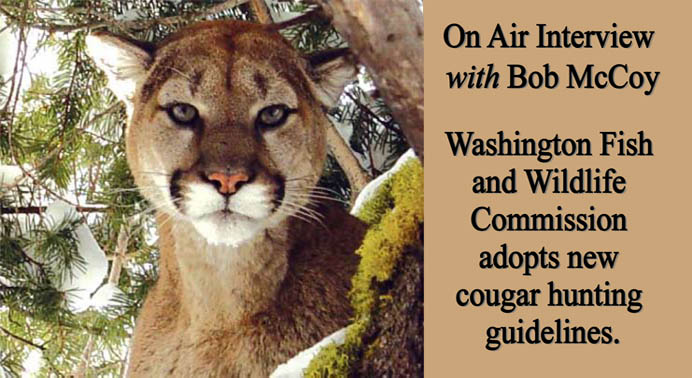

On Air with Bob McCoy

An Audio Interview with Julie West, MLF Broadcaster

Listen Now!

Listen Now!

Listen to the interview from MLF’s ON AIR program, podcasting research and policy discussions about the issues that face the American lion.

Transcript of Interview

Intro: [music] Welcome to On Air with the Mountain Lion Foundation, broadcasting research and policy discussions to understand the issues that face the American Lion.

Julie: In April, 2020, the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission adopted new cougar hunting guidelines. The nine-member commission, composed of citizens appointed by the governor, sets policy for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Here to speak with us about the commission’s decision is Bob McCoy. Bob serves on the Board of Directors with the Mountain Lion Foundation, and has dedicated the last decade to issues affecting cougars, bears and wolves. For more information on Bob, see his bio in the article accompanying this podcast on the Mountain Lion Foundation website. So Bob, hello, welcome.

Bob: Hi Julie, glad to be here.

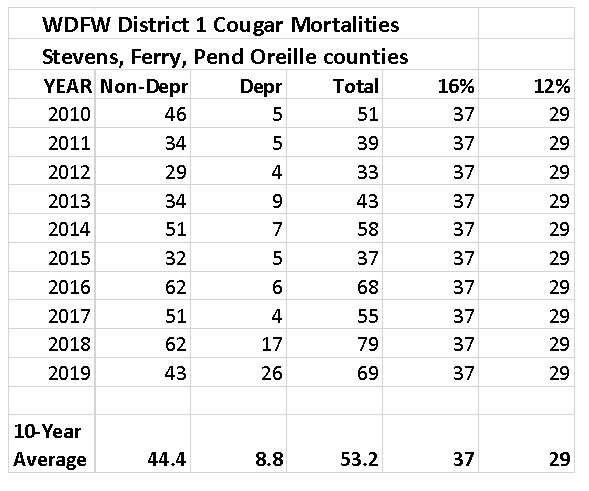

Julie: Science research shows that over harvesting cougars exceeds the threshold of sustainability for their populations, disrupts their social order and territories, and creates conflicts with humans and domestic animals. You along with some scientists and concerned citizens have said that the new WDFW or Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife policy exceeds this threshold limit, what is the new policy and why is it potentially dire for cougars?

