On Monday, January 23, 2018 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) announcedthe official removal of the Eastern cougar from the Federal List of Threatened and Endangered Wildlife. The delisting will take effect February 22, 2018.When the Service first declared in 2011 that the eastern cougar was extinct, taxonomists replied that the subspecies never existed. The fact that the Service holds that “the eastern cougar listing cannot be used as a method to protect other cougars” demonstrates a serious flaw in Federal policy affecting species which have been intentionally extirpated across vast areas, damaging human and environmental health, but are not protected because they exist in a sustainable population somewhere else, far across the country.

In 2016, 73 conservation organizations submitted a letter to the USFWS stating that the problem with a decision to delist based on extinction is that no scientific evidence exists that the cougars which once ranged the East are different than other cougars throughout North America. The Service’s insistence that the cougar is extinct and therefore subject to delisting is a spurious argument that cannot be substantiated given the most up-to-date DNA analyses. It is a poor excuse for delisting given that cougars in the Eastern United States continue to meet all of the qualifications for protection under the Endangered Species Act.

“The USFWS cannot declare extinct a cougar subspecies our best science now understands never existed,” said Cougar Rewilding Foundation president, Christopher Spatz in 2016. “The USFWS needs to develop a federal recovery plan for the entire historic range of the North American cougar including the eastern U.S.”

Questions of Taxonomy

Currently, the puma species native to the western hemisphere taxonomically is named Puma concolor (also known as cougar, mountain lion, and panther). Listed as an endangered species in 1973, Puma concolor couguar, the eastern cougar, was just one of 32 subspecies described in 1946. However, genetic research in the 1990s determined there were just six subspecies, including the one that is widely distributed across North America, Puma concolor cougar.

In 2011 the USFWS opened comments on removing the Eastern Cougar from the Endangered Species List. The 2011 USFWS review acknowledges that the 1946 taxonomy of the eastern cougar is flawed. Modern research cannot distinguish between the thousands of cougars living throughout the western U.S. and the rare historic specimens tested east of the Mississippi River. Cougar biologists now generally agree there is a single North American subspecies.

Threats to Recolonization

“This is a simple case of a broadly-dispersed North American subspecies moving to recover its historic range east of the prairie states,” said Lynn Cullens of the Mountain Lion Foundation. “The big cats face no fewer threats than when they were originally listed. Federal action should include, not remove, protections for animals seeking territory within the former range.”

Puma concolor has been extirpated from the U.S. east of the Missouri River and north of Florida.

Puma concolor has been extirpated from the U.S. east of the Missouri River and north of Florida.

Recolonization has been characterized by cougars dispersing from prairie states into the Midwest for a generation, with rare evidence of the cats roaming as far afield as the Michigan Upper Peninsula, Kentucky and even Connecticut.

“The Midwest has been a cougar graveyard for 25 years,” said Spatz, “Females and wild kittens have not been documented east of the Missouri River.”

Potential for Protection

Cougars need federal protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) across their entire historic range. Cougars within their extirpated range meet all of the qualifications for protection under the Endangered Species Act. These include “(A) the present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of the species’ habitat or range, (B) overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes, and (D) the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms through all of the North American puma’s historic, extirpated range.” (Assessment of Species Status, ESA Section 4).

Designation of Eastern cougars as a Distinct Population Segment (DPS) is consistent with the intent of Congress in establishing the classification (61 Fed. Reg. 4722, 2/7/1996). The cougars are “distinct” as defined by USFWS since they are geographically isolated from breeding populations elsewhere in the United States. Second, the puma’s former range east of the Mississippi River and north of Florida presents a significant gap.

Adding to the complexity of the puma recovery effort is the fact that the endangered panther of Florida – until Monday, January 23 listed as a subspecies under the Endangered Species Act – shares the primary genetic makeup of the rest of the U.S. population. In a press release, the USFWS stated that “The Service’s removal of the eastern cougar from the endangered species list does not affect the status of the Florida panther, a separate cougar subspecies listed as endangered, and all other cougars that may be found in Florida, which are protected under a “similarity of appearance” designation to aid in protection of the Florida panther.”

“As the lone surviving cougar population in the East,” said Cullens, “the panther’s federal recovery plan, including reintroductions, is critical to recovery across the southeastern U.S., and the panther should remain fully protected by future USFWS decisions.”

