The first 100 days of the Trump Administration have been characterized by rapid changes across the federal government. Our land, people, and wildlife will all be impacted by these changes—mountain lions included.

Mountain lion populations are heavily impacted by human behavior. Policies at all government levels alter the lives of mountain lions. Recent federal policy directives targeting habitat, connectivity, and scientific research may have some of the most immediate impacts on mountain lions.

Habitat Loss and Degradation

Executive Order: “Immediate Expansion of American Timber Production”

The current president issued an executive order on March 1, 2025, to increase logging in the United States, including in our national forests. The order calls to end the “onerous Federal policies” that have regulated timber production. The order calls for streamlined permitting and increased production by instruction to “take all necessary and appropriate steps consistent with applicable law to suspend, revise, or rescind all existing regulations, orders, guidance documents, policies, settlements, consent orders, and other agency actions that impose an undue burden on timber production.” The order also calls for legislative proposals that would help avoid current regulations and protections of the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

US Agricultural Secretary Rollins has since released a memo that designates 113 million acres of National Forest as open to logging in compliance with the executive order. US Forest Service Regional Foresters and Deputy Chiefs were then directed to develop five-year plans to increase timber production by 25 percent on National Forest lands.

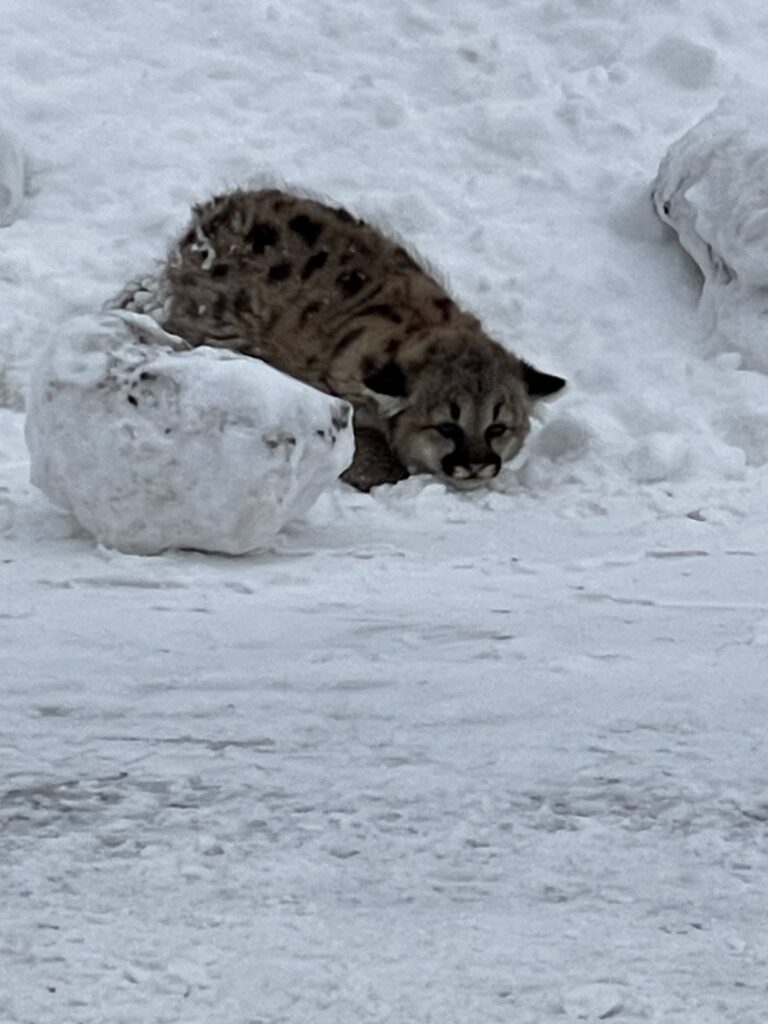

Most of the United States’ National Forests are in the western states and the primary range for our nation’s mountain lions. We don’t know the details of what will result from these orders, but they make clear their intent to prioritize speed and production over caution and environmental protection, which will likely result in the destruction of critical habitat for mountain lions and their prey species.