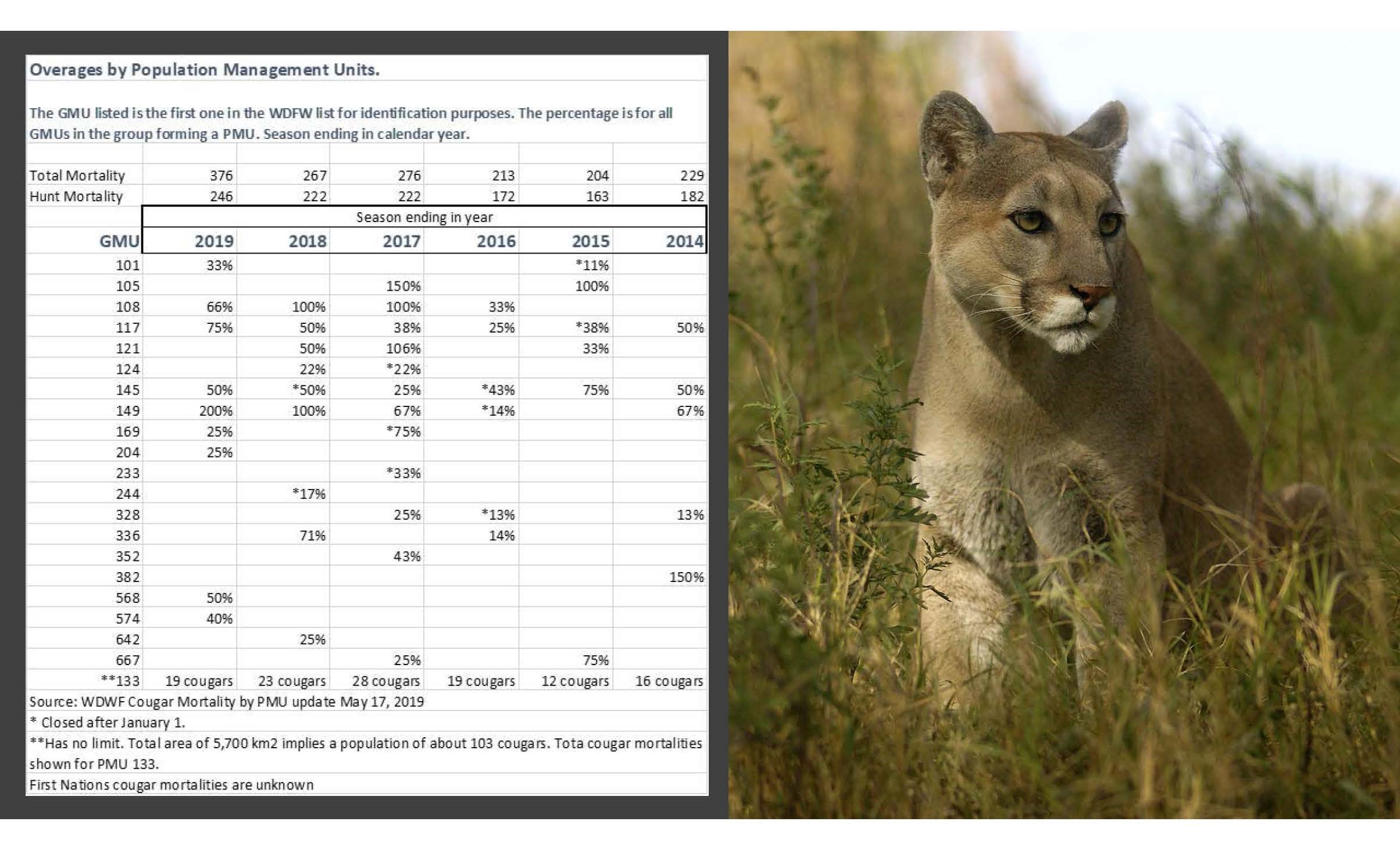

Bob: Okay. Under the new rule, only the estimate of adult cats are used to calculate the 16% upper guidelines. Additionally, any area that exceeded the 16% guideline, at least once in the past five years, now uses the highest value as the new guideline. Even worse for the cougar population, kittens and juveniles killed by hunters will not count towards fulfilling that guideline or closing a hunt area. And since hunters will still kill juveniles and kittens, with no upper limit, young cats have no protection under the new rule. It’s a violation to kill a spotted kitten, but killing one does not count toward closing an area. So they increased the relative size of the population and did not allow any sort of safety margin for unforeseen events: forest fires, lack of prey due to either warming effects or fires, or encroachments by humans. So they took a very liberal approach to hunting cougars.

Julie: Are depredation factors considered in that, like if a cougar wanders into someone’s backyard and causes a public safety concern and needs to be killed, for example, how, how did those kinds of numbers relate to the new guidelines?

Bob: Well, originally when the studies were done, cougars killed for reasons of public safety and livestock depredations were somewhat stable each year. So the department decided not to count those particular kills as going against the 12 to 16% guideline. That way the department would not appear to be competing with the hunter for the ability to kill a cougar. One other thing that the Department did, which is very concerning, is the Department decided in the first four months of the hunting season, September through the end of December, that they would not enforce any upper guidelines or any upper limits on cougar mortalities. So in certain parts of the state, especially the Northeast counties, Stevens, Ferry, and Pend Oreille, they consistently killed more than 16% of the cougar population. This was basically what started creating more conflicts. There’s been kind of a perfect storm in the Northeast counties.

Julie: I’m confused then, if the commission set an agreed upon range, I guess it’s no longer called threshold, so we’ll call it guideline, and yet there’s the depredation and the extra hunting allowances, as you say are going consistently above that number, then why is it there at all? It almost seems like it’s, it’s not really being considered in any real way, or am I, am I overlooking something?

