Mishka: Washington Fish and Wildlife’s first bear dog retires after 12 years of faithful service

Mishka: Washington Fish and Wildlife’s first bear dog retires after 12 years of faithful service

This story was written by Annette Cary, and posted by the Tri-City Herald on March 19, 2015.

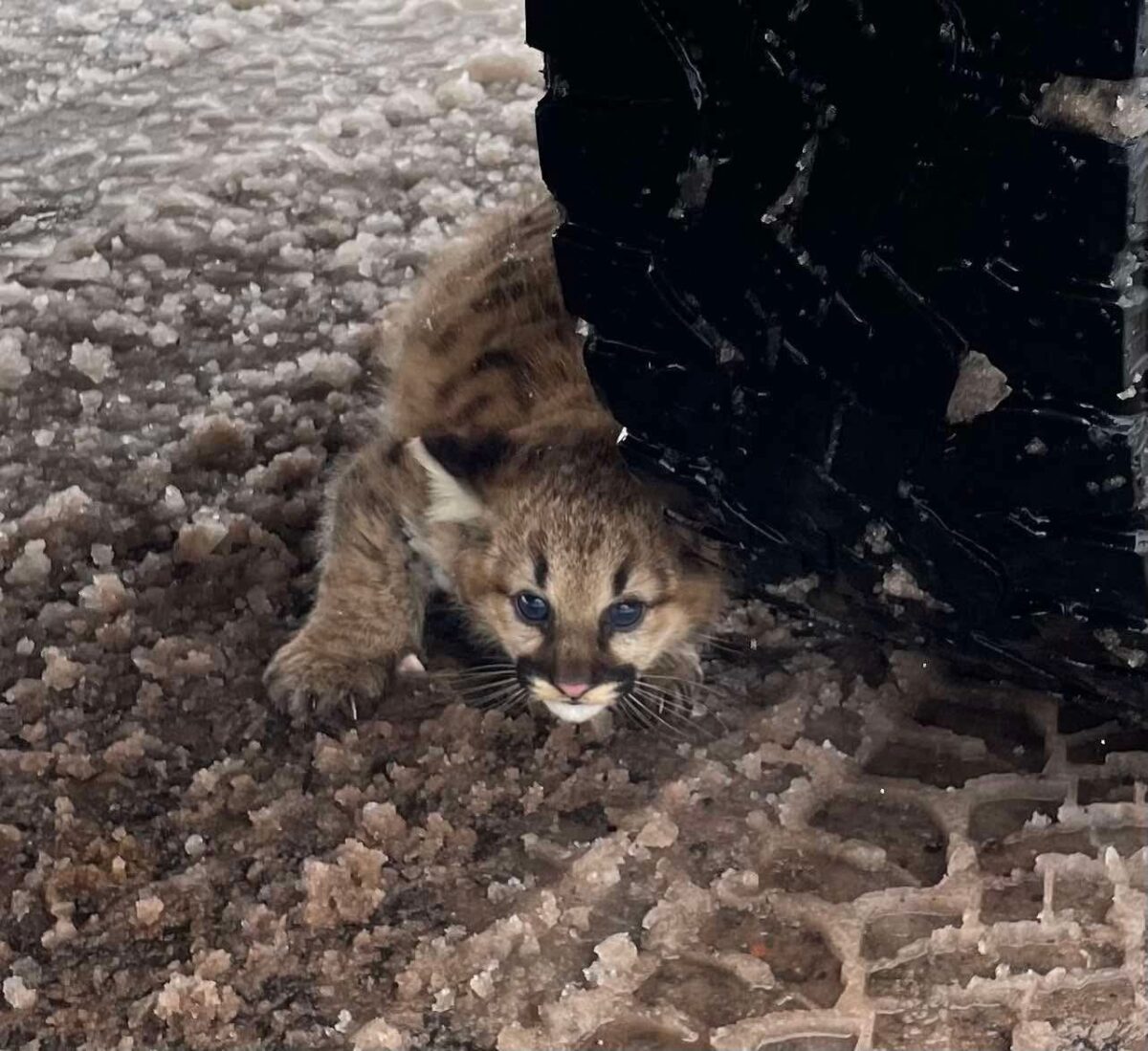

While the following story refers mostly to bears, Mishka and his fellow Karelian bear dogs are similarly used to deal with wayward cougars

Washington’s first Karelian bear dog likely has harassed his last bear and sniffed out the wild game bones left behind by a poacher for the final time.

Mishka, after serving the state for 12 years, is headed to a life of leisure after a retirement ceremony Thursday in Kennewick.

He lives on the west side of the state with his handler and owner, Fish and Wildlife officer Bruce Richards, but was honored in Kennewick as the agency’s officers gathered there for training this week.

