One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

An Audio Interview with Julie West, MLF Broadcaster

Listen Now!

Listen Now!

Listen to the interview from MLF’s ON AIR program, podcasting research and policy discussions about the issues that face the American lion.

Transcript of Interview

Intro: (music) Welcome to On Air with the Mountain Lion Foundation, broadcasting research and policy discussions to understand the issues that face the American lion.

Julie: Hello. You are listening to On Air with the Mountain Lion Foundation. I’m Julie West, your host. My guest today is Phil Carter, wildlife campaign manager with Animal Protection of New Mexico, a non-profit organization that has been advocating the rights of animals since 1979. APNM tirelessly works to reverse the outmoded view that cougars are nuisance animals that should be eradicated, and it aims to counter these prejudices with a biocentric approach accomplished through education, outreach, and campaigns for the protection of and coexistence with wild species in New Mexico.

Phil coordinates campaigns on behalf of the organization and initiates collaboration with state officials and the general public to produce progressive change in New Mexico cougar management. To this end, he networks and communicates with land owners, other non-profit organizations, New Mexico department of Game and Fish, New Mexico Environment Department, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, New Mexico State Parks, tribes, and other agencies about human/animal conflicts and benefits.

So, welcome Phil. Hello.

Phil: Thanks for having me on.

Julie: Yes. Now, I understand that New Mexico is considered to be a premier site for cougar populations. What are the variables that make it so, and what significance does this hold for their survival?

Phil: Well, New Mexico certainly has a fairly robust population of mountain lions. They were never really hunted out here in this state. There’s always been kind of a background population. Again, the mountain terrain, relatively low population of the state — there’s only about 2 million New Mexicans — means there’s a lot of open space where these cougars can live and thrive.

Julie: What are the issues at stake for the cougar in New Mexico?

Phil: Certainly my organization, Animal Protection of New Mexico, has been working with the state wildlife agency, which is the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, for coming up on 15 years now, really kind of working with them to manage these cougars better, more scientifically.

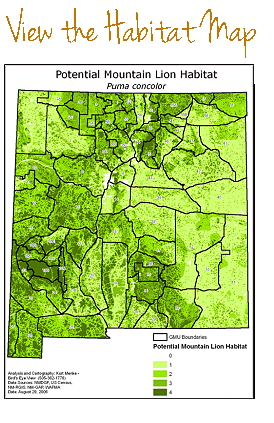

We had a lot of really progressive changes in management in the last decade, around 2005-2006, which included development of a really thorough, complex habitat map, which is something the department never had, that in coordination with our organization we were able to produce something to really better manage the cougar population in each, what they call, game management unit around the state, of which there are dozens.

Also a change that we helped Game and Fish work on in cougar management was the institution of what’s called the Total Sustainable Mortality Limits for Cougar Management. What this does is it monitors total mortality of cougars, not just from harvest, which cougars are legal to hunt here in New Mexico, but also any sort of deaths of cougars from road kills, depredation, or other natural causes.

It really gives a much more clear picture about how many cougars, of this small population here in New Mexico, are dying off and when do game management units need to be closed or when does hunting need to be limited to make sure we have a robust and sustainable population of the cats.

Julie: What are the numbers that reflect that total sustainable mortality rate?

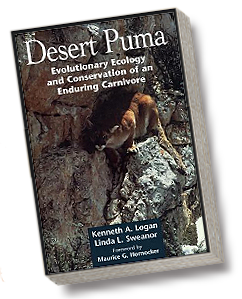

Phil: Basically New Mexico is the site of an extremely thorough study called – it was published as Desert Puma, by Dr. Logan and Dr. Sweanor, Ken Logan and Dr. Sweanor, who both work for Colorado Fish and Wildlife Department.

The numbers that they came up with from that 10 year study, that was paid for by New Mexico tax payers to the tune of about a million dollars, the conservative estimates of the total populations of cougars are around 2041 to 3043. So between 2000 and 3000 here in New Mexico.

Again, this is really just a premier cougar population study. I don’t know if anything that is more thorough that’s been done in any other state.

Julie: Your organization uses the Hornocker study.