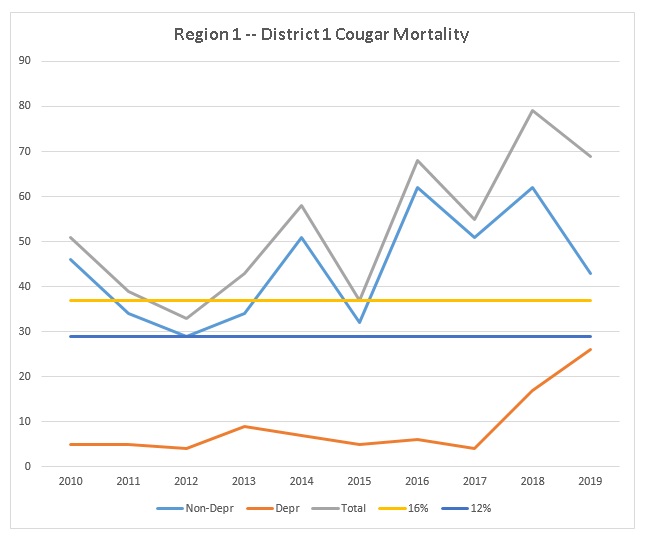

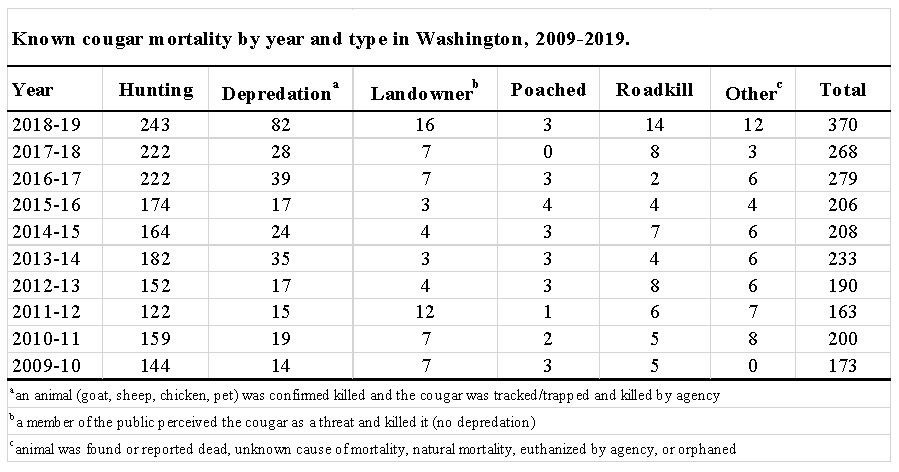

Bob: I don’t think so, Julie. I think that’s fairly accurate. What we have seen in the past few years is that the cougar mortalities in district one, which is essentially the Northeast counties with the total mortality of cougars, has only been within the 12 to 16% range in two of the last 10 years. For instance, in 2018 district one has an upper guideline of 16%, cougar mortality would be 37 cougars, and yet in 2018, the total cougars killed were 79, 62 of those were hunting and 17 of them were for depredations. Then in 2019, the number of cougars killed, dropped down back to 69, 43 by hunting and 26 by depredation. And the depredation kills don’t count against the 16%. So what we’ve seen is a change in sort of the policy, where now sheriffs and specially assigned agents of counties are now going out and killing cougars independently of the department. So we’re seeing a very high increase in the number of cougars killed for so-called depredation and public safety. Essentially it could be a wholesale slaughter.

Julie: If scientists had proposed those numbers with good reason based on the reproduction of females and the number of young cats moving in, where toms had previously existed and creating more conflicts, then it almost seems like the new policy is not founded on science. You have observed and said that since 2011, you’ve seen these decisions moving away from data and more toward rules that favor hunters. This seems like one example of that. Are there other examples?

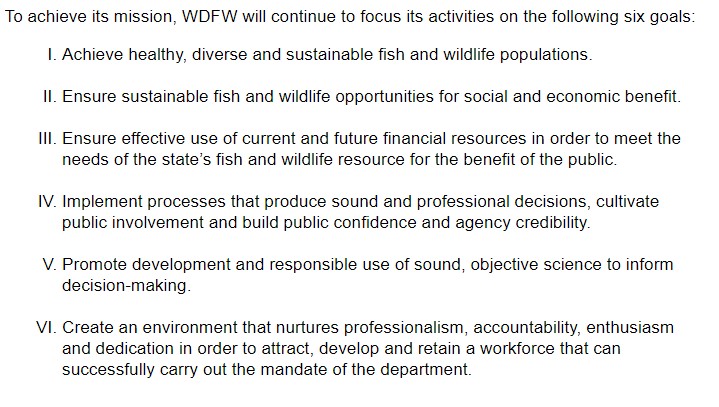

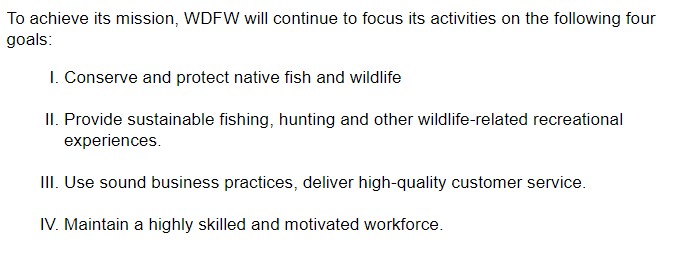

Bob: Yes, there are in fact just in the near term, after this vote was taken by the department, the Chair of the Wildlife Subcommittee of the Commission stated that this decision was made not for the benefit of public safety, but strictly to increase hunter opportunity. So right there is a statement saying that we’re not looking at the science, and because the science pretty much from multiple areas, British Columbia, Colorado, of course Washington, shows that we get increased conflict; but going back to 2011, about the time more than a decade and millions of dollars’ worth of cougar research that had taken place in Washington was starting to be published in peer reviewed journals, the Department of Fish and Wildlife removed the word “science,” and its goal of using best available science in the management of wildlife.

