The Mountain Lion Minutes are a blog authored by Zack Curcija, an Adjunct Professor of Anthropology at Estrella Mountain Community College and Arizona-based volunteer with the Mountain Lion Foundation.

The Archaeology of America’s Lion

The most enduring cultural legacy of the mountain lion in the United States is preserved in the etymology of Lake Erie. Lake Erie takes its name from the common name for the Erie People, an Iroquoian-speaking group that inhabited the lake’s southern shore in present day Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York. To their Wendat (Huron) allies, the Erie were known as Eriehronon or “Panther Nation,” derived from the Wendat yenrish, meaning mountain lion (literally, “long-tailed one”) and ronon, denoting nationhood (Barbeau 1915; Sioui 1999). Early French explorers and cartographers believed this name reflected the high density of mountain lions in the forests around Erie territory, and referred to the Erie People and Lake Erie as the “Nation du Chat” and “Lac du Chat,” respectively (Harder 1987).

Mountain lions appear directly in the rich archaeological record of North America through relatively rare occurrences of claws, teeth, and hide. More commonly, mountain lions are indirectly represented in artifacts and features (e.g. rock art and monumental architecture) in nearly every medium available to ancient North Americans. Mountain lion effigies in wood, stone, clay, shell, bone, and native copper conferred leonine beauty, power, and protection to human beneficiaries. Material culture ranging in size from a carving that could fit in the palm of your hand to the 125-foot-long Panther Itaglio Effigy Mound testify to the prominence of mountain lions in the cosmology and worldview of many Indigenous cultures (Birmingham 2000).

The presence of mountain lion remains in the archaeological record – while rare – establishes that Indigenous people hunted mountain lions throughout antiquity. Ethnographic literature, the use of mountain lion products by historic-era groups, and detailed artistic representations in the archaeological record (e.g. the presence of dew claws in carvings) corroborate some degree of traditional hunting. Historically, mountain lions were hunted by several tribes for their hides, claws, and meat – though mountain lion meat was taboo for some tribes or for individual members of specific religious groups within tribes that otherwise consumed it (Hamell 1998; Kuhnlein and Humphries 2017). The extent to which Indigenous people hunted mountain lions in antiquity is impossible to determine with accuracy. Considering the broad and unimpeded range of mountain lions at the time of European contact, which is today used as a reference of a “natural” distribution, it’s fair to assume that traditional levels of hunting never approached the industrial-scale persecution the species experienced in recent centuries.

Despite their important role in Iroquoian cosmology and common representation in material culture, mountain lions were – as of a 1998 report – absent in the faunal remains of all excavated Northern Iroquoian sites, among the best-documented archaeological traditions in North America (Hamell 1988). From the Southwest, my region of specialization, I know of only three archaeological sites yielding mountain lion remains, but more than a dozen representations of mountain lions in artifacts and rock art. My inexhaustive analysis reveals that mountain lion remains appear less frequently in southwestern archaeological contexts than some rare exotic items, such as copper bells or macaws imported from present day Mexico.

With such an intimate relationship with their local environment, ancient people probably encountered mountain lions often while travelling, hunting, and collecting resources. However, the paucity of mountain lion faunal remains in the archaeological record suggest that hunting mountain lions with traditional means was nonetheless a difficult and/or rare endeavor. Three variables likely limited traditional levels of hunting from adversely affecting the continental mountain lion population as a whole. Here I will make generalizations of the nuanced details of human societies for the sake of brevity and conveying broad trends.

First and foremost, Indigenous people did not have any cultural or economic incentives to eradicate mountain lions or other predators. Such practices seem entirely incongruent with Indigenous perspectives on the natural world, and humanity’s place therein (Hughes 1976). With the exception of turkeys raised in parts of Mexico and the American Southwest, the only domesticated animal in ancient North America was the dog. Conditions were therefore not fertile to germinate the adversarial relationship between human and predator found on other continents where livestock was raised. Although mountain lions and humans often sought the same prey species – chiefly, deer – mountain lions were not viewed as competition. Instead, mountain lions were venerated cross-culturally for their physical prowess, and material culture associated with the athletic felines was worn or carried to imbue humans with good fortune in hunting and warfare (Hamell 1988; Hamilton 1964).

