Author: Lace Thornberg

2023 Year in Review

For our December 2023 Living with Lions webinar, we took a look back at a successful year of helping people to coexist with wildlife, advocating for the best possible laws and policies for mountain lions and pushing back against bad and poorly informed policies.

Our event host was Executive Director Brent Lyles, who was joined by our Director of Advocacy Josh Rosenau to field questions from the members and supporters who attended live.

If you are inspired by what you learn, make a year-end gift to set the Mountain Lion Foundation up for success in 2024.

Reflecting on the Legacy of P-22

A Year After the Passing of the Iconic Puma of LA’s Hills

by Josh Rosenau

P-22, the mountain lion who lived in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park for nearly a decade and captured the hearts of Angelenos, died one year ago on December 17, 2022.

As a young mountain lion, P-22 made headlines by crossing two of LA’s massive freeways to find his long-time home in Griffith Park. The freeways that slash through patches of forest in LA’s hills challenge all wildlife but create a special problem for mountain lions. One mountain lion usually needs dozens or hundreds of square miles to find prey, to hide and rest, additional room for mates, and to rear cubs.

National Geographic photographer Steve Winters’ iconic photograph of P-22 in front of the Hollywood sign came to symbolize the strength and courage needed to make that long crossing. It cemented the cat as an A-lister and galvanized a movement to save LA’s cougars.

Like many Angelenos, P-22 made do with a tiny home compared to his kin farther afield. The food scene was excellent, providing all the deer he needed. But like many Angelenos, he found the dating pool limited; without another risky freeway trip, no mates were within reach.

He experienced nearly all the dangers threatening the survival of mountain lions: cars, poisons, humans, shrinking habitat and inbreeding.

Cars, in particular, posed a constant threat to his safety and blocked his access to mates. His plight galvanized public support for a massive wildlife crossing across one of LA’s largest freeways.

The Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing will serve as a legacy that P-22 leaves to all his relations. It is also a testament to the hard work of legislators, state agencies, philanthropists, and mountain lion advocates nationwide. The Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing is already inspiring the construction of more wildlife crossings, particularly in areas where they can help mountain lion populations from becoming genetically isolated. These crossings will help many populations of mountain lions.

Learn more about the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Canyon Crossing: On Crossings

While California had stringent laws to protect carnivores from rodenticides, P-22 needed veterinary care for mange after eating rodenticide-tainted meat. His suffering from rodenticide helped raise the profile of this threat to wildlife and it spurred people to action.

In 2023, wildlife advocates celebrated the passage of Assembly Bill 1322, which expanded the moratorium on rat poison to also include diphacinone, a first-generation anticoagulant rat poison, developed before 1970. This new law, also known as the California Ecosystems Protections Act of 2023, will take effect Jan. 1, 2024.

Read: New law will ban rat poison that was harmful to wildlife

In addition to his secretive life within busy Griffith Park, P-22 was occasionally sighted lounging on sidewalks or apartment staircases nearby. Such close encounters elsewhere can sometimes lead to uninformed and lethal responses, but luckily, his celebrity and good disposition meant people took those encounters in stride.

His easygoing behavior changed in the last month of his life. He was struck by a car, lost the use of one eye, and suffered other injuries that made it hard to hunt. When he attacked several small dogs, wildlife agencies had little choice but to track him (to a backyard) and take him for veterinary care.

During those last weeks, he was lionized by civic leaders, wildlife advocates, and the citizens of LA. Comedians and screenwriters plotted elaborate heists to spring P-22, while strained public relations with LA’s police and sheriff departments produced calls not to snitch on the cat’s location. After it was determined that euthanasia was the cat’s only option, LA’s elected leaders began plans to memorialize the lion with a statue in Griffith Park.

The loss of mountain lions from wild places hurts us all. As we reflect on P-22’s life, it’s incredible to see just how much he inspired people to take conservation action.

The Mountain Lion Foundation is committed to protecting and preserving the presence of these animals throughout their range and we are grateful to everyone who has been moved by P-22’s story.

Taking a Stand Against Unlimited Mountain Lion Hunting and Trapping

Today, the Mountain Lion Foundation and Western Wildlife Conservancy have challenged a Utah law that allows for unlimited, year-round mountain lion hunting and trapping within the state.

In May 2023, the Utah legislature’s House Bill 469 was signed into law by Governor Cox — a bill that, along with allowing for unlimited, year-round hunting of mountain lions, legalized the unlimited, year-round

trapping of mountain lions as well. The law also severely reduces state officials’ ability to prevent these ecologically critical animals from being hunted to extinction in Utah.