Mishka is part of a breed that is instinctively bold with bears and can be trained to track, help capture and then discourage bears from returning to places where they can get in trouble with people.

Mishka solves more bear problems in a year than most officers can in a career, Richards has said. He also is retiring after 41 years with the agency.

The black and white dog started working with biologist Rocky Spencer, helping with cougar research. He would find the carcasses of prey killed by cats being tracked with state collars.

After Spencer died in a helicopter accident, Richards took over his care in a pilot program to see if Karelian bear dogs could be used in game enforcement programs.

“(Mishka) was very good at finding dead bones,” Richards said.

The dog’s first test in the enforcement program was to see if he could locate the bones of a poached elk that state enforcement officers had heard about in the Olympic National Park. They had been unable to find the carcass over the course of a year.

Richards took Mishka on a three-hour hike to an area of the park where the elk was believed to have been shot. Then Richards took the dog’s halter off, a signal that he was working.

Fifteen minutes later, Mishka was back with an elk bone. He had dug below some leaves in a rocky area that would have been difficult for Richards and other officers to search. A bone with saw marks also was discovered, helping wrap up the case.

“He makes one big game case a year usually,” Richards said.

At home with Richards, Mishka is gentle with the orphaned wildlife that Richards’ wife will sometimes bottlefeed for a few days for the Fish and Wildlife Department.

At home with Richards, Mishka is gentle with the orphaned wildlife that Richards’ wife will sometimes bottlefeed for a few days for the Fish and Wildlife Department.

“Fawns go up to Mishka and he adopts them,” Richards said.

He has been socialized to be good with kids. One of Richards’ favorite memories in his years with Mishka was seeing a small boy with spina bifida staring at the dog, obviously entranced, at the state fair in Puyallup.

Richards said the boy, who was not much taller than Mishka, could take him for a walk. The obviously happy child spent 20 minutes slowly and haltingly making his way in a circle around a table, holding Mishka by the collar.

A bear provokes a different reaction from Mishka than the tender side he shows to children and fawns.

“He will go nose to nose with a bear,” Richards said.

Karelian bear dogs are used by the state to track bears and cougars. They hunt like a wolf, tracking and then circling their prey. The dogs are so agile that they can bounce around and evade the attack of a dangerous animal, Richards said.

Mishka and other Karelian bear dogs help harass captured bears as they are released. In a “hard release,” a bear may be shot with rubber bullets and the dogs released to chase it, re-introducing a fear of civilization to the bears.

“Bears are very, very smart and can be taught to stay away from people,” Richards said.

Richards estimates that at least 80 percent of bears trapped and released with the assistance of Mishka avoid becoming repeat offenders, which can lead to them being killed.

Mishka also has been used to confirm that no wild animal is in an area.

In one early case, Richards was called out at night after a couple showed up at Puyallup hospital needing multiple stitches. They had been attacked by a cougar, they said.

But when he and Mishka reached the spot where the couple said they were attacked, Mishka’s hair did not stand up like it does if a cougar is in the vicinity. He ran around like he was chasing rabbits rather than hunting a cougar, Richards said.

When they went back to the couple’s house, they found the couple’s white pit bull in the backyard, covered with blood from attacking its owners.

Without Mishka indicating that there was no cougar, officers could have spent weeks trying to find the nonexistent cougar, and the community would have panicked, Richards said.

Karelian bear dogs were bred for hunting in Finland, where they have been regarded as a national treasure. During World War II Russians killed them, reducing their population to less than 100, Richards said. Today, there are about 400 in the United States.

Mishka came from the kennel of a Florence, Mont., dog breeder, Carrie Hunt. She had traveled to Finland and brought a pair home to the United States to try to save the grizzly bears that were being killed because they became too comfortable around humans in national parks, including Glacier National Park, Richards said.

Mishka can be a handful, Richards said.

“They are called the mule of the dog world – very smart, but very independent,” Richards said.

“The hardest thing to do is teach them to come. They want to go,” he said. He cannot leave a car window unrolled. If Mishka sees something to chase, he’ll be out the window.

However, Mishka is slowing down now. The last time Richards and Mishka were out in the woods, Richards had to lift the dog over a log. His dog is ready to sit in the truck these days, Richards said.

“Mishka has served Washington wildlife enthusiasts well and has more than earned retirement,” he said.

Fish and Wildlife will continue to use five other Karelian bear dogs to help with research, haze bears, assist investigations and locate injured and orphaned wildlife. Three are based in western Washington and two others are based in Wenatchee, where they are used mostly for research.

Other states are considering using Karelian bear dogs in their wildlife enforcement programs, thanks to the success of Washington’s program, Richards said.

Information about how this program began was featured in Barking Up the Right Tree: Washington’s Karelian Bear Dog Program, and listen to our interview On Air with WDFW Officer Jones about the daily life of a warden partnered with a karelian bear dog.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email