Phil: Yes, definitely. It’s the opinion of a lot of us in the environmental community that ever since the Hornocker study was published around 2000-2001, the Game and Fish Department here in New Mexico have been giving a concerted effort to downplay it’s finding, which is disappointing as it was a taxpayer funded study, and it is such a great resource for wildlife managers here.

Julie: So the Hornocker study suggested that the population numbers were hovering right around 3000-3043, and what do the total sustainable mortality figures reflect in relation to that number?

Phil: It varies by game management units here in New Mexico. I don’t know of any game management unit under the more conservative estimates by the Hornocker study that are over 400 cougars. Again, that’s on the high end, and I should really just back up and say it’s really just 2000 to 3000 are the conservative estimates of the total population here in New Mexico.

Now, asking the Game and Fish Department, their biologists starting in 2010, they went to the extreme high end of what the Hornocker study prescribed and decided that they were going to consider total cougar population here in the state as between 3000 and 4200. That was the first indication that my organization and others was that something’s not quite right about such a drastic change in management in just one year.

Julie: How did those numbers, then, influence the hunting quotas on cougars?

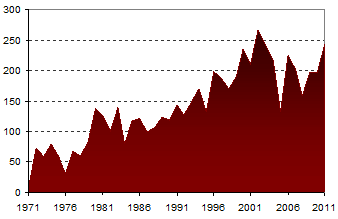

Phil: In July, 2010, the Game and Fish Department issued its recommendations for the next round of what’s called the Bear and Cougar Rule here in New Mexico. This is what dictates management of both black bears and mountain lions here.

Where it was an annual quota, which is basically the hunting quota, how many cougars can be sustainably managed and hunted per year, where it was in 2009 at 490 cougars per year, it got bumped up, just in the span of one year, to 1109. Those were the new recommendations issued in July 2010 by Game and Fish Department. There was also a huge increase of the female sub-limits, which is basically the quota for hunting female cougars. Where it was 126, it became 386.

Julie: Right. That was approximately a 200 percent increase in their sub-quota. Considering females are considered to be the biological bank account, so to speak, of the population, they should require special care. Is it reasonable to suggest that these quotas could potentially eradicate the population?

Phil: Certainly, me and my colleagues in the environmental community made those suggestions heavily when those recommendations were released in July 2010. Through our efforts at working with state government, including the governor’s office, as well as mobilizing the public who was concerned about such a drastic increase, Game and Fish Department came back in late August, 2010, with a new number that shows 996 cougars per year.

Julie: So it had been 409. They proposed over 1110…

Phil: 490.

Julie: … and then there was a public outcry to reduce that number to whatever you said – 900 and some? And what is the current quota in 2012?

Phil: The current quota, because that new number, 996, didn’t satisfy me and my colleagues in the environmental community either. The reason for that being is a number of reasons was the Game and Fish Department was using, in our opinion, was essentially replacing the Hornocker Study with what was called the Perry Study. What this was a one-year study that was conducted as a Masters thesis here in New Mexico. A population survey on one small area.

At the time the Game and Fish Department was citing it as the main source of their population assumption for cougars in New Mexico, it had not been published, nor had it even been peer reviewed. It was only submitted as a Masters thesis. That kind of really set off some red flags amongst me and my colleagues.

So we filed what was basically the state version of a freedom of information act request here in New Mexico, which all three agencies are required to comply with within 2 weeks. One of our requests was can we see a copy of this Perry study, because as it wasn’t published or even mentioned in any scientific journal, we couldn’t get a copy of it.

Two weeks later, I get contacted by Game and Fish to come pick up the documents, and lo and behold, the Game and Fish Department office claimed they didn’t even have a copy of the study. What they were essentially using as a major basis of the population assumptions for cougars, they claimed to not even have a copy of it within their office.

Julie: How does something like that get through the cracks? You would think that they would be working very closely with wildlife biologists to get the latest numbers in order to better reflect policy. How did something like that happen? What was the reasoning?

Phil: Unfortunately, New Mexico state law is not like federal law. For the endangered species act, you’re required to use what’s called best available science. New Mexico has no such provision like that. So really the wildlife biologists in the employment of the state are kind of free to set their own determination to the best available science.

Ultimately they decided to largely base their population figures on what we considered a highly questionable study, which is not to downplay the value of the study itself. We later had to get a copy of it from Dr. Perry himself, because the state didn’t have a copy of it. But to base something as important as cougar population figures on a one-year study that had not received any peer review, nor was even published, we considered highly questionable.