We are arguing that this harmful legislation is unconstitutional in Utah. See formal complaint.

“Many Utahns were rightly appalled by this move and believe mountain lions should be awarded more protection, not less,” said Kirk Robinson, executive director of Utah-based Western Wildlife Conservancy, “Our lawsuit is a step toward that.”

“With this hastily written and ill-conceived law in place, it opens up the door for every mountain lion in Utah to be killed,” asserted R. Brent Lyles, executive director of the Mountain Lion Foundation, adding, “Given how critical these cats are to Utah’s food webs and wild lands, the law puts Utah’s natural beauty, wildlife and resources at risk. Understandably, our Utah members and supporters were shocked — someone had to stand up for Utah and its mountain lions.”

As a keystone species, mountain lions (also known as cougars, panthers or pumas) play a critical role in ecosystems, including those in Utah. Mountain lions have more ecological interactions with other species than any other carnivore studied. Their removal will not only harm their prey populations, but also negatively impact insects, birds, plants, and even fish. As noted recently in the Salt Lake Tribune, more than 70% of all Utahns support greater protection for public lands, and cougars are essential to the health and resiliency of those lands, especially in the face of impacts from the climate crisis.

Overhunting of cougars, like that allowed by HB 469, has also been shown by numerous research studies to increase the likelihood of conflict with humans. Since hunters favor larger trophy lions, hunting results in populations with larger percentages of young lions — the most frequent sources of livestock depredations and other conflicts.

The advocates’ legal argument is based on the Utah Constitution’s “right to hunt and fish” provision under Article I, Section 30. Attorney Jessica L. Blome, with Greenfire Law, explained further, “This provision has never been the subject of litigation before, but the plain language is clear: preservation, regulation and conservation are intrinsically intertwined with the right to hunt. Thus, it would be antithetical to both the spirit and letter of the Utah Constitution for the legislature to mandate that mountain lions be whittled down to the point where the species could no longer be preserved ‘for the public good.’”

When lawmakers inserted the cougar-hunting language into HB 469, it happened at the last minute, with little public notice and no clear justification. There was some discussion of cougar populations supposedly growing in number, but those statements ran contrary to research by field biologists.

Utah’s move also stands in contrast to most other Western states, where wildlife managers have ended year-round hunting and outlawed trapping of mountain lions because the practices are cruel and disruptive to the species. Seasons are set to avoid the time when cubs are most dependent on their mothers — by removing those safe windows, Utah’s law will inevitably orphan far more cubs throughout Utah, and the survival rate of orphaned cubs can be as low as 4%. Lacking any other existing regulations regarding mountain lion trapping, cougars in Utah could be left in traps for days, slowly starving, and suffering severe injuries as they attempt to escape. There is also a risk that free-ranging livestock and people’s pets

could be caught in the traps as well.

Photo: Sean Hoover

To support our efforts on behalf of Utah’s mountain lions with a financial contribution, visit this campaign page. If you would like to volunteer to help with this effort, please tell us more about your interests and availability.

Fall+Winter 2023 Newsletter

Read Saving Lions

Read Saving Lions

Our Fall+Winter Newsletter

In this issue, we announce our plans to file suit to protect Utah’s mountain lions, reveal a new ballot initiative in Colorado and share a recap of two new coexistence efforts with much promise.

A print version of “Saving Lions” is mailed twice per year to current contributors. Donate here to receive the next issue at home.

A Dozen Inspiring Conservation Photographers

Bringing talent and passion together for mountain lion conservation

Our 2024 calendar features work by photographers who have gone to great lengths to capture these exquisite images.

Waiting deep in the backcountry hours before dawn. Studiously setting up motion-activated cameras. Coming out empty-handed on countless trips. Trying again.

The Mountain Lion Foundation deeply appreciates their perseverance. We also appreciate that all of these photographers are dedicated to pushing for strong protections for mountain lions and their habitat.

Read on to learn more about the 12 photographers featured and contribute today to receive our 2024 calendar and enjoy their work all year long.