Further, the population size and density of the pre-contact United States was markedly lower than today. For perspective, the most populous human settlement north of Mexico during pre-contact times was Cahokia, an anomalously large ancient city along the Mississippi River that was home to approximately 15,000 people at its zenith between 1050 and 1200 CE (Jarus 2018). Before the advent of agriculture, most people in North America lived in small and mobile band-level societies, as did forager communities across the globe throughout the bulk of human history. Once maize agriculture spread into what is now the contiguous United States, the landscape became a mosaic of relatively large and sedentary population centers – large villages rarely exceeded 1,500 people – surrounded by smaller horticultural villages and even smaller nomadic bands retaining a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Thus, there was never an evenly distributed, intensive, and pervasive pressure placed on mountain lions across a wide region at any given time, and the abundant locations of light or nonexistent hunting served as sources to replenish areas that were temporarily strained by heavier hunting.

Finally, much of the modern technology used to aid contemporary mountain lion hunters – such as firearms, spotting scopes, and GPS-collars for specially bred and trained hound dogs – was unavailable to ancient people. In the ethnographic literature, mountain lions were reportedly captured in traps or hunted directly by tracking or in chance encounters (Kuhnlein and Humphries 2017). Methods of direct hunting were limited to the use of handheld spears or close-range projectiles, such as the atlatl-and-dart system and – later – the bow-and-arrow. While the scenthound breeds most commonly used for mountain lion hunting today have origins in Europe, Native American dog breeds were used to hunt bears, so it’s possible dogs were also employed in hunting mountain lions (Kuhnlein and Humphries 2017). Slain mountain lions were treated with respect, and some groups maintained ritual shrines to honor the skulls of hunted cats (Hughes 1976; Parsons 1939).

After more than ten thousand years of Indigenous levels of hunting, the distribution of the mountain lion was restricted only by geographic variables at the time of European contact. Historically, mountain lions inhabited all of what is now the contiguous United States, with low-density or transient populations living above river corridors on the Great Plains and in the most arid regions of the Great Basin and Southwest. Within just three hundred years of the Mayflower landing, Euro-American predator policy had extirpated mountain lions east of the Black Hills, save an endangered remnant population in Florida. The annals of North American archaeology, ethnography, and contemporary Indigenous tradition demonstrate that human beings and mountain lions can successfully coexist – that respect and ample habitat are prerequisites for the continued existence of the honorable mountain lion.

References Cited:

Barbeau, M. (1915) Huron and Wyandot Mythology: With an appendix containing earlier published records. Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau.

Birmingham, R. (2000) Indian Mounds of Wisconsin. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Hamilton, T. (1964) Pueblo Animals and Myths. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Hammel, G. (1988) Long-Tail: The Panther in Huron-Wendat and Seneca Myth, Ritual, and Material Culture. In N. Saunders (Ed.) Icons of Power: Feline Symbolism in the Americas (p. 258-286). New York: Routledge.

Harder, K. B. (1987) French Colonial Names in New York. Proceedings of the Meeting of the French Colonial Historical Society, 11, 19–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45137382

Hughes, J. (1976) Forest Indians: The Holy Occupation. Environmental Review 1(2), 2-13.

Jarus, O. (2018, January 12). Cahokia: North America’s First City. LiveScience. Retrieved January 10, 2022, from https://www.livescience.com/22737-cahokia.html

Kuhnlein, H. and M. Humphries (2017) Traditional Animal Foods of Indigenous Peoples of Northern North America: http://traditionalanimalfoods.org/. Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment, McGill University, Montreal.

Parsons, E. (1939) Pueblo Indian Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sioui, G. (1999) Huron-Wendat: The Heritage of the Circle. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Dr. Patricia Cramer is an independent wildlife scholar. For the past 18 years she has researched wildlife crossing structures and worked to include wildlife concerns in the transportation planning process, with the goal of reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions while promoting wildlife connectivity across landscapes. Her research projects include three national level projects, and work with 14 departments of transportation, mainly in the western U.S. Patricia earned her PhD from the University of Florida in Wildlife Conservation, a Master’s Degree from Montana State University in Wildlife Ecology, and undergraduate degree in wildlife from State University of New York College of Environmental Sciences and Forestry.

Dr. Patricia Cramer is an independent wildlife scholar. For the past 18 years she has researched wildlife crossing structures and worked to include wildlife concerns in the transportation planning process, with the goal of reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions while promoting wildlife connectivity across landscapes. Her research projects include three national level projects, and work with 14 departments of transportation, mainly in the western U.S. Patricia earned her PhD from the University of Florida in Wildlife Conservation, a Master’s Degree from Montana State University in Wildlife Ecology, and undergraduate degree in wildlife from State University of New York College of Environmental Sciences and Forestry.