Julie: So if wildlife biologists themselves were in a sense advocating for this document, using it as their baseline, it sounds like there must be some division within the wildlife biology community itself. Do the biologists sit down, convene at a table with everybody and hash these discrepancies out? Was there any kind of a meeting to really look closely at these figures?

Phil: I assume that the department biologists had met amongst themselves and decided to use this particular study, as well as a few others, to make these determinations. But certainly my organization, nor any of my fellow environmental organizations were not invited to the table that time.

For the endangered species act, you’re required to use what’s called best available science. New Mexico has no such provision like that.

Julie: So it’s encouraging then that the public actually lobbied on behalf of the mountain lion and in essence were responsible for the lowering of that initial number. What do you account for the public’s support of the mountain lion in New Mexico?

Phil: I think organizing on our part with APNM and other organizations and the fact that it was a kind of a shock to a lot of people to have essentially a 200 percent increase originally, I think really galvanized a lot of public opposition.

Julie: Especially if you were to take the high end. Even if you were to take the 4200 end of the Hornocker Study, or 3000, that 1000 figure is outrageous.

Phil: Right. It’s essentially they were claiming a quarter more cougars than what we considered under the precautionary principal that this has always been a relatively rare species and management really needs to reflect that. And then as you mentioned, ultimately in October, 2010, at the final vote the Game and Fish Department lowered the total quota further to about 742 cougars total. But there’s this kind of this pervasive sense of arbitrariness to all these numbers because really even under the original 490 number, hunters rarely got over 200 cougars per year. The fact was trying so outrageous increases on this when, even under the original quota, hunters were getting less than half of it per year, was really almost kind of surreal to watch play out like that.

Julie: So there’s an inflation between the actual harvest quota and the total projected quota.

Phil: Right. It’s very strange to watch play out because the Game and Fish biologists, as well as the Game commissioners are very aware that only a percentage of these hunting quotas are being met from year to year.

Julie: Then maybe can that suggest, potentially, a lower population than originally thought if consistently hunters can’t even bring in more than 200 a year? Does that mean that the population is perhaps more fragile than we think?

Phil: You can certainly make that argument. There was a number of new developments in cougar management this past spring certainly. In issuing them, Game and Fish Department has stuck to its guns in claiming that what we consider drastic change in cougar management, are necessary because, in their quote, “There are too many mountain lions.” Whether that’s the truth, I don’t think has ever really been adequately proven by them or anyone else.

Julie: And studies show that high hunting pressures actually can destabilize a cougar population and contribute to more incidents and issues. Gary Kohler is a wildlife biologist living in Washington, who I interviewed previously with The Mountain Lion Foundation, who speaks about when you remove the elders from the population, you essentially have these young and really juveniles on your hands, who are really trying to disperse and to take over new territory. By coming in and over hunting, you are upsetting a balance that the animals themselves have helped to create.

Phil: Yes. In the 2012 recommendations by Game and Fish Departments, there was a section that we found particularly egregious that essentially the agency said that it relied on Drs. Logan and Sweanor’s research to conclude that exploitation of a cougar population would increase public safety, and that is just not supported in the scientific literature, whatsoever.

Julie: So you referenced the 2010 modifications that the Mexico Department of Game and Fish proposed. Where are we now in 2012? What’s happened?

Phil: This past spring, the Game and Fish Department issued some new amendments to the bear and cougar rule, that were kind of slipped in under the radar that we definitely felt like there were some really drastic changes to cougar management contained in these amendments.

The biggest one is, like I mentioned earlier in the podcast, we helped Game and Fish Department institute a new management paradigm called the Total Sustainable Mortality, which accounts of all cougar deaths within a game management unit, not just hunting.

Well, that was pretty much thrown aside during the 2012 amendments and now cougar harvest which is total cougars killed through hunting is the only thing that’s going to determine game management zone closures from now on.

Julie: So that means if a cougar gets hit on the highway or succumbs to natural death, all of those kind of deaths are not counted?

Phil: That’s correct. They’re no longer counted. They’re counted, but they do not effect any sort of management changes, only hunting is going to determine what game and management zones are closed. It’s essentially working at a deficit of cougars due in the fact that you’re not responding to other forms of mortality to these cougars.