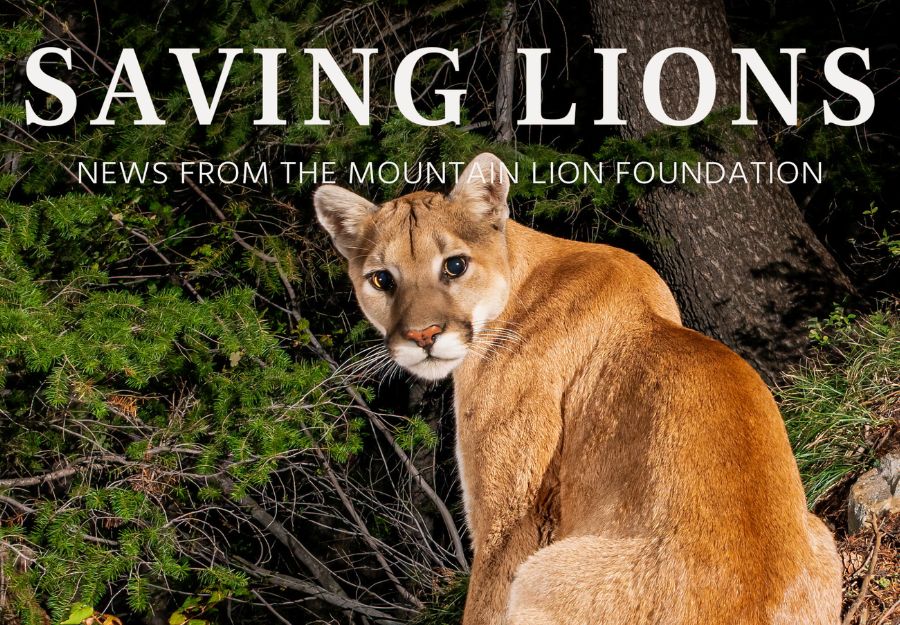

Puma in Patagonia. Photo: Melissa Groo

Wildlife photographer, writer and conservationist Melissa Groo is passionate about educating people about the marvels of the natural world. She believes photography can be both fine art and a powerful vehicle for storytelling; it is her mission to raise awareness and change minds about not only the extrinsic beauty of animals, but also their intrinsic worth. A photo by Groo graces our cover. See more from Melissa Groo.

Mountain lion in Wyoming. Photo: Savannah Rose

Savannah Rose is pursuing her dream of working as a conservation photographer, spending every free moment producing wildlife images. Her favorite subjects are America’s apex predators, such as grizzly bears, cougars, and wolves, as well as the more elusive charismatic mammals, like weasels and pikas. Savannah’s experience as a wildlife tracker gives her a helpful edge, as she can accurately anticipate behavior and share habitat non-obtrusively. See more from Savannah Rose.

For the incredible story behind the image of hers featured, attend our next our Living with Lions webinar on October 18, 2023.

A firm believer in the power of stories to shape public opinion, Amy Gulick uses her images and words to make the case for life on Earth. Her award-winning books include Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest and The Salmon Way: An Alaska State of Mind. She is a founding fellow of the International League of Conservation Photographers. See more from Amy Gulick.

Sebastian Kennerknecht is a wildlife and conservation photographer who focuses on wild cats. Using highly customized SLR camera traps, along with conventional photographic techniques, he works closely with field biologists to effectively and ethically capture photographs of some of the rarest cats on the planet and highlight the threats they face. The rest of the year Sebastian leads international tours to bring people eye to eye with wild cats, including mountain lions, through his company Cat Expeditions. See more from Sebastian Kennerknecht.

Mountain lion near Los Angeles. Photo: Jason Klassi

Jason Klassi is an Emmy-nominated documentary producer and award-winning author. His productions have premiered on television, at the United Nations and at events around the world. NASA, the International Astronautical Congress and Paramount Pictures have published Jason’s writings. He is a recipient of the Space Tourism Society’s Orbit Award. He photographs mountain lions outside Los Angeles. See more from Jason Klassi.

Mountain lion in the Bob Marshall Wilderness. Photo: Steven Gnam

Steven Gnam uses photography to explore and illuminate our connection to nature. His work is a celebration of the wild that encourages protecting our remaining wildlands. He is the author of Crown of the Continent: The Wildest Rockies. A member of The Photo Society, Steven’s work has been featured by National Geographic, The Nature Conservancy, The Trust for Public Land, Nikon and Patagonia, among others. See more from Steven Gnam.

After spending 35 years working with the most advanced aerospace technologies, Dan Potter is now enjoying a retirement assignment of camera trapping mainly in northern Los Angeles County. Along with his support of the Mountain Lion Foundation, Dan also actively supports the Transition Habitat Conservancy, Tejon Ranch Conservancy and the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing.