Bob: They had a mission statement, which is essentially to preserve and protect the wildlife resources of the state for future generations. And they had six goals that they would use to accomplish their mission. And one of those goals was to use the best available science in managing the wildlife resources. They removed that goal completely plus another goal, and they reduced it down to four goals. And science has really, in terms of predator management, not mattered. A couple of years later, and I forget the year, the Legislature passed a law that stated that Fish and Wildlife Department had to show the science that they used in making decisions that impacted land owners and hydraulic projects–diversion of streams, damming up creeks, that type of thing. And they explicitly excluded any decisions about managing wildlife. So the Department was told you have to use science, if you’re going to do something that might impact the landowner, but you don’t have to use it, you don’t have to show any science for making wildlife decisions.

Julie: Are there university or independent scientists who are eager to work with the department and share their data?

Bob: Yes, the, the department has sponsored a lot of the university science. They, they work with research biologists out of both the University of Washington and Washington State University. But again, we have a structure where the Commission gives guidance to the Department and they’re not pushing the Department to use the best available science.

Julie: Yeah, it seems like without the science, it would be easy to have special interest groups sway policy. There’s one group that Chair Kim Thorburn referenced multiple times in the April 9th Commission meeting, expressing her enthusiasm for exploring and possibly adopting their ideas. And that is the Northeast Washington Wildlife Group who have been hounding the department to step up their game, pun intended, sorry, on the number of cougars that can be hunted and also destroyed due to public safety issues. What can you tell us about this group and in general, the danger of letting special interest groups dominate the dialogue over science,

Bob: I don’t really know an awful lot about the Northeast Washington Wildlife Group. One of their directors is a former Fish and Wildlife commissioner and also a member of Safari Club International. So right there, you have an impetus toward big game hunting, trophy hunting, and maybe not as much concern about the long term viability of populations, but when the commission was put into its current structure, there was a referendum to the people in 1995 and the referendum essentially said that to keep the commission from being political, they wanted to remove the ability of the Governor of the State to appoint the Director of Fish and Wildlife. So they made the commission responsible for appointing the Director. Hence Governor Inslee will say that he has no control over fish and wildlife. Interestingly enough, the very popular Republican Governor Dan Evans and popular democratic former Governor Booth Gardner both were on the committee against that.

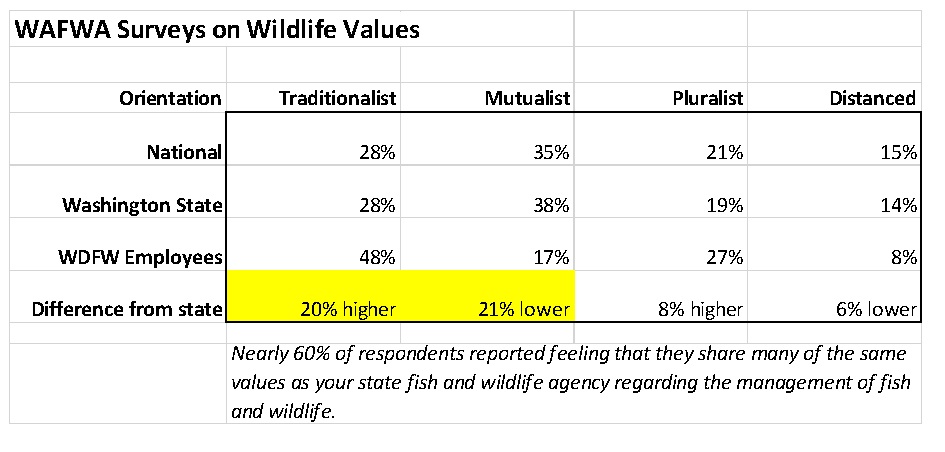

Bob: And they said, if you do this, you will end up with a Fish and Wildlife Commission that answers only to special interests. And the citizens will have no recourse because you can’t call the Governor and say, I’m not voting for you if you don’t change this out. So we have seen a change in that direction. There was a recent study of wildlife values and all, and there were questions of employee views and the employees of Fish and Wildlife Department, their wildlife values are very divergent from that of the citizens of Washington State. And essentially when given a choice between listening to citizens or listening to stakeholders, the employees said that the departments listen to the traditional hunter rather than listen to the citizen. And we certainly saw that in this recent vote by the Commission where probably 600 or so people had spoken out against changing the guidelines and maybe 50 hunters had spoken for changing the guidelines. The Humane Society did a survey that showed that more than 60% of the people in Washington didn’t want increased cougar hunting and the Northeast Washington wildlife group that you mentioned a few minutes ago, they did their own survey. And for some reason, their survey was apparently considered better from the point of view of the Commission than a random survey done by the Humane Society. We have a problem.

Julie: Right. This is more of an aside, but I was listening to an interview with a scientist the other day having to do with climate change. And the scientist said, you know, this is a citizen issue. Not, not just an issue for the scientists, we’re all involved in this together. This is something that concerns us all. So I mentioned that only in thinking of what you said about it’s, it’s more than just an issue affecting hunters, as you said, it really concerns all of the citizens, because wildlife is our entrusted resource, and the cougar is North America’s only big cat that’s what’s so sad to me, it’s the only wild, big cat we’ve got left.

