Why Hunting Isn’t Conservation, and Why It Matters

By Kevin Bixby, Originally published by The Rewilding Institute, and reprinted with permission

In late December 2014, I received a call from a friend. He and his wife had made a gruesome discovery while exploring the desert outside of Las Cruces. They had stumbled upon the bodies of 39 dead coyotes.

I knew what had happened.

Wildlife killing contests are just what the name suggests. Participants compete for prizes to see who can kill the most coyotes, bobcats, foxes or whatever the target species happens to be. The animals are not eaten, nor are their pelts generally taken. They are simply killed for fun and profit. After the prizes are awarded, the victims are unceremoniously dumped, often by the side of the road.

The coyotes my friend found had been shot in a killing contest held the previous week by a local predator hunting club. I had been tracking the group on Facebook. “Smoke a pack a day” emblazoned over a photo of a dead coyote was one of their favorite memes.

Normal people find these events abhorrent. The hunters I know do not participate in them and tell me privately that they find them distasteful. But few hunting organizations have taken a public position against them (1), and many, like the Sportsmen’s Alliance and Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, oppose efforts to ban them. The fact that the public face of the hunting community condones wildlife killing contests, and that these competitions remain legal in all but six states, is emblematic of the deep divide over wildlife management in the U.S. today.

A System in Need of Reform

It is sometimes said that hunting is conservation. The idea is expressed in various ways—hunters pay for conservation, hunters are the true conservationists, hunting is needed to manage wildlife—but they all suggest that hunters, and hunting, are indispensable to the continued survival of wildlife in America.(2)

As an occasional hunter who has spent my entire career in wildlife conservation, I disagree. Hunting can be many things—family tradition, outdoor recreation, a source of healthy meat–but the claim that hunting is the same as conservation just isn’t supported by the facts.

But there’s more to the statement than harmless hyperbole. The assertion that hunting is conservation has unmistakable meaning in the culture wars.

It has become a rallying cry in the battle over America’s wildlife, part of a narrative employed to defend a system of wildlife management built around values of domination and exploitation of wild “other” lives, controlled by hunters and their allies, that seems increasingly out of step with modern ecological understanding, changing public attitudes and a global extinction crisis.

In August 2018, more than 100 advocates and academics from around the country gathered in Albuquerque to talk about how to transform state wildlife management. It was the first national conference held on the topic.

Some speakers decried the fundamentally undemocratic nature of state wildlife decision making. Others recited the litany of state wildlife management failures, such as sanctioning controversial practices opposed by most people, e.g. trophy hunting and leghold trapping. Underlying all this animus was a shared sense that states are not doing nearly enough to protect wildlife, and that the root problem is the stranglehold hunters, as an interest group, have on state wildlife management.

The issue is hugely significant in conservation circles. States play a critical role in wildlife management, sharing legal jurisdiction over wildlife with the federal government. The conventional wisdom is that the feds are responsible for a subset of organisms–threatened and endangered species listed under the Endangered Species Act, migratory birds protected by international treaties—while the states have authority over everything else (except on Native American lands, where tribes have jurisdiction). Although not everyone agrees with this assessment,(3) the reality in America today is that, for most wild animals, states dictate how they are used, by whom, and if they are protected at all.

So who are the proponents of the hunting as conservation idea? Not surprisingly, they include organizations that promote hunting, such as the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation whose “Twenty-five Reasons Why Hunting is Conservation” is probably the most elaborate articulation of the concept. The hunting as conservation view is also popular with gun groups like the National Rifle Association that like to conflate their second amendment advocacy with a “defense” of the hunting tradition. But it might be unexpected, and disconcerting, to learn that this view is also widely shared by the state and federal agencies charged with protecting America’s wildlife.

What these entities all have in common is a vested interest in preserving the status quo in wildlife management in the U.S.—a system that was developed to a large extent by hunters, is supported financially by hunters, and continues to be operated primarily for the benefit of hunters.

This is especially true at the state level where hunters are disproportionately represented on appointed wildlife commissions, where wildlife agencies overseen or advised by those commissions are staffed largely by people who are either hunters themselves or share their values, and where the opinions of the 82 percent of the public that do not hunt or fish are routinely discounted or ignored.

I want to be clear. Hunters deserve a great deal of credit for their historic role in saving some of America’s “game” species (i.e. species pursued by hunters, such as white-tailed deer, bighorn sheep, elk and pronghorn). Without their organizing and lobbying for game protection laws and their willingness to purchase licenses that generated revenue for the enforcement of those laws, these species might have disappeared. However, the institution of wildlife management that hunters helped to create, and that today exists primarily to serve hunters, is simply not focused nor equipped to meet the extraordinary challenge of preserving species and ecosystems in the face of a mass extinction crisis that is unraveling the fabric of life everywhere.