You can see more of Dan’s camera trap imagery by following the Mountain Lion Foundation on Instagram.

David Willingham is a wildlife photographer, an avid bird watcher and recording engineer. His main photographic subjects are the flora, fauna and landscapes of Central Oregon. You can also find him taking photos at mountain bike races and skate parks.

Jeff Wirth is a conservation filmmaker, photographer and certified wildlife tracker. His strong love for the wilderness, animals, and social and environmental justice have led him to travel the world documenting inspiring stories of the environment and those fighting to protect it. He works and volunteers for organizations working toward a better world, using visual storytelling as his way to make a difference. See more from Jeff Wirth.

David Moskowitz works in the fields of photography, wildlife biology and education. He is the photographer and author of three books: Caribou Rainforest, Wildlife of the Pacific Northwest and Wolves in the Land of Salmon and co-author and photographer of Peterson’s Field Guide to North American Bird Nests. His work has appeared in numerous outlets, including the New York Times, NBC, Sierra, Outside, Science and High Country News. Certified through Cybertracker Conservation, David uses his technical expertise on tracking and other non-invasive methods of studying wildlife ecology to promote conservation. See more from David Moskowitz.

Roy Toft is an award-winning professional wildlife photographer and biologist whose images not only convey a sense of animal spirit but also grapple with changes to our natural world. As a founding fellow of the International League of Conservation Photographers, Roy’s photographs have advanced conservation efforts globally. He is a co-author of Osa, Where the Rainforests Meets the Sea. His work has been featured by National Geographic, Audubon, Discover magazine and many others. Roy lives outside San Diego and leads annual expeditions through his company, Toft Photo Safaris. See more from Roy Toft.

Wildlife and natural history photographer Drew Rush is a regular contributor to the @natgeo and @natgeotravel Instagram feeds. Drew’s home base is in Wyoming and remote cameras are his specialty. Following wildlife has taken him across Asia, South America and North America, through deep forests and high alpine regions. See more from Drew Rush.

Improving the outlook for mountain lions in 2024

As the Mountain Lion Foundation works across the sixteen states with mountain lions, assistance from our steadfast supporters makes all the difference. If you live in a Western state, please let us know if you are interested in advocating for the lions in your state. If you live in a state that mountain lions are resettling, you can help welcome them. Wherever you live you could pledge to give monthly and become a Puma Protector.

However you help, your investment improves the outlook for these majestic, integral animals. Thank you.

Opinion: Colorado’s big cats are not trophies and they shouldn’t be for sale

A ballot initiative would ask voters to ban hunting and trapping of Colorado’s big cats

By PAT CRAIG, CHRISTINE CAPALDO and DAVE RUANE

This guest commentary was originally published in The Denver Post on September 22, 2023.

This week, a diverse statewide coalition — Cats Aren’t Trophies (CATs) — initiated a Colorado ballot measure to end trophy hunting mountain lions, along with fur trapping bobcats. As members of CATs, we aim to introduce the campaign and explain why all Coloradans should support us to qualify this measure for the fall 2024 ballot.

Come November, mountain lion trophy hunting will be afoot in Colorado. Like each year before, trophy hunts will claim as many as 500 lions, with most of the animals shot from trees after being relentlessly chased by packs of dogs fitted with sophisticated radio telemetry equipment.

Prosecutors in the U.S. Attorney’s Office say this photo shows Patrick Montgomery holding the mountain lion he killed on March 31. Montgomery had been released pending charges for his involvement in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol but because the hunt violated the terms of his release, he was placed on 24/7 house arrest. (Photo provided by the U.S. Attorney’s Office.)

Prosecutors in the U.S. Attorney’s Office say this photo shows Patrick Montgomery holding the mountain lion he killed on March 31. Montgomery had been released pending charges for his involvement in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol but because the hunt violated the terms of his release, he was placed on 24/7 house arrest. (Photo provided by the U.S. Attorney’s Office.)

Thirty years ago, Colorado banned hunting black bears with packs of dogs because it’s unfair and inhumane. Lion hunting almost exclusively happens with the use of packs of dogs who attack and chase the lion. Colorado voters don’t want this kind of hunting happening aimed at lions or bobcats.

This is all about trophy hunting, not killing for meat or for management. Trophy hunters pay outfitters as much as $8,000 for a 100% guaranteed kill and are led to the tree after the guide and his dogs have treed the lion. The hunter then shoots the lion off of a tree branch – the moral and sporting equivalent of shooting a lion in a cage at a zoo.