“Rescinding the Definition of ‘Harm’ Under the Endangered Species Act”

The current interpretation of the Endangered Species Act considers harm to a species as something that causes the species direct harm—such as physical injury—or indirect harm—such as damaging the habitat it needs to survive. On April 17, 2025, the USFWS (United States Fish & Wildlife Service) and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association) released a proposal to rescind this definition of harm, essentially limiting the definition of “harm” only to direct harm.

If this proposal is accepted, critical habitat for endangered species may become available to large-scale agriculture, development, and resource extraction regardless of the peril it may pose to endangered species.

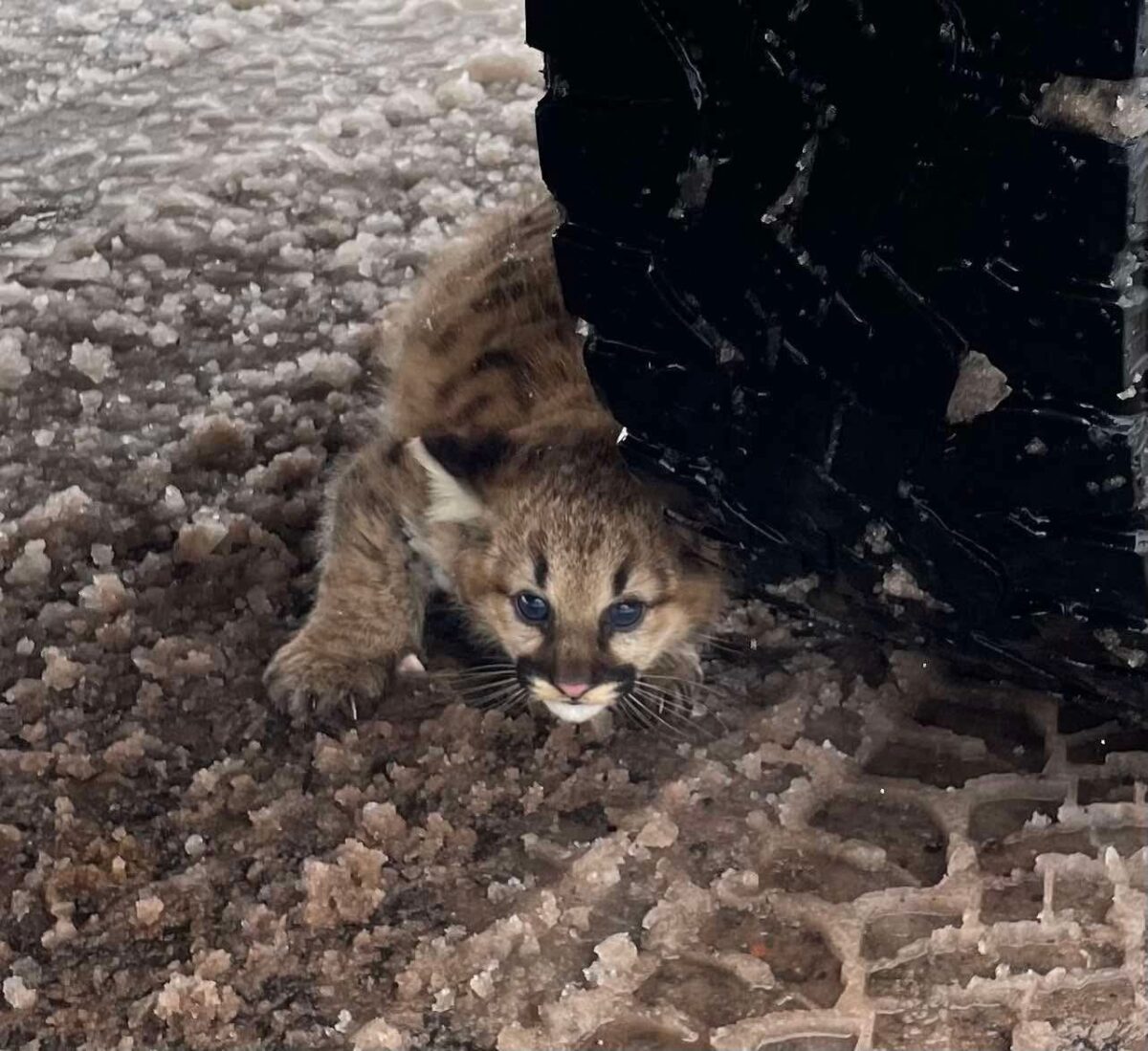

The critically endangered Florida panther is at incredible risk if this proposal is accepted. Florida panthers are the last of the eastern cougar population that was wiped out due to habitat loss and hunting. They were only able to survive in Florida’s undeveloped swamplands. The Florida panther has been on the endangered species list since 1967, and this protection has been part of what has helped the tiny population survive and move towards possible recovery. If their habitat becomes available for development or other uses, the Florida panther may not survive.

Connectivity

Executive Order: “Securing Our Borders”

As discussed in our article on mountain lions along the US-Mexico border, the ongoing construction of the border wall will likely pose risks to mountain lions living near the US-Mexico border. Research along the border wall has been shown to be impenetrable to a wide variety of species, including mountain lions. On January 20th, 2025, President Trump issued an executive order to continue border wall construction.

Mountain lions in South Texas are most likely to be negatively impacted by border wall construction. This population of mountain lions is small, genetically isolated, and faces significant hunting and trapping pressure. The population relies on genetic exchange with mountain lions in Mexico. If lions are unable to cross, they will likely inbreed, which can lead to population declines.

Executive Order: “Unleashing American Energy”

Another common barrier to lion movement is our roads. Across the nation, wildlife crossings provide much-needed links between habitats for mountain lions. In 2021, the passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) included the Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program (WCPP) initiative to grant $350 million to build wildlife crossings across the nation. This policy helps to address the connectivity needs of countless wildlife species, including mountain lions.

On January 29, 2025, the executive order for “unleashing American energy” instructed agencies to “immediately pause the disbursement of funds” for any project funded through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act—including the WCPP. Many of the grants for wildlife crossings are on hold as a result with an uncertain future. The legality of this order has been challenged, with funding being restored in some cases.