Teddy Roosevelt and the Rise of the “Sport” Hunter

To understand how the current system came to exist, we need to look at the history of wildlife in America over the past century and a half, a time span that encompasses the most efficient destruction of wildlife in human history. The steady retreat of wildlife in the face of European settlement greatly accelerated after the Civil War, when a convergence of technological, social and economic factors ignited a massive expansion of market hunting to satisfy the demand for wild meat, hides, furs and feathers. In the absence of any effective regulations to control this free-for-all, staggering numbers of animals were killed in the course of just a few decades. An estimated 10-12 million bison in 1865 (5) were reduced to approximately one thousand in all of North America in 1890. Massive numbers of pronghorn, bighorn sheep, elk and deer were also killed. Passenger pigeons were hunted to extinction.

In response, influential recreational hunters like Teddy Roosevelt, George Grinnell, and Gifford Pinchot began to organize in the late 1800s into groups like the Boone and Crockett Club and lobby for game laws to protect the species they enjoyed hunting. Over time, “sport” hunters became a major source of funding for state wildlife agencies through their purchase of licenses and later through their payment of federal taxes on equipment used for hunting and fishing. Hunters remain a significant source of agency revenues today. Not surprisingly, agencies came to view hunters as their most important constituents.

This financial relationship aligned nicely with the prevailing view of conservation during the same period, which was focused on restoring depleted game populations and managing them to produce a “harvestable surplus” for the benefit of hunters. Aldo Leopold, often considered the father of modern wildlife management, defined game management in his influential 1933 book on the subject as “…the art of making land produce sustained annual crops of wild game for recreational use.”

He likened it to other forms of agriculture where various factors needed to be controlled in order to enhance the yield, which, in the case of game animals, included things like regulating hunting and killing predators. This approach led to the successful rescue of certain game species from near extinction.

Although Leopold embraced a more ecological perspective in later writings, much of wildlife management as practiced in the U.S. today still reflects his earlier agricultural view. As the concept of conservation has evolved, state wildlife institutions and policies haven’t kept pace.

We now understand that species interact as parts of ecosystems, and that these systems generate the services—clean air and water, healthy soils, pollination, medicines, etc.—that sustain all life on the planet, including humans. In this holistic view, all species are important.

The context for conservation has changed dramatically as well. The world is currently undergoing a mass extinction crisis in which plants and animals around the world are disappearing at a frightening rate due to a host of human activities. Since 1970, North America has seen a 29 percent drop in bird numbers. Populations of terrestrial vertebrates—mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians—have declined by an average of 60 percent across the globe in this period. Insect numbers are plummeting worldwide. An estimated one million species are now facing extinction. Scientists have called this a “biological annihilation” and warn that urgent action is needed to stop it.

Informed by these facts, the goal of wildlife conservation is, or ought to be, to protect and restore the diversity of life at all levels; but that remains less important to state wildlife managers than ensuring a harvestable surplus of game animals for human hunters. To be fair, most states also have programs to protect endangered and threatened species, but these tend to be underfunded and a lower priority than game management programs.

I would add that any definition of conservation that does not include a measure of compassion and justice for individual animals is out of step with public attitudes, which are moving away from regarding wildlife as strictly a resource for human use and toward respecting wild creatures for their intrinsic right to exist as well. Killing contests are a prime example. While they don’t usually cause a long-term decline in populations of targeted species, and are legal in most states, most people find these events immoral and not in keeping with a conservation paradigm that includes concern for individual animals.

Game Management vs Wildlife Conservation

The on-the-ground differences between ecological-based conservation versus traditional wildlife management are often dramatic. There are countless examples of this, but let’s look at three general categories: exotic species, “nongame” animals, and carnivores.

The introduction of alien species around the world is recognized by biologists today as a major threat to biodiversity. In the past, however, exotic game animals were brought in by state wildlife managers to provide novel hunting opportunities. In my state, the New Mexico Game and Fish Department maintains huntable populations of several introduced ungulates (oryx, barbary sheep, and ibex) despite their competition with native species and the ecological havoc they wreak.

While most states are no longer in the business of importing exotic terrestrial animals, fish are a different story. States continue to raise and stock literally millions(5) of non-native fish in their waters every year, solely for the benefit of anglers. These introduced fish often prey on, hybridize with, or compete with native fishes and harm aquatic ecosystems. New Mexico dumps more than 15 million non-native fish into the state’s waterways annually, all of them predatory species like rainbow trout and walleye. Some of these naïve captive-raised fish, which frequently don’t survive more than a few weeks in the wild because they fall easy prey to human anglers or other predators, have to be obtained from other states to meet perceived demand.