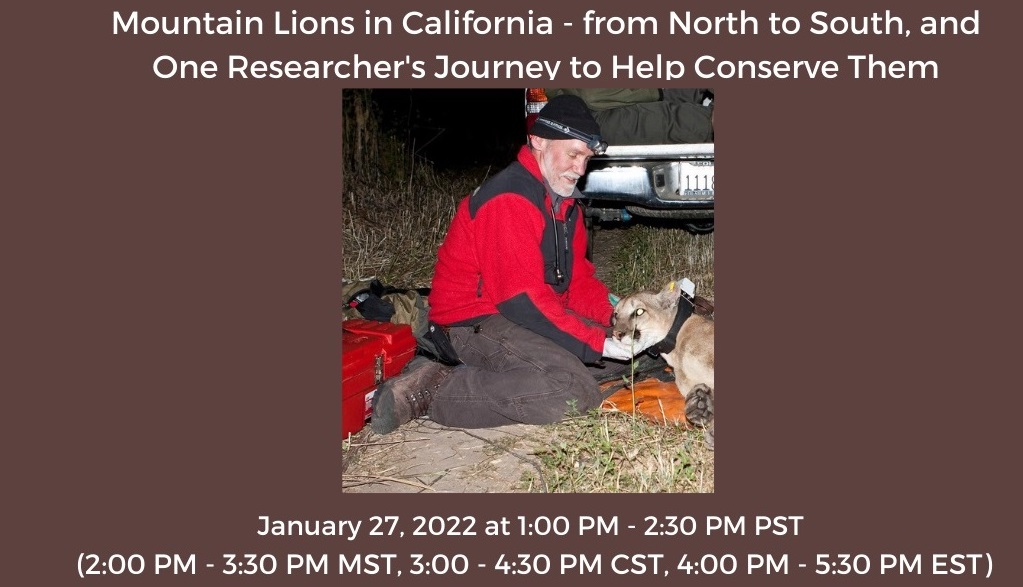

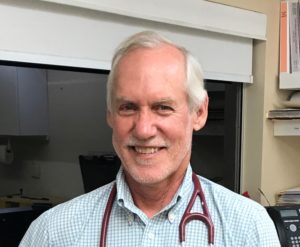

Dr. Vickers is a wildlife research veterinarian with the University of California-Davis Wildlife Health Center and the Institute for Wildlife Studies. He obtained his DVM at Oklahoma State University and practiced on large, small, and exotic species for over 20 years before returning to school to get his Master of Preventive Veterinary Medicine at UC Davis with a focus on wildlife disease and ecology. He has been studying mountain lions and other wildlife for 20 years and directs the UCD Wildlife Health Center’s mountain lion study. He collaborates extensively with other mountain lion researchers, NGO’s, and governmental agencies in the state and elsewhere in the West, and his studies of mountain lions address issues of mortality, connectivity, habitat use, genetics, disease, conservation, and reducing negative interactions with humans and livestock. He also collaborates on studies involving other wildlife species studies, including bobcats, Channel Island foxes, Santa Cruz Island scrub jays and other avian species. He worked for many years with the Wildlife Health Center’s Oiled Wildlife Care Network on oil spill response, and is the author or a co-author of over 35 peer reviewed publications, one book chapter, and numerous white papers and reports to wildlife and other government agencies. He co-developed and directed a 9-part series of short educational documentaries about mountain lions, as well as a one hour film, that have been viewed nearly 1.8 million times and can be viewed here (

Dr. Vickers is a wildlife research veterinarian with the University of California-Davis Wildlife Health Center and the Institute for Wildlife Studies. He obtained his DVM at Oklahoma State University and practiced on large, small, and exotic species for over 20 years before returning to school to get his Master of Preventive Veterinary Medicine at UC Davis with a focus on wildlife disease and ecology. He has been studying mountain lions and other wildlife for 20 years and directs the UCD Wildlife Health Center’s mountain lion study. He collaborates extensively with other mountain lion researchers, NGO’s, and governmental agencies in the state and elsewhere in the West, and his studies of mountain lions address issues of mortality, connectivity, habitat use, genetics, disease, conservation, and reducing negative interactions with humans and livestock. He also collaborates on studies involving other wildlife species studies, including bobcats, Channel Island foxes, Santa Cruz Island scrub jays and other avian species. He worked for many years with the Wildlife Health Center’s Oiled Wildlife Care Network on oil spill response, and is the author or a co-author of over 35 peer reviewed publications, one book chapter, and numerous white papers and reports to wildlife and other government agencies. He co-developed and directed a 9-part series of short educational documentaries about mountain lions, as well as a one hour film, that have been viewed nearly 1.8 million times and can be viewed here (