Bob: The African lion, some years back, there were 240,000 African lions. And now there’s probably between 30 and 50 thousand. And you know people are concerned about the African lion and they don’t know about our American lion. What’s interesting is Mark Elbroch out of Panthera recently did a study and the study shows that cougars feed hundreds of different species, and not only hundreds of species of beetles that take root in the carcasses that the cougar leaves, but bears, birds, foxes, coyotes, all types of scavengers. Cougars leave a tremendous amount of meat on the landscape for other creatures. There are studies that show that cougars help to maintain stream beds, and cover bushes and foliage right down to the water’s edge. Deer and elk are very concerned when they’re in cougar territory about putting their face down and just eating. So cougars reduce the amount of time that ungulates will be eating on the landscape, while wolves move them to a different area, but they both end up doing the same thing, which is protecting our riparian areas.

Julie: Nice. Thank you. I am familiar with Elbroch’s research and was fascinated to learn the degree that the whole system benefits from the cougars’ presence. Well, let’s talk about California for a moment because California is the only state that has banned cougar hunting. And as a result, human-animal conflicts in the state have declined and are consistently lower than other states, which seems like a contradiction, but it’s not. What can we learn from California, and these statistics that show that states with the highest hunting allowances are actually the ones with the highest number of conflicts, and the states with the lowest number have fewer conflicts?

Bob: It does tell us that we probably shouldn’t be hunting cougars. Before I go on, I do want to mention Florida has a very small population of cougars. It’s an endangered species, so they don’t hunt them in Florida.

Julie: Thank you.

Bob: There’s no confusion, but of the Western states that have populations, California is the only one that doesn’t hunt the cougar. And in fact, it’s constantly, it appears, working harder to protect them. Mountain Lion Foundation and the Center for Biological Diversity joined together to petition the state to list the mountain lions of the Central Coast and Southern California region as endangered species under California law, and that petition was just approved by the California Fish and Wildlife Commission. So those cougars, Central Coast, all the way down to the Mexican border now have increased protections from being killed for depredations. More emphasis is put on landholders, of livestock owners, the pet owner, to protect their animals. So it’s not an automatic death sentence for a cat. And that’s really important because of the encroachment on cougar habitat and also corridors. So, when we look at various studies, we see that there is a strong correlation between cougar mortalities in one year and human conflicts in the following year. If we look at the studies coming out of Washington State, that said well, as long as you try to keep the mortalities below that reproduction rate of 14%, the cougars should have a relatively stable social environment, social structure, the territoriality will hold, in other words, young cats who might get in trouble, because they’re not as efficient hunting, those cats are kept out. So we have, we have a stable territory. So what we should say is that science says that we could have mortalities of about 14%, not allowing any slack for adverse events, big fires, that sort of thing. So that should be the upper limit.

Bob: Then the next question becomes “well what about the guy who wants to go out and just look at wildlife, doesn’t want to kill it, doesn’t want to eat it, wants to go out and bond with his children. Where do we fit in?” If you remove that 14%, our probability, which is already extremely low of maybe getting to see a cougar in the wild is, is decreased even further. And as it stands now, the Fish and Wildlife Department and the Commission in almost all the states with the exception of California, ignore the equal protection of the wildlife watchers, which predominate. And they give all of the so-called “extra” to the hunters. It’s not right.

Julie: Right. That wildlife is for the benefit of more, more than just hunters. It’s a resource to be enjoyed by all

Bob: Exactly. And the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation that Teddy Roosevelt and Aldo Leopold and bunch of folks started working on these ideas. Some of the statements are that wildlife belongs to all. Wildlife is an international resource. All people should have equal opportunity to wildlife. All 50 States have signed on to those principles, yet we see time. and again, that the wildlife belongs to all is ignored. Wildlife is an international resource is ignored. We not only saw it in this recent, Fish and Wildlife Commission where they just said, well, we received 555 emails, but it just looks like someone just pushed the button and it was a response to a, an action alert. That was still 555 people who took the time to push the button. A few years ago, we had a Fish and Wildlife meeting regarding coyote killing contests, and over who essentially dismissed them by saying, well, as of Friday morning, we’d received 2,000 emails, but it looks like a lot of them were from overseas and the East coast. Well, what happened to wildlife as an international resource, and wildlife belongs to all?

Julie: Do state agencies convene to discuss these issues, and could one state such as California call another such as Washington to task over some of these issues?

Bob: Yeah, there, there is an Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, and then there’s the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. And apparently they do seem to get together and discuss various issues and all, but I’m not really aware of any sort of moral suasion that might take place where California might say to Washington State look, you know, you’re, creating your own problems. Why don’t you do what we do? And when an advocate such as myself testifies or points out California we’re frequently told, well, “we’re not California,” but then they will turn around and say, well, “Idaho has some really interesting ideas on a mountain lion hunting. Maybe we should look at what they’re doing.” Well, we’re not Idaho. I don’t understand other than California is progressive in its management of, especially of, mountain lions. And it goes against the grain of our Fish and Wildlife agency whose basic core values are hunting, not wildlife watching.