When it comes to fish, state wildlife agencies are, in effect, operating as monopoly industries. They have co-opted a public resource—native aquatic ecosystems—in order to produce a consumer product—fishing opportunities for non-native fish—which they then sell to generate revenues for themselves. (6) The agencies exercise exclusive control over access to their product—you can’t fish in a public water without a license—and their high volume stocking programs maintain consumer demand (“angler expectation”) for their product at a level far beyond what could be satisfied by native fish populations alone. These “put and take” stocking programs sell a lot of licenses, but to say they have anything to do with conservation is ludicrous, and irresponsible, given that freshwater fishes as a group are more endangered and going extinct faster than other vertebrates worldwide.

The divergence in management results is also apparent in how “nongame” species are treated. Prairie dogs, for example, are considered by biologists to be a keystone species because of their outsized ecological importance. Approximately 170 other vertebrate species depend on prairie dogs in one way or another. Conservation-driven management would prioritize their restoration and protection; but in most states where they exist, prairie dogs are considered pests and used for target practice and killing contests.

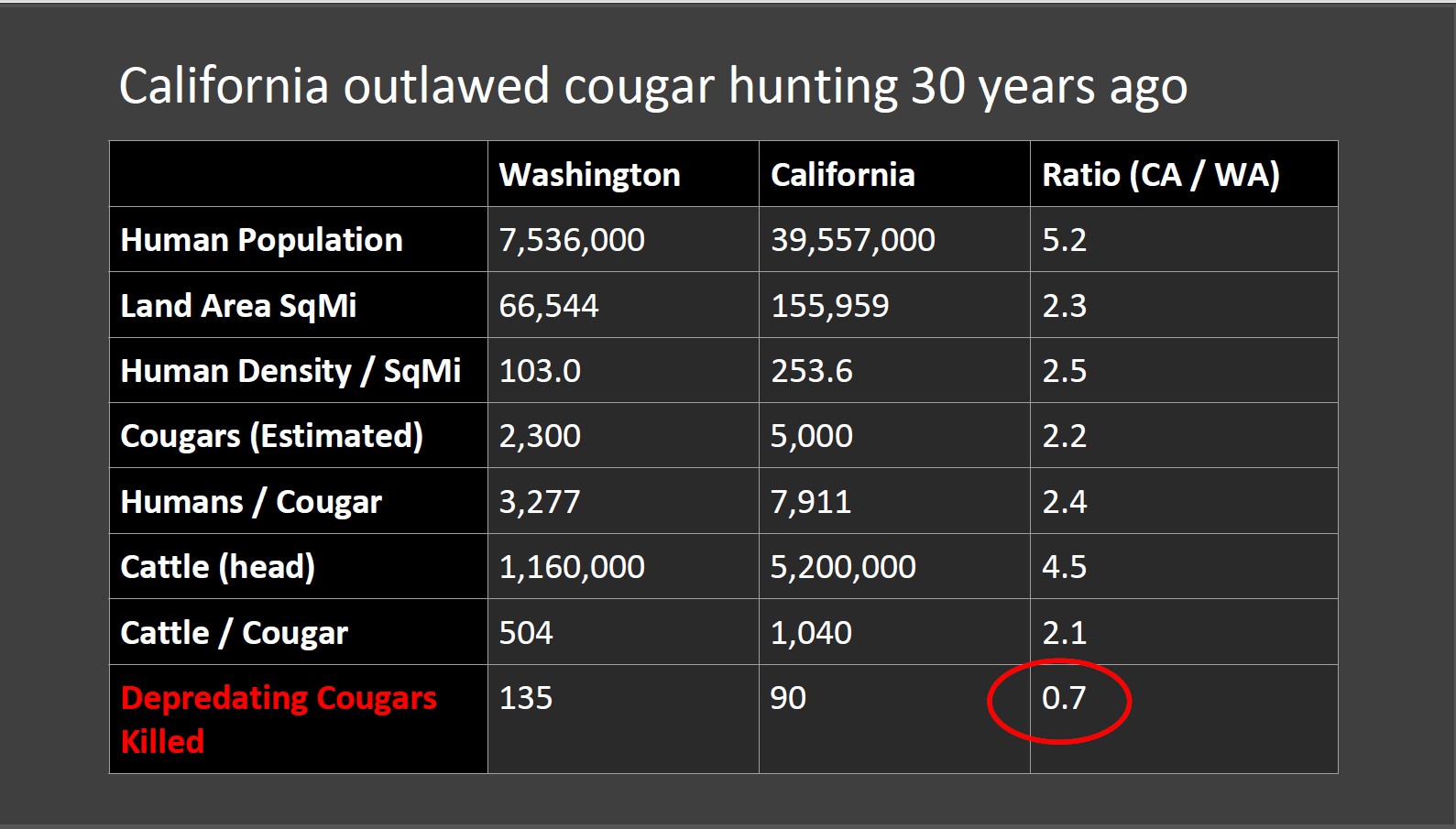

The disparity between game management and ecologically-focused conservation is nowhere more evident than when it comes to native carnivores. Top predators like wolves and mountain lions play a vital role in ecosystems. Most were wiped out from large parts of their historic ranges by the mid-20th century. Conservation would prioritize restoring them as widely as possible across the landscape, but hunting-driven management seeks to do just the opposite.

