California Dreamland: Golden Gate Neighbors

Guest Commentary by Christopher Spatz, President of the Cougar Rewilding Foundation

Chris Spatz discusses a recent trip to Pacifica, California and how attitudes towards mountain lions differ from his home state of New York where officials are opposed to the species’ recovery. Midwestern states with tiny populations of lions continue their intolerance, and most western states needlessly slaughter hundreds of lions each year for recreation. Citizens of California were the first to grant Puma concolor the freedom to teach humans the limits of their habitat, to determine how close mountain lions wish to live near us, to let them be neighbors.

“Sometimes at dusk I sit on my desk and watch sunset-streaked clouds fade away toward Paddy Mountain (where one of the last VA cougars was shot). I wonder how it would be to know a panther crouches there again, yellow eyes gleaming, muscles taut, utterly focused. How it would be to accept the risks with understanding and respect, in return for the rightness. A dank breeze slides down Cross Mountain and a chill rises up my back. It would feel, I think, like freedom.

Mountain Lion: An Unnatural History of Pumas and People

Pacifica, California — Mary Dare has lived in Pacifica since 1977. Raised her children here. Retired here. Each morning she walks the trails and parks of this town of 38,000 tucked between the Pacific Ocean and Sweeney Ridge, the northern tongue of the Santa Cruz Mountains, five miles south of the San Francisco city line: the end of what might be called contiguous open space before urban build-out across the northern peninsula. San Francisco International Airport is three crow-fly miles due east. This is no one’s idea of wilderness.

Three-quarters of residential Pacifica is surrounded by posted mountain lion habitat:

At 7 AM on this classic, misty coast morning, Mary is finishing her walk on a loop in San Pedro Valley County Park. Trails switchback steeply up through dense underbrush and stands of eucalyptus. The weekend rain finds Steelhead trout pushing from the ocean up the swollen creek to their ancestral spawning grounds in the park.

Every one of the dozen people I see this early appears to be well north of Medicare eligibility. A group of three. Most are walking solo (dog walking is not permitted in the park), exchanging greetings as they pass one another — a solitary constitutional not recommended in mountain lion habitat. But a random sample of walkers finds little concern. Yes, they know the cats are here, find their pug-marks and scat and deerkills, even see them from time-to-time, as Mary did one morning, a muscled apparition skirting the edge of the very field we’re standing in. And like the suburban residents of northern New Jersey, who now share their suburbs with 800 lb black bears, the retired residents of Pacifica have taken living with a big predator in stride.

When CRF Vice President John Laundré last year published his peer-reveiwed cougar habitat analysis for the Adirondacks, it was met with skepticism, criticism even, by biologists who said John’s conclusion, that the 6 million acres of Adirondack Park, the largest protected hunk of land in the Lower 48, could support as many as 350 cougars. “Dreamland,” one retired NY biologist called the conclusion. Sure, said the biologist, cougars lived near towns out west, but the bulk of their habitat existed in great blocks of mountainous refuge, far from people, “In contrast,” he said, “there’s people spread all throughout the Adirondacks.” In dreamland, I’m finding, there are mountain lions spread throughout the Bay Region’s 7.5 million people.

The next day, an hour down the peninsula, I’m headed north with Paul Houghtaling and Veronica Yovovich, biologists from the UC Santa Cruz Puma Project, along blessedly sunny (missing back-to-back Northeast winter storms) Rt. 17. The four-lane highway bisects the southern Santa Cruz Mountains, running between Silicon Valley 20 miles south to the coastal city of Santa Cruz. Mountain lions routinely navigate Rt. 17, though the highway and its Jersey barriers remain a major obstacle to cougar life and limb. Scrappy Veronica (she’s also worked with wolves, and rock climbs) has crawled into culverts under Rt. 17 trying to determine if the cats might be using them as crossings. The team’s not sure.

If the road-density and development around CA Rt. 17 reminds me of anything home in New York State, it’s not Rt. 73 between Keene Valley and Lake Placid in the Adirondacks, or even Rt. 28 through the Catskills. Rt. 17 reminds me — nearly identically — of Rt. 17 way down-state, the four-lane that drains north Jersey, coursing through the NYC suburbs of Rockland County northwest into Orange County, traversing the open space corridor of the Hudson Highlands, where the ‘burbs end abruptly and Sterling Forest, Harriman and Bear Mountain State Parks begin. Dreamland.

We arrive on the east side of the Santa Cruz to monitor a female and her litter of kittens in the hills above Los Gatos (Spanish for, no kidding, the cats). Her home-range is contained by an open space preserve and county park abutting abruptly the residential, southwest corner of Silicon Valley. As we rise slowly on dusty fire roads into the hills, past mountain bikers and runners and lounging retirees, downtown San Jose — home to nearly 1 million — emerges less than ten miles distant.