The Value of Cougars

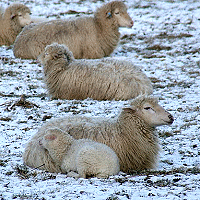

A 2016 scientific paper gave a strong boost to the human value of a federal recovery plan for cougars when it pointed out that deer in the U.S. (the cat’s main prey) cause 1.2 million deer-vehicle collisions annually, incurring $1.66 billion in damages, 29,000 injuries, and over 200 deaths. As many as 20 human deaths could be avoided annually if mountain lions were restored to the East.

And mountain lions contribute to the viability of other species and the environment generally. In 2017 Mark Elbroch published research showing that mountain lions contribute to over 3.3 million pounds of carrion to scavengers within North & South American ecosystems every day — that’s half a million pounds more than the amount of beef McDonald’s serves nationwide. 39 different bird & mammal species in the study area fed on kills left by mountain lions, representing an astounding 15% of local wildlife.Common visitors included usual suspects such as red foxes, but also extended to animals like chickadees, deer mice, and even flying squirrels. Myriad invertebrates, fungi, and bacteria that benefit from carcasses as well. Additionally, all that decomposing organic matter returns essential nutrients and elements to soil so that plants may take them up and start the nutrient cycle anew.

“Pumas are one of the most important ecosystem regulators we have,” notes Greg Costello of Wildlands Network in 2016. “When people see the economic and safety value of big carnivores doing their natural work, we’ll all benefit.”

Repercussions

Unfortunately, the delisting may enable individual states greater latitude to kill mountain lions as they re-establish populations in the East. Nebraska, with a recently established mountain lion population of less than 60 statewide, recently expressed its intention to reopen a hunt season on the big cats in 2018. Illinoisis the only state East of the Rockies (other than Florida) that has outlawed killing mountain lions without a state issued permit.

“We can’t rely on a shooting gallery of state laws that encourage everything from unenforced protections to ‘kill on sight’ to no policy at all,” notes Cullens. “State laws are real obstacles, sure as bullets, and cougars don’t see borders.”

For more about the Eastern cougar:

Visit our Timeline to see the steady state by state extinction of mountain lions in the East.

Read our feature article Eastward Ho about the misconceptions and controversy surrounding cougar recolonization.

Wildlife crime is a more common problem in the United States than most people think.

Wildlife crime is a more common problem in the United States than most people think.

Puma concolor has been extirpated from the U.S. east of the Missouri River and north of Florida.

Puma concolor has been extirpated from the U.S. east of the Missouri River and north of Florida.