Carnivores have historically been vilified by hunters and wildlife managers as competitors for game animals and threats to livestock, and that attitude is reflected in state policies today. Coyotes are unprotected and persecuted in most states. Where wolves have been taken off the federal endangered species list, states have responded by subjecting them to intensive hunting and trapping intended to suppress their numbers to keep them just above the level that would trigger federal oversight again. Wyoming allows wolves to be killed year-round, with no limits, over 85 percent of the state. Idaho’s wildlife agency pays shooters to kill wolves in remote wilderness areas and has reinstituted bounties on them.

The argument is often made by defenders of the status quo that, without hunting, wildlife populations would grow unchecked and run amok, but this is not supported by science. Leaving aside the question of what happened in the millions of years before modern humans appeared, there is ample evidence that top carnivores such as wolves, mountain lions, bears and coyotes, regulate their own numbers. They do this by defending territories, limiting reproduction to alpha individuals within a group, investing in lengthy parental care, and infanticide. Hunting is not needed to keep populations of top predators in check; and indeed, it has the opposite effect, because it disrupts the social interactions through which self-regulation is achieved.

Predation can influence the numbers of ungulates like deer and elk, but by which predators? Most state wildlife managers oppose the reintroduction of top carnivores that have been extirpated from their borders, or if they are present, try to keep their numbers artificially low to reduce competition for game animals with human hunters. In essence, then, past and current management policies, driven by antipathy toward carnivores and a desire to improve hunting success, have created a “problem”—scarcity of predators–to which hunting is offered as the only “solution.”

The Myth that Hunters Pay for Conservation

Probably the most common reason for claiming that hunting is conservation, and for justifying hunters’ privileged status in wildlife matters, is that hunters contribute more money than non-hunters to wildlife conservation, in what is usually described in positive terms as a “user pays, public benefits” model. That is, the “users” of wild animals—hunters—pay for their management, and everyone else gets to enjoy them for free, managers commonly claim.

This is disputable. The financial contribution of hunters to agency coffers, while significant, is nearly always overstated.

It is true that hunters contribute substantially to two sources of funding which comprise almost 60 percent, on average, of state wildlife agency budgets: license fees and federal excise taxes. But there are at least three major problems in leaping from this fact to the conclusion that hunters are the ones who “pay for conservation.”

First, as discussed, there is a considerable difference between conservation and what state wildlife agencies actually do. Secondly, even if one assumes that everything state wildlife agencies do constitutes conservation, much of their funding still comes from non-hunters, as explained below. And third, some of the most important wildlife conservation efforts take place outside of state wildlife agencies and are funded mainly by the general public.

State wildlife agencies undertake a wide variety of activities, including setting and enforcing hunting regulations, administering license sales, providing hunter safety and education programs, securing access for hunting and fishing, constructing and operating firearm ranges, operating fish hatcheries and stocking programs, controlling predators, managing land, improving habitat, responding to complaints, conducting research and public education, and protecting endangered species. A substantial portion of these activities are clearly aimed at managing opportunities for hunting and fishing, and not necessarily the conservation of wildlife.

The second problem with saying that hunters are the ones who foot the bill for conservation is that it discounts the substantial financial contributions of non-hunters. To begin with, more than 40 percent of state wildlife agency revenues, on average, are from sources not tied to hunting. These vary by state, but include general funds, lottery receipts, speeding tickets, vehicle license sales, general sales taxes, sales taxes on outdoor recreation equipment, and income tax check-offs.

In addition, the non-hunting public contributes more to another significant source of wildlife agency revenues–federal excise taxes—than is generally acknowledged. These taxes are levied on a number of items, including handguns and their ammunition, and fuel for jet skis and lawnmowers, that are rarely purchased for use in hunting or fishing. Although exact numbers are hard to come by, my initial calculations suggest that non-hunters account for at least one-third of these taxes, and probably a lot more.

Third, significant wildlife conservation takes place outside state agencies, as others have pointed out, and it is mostly the non-hunting public that pays for this. For example, more than one quarter of the U.S. is federal public land managed by four agencies—the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, and U.S. Forest Service. These 600-plus million acres are vital to wildlife, providing habitat for thousands of species, including hundreds of endangered and threatened animals. The cost to manage these lands is shared more or less equally by the taxpaying public. (Hunters also contribute to public land conservation by mandatory purchases of habitat stamps and voluntary purchases of duck stamps, but these are relatively insignificant compared to tax revenues.)

Wildlife for All?

