Caloosahatchee River, the pair were returned to saturated panther habitat. The young male, especially, faced a precarious recovery released along territory patrolled by mature toms.

On December 11th, another panther habitat protecting lawsuit led by the Center for Biological Diversity was filed to halt a proposed 970-acre limerock and sand quarry upstream from wetland preserves, wetland flowway and through a wildlife corridor. In more than 40 years of federal listing as an endangered species, not a single development proposal in panther habitat has been stopped.

Carnivore Conservation Act

Eastern coyote researcher and author, Jonathan Way, and Justice for Wolves’, Louise Kane, have gotten the jump on what many besieged predator advocates have been considering through this Dark Age of predator policy decisions: A Carnivore Conservation Act that would do for carnivores what the Migratory Bird Act did for raptor protection and recovery. In particular, the Act amends abuses and contradictions to existing carnivore hunting regulations built on the North American Wildlife Conservation Model.

First proposed for Massachusetts in March, 2013, Way and Kane’s Act will:

- Promote the welfare of carnivores by prohibiting cruel and inhumane hunting practices. This includes: Prohibiting penning of wildlife for purposes of training dogs or as spectator sport; Prohibiting hounding (i.e., using dogs to chase) carnivores; Extending the provisions of the MA anti cruelty laws to wild carnivores.

- Promote a fair-chase hunting ethic of carnivores. This includes:Prohibiting baiting for purpose of killing carnivores; Prohibiting shooting carnivores from inside a home or building; Prohibiting night hunting; Prohibiting the use of electronic calls.

- Require scientifically valid carnivore management practices that serve a legitimate management purpose/objective/goal. This includes:Prohibiting wildlife killing contests or predator derbies; Creating a quota for carnivores; Requiring the purchase of a carnivore hunting tag and creation of a minimum fee for hunting carnivores; Reduce season hunting lengths; Establishing no hunting refuges on state and federal park and forest lands; Mandating training for wildlife specialists that “remove” carnivores for management purposes; Requiring good animal husbandry practices to prevent carnivore livestock conflicts; Creating a wanton waste provision for carnivores similar to other game species.

- Require the use of current and best available science in wildlife management decisions of carnivores. This involves abandoning principles that support the maximum utilization or killing of carnivores and requires accounting for the ecological importance of carnivores in fully functioning and robust ecosystems and recognizing their innate social and family structures.This includes: Obtaining scientific research permits without political interference; Recognizing and identifying eastern coyotes also as “coywolves” (Canis latrans x C. lycaon) in order to recognize their mixed species (western coyote x eastern wolf) background; Creating a carnivore conservation biologist position to focus on non-lethal management objectives for carnivores and to study and promote tolerance of carnivores.

Way and Kane hope to take the Carnivore Conservation Act national.

Way and Kane hope to take the Carnivore Conservation Act national.

Here, here!

Christopher Spatz

Cougar mortality statistics provided by Helen McGinnis. Cougar incident statistics provided by John Laundré

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email