December brings another devastating season for Colorado’s wild cats, as trappers begin their pursuit of bobcats, trapping them alive, shooting and skinning them for their fur. They set an astonishing number of traps throughout Colorado’s wild lands — 4,000 traps in one year alone — and kill about 2,000 each year, according to CPW. Trappers may capture and kill as many bobcats as they can to profit from selling their fur on foreign markets, including Russia and China.

Orphaned bobcats at Boulder County’s Greenwood Wildlife Rehabilitation Center. The four kittens were recently transferred to another facility specializing in carnivores. (Courtesy Greenwood Wildlife)

Change is needed when we step into such unfair, highly commercialized killing of inedible animals.

CATs is a diverse group, encompassing ethical, fair-chase hunters, conservationists, wildlife biologists, scientists, veterinarians, pet shelters, sanctuaries, wildlife rehabilitators, business leaders, eco-tourism operators, ranchers, and farmers from across the state. While our members may hold differing views on politics, we share a strong consensus that trophy hunting and trapping of Colorado’s wild cats are indefensible acts for several key reasons.

Unfair methods: The methods used are grossly unfair and cast a negative light on all forms of hunting.

Orphaned kittens: Trophy hunters always seek the largest adult males, but alarmingly, 41% of mountain lions killed by trophy hunts each year are females, who will be pregnant, have kittens or dependent juveniles the large majority (83%) of their lives. This results in orphaned kittens facing a dismal 4% chance of survival, according to CPW.

Unwarranted body counts: Trophy hunting and fur trapping every year claim the lives of 2,500 animals who are not in conflict with humans or domestic animals. Our measure precisely ends killing for trophies and fur but would not change current practices to manage any wild cat threatening our valued livestock producers and for public safety.

Fake management: Colorado has distinct programs in place to prevent conflict and to surgically handle individual animals identified as a nuisance or as a threat. A good way to think of it is if you have an isolated tumor, you wouldn’t ask a surgeon to remove your uterus, kidneys, and your right hand. That would be malpractice, yet that’s the system of mountain lion exploitation occurring in our state. Science has long told us wild cat populations depend upon available prey and space to live — sport-killing has never proven to be a management tool.

No economic benefit: Recreational mountain lion licenses alone contribute a mere 0.1% to the state’s wildlife operations budget. A tiny percentage of people want to kill animals that are unthinkable to eat, similar to a a domestic tabby — and genetically the same as wild cats.

No public benefit: There is no peer-reviewed scientific evidence supporting the idea that trophy hunting and trapping provide any benefit for public safety, domestic animal protection, or statewide deer population growth for fair-chase hunters. In fact, a body of research, including a study published this year in Biological Conservation, show that trophy hunts increase the risk of human-lion conflicts.

Public disapproval: According to a 2023 study by Colorado State University, 80% of Coloradans disapprove of trophy hunting mountain lions, with an even higher disapproval rate (88%) for using hounds to chase them into trees for a guaranteed kill. Earlier studies fall in line.

Silverton-based photographer Wesley Berg captured rare footage of a lynx in the San Juan Mountains on April 11, 2023. It was his first time to encounter the elusive animal since 2016. (Provided by Wesley Berg)

There are many reasons why we should instead invest in the value of living wild cats. Mountain lions keep deer herds healthy according to CPW researchers, in the midst of rampant chronic wasting disease, which is a massive threat to elk and deer hunting; these cats bring climate solutions and reduce deadly vehicle accidents. Bobcats help reduce rodent populations.

Opponents are going to be those who resist any criticism of any aspect of hunting, anywhere and anytime. Such an approach is detrimental to public support, particularly in a state as independent and free-thinking as Colorado where we do not support exploiting and commercializing our wildlife.

We invite you to join CATs in ensuring that wild cats are treated humanely and respectfully in our state, rather than needlessly destroyed by a few people, for no acceptable reason. Help us preserve our state’s outstanding reputation as a place for recreation and raising families, in an environment that respects all living beings, including our native wildlife.

CATs’ volunteers will begin collecting signatures this fall.

Are you interesting in getting involved in the signature gathering effort? Please let the Mountain Lion Foundation know.

About the Authors

Pat Craig is the founder of The Wild Animal Sanctuary in Weld, Las Animas, and Baca Counties.

Christine Capaldo, DVM, practices veterinary medicine in Southwestern Colorado.