Even it were true that hunters contribute more financially to agency budgets than non-hunters, it’s worth asking if that means they deserve a greater voice in wildlife decisions. Is it fair that one, small user group—hunters—monopolize wildlife management simply because a system has evolved under which their expenditures, opaque (excise taxes) and involuntary (license fees) as they are, end up supporting the agencies tasked with protecting wildlife more than does the non-hunting public? Another user group—wildlife watchers—are nearly twice as numerous as hunters, according to a 2016 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) survey. Yet another “user” group is even larger: all of us, because we all “use” wildlife to keep ecosystems healthy and benefit from the results. Why should these groups be relegated to minority status, or excluded entirely, when it comes to deciding how wildlife is managed?

Under our system of law, wildlife is considered a public trust. Wild animals do not belong to anybody. The government as trustee is expected to manage wildlife for the benefit of the public, including future generations, and balance competing uses to ensure that the trust is not harmed and the broad public interest is served. It is antithetical to this concept that one group would be granted greater access to wildlife because, for whatever reason, they contribute more financially to its management. It would be like saying that only rich people should be allowed to send their kids to public schools because they pay more in taxes.

It is a question of equity. Everyone benefits from wildlife, everyone should share in the cost of protecting wildlife, and everyone deserves a say in determining how best to conserve wildlife. If hunters’ claim that they pay more than their share for wildlife conservation is true, the solution is not to exclude others from a seat at the table, but to find new, more equitable sources of funding to support the work.

Struggle for Power

If the idea that “hunting is conservation” is not factually true, why does it continue to have currency? The answer, I believe, has to do with a struggle over power, identity and values. Wildlife management is now firmly ensconced in the culture wars.

The public is increasingly concerned about wildlife and wants a voice in management, something that has long been the exclusive purview of hunters and their allies. Promoting a narrative that wildlife can’t survive without hunters is part of a larger effort to defend the status quo in wildlife governance by those who currently enjoy privileged status and don’t want to give it up.

As with many other social inequities in America today, the people who hold disproportionate power when it comes to wildlife are mostly white men. Hunters and anglers are 74 percent male and 80 percent white (non-Hispanic), according to the 2016 FWS survey. Looking just at hunters, the demographics are even more skewed. Eighty-nine percent are male and 96 percent are white (non-Hispanic). This demographic bias is reflected at state wildlife agencies where 72 percent of personnel are male and more than 90 percent are white.

It could be argued that the undemocratic nature of the current system of wildlife management is a legacy of its elitist origins in which affluent white men like Teddy Roosevelt played such an important role. The term “sportsmen” was adopted, at least in part, to distinguish men of means who hunted for fun rather than for subsistence or market. The roster of the Boone and Crockett Club in its early years reads like a who’s who of New York high society. These individuals were instrumental in getting laws passed to protect game animals, but one wonders if their influential role in shaping the system that emerged also imbued it with a sense of entitlement for men like themselves.

Efforts to equate hunting with conservation gained momentum in the mid-1990s in response to mounting challenges to the status quo. The number of hunters was declining, relative to the general population. Litigation by advocacy groups to protect species under the federal Endangered Species Act was on the rise. State wildlife managers viewed these lawsuits as a threat to their management authority, and still do.

This was about the time that the Ukrainian-born Canadian wildlife biologist (and hunter) Valerius Geist came up with the idea of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. As he described it in a 2001 article he co-authored entitled “Why hunting has defined the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation,” recreational hunters were the ones who rescued wildlife from extinction, built the system of wildlife management we have today, and continue to make the most significant contributions to conservation. By implication, he suggested that the interests of hunters should be prioritized over those of other stakeholders.

A full discussion of the North American Model is beyond the scope of this article, but suffice to say that it has rapidly become something of a sacred doctrine in wildlife management circles, widely heralded as the premier model of wildlife conservation in the world. The problem is it is both an incomplete framing of history which downplays the contributions of non-hunters, and is an inadequate set of guidelines for preserving species and ecosystems in the face of the current mass extinction crisis. Nonetheless, its unchallenged acceptance within the wildlife management community has helped fuel the narrative that hunting is indispensable to conservation.

It was around this time also that hunters and their allies began to respond to perceived threats to their control of wildlife decision-making by passing right-to-hunt laws and amendments to their constitutions that affirmed the right of their residents to hunt, fish and trap. Adopting language advocated by groups such as the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, these measures often enshrined hunting as the preferred method of wildlife management and protected “traditional” methods of hunting which were often controversial, such as using dogs or bait stations. Alabama was the first to pass such as law in 1996 (excluding Vermont, which passed its law in 1777). At last count, 27 states have enacted them.