Julie: Yeah. The Northeast Washington Wildlife Group, that Commission Chair, Kim Thorburn is so interested in, they have proposed a management model adopted from Idaho’s model, which has to do with, instead of closing down hunting, when a specific number of cougars have been taken, Idaho starts restricting cougar harvest when the harvest has dropped below a certain number for two consecutive years. So it seems like these are things that the Washington Commission is potentially wanting to explore. I want to back up for a moment though. And when you were talking about California, we were saying that the higher, the allowance of cougars equals more conflict. Do you think that’s what’s happening in Northeast Washington? There are a lot of conflicts on that side of the State, and even some of the commission members were expressing puzzlement, not really knowing what that was about. And before we just go running to the conclusion of raising our harvesting numbers, let’s actually check in and see what’s going on there. But sadly sheriffs have resorted to taking matters into their own hands based on finding a loophole in the law, and have hired their own posse of trackers to hunt these cougars with hounds. Why are there so many conflicts with cougars in the Northeast part of the state?

Bob: So I do have those numbers in front of me. And I mentioned them earlier that up in District One, which is the three Northeast counties that only twice in the past decade has the cougar mortality total mortality been under 16%. And in the last two years, the 10-year average of cougars killed in the Northeast County has been a total of 53 cougars and 44 cougars by hunting. And the 16% guideline is 37 cougars. So they have been exceeding for eight of 10 years, the 37 cougars. And in the last two years, they’ve killed almost 150, 148 cougars.  About the same time that the sheriffs and special agents started running around killing cougars we’ve seen an increase in conflicts. We should also know however that there are several groups in Northeast Washington that have been putting up billboards and actively advertising that if you see at cougar, a wolf or a bear, call it in to the sheriff and then call WDFW.