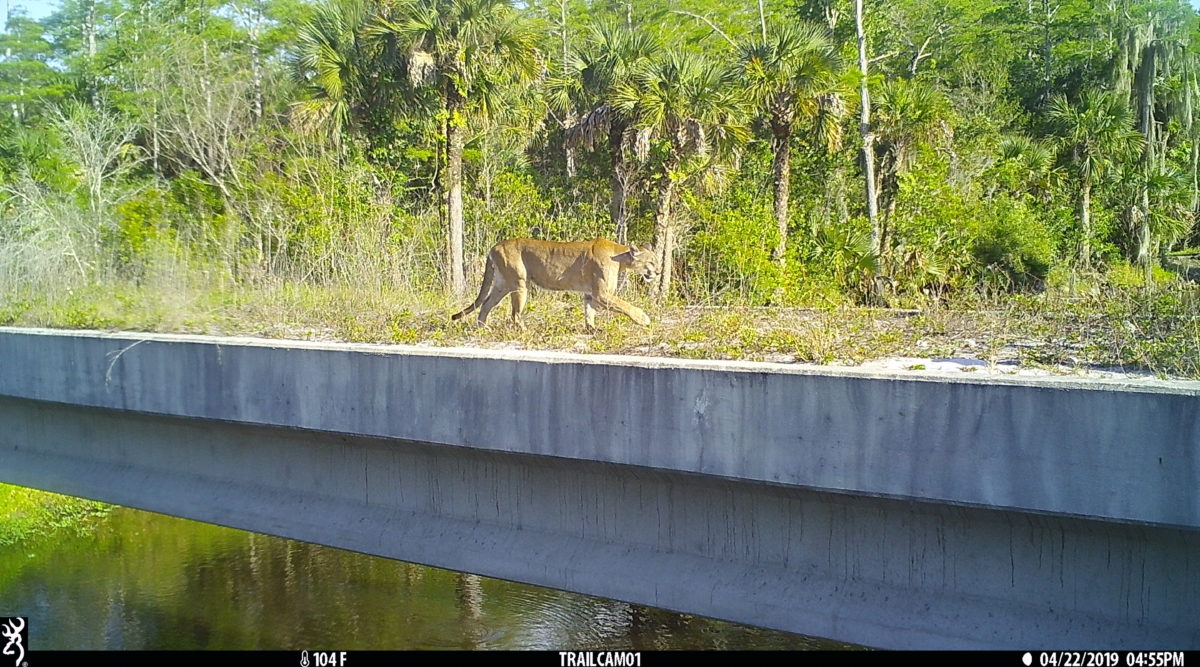

Currently, the team has eleven cameras deployed on the Preserve. Ten of those belong to the Mountain Lion Foundation, on loan for this lion study through a generous grant from the Sacramento Zoo. We’re using Browning Strike Force Extreme Model BTC-7FHD-PX trail cameras. It’s a good camera and gives us the results we want most of the time. We get good day shots and night shots are usually good although they can be blurry depending on how fast the animal is moving.

Currently, the team has eleven cameras deployed on the Preserve. Ten of those belong to the Mountain Lion Foundation, on loan for this lion study through a generous grant from the Sacramento Zoo. We’re using Browning Strike Force Extreme Model BTC-7FHD-PX trail cameras. It’s a good camera and gives us the results we want most of the time. We get good day shots and night shots are usually good although they can be blurry depending on how fast the animal is moving. The most important thing of all! Once you’ve picked a location, mounted a camera and got the batteries and SD card in, test, test, test! We let the camera arm and then one of our crew volunteers goes out in front of the camera to ‘walk like a mountain lion’ to make sure where camera locations will pick up a wildlife movement effectively. If the angle is a bit off, we adjust. And we format the SD cards in the field and test each one, each time on each camera to minimize the possibility of field malfunctions between camera checks.

The most important thing of all! Once you’ve picked a location, mounted a camera and got the batteries and SD card in, test, test, test! We let the camera arm and then one of our crew volunteers goes out in front of the camera to ‘walk like a mountain lion’ to make sure where camera locations will pick up a wildlife movement effectively. If the angle is a bit off, we adjust. And we format the SD cards in the field and test each one, each time on each camera to minimize the possibility of field malfunctions between camera checks.

Mountain lion scat can be anywhere from 6 to 15 inches long and be about an inch or more in diameter. The scat can either be segmented or be one solid piece and segments are blunt-ended but there may be one end that is more pointed. You won’t find any fruit or berry seeds, but there will be hair and bone and maybe some grass. You might find this scat in the middle of a road or path or deposited off to the side. Sometimes, but not always, there will be a ‘scrape’ next to the scat pile, as the lion attempted to cover or mark the scat.

Mountain lion scat can be anywhere from 6 to 15 inches long and be about an inch or more in diameter. The scat can either be segmented or be one solid piece and segments are blunt-ended but there may be one end that is more pointed. You won’t find any fruit or berry seeds, but there will be hair and bone and maybe some grass. You might find this scat in the middle of a road or path or deposited off to the side. Sometimes, but not always, there will be a ‘scrape’ next to the scat pile, as the lion attempted to cover or mark the scat.

One of our most remote cameras is still inaccessible by vehicle or foot and if you need a boat to get to the location, you’re quite unlikely to see a lion floating by. While lions are known to swim, they’re not water babies and will do so generally to escape danger, get to another area of territory, or pursue food or a mate.

One of our most remote cameras is still inaccessible by vehicle or foot and if you need a boat to get to the location, you’re quite unlikely to see a lion floating by. While lions are known to swim, they’re not water babies and will do so generally to escape danger, get to another area of territory, or pursue food or a mate. For the other ten cameras we have deployed, we’re just about to hang the rubber boots up! The water is definitely receding and soon we anticipate that pathways will be dry enough to walk in regular boots. At some of the cameras that still have water close by, we see distinct tracks of coyotes, bobcats, river otters, raccoons and deer. We’ve not seen anything that can distinctly be identified as lion tracks near our cameras besides the area where we placed the carcass cameras.

For the other ten cameras we have deployed, we’re just about to hang the rubber boots up! The water is definitely receding and soon we anticipate that pathways will be dry enough to walk in regular boots. At some of the cameras that still have water close by, we see distinct tracks of coyotes, bobcats, river otters, raccoons and deer. We’ve not seen anything that can distinctly be identified as lion tracks near our cameras besides the area where we placed the carcass cameras.