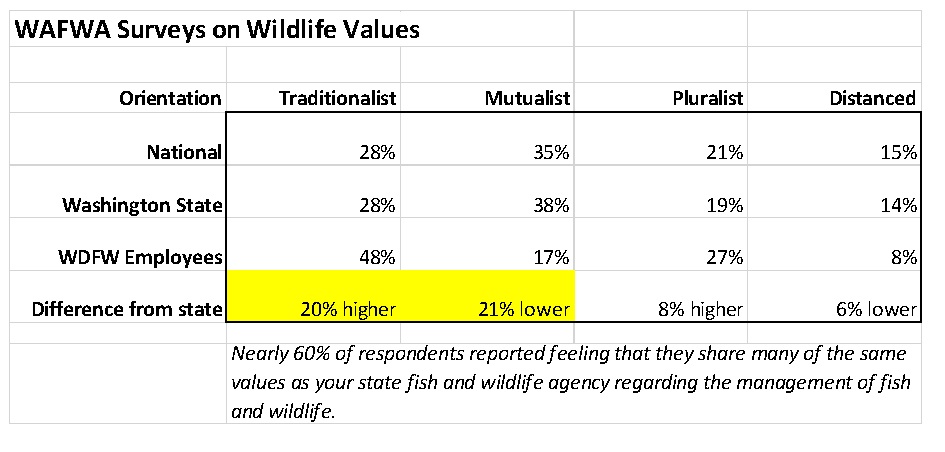

The struggle over wildlife reflects a clash of competing values. In a 2018 national survey, researchers identified two major orientations toward wildlife, which they called domination and mutualism. People with domination values tend to believe that animals are subordinate and should be used for the benefit of humans. Those with a mutualistic bent embrace the idea that animals are part of their extended social network and possess intrinsic rights to exist. These orientations shape not just a person’s attitudes toward wildlife but the way they view the world in general.

Among the general public, more people hold a mutualistic outlook (35%) than domination (28%).(7) The mutualistic orientation has been ascendant in the U.S. at least since 2004, according to the survey. Hunters and wildlife managers, on the other hand, tend to hold a domination orientation—a set of values that are in retreat.

As people tend to do when they perceive their values and personal identity to be under attack, those of the domination perspective resist change. The hunting as conservation narrative is part of that resistance. So too is the strident rhetoric employed by many hunting and gun groups to characterize any perceived critique of the status quo as an attack on their hunting “tradition.” I find the quickness of these groups to attribute even modest proposals for change as representing the spear tip of a chimerical “radical anti-hunting, animal rights” agenda baffling, since the general public overwhelmingly approves of hunting for food, as do most major wildlife groups. Even the Humane Society of the U.S., frequently identified by those in the hunting community as their arch enemy, does not oppose hunting for food.

The domination orientation that prevails among hunters and wildlife managers leaves little room for a definition of conservation that includes consideration of the rights or interests of individual animals. Traditional wildlife management is concerned almost exclusively with the status of animals in the aggregate, i.e. populations and species. Talk of animals having rights–for instance, the right to not be subjected to cruel methods of capture such as leghold traps, or to not have their families broken apart as invariably happens when intensely social animals like wolves and coyotes are killed by hunters–is dismissed as soft-headedness.

Hunters and their allies are quick to assert that wildlife management decisions should be dictated solely by science, not emotion, as if science could adjudicate among what are essentially value matters. Science can tell us, for example, how many mountain lions can be removed by hunters without causing an unsustainable decline in their numbers, but it can’t tell us whether we ought to be hunting mountain lions in the first place. Under our current system of wildlife management, it is simply assumed that if hunters want to hunt an animal, and the species is not endangered, then hunting will be allowed, regardless of public opinion.

This is why wildlife advocates have launched dozens of ballot and legislative initiatives since 1990 dealing with controversial wildlife-related matters aimed at circumventing state agencies and commissions. Not surprisingly, hunting groups and wildlife managers generally oppose these efforts, which they deride as “ballot box biology.”

It is possible to see a connection between the efforts to democratize wildlife management with other social justice movements, such as Black Lives Matter and #MeToo. Just as not all cops are racist, neither do all hunters view the world through a domination lens. But like police, hunters are participants in a system that has its origins in the desire to control and exploit the less powerful, in this case wild animals.

Wildlife Conservation at the Crossroads

For their part, state wildlife agencies face a dilemma. As the already small number of hunters continues to decline, the agencies are threatened with a loss of revenues while facing demands from the non-hunting public to take on more responsibilities. They have two choices. They can embrace a more ecological mission and new constituencies, or they can double down on the status quo by trying to convince more people to take up hunting and fishing.

Many state agencies seem to prefer the latter approach. Every state wildlife agency now has a Recruitment, Retention and Reactivation (3R) program designed to increase participation in hunting and fishing. Nationally, there is an effort to “modernize” the Pittman Robertson Act to allow states to use Pittman Robertson funding for 3R programs, something that is currently not permitted. This is a legislative priority of the Association of State Fish and Wildlife Agencies, which bills itself as the voice of state wildlife agencies.

