Defining Depredation in California

By Mountain Lion Foundation Staff

Mountain Lion Foundation created an interactive overview on what happens when mountain lions prey on pets or livestock in California. It’s always sad when this happens, devastating for the owner, often lethal for the lion, and is usually an avoidable situation. See the story map here

I. Definition

Historically, the word “depredation” has been used in the context of a military raid or pillaging a village. In the dictionary, it is defined as:

- the act of preying upon or plundering; robbery; ravage

- A predatory attack; a raid.

- Damage or loss; ravage

Wildlife management agencies primarily use the word depredation for instances where a wild predator attacks or preys upon a domestic animal, such as a family pet or livestock. In places where it is legal to retaliate for this “damage or loss” by having the nuisance wild animal killed, a Depredation Permit is issued to the pet/livestock owner.

Coincidentally, the word is the combination of the prefix “de” meaning removal or reversal, and the root “predation,” for a wild animal hunting prey. Because of this, the term “de-predation” is also sometimes used to describe the depredation permit in terms of it being the removal of a predator.

So, the initial predatory attack and the resulting permit for killing the lion both use the word depredation, even though a slightly different definition may be implied. Either way, if a mountain lion damages a person’s property in California, a permit must be issued to have the lion killed if one is requested (see California Fish and Game Code Section 4803).

II. History

Ranching began in North America during the 16th century when early explorers and settlers first brought over livestock from Europe. Over four-hundred years later, the ranching industry has become a cornerstone of American culture. During WWI, increasing cattle production to support the troops was seen as a patriotic duty. Wild animals were either viewed as competition (deer, elk, bison, etc.) for grazing resources, or as a liability (wolves, cougars, prairie dogs, beavers, etc.) because of predation or causing damage to ranching land. Thus, wildlife was a problem and viewed as something that needed to be controlled and eliminated.

Though we now know better, many of the beliefs from a century ago still exist today:

- the government should remove nuisance wildlife

- it is acceptable or even encouraged to kill wild animals on one’s land

- wild animals belong out in the woods, away from people

- wildlife should “know better” than to come onto our land; killing them will instill fear of man

Mountain lions are territorial and when one is killed, multiple younger lions may move in to fill the space. Younger cats are more likely to be tempted by domestic animals and may continue the cycle of livestock losses and having lions killed. Shooting a lion does not undo the death of a domestic animal, does not prevent future livestock losses, and costs tax payer money.

Florida is the only state that will not issue depredation permits for lions (referred to locally as panthers) that threaten or have killed domestic animals. Residents are allowed to scare a panther away if it is on their property or stalking a pet, but they may not injure or kill it. This policy is due to panthers being federally listed as a critically endangered species with less than two-hundred left in the wild. Every single panther is essential for the recovery of the species.

Because they do not have the luxury of a depredation permit, Florida residents are aware they must take preventative measures. No other state values their lions enough to enact similar policies and require its citizens to be proactive.

Because they do not have the luxury of a depredation permit, Florida residents are aware they must take preventative measures. No other state values their lions enough to enact similar policies and require its citizens to be proactive.

In most situations, there is no limit to the number of depredation permits a person may be issued, nor are there prerequisites for animal husbandry (such as not tying a goat to a fencepost over night), and no required education or assistance after the incident to help the owner prevent future losses.

In California there are two notable exceptions, the Santa Ana Mountains and the Santa Monica Mountains. In each of these areas, CDFW recognizes that the mountain lion population has become too imperiled, and individuals too important, to manage depredations without restrictions. In these areas, landowners who lose animals to mountain lions are given additional help to prevent future losses rather than lethal removal permits at the onset.

III. Prevention

While killing a lion for depredation is historically common and culturally acceptable, it is not a productive solution and is an unnecessary loss of life. MLF has created a variety of information and tips for keeping domestic animals safe and coexisting with wildlife. These resources for non-lethal animal husbandry techniques are available and explained more thoroughly in the Protecting People, Pets and Livestock section of this website.

Click on any of the bullet points for more information.

IV.Getting a Depredation Permit in California

A. Sighting or Public Safety (No Depredation Permit)

If a mountain lion is seen on one’s property, or evidence of a lion is found such as scat, tracks, or a deer kill, a phone call to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife may result in an officer coming out to investigate, or they may simply record your sighting over the phone. Because there has been no damage or immediate danger, a depredation permit is not issued. Seeing a lion is not legal cause to kill it. If the lion has not threatened any people, pets, or livestock, usually it is left alone to move on naturally.

However, if an officer (CDFW or local law enforcement) responds and the lion is present, the situation may be classified as a Potential Human Conflict: A mountain lion that is found in an unusual location and/or is demonstrating unusual behavior that could reasonably be perceived as having potential to cause severe injury or death to humans (a possible situation that may exist before a lion becomes an actual public safety threat).