Julie: Development and road death, I would think, would account for a high percentage of cougar deaths.

Phil: Yes. It’s probably around 80 to 90 percent, I believe is what the department has claimed is the cause of mortality is hunting, so that hunting accounts for about 80 to 90 percent of mortalities is what the department claims. I’m not sure about that, but it really defies any sort of precautionary principle as far as managing a pretty rare species to not include these other forms of mortality like road kill or natural depredation.

Another really big change that occurred this past spring was, where the cougar hunting season was limited from October to March, it is now a year-round enterprise. You can go out and hunt cougars at anytime during the year. Also the bag limits for these hunters has doubled. Where you could only take one cougar per hunting per trip, now you can take two.

Julie: So what about mating season and when mothers have their children? That there’s just disregard for those seasonal changes?

Phil: That’s what it appears like, that the Game and Fish Department is now completely disregarding cougar biology and mating, as far as its overall scientific management of the species goes.

Julie: Who’s tracking those changes, just to see what kind of difference this is already making on habitat?

Phil:These new amendments haven’t been in place very long. They were voted in unanimously by the State Game Commission in June at their meeting. It remains to be seen what the effects on these populations is going to be. The wildlife biologists employed by the State are responsible for maintaining these studies of how it’s effecting cougar populations.

Julie: When the department makes it known that they are going to be considering modification of policy, do you see all kinds of interest groups, I would imagine, lobbying to be heard from biologist themselves to hunters to individuals such as yourself and the public, there are opportunities to come present your information for consideration, at some point. How good are they at making those opportunities available and known?

Phil: The amendments are published on the Game and Fish Department’s website and are open to a public comment period, so the State Game Commission holds one public comment period at some location within the state, at one meeting and then at the next meeting they vote yea or nay on changes in management on this. Both the environmental groups, as well as other groups like the hunting interest groups, are out there, generally at odds, although not always. It’s always an issue as far as who’s going to be heard, who’s gets their membership out better.

I would say that I think we have a game commission that’s much more stacked to the agricultural interests and hunter interests, than we have had in years past. The State Game Commission is a body that’s appointed by the Governor’s office. It’s been traditional to have at least one commissioner from the environmental communities sitting on that, but we haven’t really had that at all since 2010, which is quite disappointing when you look at the over-all percentages of what people use their public lands here in New Mexico for. The people who get out for hiking and especially wildlife watching, which has it’s own designation, far, far outstrip by many orders of magnitude the people who are out for hunting or angling or trapping. If this game commission was truly representative of what the public is using it’s public lands for, and public’s wildlife for, they should have a mostly environmentalist panel makeup, but they very much do not.

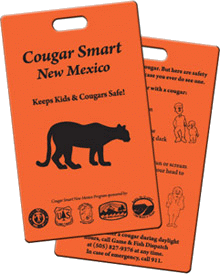

Julie: Let’s back up a minute because you were talking about the public outcry, and I know that one component of what Animal Protection of New Mexico does is something called “Cougar Smart New Mexico.” It’s an outreach program you’ve developed in collaboration with the Santa Fe County Open Space and Trails, but also some of the entities mentioned in our introduction, the New Mexico State Parks, and so on. Tell me about this outreach program and what are some of the kind of things it undertakes?

Phil: Because public safety is often used as a rational for managing or even over-managing of cougars to the point of expiration, we developed this program called “Cougar Smart” which has a number of materials which is distributed for free. We also give outreach talks, especially to families and children all over the state.

What it is, is basically information on safe and responsible conduct within cougar country. Just really tidbits about if you see a cougar, what’s the safe course of action: don’t run, look big, certainly don’t play dead, make a lot of noise. And also other really helpful tips like: always keep your dog leashed when out in cougar country, including national forest lands, walk in groups, make sure children stay near adults, things like that just to make sure that people stay safe and we don’t have – while attacks are extremely rare, they do happen. We had 2 fairly high-profile cougar attacks back in 2008. So just to be proactive in making sure people stay safe so these animals aren’t persecuted on behalf of a misguided approach toward public safety.

Julie: Are there any guidelines available for ranchers or those with livestock?