To be fair, state wildlife agencies cannot magically create new funding on their own. Legislatures have to approve new funding mechanisms, which few have been willing to do.

It’s unfortunate that we’re having this debate in America over wildlife management because it distracts from the urgent business at hand. The challenge of protecting biodiversity in the face of the ongoing mass extinction crisis is enormous. Scientists warn us we have maybe a decade remaining before we reach a tipping point for protecting biodiversity as well as avoiding irreversible effects of climate change. Both are existential threats to human society and life on Earth, and neither crisis can be solved without protecting and restoring intact ecosystems and species. There is a growing call among scientists to prioritize biodiversity preservation on half of Earth’s land area and seas by 2050. This improbably ambitious goal—currently less than 15 percent of land and about 5 percent of the oceans are protected–is increasingly seen as a crucial step for dealing with these interconnected crises.

In contrast to nearly every other nation in the world, the U.S. does not have a national biodiversity action plan. We may never have one under our federalist system. To preserve the diversity of life in this country, we need the states to be leaders, not obstacles, and that won’t happen without a radical reinvisioning of wildlife management at the state level.

The steps in that transformation are clear. It begins with new marching orders. State legislatures need to equip their wildlife agencies with the mandate and legal authority to protect all species, including invertebrates, which are essential to ecosystem functioning. Many states currently lack this comprehensive authority. In New Mexico, for example, the Department of Game and Fish has only been delegated legal authority over about 60 percent of the state’s vertebrates, despite the fact that the state is home to more species of birds, reptiles and mammals than almost anywhere else in the U.S.

Legislators also need to provide their wildlife agencies with the resources to support their expanded missions, including new funding sources that are not tied to hunting. For one thing, it is not fair to saddle hunters with more of the financial burden of protecting wildlife. The public should share this burden broadly. Secondly, state wildlife agencies will be reluctant to embrace a broader mission and new constituencies if their longstanding financial dependency on hunters is not severed.

States also need to democratize wildlife decision-making. In most states, the wildlife agency is overseen or advised by a commission, whose members are usually appointed by the governor. Hunters constitute a majority on most of these boards. If wildlife is a public trust, shouldn’t the general public be better represented on commissions tasked with managing that trust? There will always be a seat at the table for hunters, but it’s long past time to start appointing more people to represent the overwhelming majority of the public that does not hunt.

And finally, state wildlife agencies need to welcome new partners. Preserving nature in the face of the current extinction crisis is a massive challenge. Wildlife managers will need broad public support to be successful, but first they must earn the trust of the non-hunting public.

A good first step is to stop saying that hunting is conservation. At best, this statement acknowledges the historic role hunters have played in protecting America’s wildlife. At worst, it is inaccurate, polarizing, and a distraction from the real work. Like other monuments to the past that now serve to divide, it needs to come down.

-

- Of the more than 50 major hunting organizations that are members of the American Wildlife Conservation Partners, none publicly opposes wildlife killing contests.

- For the purposes of this article, the term “hunting” includes both hunting and fishing.

- One speaker at the conference, University of Montana’s Martin Nie, gave a presentation based on his lengthy law journal article entitled “Fish & Wildlife Management on Federal Lands: Debunking State Supremacy.”

- Per environmental historian Dan Flores in his book American Serengeti. Others have put the number of bison at this time higher.

- Information gleaned from state wildlife agency websites puts the number well over one billion.

- Every state has enacted a law, as a condition of eligibility to receive federal grants under the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program, requiring that revenues from the sale of hunting and fishing licenses cannot be used for anything other than the administration of its wildlife agency.

- A substantial number of people (21%) score high on both scales, while another 15 percent show little interest in wildlife and score low on both scales.

Kevin Bixby is a lifelong wildlife advocate and executive director of the Southwest Environmental Center in Las Cruces, NM. This article originally appeared on the website of The Rewilding Institute, September 2020.

Heeding the urgent call to coexist with mountain lions and other wildlife, today a growing number of professional and hobby farmers are embracing the time-honored husbandry practices that have worked for centuries to keep wild and domestic animals safe. They’re also employing emerging techniques and leading-edge technology and research. This presentation features three panelists with years of on-the-ground experience in keeping people, pets, and livestock safe while peacefully coexisting with mountain lions and other wildlife.

Heeding the urgent call to coexist with mountain lions and other wildlife, today a growing number of professional and hobby farmers are embracing the time-honored husbandry practices that have worked for centuries to keep wild and domestic animals safe. They’re also employing emerging techniques and leading-edge technology and research. This presentation features three panelists with years of on-the-ground experience in keeping people, pets, and livestock safe while peacefully coexisting with mountain lions and other wildlife.