However, if an officer (CDFW or local law enforcement) responds and the lion is present, the situation may be classified as a Potential Human Conflict: A mountain lion that is found in an unusual location and/or is demonstrating unusual behavior that could reasonably be perceived as having potential to cause severe injury or death to humans (a possible situation that may exist before a lion becomes an actual public safety threat).

Under a n ew law (§4801.5) that went into effect January 1, 2014 only a mountain lion posing an imminent threat to human life may be killed for public safety. This is defined by the lion exhibiting one or more aggressive behaviors directed toward a person that is not reasonably believed to be due to the presence of responders. All situations that do not meet this threshold must be resolved with non-lethal force (hazing, tranquilizing, capturing, relocating, monitoring, etc.).

ew law (§4801.5) that went into effect January 1, 2014 only a mountain lion posing an imminent threat to human life may be killed for public safety. This is defined by the lion exhibiting one or more aggressive behaviors directed toward a person that is not reasonably believed to be due to the presence of responders. All situations that do not meet this threshold must be resolved with non-lethal force (hazing, tranquilizing, capturing, relocating, monitoring, etc.).

B. Caught in the Act

If a mountain lion is found in the act of attacking a domestic animal or is seen as an immediate threat to human life, it may be killed by a resident, without repercussion, as long as the California Department of Fish and Wildlife is immediately notified after the incident. CDFW will confirm it was the only option to prevent loss of life to people or property (pets or livestock being the property). A verbal depredation permit can be issued over the phone and followed up later with the necessary documentation.

It is highly recommended to contact CDFW first, before any action is taken against the lion. If the Department finds there was no immediate danger, a shooter can be prosecuted for poaching since mountain lions are a specially protected mammal in California. The local police department and/or county sheriffs office can also respond to mountain lion-public safety calls to a 911 operator.

C. After a Loss — Depredation Permit Process

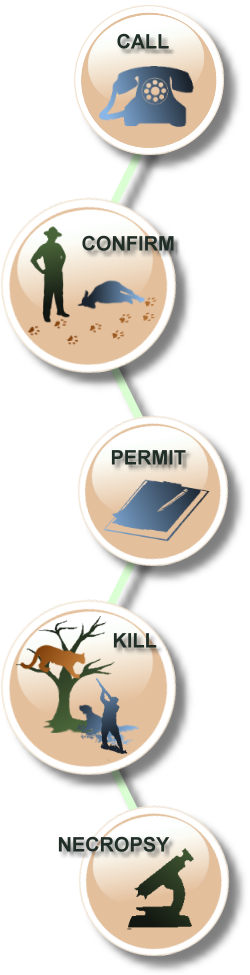

If a domestic animal (pet/livestock) is injured or killed by a mountain lion, the owner has the legal right in California to have the mountain lion killed. The following steps give an overview of the process.

- Call the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s regional office, or visit their Wildlife Incident Reporting website. They will put you in touch with a local biologist or warden.

- The responding officer will visit the property to determine if a lion is responsible for the killing of a pet or livestock.

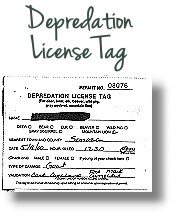

- The officer will fill out a Wildlife Incident Report. If a lion is responsible, he or she will then issue the homeowner a Depredation Permit, and contact the local USDA Wildlife Services’ county trapper to come out to track and kill the lion. The Depredation Permit:

- expires 10 days after issuance

- may only be carried out by the permit recipient, employee of the owner of the damaged or destroyed property, any county or city predator control officer, any employee of the Animal Damage Control Section of the United States Department of Agriculture, any departmental personnel, or any authorized or permitted houndsman registered with the department as possessing the requisite experience and having no prior conviction of any provision of the Fish and Game Code or regulation adopted pursuant to the Code

- authorizes the holder to begin pursuit not more than one mile from the depredation site, and limits the pursuit of the depredating mountain lion to within a 10-mile radius from the location of the reported damage or destruction

- prohibits any lion from being captured or killed with the use of poison, leg-hold or metal-jawed traps, and snares

- requires the capturing, injuring or killing of a mountain lion be reported back to CDFW within 24 hours

- requires any killed mountain lion be turned over to CDFW, a Depredation License Tag filled out, and the department to perform a complete necropsy on the carcass

- The Wildlife Services trapper may also fill out a Reportable Animal Action Report. The carcass of any killed lion must be turned over to CDFW for a full necropsy (animal autopsy).

Depredation Permits expire after ten days because lions roam such large territories. A lion seen in the area after that time may not be the same one that caused the damage. Many biologists believe younger, dispersing lions are more likely to cause depredation, and these cats will often travel hundreds of miles to find a home range. A juvenile dispersing lion may only stay in one area for a few days. Adult resident lions will usually keep the younger ones out. Killing a non-depredating adult lion is not a good idea, as this opens his territory for several younger lions to move in and may ultimately increase conflicts.