Many grantees remain hopeful that the WCPP will not shutter, and funds will return, mainly because wildlife crossings have true bipartisan support. In the meantime, the funding for these crossings remains uncertain—along with the future of the wildlife that need them.

Threats to Scientific Research

Executive Order: “Implementing the President’s ‘Department of Government Efficiency’ Workforce Optimization Initiative”

Recent executive orders have led to mass firings in the federal work force, and dramatic cuts to funding for scientific research. Most of these cuts to employees and funding have been carried out by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE).

The federal employees at agencies like the USFWS and National Parks Service monitor and study mountain lions, educate the public on them, and manage and care for the public lands where they live. Without these employees and their work, our ability to learn about mountain lions and actively maintain their habitat may be at risk.

Executive Order: “Implementing the President’s ‘Department of Government Efficiency’ Cost Efficiency Initiative”

In addition to federal employees losing their jobs, cuts to scientific research also poses deep threats to mountain lions. Many of today’s most important studies on mountain lions are supported by federal research grants. These grants enable not only basic research on the species, but also studies to understand lions’ ecological impact, how humans are impacting mountain lions, and research on coexistence strategies. With less money to go around and fewer scientists able to join the field, much of this critical work may not continue or even begin at all. Threats to mountain lions may go unobserved and unrecorded, and discoveries about the species may not happen.

A Difficult Time for Lions

The rapid pace of change during the Trump Administration’s first 100 days have culminated in uncertainty and confusion. This assessment of new federal policies that could impact mountain lions is not exhaustive nor complete and will likely evolve as these policies unfold. Moreover, this discussion of short-term impacts doesn’t touch on the longer-term impacts of recent policy changes on the pace and severity of the climate crisis, which will certainly affect the long-term survival of mountain lions in the wild.

When considering how federal policy may impact mountain lions, consider if it might negatively impact their habitat, their ability to move across the landscape, or researchers’ ability to monitor and observe their populations. If the answer to any of those is ‘yes’, the policy is likely a threat to lions.

Here at the Mountain Lion Foundation, we will continue to monitor how changes to federal policy impacts mountain lions, and we will continue to advocate on their behalf. Click here to make a donation to support the Mountain Lion Foundation’s education, advocacy, and coexistence work across the country.