Will Stolzenburg – Discussing Saving America’s Lion September 24, 2020 at 1:00 – 2:00 PM PT, 2:00 – 3:00 PM MT, 3:00 – 4:00 PM CT, 4:00 – 5:00 PM – ET with Q&A afterwards.

Will Stolzenburg – Discussing Saving America’s Lion September 24, 2020 at 1:00 – 2:00 PM PT, 2:00 – 3:00 PM MT, 3:00 – 4:00 PM CT, 4:00 – 5:00 PM – ET with Q&A afterwards.

will be voting on the West Slope Mountain Lion Plan at the upcoming Commission meeting on September 2-3. Thank you to those that already submitted written comments. Now we need YOUR help to ensure that our voices are heard! It is imperative that you provide verbal comments to the commission and speak out against this potentially ruinous plan!

will be voting on the West Slope Mountain Lion Plan at the upcoming Commission meeting on September 2-3. Thank you to those that already submitted written comments. Now we need YOUR help to ensure that our voices are heard! It is imperative that you provide verbal comments to the commission and speak out against this potentially ruinous plan!

Colby Anton, PhD – The Yellowstone Cougar Project

Colby Anton, PhD – The Yellowstone Cougar Project

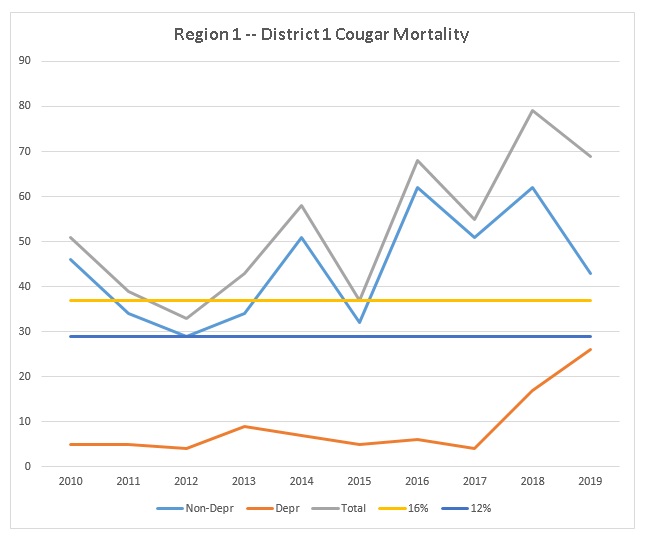

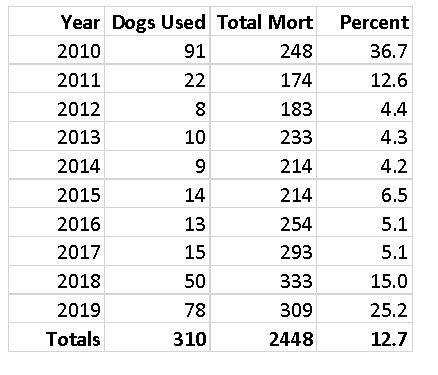

Bob started researching Puma concolor and joined the Mountain Lion Foundation in 2009. The following year, he testified against the Washington Cougar Hounding Pilot Program, formed the Washington Cougar Coalition (WA Cougar), and became the Foundation’s Washington State Field Representative. Since then, he and volunteers have repeatedly stopped bills that would have harmed cougars. In 2013, Bob represented the Foundation on a panel at the 13th Mountain Lion Workshops in Utah. In 2015, Bob spurred WA Cougar to appeal the Washington Commission’s failure to follow proper procedure in setting cougar hunting guidelines. Led by HSUS lawyers, we achieved the first overturn of a citizen commission ruling by a governor in state history. The Commission returned in 2016 to the prior hunting quota. Bob is now working to keep the state from taking measures against cougars in retaliation for the successful return of wolves to Washington.

Bob started researching Puma concolor and joined the Mountain Lion Foundation in 2009. The following year, he testified against the Washington Cougar Hounding Pilot Program, formed the Washington Cougar Coalition (WA Cougar), and became the Foundation’s Washington State Field Representative. Since then, he and volunteers have repeatedly stopped bills that would have harmed cougars. In 2013, Bob represented the Foundation on a panel at the 13th Mountain Lion Workshops in Utah. In 2015, Bob spurred WA Cougar to appeal the Washington Commission’s failure to follow proper procedure in setting cougar hunting guidelines. Led by HSUS lawyers, we achieved the first overturn of a citizen commission ruling by a governor in state history. The Commission returned in 2016 to the prior hunting quota. Bob is now working to keep the state from taking measures against cougars in retaliation for the successful return of wolves to Washington. Utah’s Division of Wildlife Resources (DWR) recently released their proposals for the

Utah’s Division of Wildlife Resources (DWR) recently released their proposals for the