Mountain lions have been a specially protected mammal in California since the passage of Proposition 117 in 1990. Under the law (California Fish and Game Code, Section 4800), even deceased lions or any part of a mountain lion may not be possessed (unless the owner can demonstrate that the mountain lion, or part or product thereof, has been in the person’s possession since June 6, 1990). All mountain lions killed for depredation must be turned over to CDFW. By law (§4807(b)), the Department is required to conduct a complete necropsy on each carcass. The findings from these examinations are made public through an annual report submitted by the California Fish and Game Commission to the Legislature.

In 2011, the Mountain Lion Foundation worked with Senator Fuller and Assembly Member Huffman to pass legislation (Senate Bill 769) to allow educational facilities to obtain permits to acquire and display deceased mountain lions. Though no longer able to fulfill their important role on the landscape, dead lions can help us to better understand and protect the species. To learn more about obtaining a lion carcass, visit Mountain Lion Educational Displays in California.

D. Limits on Depredation Activities

On December 15, 2017, California Department of Fish and Wildlife issued an amendment to the Mountain Lion Depredation, Public Safety, and Animal Welfare Policy that now allows CDFW to tailor their response to the specific circumstances of a depredation incident, providing a wider variety of management tools and greater protection for livestock, people and mountain lions.

As a result of these efforts the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s has amended their Policy to provide additional protection to endangered mountain lion populations in the Santa Ana and Santa Monica mountains.

A three-tier stepwise process in these areas has been adopted:

First Depredation Event

- CDFW must confirm depredation as that by a mountain lion.

- Non-lethal depredation permit to pursue/haze the depredating mountain lion shall be issued. It shall explicitly indicate that no mountain lion shall be intentionally killed during pursuit.

- Education by CDFW regarding mountain lion behavior, carcass removal, proper fencing and/or enclosures for livestock, brush clearing, and how to remove lion attractants from property.

Second Depredation Event

- CDFW must confirm depredation as that by a mountain lion AND responding party must show that all reasonable preventative measures recommended by CDFW at time of first depredation event were met.

- Existing non-lethal depredation permit to pursue/haze the depredating mountain lion shall be amended, or new non-lethal permit shall be issued. It shall explicitly indicate that no mountain lion shall be intentionally killed during pursuit.

Third Depredation Event

- CDFW must confirm depredation as that by a mountain lion AND responding party must show that all reasonable preventative measures required in the existing permit(s) were implemented AND responding party requests a lethal permit, the Department shall issue a depredation permit to lethally remove the depredating mountain lion

V. Depredation Records

Almost all state game agencies keep track of the number of mountain lions killed annually for depredation. Some states even go as far as recording the breed of domestic animal lost and if preventative measures were implemented. The Mountain Lion Foundation requests copies of these reports and keeps track of mountain lions killed in each state.

Residents who do not wish to have an offending lion killed do not have to report pet/livestock depredation losses to their state game agency. In addition to the number of lions killed under depredation permits in each county, California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife also keeps track of the number of depredation permits it issues.

In California, the Department of Fish and Wildlife is the agency responsible for issuing depredation permits, keeping track of the number of lions killed, and conducting a necropsy on each carcass. However, because the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s Wildlife Services branch is the agency that hires the county trappers who actually hunt and kill depredating mountain lions, they also document incident reports and lions killed.

The USDA’s parent agency, APHIS, maintains detailed records of all wildlife damage reports and the inventory of kills. On their website, APHIS lists reports from 1996 through 2014 according to fiscal year.

California Mountain Lion Depredation

| Year | Depredation Permits Issued |

Lions Killed (CDFW Records) |

Lions Killed (WS Records) |

Necropsies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 208 | 105 | 110 | N/A |

| 2004 | 256 | 120 | 133 | N/A |

| 2005 | 209 | 116 | 120 | 14 |

| 2006 | 169 | 87 | 115 | 28 |

| 2007 | 238 | 150 | 137 | 42 |

| 2008 | 144 | 60 | 123 | 16 |

| 2009 | 135 | 70 | 103 | 9 |

| 2010 | 132 | 59 | 108 | 13 |

| 2011 | 137 | 76 | 104 | 15 |

| 2012 | 137 | 62 | 77 | 7 |

| 2013 | 148 | 62 | 28 | 59 |

| 2014 | 216 | 89 | 78 | 51 |

| 2015 | 256 | 107 | N/A | 83 |

| TOTAL | 2,385 | 1,163 | 1,236 | 337 |

The provision to conduct a necropsy on every mountain lion carcass turned in is intended to provide CDFW and the legislature with critical information needed to properly ascertain the health and sustainability of California’s mountain lion population, and to determine whether or not the depredation permit system is being abused.

Based on a 2013 report by CDFW, only 25 percent of the mountain lions examined from 2006 to 2012 contained the remains of pets or livestock in their stomachs. If this percentage is extrapolated, then hundreds of lions have died needlessly. We must ensure that proper measures are in place to definitively identify offending mountain lions.

The Mountain Lion Foundation is looking into reforming the depredation process both in California and other states where lions are needlessly being killed. To stay up to date on our projects and to join us in this fight, please become a member today!

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email