Phil: We don’t publish those. A number of other group do, including I believe Defenders of Wildlife does. I want to say The Mountain Lion Foundation has also produced materials on that, though, I could be wrong.

The total number of livestock loss from native carnivores, including mountain lions, but also wolves and coyotes, is extremely small. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s own figures show that. So we’re always trying to downplay the actual danger to both humans and livestock from these animals when far more head of livestock are lost to exposure, dehydration, even lightning strikes per year.

Julie: And cougars and other large predators can actually benefit prey populations, can’t they?

Phil: Absolutely. Definitely keeping deer and elk, and other ungulate populations in check, culling of the weak and through the trophic systems of biology, keeping deer and other populations in check benefits other animals including beaver, foxes, rodents, all sorts of creatures. Mountain lions really do have a very vital place within the ecosystem. So it’s disappointing to see when wildlife management seems to think they are an inexhaustible resource.

Julie: What’s the state of cougar research like today? Is there a healthy number of potential next generation of cougar biologists who are interested in working with your organization, who are helping to keep the figures current, the data current?

Phil: Right. We are always looking to collaborate with people who are really interested in working on cougar biology and all that. I don’t foresee it, as we’re kind of in a different political climate than we were back in the mid to late 90s when this Hornocker study was done with taxpayer money. I don’t see something like that happening again, but we’ll definitely coordinate with a number of biologists, and always welcome really good hard data on just what the mountain lion populations is and what the state of their wellbeing is.

Julie: And what do the habitat maps reveal now? Where are the healthy populations located in the state?

Julie: And what do the habitat maps reveal now? Where are the healthy populations located in the state?Phil: They’re all over. New Mexico has kind of a band of the Rocky Mountains going down through the central part of it, and so that’s where we’re seeing a lot of the populations, although there are more isolated clusters as well in the southeast and northwest sections of the state as well.

Julie: Tell me what some of the current projects are on the table for you and your peers.

Phil: We’re continuing to get the word out about the “Cougar Smart” program to school groups. I’ve had a lot of interaction over the past year with groups like the Valles Caldera National Preserve. They had their annual marathon back in June. Every year they have an animal theme for it, and this year it was year of the cougar. It was really fun to coordinate with the Valles Caldera National Preserve on getting information out, as well as distributing the “Cougar Smart” materials

We also had a lot of good interaction with the State Girl Scout Association here. It’s been great working with them. They have a number of really interesting badges, projects that their scouts do related to wildlife management. So, it’s been really fun working with some of the young, what I would consider potential activists, certainly. Young kids really looking to learn more about the issue.

Julie: Absolutely.

Phil: We’ve recently manufactured some metal versions of our “Cougar Smart” informational signs for the state park system, getting that out to a number of locations around the state, which has been a great development, too. And, we’ve been talking with the Forest Service for a couple of years now about possibly adapting this “Cougar Smart” program to the national campaign, similar to their “Be Bear Aware” program.

Julie: Nice. Are there other advocacy groups in other states that your group partners with or looks to as a role model, for example, on how to implement new strategies?

Phil: Oh yeah, certainly. Mountain Lion Foundation has always been quite supportive as have the Cougar Fund. We continue to work with the Hornocker Institute, as well as the biologist, Sharon Negri, on just about getting responsible management to cougars, not just in New Mexico, but across the west.

Julie: Can you conclude with a cougar story of your own? Have you ever seen a cougar in the wild?

Phil: No. I never have, personally. It’s kind of an ongoing dream. My parents live up in southern Colorado, in the San Luis Valley, and they saw a mountain lion probably about 500 yards from their house recently, so I was really jealous for that. I’ve definitely heard them when I’ve been out camping, but as of yet, I’ve not seen them. It’s kind of an on going hope that I will someday.

Julie: They’re elusive creatures, aren’t they?

Phil: Very.

Julie: Well, Phil Carter, a pleasure to speak with you. Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us today.

Phil: Great. I really appreciate it. Thanks very much.

Julie: And good luck with your next wave of projects.

You’ve been listening to Phil Carter, wildlife campaign manager with Animal Protection of New Mexico. I’m Julie West with the Mountain Lion Foundation. Thank you.

Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for noncommercial use. For more information visit mountainlion.org.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email