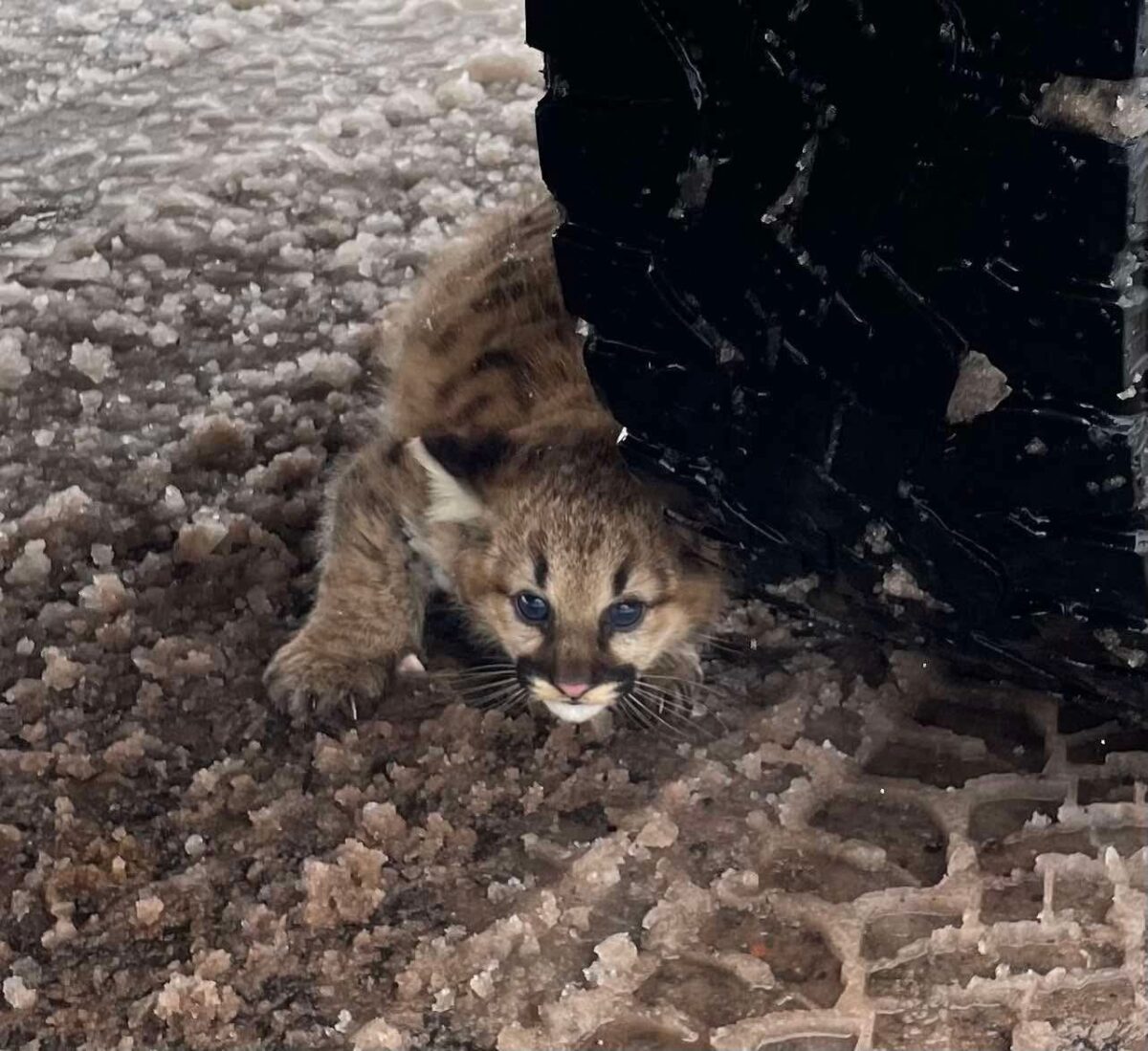

At the end of August, a young mountain lion was killed after attacking a child in a yard near Calabasas, CA. The child’s mother responded well, quickly driving away the mountain lion and bringing in police and officers from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, who tracked and killed the cub.