Dave Ruane is an avid naturalist and outdoorsman, a member of Colorado Backcountry Hunters & Anglers and Colorado Bowhunters Association. He lives in Weld County.

From Enthusiast to Advocate

Photographer Cooper Graham shares his transformation story — from outdoor enthusiast to all-out conservationist — and the tale of a mountain lion camera trap project that just keeps growing

By Cooper Graham

Whenever I need to escape the hustle of the city, I head to the woods. I leave crowded streets for the embrace of natural serenity. For most of my life, I felt as though nature was for us. Now I know that nature is despite us. Through short-sighted development and misuse, humans have made it difficult for most of the other species that call our planet home to survive alongside us.

I once had an appreciation for nature. Over time, I have become an advocate for nature’s preservation.

With a goal of saving our natural lands and their native inhabitants, I have come to spend an enormous amount of time in the woods to learn from a species that the entire ecosystem relies on – the mountain lion. This incredible species has taught me about so much more than just natural processes, it has connected my very being to these landscapes.

Backstory: Moving from Iowa to California to Everywhere

In 2013, I left my small hometown in Iowa, bound for the Golden State. My love for the outdoors grew stronger as I explored places I’d read about as a kid. I met my wife and we started our family. California became more of a home than Iowa had ever been. However, I still had the spirit to get out and discover new places. In January 2022, my wife took a job that would allow us to pick up and move every few months, enabling us to see more of the country and have the adventures we always talked about. The only catch: my job. I had started a portrait photography business in San Diego, but now I was starting fresh every three months. As the tedious process of finding clients and paying gigs drudged on, I spent my free time exploring the beautiful wilderness of the Cascades outside of Seattle. I never left the house without my camera and I photographed everything in sight – the lush landscapes, the array of wild animals and even passing hikers, when they were willing. I began to consider shifting my focus from people to nature.

Shifting from People to Nature

My first foray into conservation photography played on both my passion for animals and portrait photography. A friend of mine who had been working with the Judith A. Bassett Canid Education and Conservation Center asked me to fill in for her due to a scheduling issue and I jumped at the opportunity. One key focus of this center, which houses a range of canids, is rescuing fur farm foxes from the brutal trade. To help raise money for the expense of running this non-profit, they offer photography sessions with some of their more mellow domesticated foxes. I immediately fell in love with these rescues and the amazing people that run the center, and I enjoy helping them reach their goals.

As I focused on nature and animal photography, I started to see this world differently. Earth does not exist for us, but our existence is dependent on earth. It brings us life and even has a way of finding purpose in death. I sensed that our poetic relationship with it was collectively fading and I could see a disconnect with humans and the wild landscapes we once relied on directly. Growing up in Iowa, I saw how little remained of the native forest and prairies that once reached from one side of the state to the other. Agricultural use has left little room for wild animals. Mountain lions once lived throughout Iowa, but now you will only hear stories of sightings very rarely and those stories almost always end with the killing of the animal. People have become afraid of having this animal in what they perceive as “their” home. I had an opposite reaction. I dreamed of seeing one of these large cats in the wild. They became one of my favorite species of all time, while living in a place that no longer accepted or allowed their presence.

My Passion Project

I was hiking around Lake Hodges with a friend on an early April morning, when, almost immediately after stepping onto the dirt trail, we saw the distinctive m-shaped track of a mountain lion. As this was the first time I had come across a definitive sign of my beloved mountain lions, I was ecstatic.

In this moment, I realized that my next photography project would be about mountain lions. What I didn’t foresee then was how my idea for a photography project would completely consume me and morph into an extensive research project, but here we are.

For the first steps into my project, I headed to Lake Hodges with one trail camera and a simple plan: I would leave the camera near signs of a lion and hope the big cat would return.

For the first steps into my project, I headed to Lake Hodges with one trail camera and a simple plan: I would leave the camera near signs of a lion and hope the big cat would return.

In these early stages, my time was focused on learning how to employ specific tools and techniques for tracking lions, and not yet on answering any of the biological questions I had. With cougars being so elusive and known to avoid human activity, I was curious as to why I had found tracks on the manmade trail. I remembered back to being in Banff National Park when a ranger there was explaining that bears utilize the trail systems for the same reasons humans do. They provide easy travel through their habitat without having to navigate dense trees and brush all the time.