David & Mary Miller raise lambs and livestock guard dogs on their ranch in Crowley County. They started their own business, Triple M Bar Ranch, in 1994. Triple M Bar Ranch is a family-owned and operated ranch in Southeastern Colorado. They take pride in raising naturally grown lamb and Livestock guard dogs that are born and raised with their sheep. David and Mary are the main ranch hands. Their ranch headquarters sits on Buckeye Hill in Crowley County on the bluffs overlooking the Arkansas River Valley. They also have grazing land in the valley along the river.

David & Mary Miller raise lambs and livestock guard dogs on their ranch in Crowley County. They started their own business, Triple M Bar Ranch, in 1994. Triple M Bar Ranch is a family-owned and operated ranch in Southeastern Colorado. They take pride in raising naturally grown lamb and Livestock guard dogs that are born and raised with their sheep. David and Mary are the main ranch hands. Their ranch headquarters sits on Buckeye Hill in Crowley County on the bluffs overlooking the Arkansas River Valley. They also have grazing land in the valley along the river.

Roy started working as a full-time wildlife photographer in 1991. Spending 6-9 months in the field every year producing natural history content for magazines, books, etc. Around 2000, Roy started leading photo safaris around the world to photography enthusiasts as well as continuing his assignment and stock work. In 2005, Roy became a founding fellow in the

Roy started working as a full-time wildlife photographer in 1991. Spending 6-9 months in the field every year producing natural history content for magazines, books, etc. Around 2000, Roy started leading photo safaris around the world to photography enthusiasts as well as continuing his assignment and stock work. In 2005, Roy became a founding fellow in the

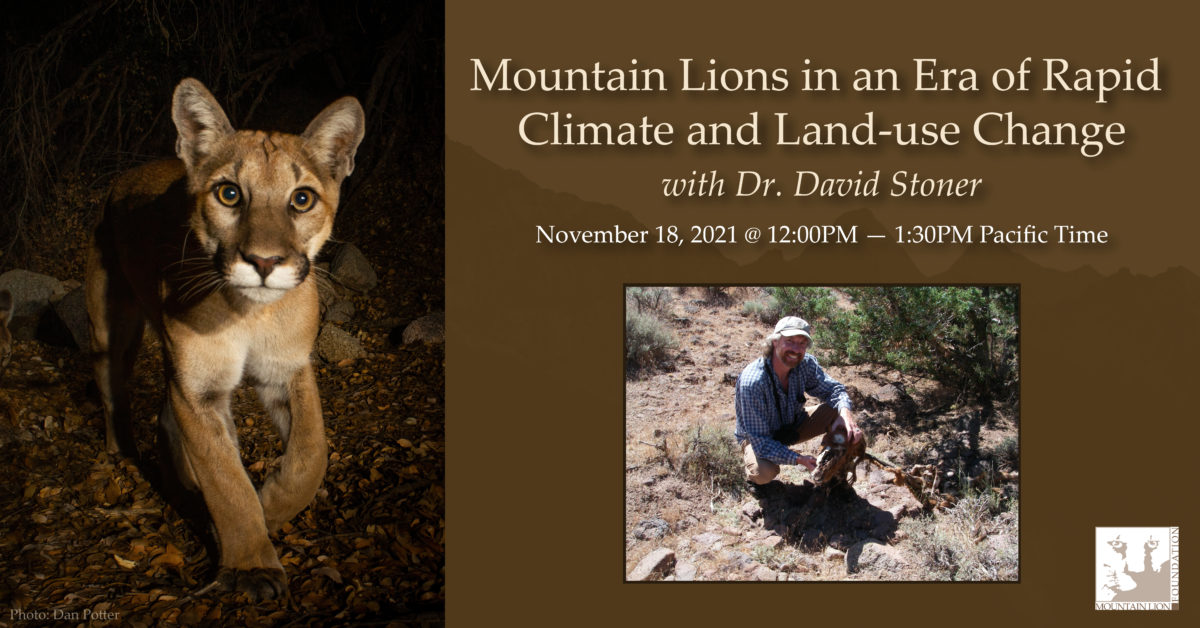

About Dr. David Stoner

About Dr. David Stoner