In a horrific and tragic situation, mixed with our grief for the injured child and the community’s fear, we’re grateful that events resolved almost as well as they could have. The child is reportedly recovering well. After finding and killing the attacking lion, officers continued searching and located its mother and a sibling. Thanks to the careful and responsible approach of law enforcement, those mountain lions were captured unharmed. When no evidence was found that they had harmed a person, they were set free at a location farther from people.

This is the first mountain lion attack on person in Los Angeles County since 1995. With an endangered population of around 5-10 mountain lions in the Santa Monica Mountains, there’s no doubt that they often come close to people. Each moves through a territory of 50 square miles, usually without anyone knowing they were in the presence of this wide-ranging and secretive neighbor. The lion killed in this case was young, still learning how to behave, and suffered the ultimate consequence for its unfortunate choice. Its sibling and mother had already learned to avoid people, and thanks to the careful work by state and federal wildlife officials, they are free to continue living as mountain lions should.

As more Californians move closer to nature, people and cougars will cross paths more often. Mountain lions have always been in our yards, but doorbell cameras, security systems, and trail cameras are revealing how often mountain lions cruise through our neighborhoods. Discovering our mountain lion neighbors shouldn’t be cause for fear. Their presence is a reminder that our homes are built where mountain lions and their kin have roamed for millions of years, and one sign of the health of the wilderness we see out our windows.

After centuries of treating carnivores as enemies to be killed on sight — the policy and attitude that left our state bereft of the bears that grace our flag — wild places are recovering. While some mountain lion populations are under consideration for state endangered species listing, other populations in the state are recovering from the indiscriminate slaughter of an earlier era. Maintaining healthy populations of mountain lions benefits us all. Healthy forests need carnivores, and healthy forests are more resilient to wildfires and the effects of climate change. Carnivores keep diseased deer and elk from infecting their herds, protecting the health of their prey. And since deer fearful of mountain lions avoid venturing too far into the open, mountain lions help protect our orchards, farms, and gardens.

All of this may be cold comfort to a family and a community recovering from last month’s shocking events. Some may even question the wisdom of coexisting with mountain lions, while others will ask how we can better protect our families.

In part, we can take comfort in knowing that mountain lions far prefer their wild prey — mostly deer, but also rabbits, squirrels, feral pigs, raccoons, and coyotes. With thousands of mountain lions in California, we know of only 20 attacks on humans in the last 35 years. More Californians have been killed by lightning strikes in the same time period. Most risky interactions with humans, including last month’s, happen when a younger lion mistakes a human for the food they want. Older mountain lions generally avoid people, our pets, and livestock. Research in California and elsewhere shows that hunting mountain lions, for recreation or in retaliation for threats to people or livestock, tends to make future conflicts more likely, by removing experienced older lions and leaving room for callow and riskier youngsters.

We can and do co-exist with mountain lions, as humans have in California since time immemorial. The alternative to this coexistence, and the risks it brings with it, is a return to the archaic policy of bounty hunting and wanton slaughter. Those disastrous policies wiped out mountain lion populations everywhere east of the Mississippi except Florida. In a handful of rural counties in the West, adherents to the fringe philosophies made famous by the violent takeover of Malheur Wildlife Refuge in Oregon are attempting to resurrect those dangerous and discredited approaches. But elsewhere in mountain lions’ range, from the tip of Patagonia to the Yukon, people and mountain lions are finding better ways to live together.

There is still much we can do to protect mountain lions. Thousands are killed by hunters across the West each year. Many more are killed by livestock owners who wrongly believe those deaths will prevent further conflict. Many mountain lions, including the Santa Monica Mountain population, cut off by highways from neighboring populations, and as a result face the danger of inbreeding. As houses and roads encroach on the mountain lions’ lands, and climate change and wildfire disrupt the remaining wilderness, they are left with less room to pursue their wild prey and raise their cubs far from humans. Outside of Florida, the species lacks legal protections, but this could change soon in California. The state is considering listing some of the species’ populations as endangered or threatened, a crucial step to ensure their safety now and in the future.

###

Josh Rosenau is a biologist and Conservation Advocate for the Mountain Lion Foundation.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email