A month passed, no mountain lions. A sense of failures sent me back to the drawing board to evaluate what I needed to change and what I could add to the process to yield results. I tried again in Pauma Valley but had no luck. I decided to travel up to Palomar Mountain State Park, to be known as RA04(PMSP) for the sake of organization in what was becoming a lengthy process. There I met a park ranger that has become a friend and someone who is always enthusiastic to see new footage and share their own personal experiences with mountain lions. He had told me of an instance where him and his wife were walking around the Boucher Hill area and came across a large tom (male lion) that they tried to haze off the paved roadway, but were met only with a quick glance and then a continuation of the lion to saunter off in his same direction. This told me that the mountain lions in this area were habituated to humans and were aware of their protections in State Park lands. Although this is highly unusual and unheard of, there could be a multitude of reasons as to why the large feline showed no interest in the humans or ran from their presence. This had left me with more questions than anything.

By early May, I had covered the majority of trails in Palomar Mountain State Park and cataloged the signs I’d found along the way. One early discovery was a scrape marking. Mountain lions create scrapes by squatting and using their back paws to push up the top layer of dirt and debris behind them while they urinate on that debris pile. Researchers have found that this behavior serves several purposes. Males are marking their territory and letting transient male lions know of their presence. Females use scrapes to let males know they are in heat and ready to mate. Multiple lions sharing an area will use scrapes to to engage in what is known as “mutual avoidance” (Hornocker 1969). I was almost certain that I was staring at a scrape, but then again, I had never seen one in person before. As I set up my trail camera near this scrape, I daydreamed of coming back and finally getting to witness this elusive creature on the same trails I use. Three weeks passed, the camera yielded no results. Was it time to call it quits and move on yet again?

Frustrated and impatient, I started to doubt everything I had learned up to this point. I had my single trail camera set up on the scrape for roughly three weeks, but only captured a few busy squirrels and a deer every now and then. I decided to go out and pull the camera and move it.

As I checked the footage one last time, I was ready to find nothing and move on. Then came the moment I will remember for years to come. Scrolling through the tiny icons of videos on my phone, I came upon a nighttime capture. The illuminated black and white video showed a figure toward the top of the frame where the trail was. I opened the reel and could barely contain my excitement as I stared at an adult mountain lion using the scrape I had found.

This single mountain lion using this scrape brought a jolt of energy to the project. Suddenly, I was driven to keep going and to go even further. I had so many questions and wanted so many answers. I could feel the project turning from a short-term photography project to a long-term research project as my mind sped through all the things I could potentially accomplish. I had only planned on doing this until I had some sort of hard data (photo or video) of mountain lions I could use to write my article. However, I now saw a bigger potential. Not only could I draw conclusions based off the continuation of capturing video data, but I could use these videos to inspire others to see lions as the important keystone species they are. I’d started this project for the mountain lions and, although I’d had what I’d initially set out for, I couldn’t walk away now.

The footage of the mountain lion utilizing the trail and subsequent footage in the same location started to shed some light on the question as to their use of human developed trail systems. Still leaving the encounter of the park ranger and his wife with the large tom as outlier data, I began to see a pattern in time of day that the mountain lions were active in areas that are heavily traveled by hikers and outdoor recreationalists. Research by scientists and experiences by others who venture out to find these incredible animals have helped me fill the gaps in my knowledge and start to see the full story being told through my own footage. Specifically learning that there is a marked increase in lion activity on north/south ridges where the wind is predominantly from the west/northwest allowing these cats to use their strong sense of smell to work the landscape and locate prey (Neils, 2021). The area in Palomar Mountain State Park is filled with ridges like these and specifically the area shown in the above video. It is likely that the mountain lion shown here is doing just that. Working from the top of the ridge near Boucher Hill down to the Doane Valley and potentially up to another north/south ridge.

As their behavior was becoming more recognizable and second nature to myself, the search intensified and more questions began swarming my mind. I know that with there being a human presence in the area and availability for the mountain lions to take advantage of things like human garbage, pets and livestock, I began to wonder if they were even hunting in this area. I set off to locate an actual kill site. This is where the resources that the Mountain Lion Foundation has shared became extremely useful. From a blog post on the Mountain Lion Foundation website, I learned that lions will sometimes bite the noses of their prey in their fight to subdue the animal and finish the kill (Johnson 2021). This proved to be valuable information when I eventually discovered the skull of a young mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) buck. Upon close examination to find the source of death, I found that the nasal bones had been crushed and the bottom jaw consumed as well as half of the spine and most other bones.

Skull with crushed nasal bones.

