In New Mexico’s legal code, Puma concolor is generally referred to as “cougar.”

Species Status

The species is classified as a game mammal, along with javelina, American bison, wild goats, wild bighorn sheep, Barbary sheep, kudu, Oryx, American pronghorn, elk, deer, pikas, squirrels, red squirrels, marmots, and bears. New Mexico’s Wildlife Conservation Act applies to mountain lions. The Wildlife Conservation Act does not limit itself to non-game species and includes over-utilization for sporting purposes as a factor that may jeopardize a species’ prospects of survival within the state.

State Law

Generally, treatment of wildlife in the State of New Mexico is governed by the New Mexico Statutes – the state’s collection of laws. Since our summary below may not be completely up to date, you should be sure to review the most current law for the New Mexico.

You can check the statutes directly here. These statutes are searchable. Be sure to use the name “cougar” to accomplish your searches.

The Legislature

The New Mexico Legislature is a part-time, bicameral legislature. The lower chamber, the House of Representatives, consists of 70 members who serve 2-year terms. The upper chamber, the Senate, is made up of 42 members who are elected to 4-year terms. Information on finding your state legislators can be found here. The Democratic Party has controlled both houses of the New Mexico Legislature since at least 1992. The legislature convenes on the third Tuesday in January each year. The legislature’s regular sessions last 60 days in odd-numbered years and 30 days in even-numbered years. The governor may call special sessions and the legislature may also call special sessions when three-fifths of each house’s members petition the governor to request one. Special sessions may only last 30 days.

State Regulation

The New Mexico State Game Commission sets the regulations found in the Natural Resources and Wildlife section of the New Mexico Administrative Code – the state’s collection of department regulations. Along with mountain lions, the rules contain provisions for the hunting of deer, elk, pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep, ibex, Barbary sheep, Oryx, turkey, javelina, bear, furbearers, and upland game.

New Mexico State Game Commission

The New Mexico State Game Commission is a seven-member board appointed by the governor and confirmed by the state Senate. When the governor appoints commissioners, their terms are designated one-, two-, three-, or four-year terms so that no more than two commissioners’ terms expire during the same year. At least one commissioner must manage and operate a farm or ranch that raises at least two species of game animals. At least one commissioner must have a demonstrated history of involvement in wildlife and habitat protection issues and whose activities or occupation are not in conflict with wildlife and habitat advocacy. No more than four commissioners may be from the same political party. The commission is tasked with providing a system for the protection of game and fish in New Mexico and using and developing natural resources for public recreation and food supply.

New Mexico Department of Game and Fish

The New Mexico Department of Game and Fish (NMDGF) enforces the state’s wildlife laws and the New Mexico State Game Commission’s regulations. The NMDGF is a department within the executive branch of the New Mexico government.

Hunting Law

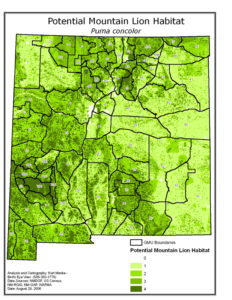

Hunting of mountain lions is allowed in the State of New Mexico. The regulations governing “recreational” hunting of mountain lions specify 19 Cougar Management Zones. Mountain lion hunting season runs from April 1 to March 31 or until a unit’s mortality limit or female sub-limit is met.

Hound hunting is allowed.

Mountain lions may be hunted with center-fire rifles and handguns, 28 gauge or larger shotguns, muzzle-loading rifles, bows, and crossbows.

The State Game Commission sets New Mexico’s “mortality limit”. New Mexico sets sex-specific quotas and prohibits the killing of kittens and any female accompanied kittens. In management zones in which the commission wishes to increase the mountain lion population, the limit is set at less than or equal to 17% of the area’s mountain lion population and no more than 30% of its female population. In management zones in which the commission wishes to decrease the mountain lion population, the limit is set at less than or equal to 25% of the area’s mountain lion population and no more than 50% of its female population.

Depredation Law

Depredation law in New Mexico is monitored by the State’s Department of Game and Fish. The law reads: “A landowner or lessee, or employee of either, may take or kill an animal on private land, in which they have an ownership or leasehold interest, including game animals … that presents an immediate threat to human life or an immediate threat of damage to property, including crops; provided, however, that the taking or killing is reported to the department of game and fish within twenty-four hours and before the removal of the carcass of the animal killed, in accordance with regulations adopted by the commission.” There is a government-funded compensation program for losses of domestic animals to mountain lions. Owners of domestic animals do not appear to be required to take certain steps to protect their pets or livestock.

Trapping

On April 4, 2021, New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham signed into law Senate Bill 32, which bans bans traps, snares, and poisons on public lands across New Mexico. Passage of SB 32 also protects outdoor recreationists and their companion animals from cruel and indiscriminate traps, snares, and poisons on public lands across the state.

According to WildEarth Guardians, “Since 2008, private trappers in New Mexico have killed nearly 150,000 native wildlife species such as bobcats, swift foxes, badgers, beavers, ermine, and coyotes. Critically endangered species, such as the Mexican gray wolf, have also been killed and injured in traps, including two wolves caught in traps in New Mexico in the past six months.”

Poaching

Poaching law in the State of New Mexico provides some protection of mountain lions in law, but only as a deterrent. It is rare for penalties to be sufficiently harsh to keep poachers from poaching again. Poaching is a misdemeanor in New Mexico. The first conviction is punishable by imprisonment for up to 6 months and a fine depending on the specific offense: illegally taking, attempting to take, killing, capturing or possessing a mountain lion during a closed season results in a fine of $400 per animal; hunting mountain lions without a valid license results in a $100 fine; exceeding the bag limit results in a $400 fine; attempting to exceed the bag limit is punished by a $200 fine. A second conviction is punishable by up to 364 days of imprisonment and a fine based on the offense: illegally taking, attempting to take, killing, capturing or possessing a mountain lion during a closed season results in a $600 per animal; hunting mountain lions without a valid license results in a $400 fine; exceeding the bag limit results in a $600 fine; attempting to exceed the bag limit is punished by a $600 fine. A third or subsequent conviction is punishable by imprisonment between 90 and 364 days as well as a fine depending on the nature of the offense: illegally taking, attempting to take, killing, capturing or possessing a mountain lion in a closed season results in a $1,200 fine; hunting mountain lions without a valid license results in a $1,000 fine; exceeding the bag limit results in a $1,200 fine; attempting to exceed the bag limit is punished by a $1,000 fine.

Public Safety Law

New Mexico law allows any landowner, lessee, or employee of either to kill any mountain lion on their land that “presents an immediate threat to human life.” The killing must be reported to the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish within 24 hours and before the carcass is removed in accordance with commission regulations.

Road Mortalities

The New Mexico Department of Transportation does not keep records of mountain lions killed on the State’s roads.

Relationship of Mountain Lions to Native Prey

While historic native prey for mountain lions, competition with sport hunters for bighorn sheep has led to a debate over lethally removing mountain lions to increase prey populations. Under state policy, the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish can kill mountain lions that are believed to be threatening the survival of bighorn sheep in any area with bighorn sheep ranges.