Paul, then Veronica, try locating the mother’s position with a hand-held antenna unsuccessfully from several locations. I ask, and Veronica tells me about her research studying oak seedlings, sure enough, becoming saplings from pumas shepherding deer around the Santa Cruz. Understory regeneration is virtually absent in our white-tail bursting, de-fanged forests back East.

Back out on the edge of town, opening and closing access gates, a quarter-mile from a residential development, a hundred yards from the recreation-fire road, under nothing more than dense cover (and, yeah, poison oak), we find the den.

Back out on the edge of town, opening and closing access gates, a quarter-mile from a residential development, a hundred yards from the recreation-fire road, under nothing more than dense cover (and, yeah, poison oak), we find the den.

The kittens are dead. They’re gathered up for a necropsy. Nope, life ain’t easy along the suburban margins, but persistent breeding remains a sign of sustainable mountain lion habitat an arrow-shot from the 33rd wealthiest municipality in the United States.

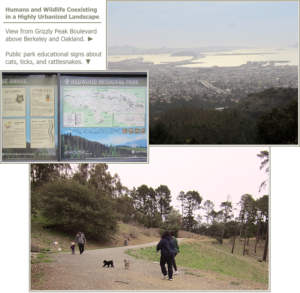

During the rest of my vacation, I track posted mountain lion habitat along the edges and hills of the Bay, from the cattle, elk and deer-dappled coastline — and what a coastline — of Point Reyes (the rangers tell me, as Paul and Veronica did, that there is no problem with puma cattle predation), to the skyline green-belts above Berkeley and Oakland, where thousands every day recreate along Grizzly Peak Boulevard in Tilden and Redwood Regional Parks.

With uncle Dave and aunt Martha, my brother, Pete, and his girlfriend, Dori, we go for a hike half-way down the peninsula in the redwood glades of Butano State Park. About an hour up-creek, Dori, who once led wildlife watching tours of Alaskan brown bears on Admiralty Island, spots a hefty mountain lion turd.

Get the picture? From the relatively remote Grasslands-meet-the-Sea cattle ranches at Point Reyes, to the very edges of urban Oakland and San Francisco, to the trophy-home hills above Silicon Valley (see the Puma Project’s tracker maps) people and mountain lions share habitat all day, every day.

After a generation since mountain lion hunting was twice-banned by voter referendum in California, a generation in which the residents of the Golden Gate have been recreating foot to paw with cougars, there has not been a single incident in the Bay Region between a person and the big cats. While there are state protocols for dealing with cougars temporarily stuck or treed in residential areas, there’s no policy of treating a cat who enters town boundaries — as we see in the Dakotas and Nebraska — like marauding invaderswith automatic, lethal force. No one I talk to appears to feel besieged, as we hear in accounts and testimony from residents of the Prairie States — despite the best education efforts by state biologists like Nebraska’s Sam Wilson — and who live with a fraction of the cats in far emptier landscapes. The boundary between civilization and wilderness has dissolved.

Mountain lions are using nearly every last bit of unfragmented habitat in the San Francisco Bay Region. Wilderness imagined as the definition of where the big predators are, on any given day, could be your backyard. Mountain lions are neighbors.

There is no fantasy of cougar habitat restricted by road-densities, as imagined for the mighty Adirondacks. No management plan that imagines cougars must stay in “suitable habitat” determined by game agencies for cougars, or that sport hunting is a best-practice control. No fantasy between suitable public space habitat — a national forest, say — and unsuitable private space, like ranch lands. Why?

Because the brave and generous citizens of California were the first to grant Puma concolor the freedom to teach humans the limits of their habitat, to determine how close mountain lions wish to live near us, to let them be neighbors:

On Cesar Chavez Street, deep in the urban wilds of San Francisco (named, of course, for Francis of Assisi, the patron saint of animals), there is facing the street a mural painted on a wall of the Leonard R. Flynn Elementary School. The word NATIVE is embedded in the California landscape, from the Sierras to the Pacific, and anointed with the critters of the state, from eagles to seals, from turtles to herons. Front and center, reclines the puma:

Turns out the big critters, too, will creep in close to listen, when we let them. After all, are all the critters not citizens of this great nation?

From the city of Saint Francis, and the state of neighborly mountain lions, it sure feels like Freedom.

Christopher Spatz

Special thanks to the Puma Project’s Chris Wilmers, Paul Houghtaling and Veronica Yovovich for letting me tag along.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Send Email

Send Email