Half of a spine and hips remaining with chew marks.

When feeding on deer, lions will often consume the bones of the spinal column as they feed on the large supporting muscles along with other bones and the nutritious marrow within (Johnson 2021). In the photos above, you can see that the bottom part of the skull is gone, the majority of the spinal column and legs have also been consumed. These are all fantastic signs that a mountain lion was responsible for this kill.

When looking at the area, you will also notice that the kill was lying on the western side of a north-south ridge just up from Doane Valley. Proving that the information about their usage of these ridges is important to their behavior and allowing me to hone into the activity patterns of cougars in this area! Let’s look at what this ridge looks like exactly.

My “month-long” project has grown and evolved considerably. It’s now in its sixth consecutive month, and I have up to 10 cameras going at a given time. I am spending loads of time either checking footage, running new exploratory routes or scouring research articles to come up with new ideas for where to look and things to try. My Puma Concolor Project (PC001 and PC002) has a few different focuses in terms of scientific findings, but none of those are more important than the goal of creating a sense of community with other mountain lion lovers and changing the minds of those who do not fully understand the species.

With no end in sight, my obsession with mountain lions is only growing stronger, and this project will more than likely be a multi-year endeavor.

With support from amazing organizations like the Mountain Lion Foundation, my dream of sharing the work I am doing with more people is coming true. Watch their Facebook and Instagram channels to see footage from my trail cameras and stay tuned for more project updates.

Literature Cited

Hornocker, M. G. 1969. Winter territoriality in mountain lions. Journal of Wildlife Management 33:457-64

Neils, D. (2021, March 2). Celebrating wild – where, when and how to look for Mountain Lion Activity. Wild Nature Media. https://wildnaturemedia.com/wildnatureblog/2021/2/28/mountain-lions-where-when-and-how-to-look-for-activity

Johnson, Phil. “Mountain Lion Kill-Site Forensics: Identifying Predation, Scavenging and Kleptoparasitism.” Mountain Lion Foundation, 1 Nov. 2021, mountainlion.org/2020/11/03/mountain-lion-kill-site-forensics-identifying-predation-scavenging-and-kleptoparasitism/.

About the Author

You can see more of Cooper Graham’s work at coopergraham.com or find him on Facebook and Instagram.

California Residents: Urge Governor Newsom to sign the California Ecosystem Protection Act of 2023

We’re so close to saving mountain lions from the rat poison exposure that leads to serious health problems

Seeking artists

Put your design skills to work for cougars

First question, do you love mountain lions? You’re here, so, of course, you do!

Next question, do you have graphic design talent that you could contribute toward helping mountain lions?

The Mountain Lion Foundation is seeking a design for our next t-shirt that will be created in partnership with For the Love of All Things. Submissions will be reviewed by Mountain Lion Foundation Executive Director R. Brent Lyles and a selection of staff and volunteers.

If your design is selected, we’ll send you a shirt in the style of your choice.

What We Are Looking For

-

- Your own original artistic design, suitable for printing on a t-shirt

- A design that features a mountain lion and fosters appreciation and respect for mountain lions, or promotes coexistence with mountain lions

Submission Deadline

-

- October 10, 2023

Submission Guidelines

-

- Maximum 4 colors

- Vector file Ai (Illustrator) or Raster (Photoshop) with only solid colors (no gradients or transparencies)

- No shape less than 1pt thick

- Please submit a JPEG or JPG; maximum 3MB; with a minimum of 1200 pixels on the longest side. Finalist will be asked to submit a file that is 300 dpi & no bigger than 12 in x 12 in.

Submission Instructions

-

- Images must adhere to the following format: JPEG or JPG; maximum 3MB; with a minimum of 1200 pixels on the longest side.

- Please label your file as such: Lastname_DesignTitle. Titles may be shortened to avoid long file names and they should be given without spaces in the file name. (The image titled A Little Cougar in the Rain by Maria Martínez would have this file name: Martinez_LittleCougar.jpg.)

- When completing the submission form, be ready to provide your name, your mailing address, a short bio (under 200 words) and a short description of your design inspiration (under 200 words).

SUBMIT YOUR DESIGN

By entering, entrants automatically accept the conditions of the competition; the winner(s) grant the Mountain Lion Foundation nonexclusive right to use and reproduce images for promotional purposes (e.g. website and social media) No royalties or compensation would be paid for these purposes.

With questions or for further information, please contact crobinson@mountainlion.org.