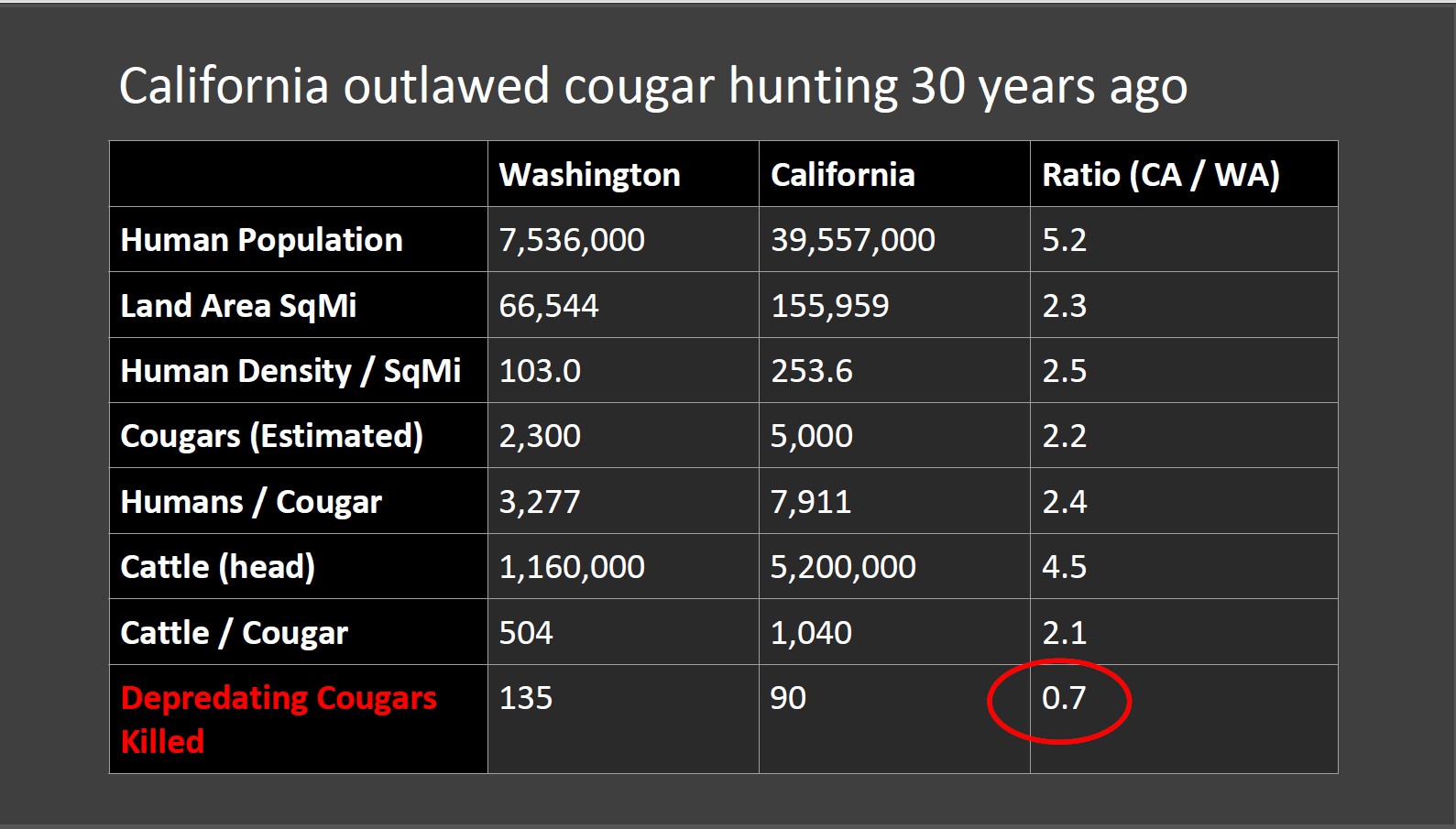

About the same time that the sheriffs and special agents started running around killing cougars we’ve seen an increase in conflicts. We should also know however that there are several groups in Northeast Washington that have been putting up billboards and actively advertising that if you see at cougar, a wolf or a bear, call it in to the sheriff and then call WDFW.  The correlative studies say that when you kill cougars, you have more troubles the next year. It looks to me like “there it is.” And then in a one-year snapshot, I did not too long ago, California has five times, five times the people that we have two and a half times as many cougars, four times as many cattle, and they had 70% of the cougar killed that we have here in Washington. So it appears we’re just creating our own problems. That’s what the science, scientists have been telling us since at least the 1970’s. So we ignore the science at our own risk.

The correlative studies say that when you kill cougars, you have more troubles the next year. It looks to me like “there it is.” And then in a one-year snapshot, I did not too long ago, California has five times, five times the people that we have two and a half times as many cougars, four times as many cattle, and they had 70% of the cougar killed that we have here in Washington. So it appears we’re just creating our own problems. That’s what the science, scientists have been telling us since at least the 1970’s. So we ignore the science at our own risk.

Julie: Well, that makes me wonder then, if there is a conflict with a cat and given the correlation between mortality and conflict, why aren’t the cats being relocated? What’s the rationale or the argument for or against that?

Bob: You’ve asked a really good question Julie. Cougars are territorial animals. The way it works is that female cougar gets to stay near mom’s home range. When a female kitten reaches independence and strikes out on her own, she might only move a few miles down the road, and if mom’s home range is such that there’s plenty of food available and all, she’ll be tolerated. A male kitten on the other hand has to get out of the area. The territorial tom, even if it’s his father, is going to be somewhat intolerant of having another male cat in its territory that would be competing not only for food, but for the right to procreate. So the young males tend to move, and in some cases, a thousand miles. If you had a conflict with a territorial male or a territorial female and you move them to a different area, you have multiple problems.

Bob: One is, is there already a territorial cat there who is not going to be very willing to, welcome someone new into the area? Relocating young males can probably be successful more so than, than older cats. I was fortunate to get to go along with a relocation of a young male. The biologists apparently knew of an area that seemed to be open and they put a collar on the, on the cat and released it. And the cat became successful and started taking deer and elk and with that was a successful relocation. So I think that can be done. Going back to the public safety issue, in 2010, the Department published a book, I think the title of it was a Cougar Outreach and Education, and they really have never bothered to help the public understand the nature of cougars, the probability of a cougar killing someone is really extremely low.

Bob: So what we need to do is to just to help people understand the nature of cougars and how to behave around them, how not to attract them, how to protect our livestock. So we really can coexist with cougars. They really seem to just be laid back, “Uh, let’s avoid conflict” type animals. The sheriffs don’t know the science, they’re feeling that “lead to the head” is an adequate way to protect people without thinking that well, you just opened up an area, another cougar is going to come in. Down in Goldendale a woman saw a cougar take down a deer. So the sheriff got his posse together apparently. They had to bring out a houndsman, finally located the cougar, chased it around a neighborhood shot at it six times before they finally killed this poor cat. And then in investigating found, it had also killed a doe and a faun and some raccoons and some possum. There was a cougar doing what cougars are supposed to do.

Julie: Yes.

Bob: In a rural farm area. And those farmers are complaining about elk and deer in their crops and raccoons. And it makes zero sense.

Julie: Can biologists accompany the sheriff, and his posse? I it seems like the Department of Fish and Wildlife should at least coordinate with the sheriff and say, look, if you’re going to do this, have a biologist go with you all because if it’s a young cougar, that way it can be relocated, or the biologists could determine, hey, it’s on a kill, it’s not, you know, it’s just doing what’s in its nature to do.

Bob: Well, the department has the ultimate authority. The sheriffs have declared themselves to be “Constitutional Sheriffs,” and they believe that somehow the US Constitution has given them ultimate authority in the county. But these are the same sheriffs who have said, they’re not going to enforce the new gun registration law that was voted overwhelmingly by the citizens of Washington State. So what the law says and what Fish and Wildlife says really doesn’t matter. And quite frankly, I don’t see Fish and Wildlife showing very much concern about the sheriffs killing predators, because it seems to kind of go along with their thoughts that “we need to kill more predators, because that’s what we do.”

Julie: That was my sense from listening to the minutes,

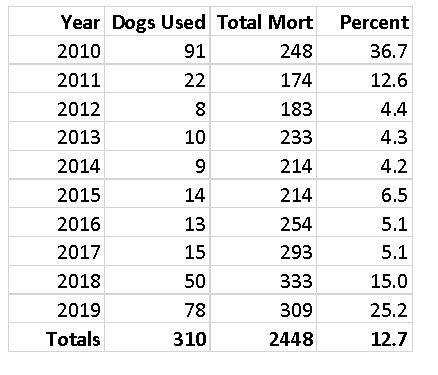

Bob: Do you know, we voted against hound hunting. And from 2012 to 2017 hounds were used 69 times. And then from 2018 to 2019, this is with the sheriff posses and all, they’ve been used 128 times. So in two years, we’ve killed cougars with hounds twice as many times. So pretty much the prohibition on hound hunting seems gone.

Julie: And listening to the minutes with the commission chair, Kim Thorburn seemed to be siding with the sheriffs. And I don’t, that’s just my, the way I heard it.

Bob: It’s a real problem Julie, in the big scheme of things, cougars contribute to our way of life that we have here in Washington of clean air, clean water, lots of opportunities to go out and see wildlife. They’re incredible animals. In this interview, we’ve talked about cougars as a kind of a population. The cougars are really individuals, just like we are, but all together, they’re just incredible cats, probably pound for pound, the strongest cat. Behind the cheetah, they’re the second fastest running cat, vertical leap of 12 to 15 feet, horizontally 35, 40 feet they’re just incredible animals.

Julie: You know, people love to observe these beautiful cats and they do so much good, as you’ve mentioned, for biodiversity and keeping balance in the ecosystem. Yet people, people fear them too and even vilify them, especially, you know, people living in or near these high density, cougar areas such as, Northeast Washington. So what can you say to those people who are really scared?

Bob: Fear, fear is a tough one. And the probably the best thing that we can say to them is this, come chat with us and let’s talk about cougars the animal and what are their habits? What are their behaviors? And if you live where you’re basically next to a territorial cougar, how do you deal with that? It’s doable. It’s done a lot in California. It’s done a lot here in Washington State. Education is really the key, Julie. Understanding how these cats fit into the ecosystem, how they work with us, Brian Kertson the state biologists found that people who live on the wildland-urban interface, where basically the forest starts turning into houses, in those areas, cougar spend 17% of their time on the urban side, on the housing side, they’re coming in and grabbing the deer that’s feeding on someone’s rose garden and dragging it under a bush in the greenbelt and eating it going and on about their business and generally unnoticed. Now everybody has these doorbells and trail cams all over so now we’re finding out, oh, there’s cougars out there. They have been in there a long time. You didn’t fear them, you didn’t know they were there. You needn’t fear them now. They’re still there.

Julie: Well, thank you for talking Bob. I really appreciate your taking the time to walk us through the issues.

Bob: Thank you for your time Julie, I really do appreciate it.

Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for non-commercial use for more information, visit mountainlion.org.

MORE ABOUT BOB MCCOY

Bob started researching Puma concolor and joined the Mountain Lion Foundation in 2009. The following year, he testified against the Washington Cougar Hounding Pilot Program, formed the Washington Cougar Coalition (WA Cougar), and became the Foundation’s Washington State Field Representative. Since then, he and volunteers have repeatedly stopped bills that would have harmed cougars. In 2013, Bob represented the Foundation on a panel at the 13th Mountain Lion Workshops in Utah. In 2015, Bob spurred WA Cougar to appeal the Washington Commission’s failure to follow proper procedure in setting cougar hunting guidelines. Led by HSUS lawyers, we achieved the first overturn of a citizen commission ruling by a governor in state history. The Commission returned in 2016 to the prior hunting quota. Bob is now working to keep the state from taking measures against cougars in retaliation for the successful return of wolves to Washington.

Bob started researching Puma concolor and joined the Mountain Lion Foundation in 2009. The following year, he testified against the Washington Cougar Hounding Pilot Program, formed the Washington Cougar Coalition (WA Cougar), and became the Foundation’s Washington State Field Representative. Since then, he and volunteers have repeatedly stopped bills that would have harmed cougars. In 2013, Bob represented the Foundation on a panel at the 13th Mountain Lion Workshops in Utah. In 2015, Bob spurred WA Cougar to appeal the Washington Commission’s failure to follow proper procedure in setting cougar hunting guidelines. Led by HSUS lawyers, we achieved the first overturn of a citizen commission ruling by a governor in state history. The Commission returned in 2016 to the prior hunting quota. Bob is now working to keep the state from taking measures against cougars in retaliation for the successful return of wolves to Washington.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email