ON AIR: Toni Ruth on Lions and Wolves and Bears in Yellowstone

An Audio Interview with Julie West, MLF Broadcaster

Listen Now!

Listen Now!

Listen to the interview from MLF’s ON AIR program, podcasting research and policy discussions about the issues that face the American lion.

Transcript of Interview

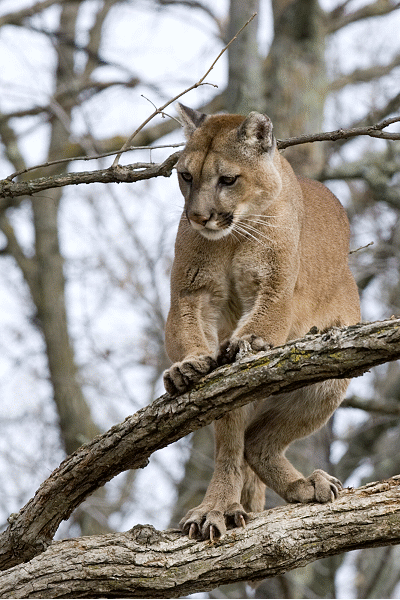

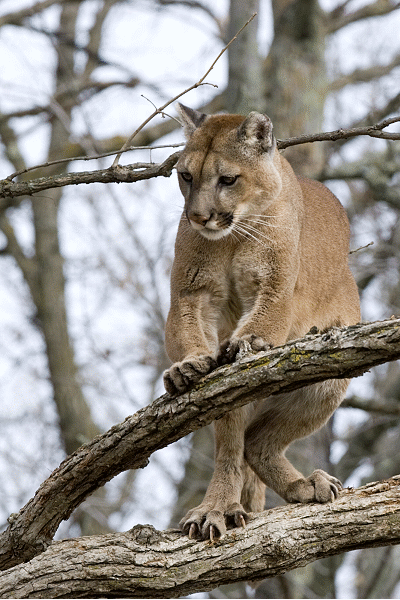

Julie: Hello, I’m Julie West. With me today is Toni Ruth. Toni is a research scientist with the Selway Institute. She is completing analysis and writing from eight years of research on the effects of wolf re-establishment on the cougar population in and near Yellowstone National Park, while working for the Hornocker Wildlife Institute and Wildlife Conservation Society.

Dr. Ruth received her PhD in Wildlife Ecology at the University of Idaho. She has been involved in cougar research and various ecosystems since 1987 and worked with the Hornocker Wildlife Institute for over ten years. Her interests include ecological relationships and interactions between carnivores, prey, and humans, particularly research and multi-carnivore, multi-prey systems. So hello, Toni.

Toni: Hello, Julie, how are you today?

Julie: Very good. Welcome. Well let’s begin by talking about your research on wolves and their impact on the cougar population in Yellowstone. What have you learned about these interactions?

Toni: Yes, well, I think one of the most important things to get across is first of all, our study is pretty unique in that we had a great opportunity to come in after wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone, on the heels of some previous research that was done on cougars prior to wolves being reintroduced. So, there was this great database prior to wolf reintroduction on the cat population and their diet, rates of predation on prey species.

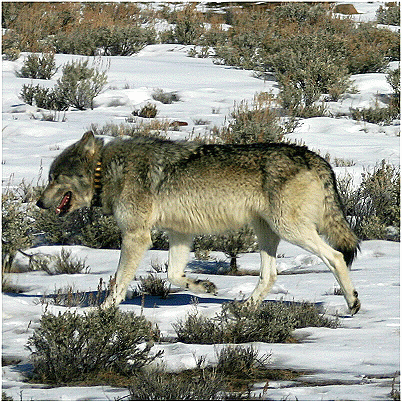

Our study was looking at, you know, what changed once wolves came back in the system. And, kind of how do those two carnivores potentially sort out the landscape. Are wolves so dominant that they out-compete cougars, and cougars are no longer going to coexist with wolves? Or, do they avoid wolves in certain areas of using the resources and the landscape where both are present?

Wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park in 1994.

Like all species, you know, cougars and wolves have a functional role and a position in a community. And this is usually what’s called their ecological niche, which basically consists of all the environmental conditions and resources that are necessary for them to maintain viable populations. And so, we can’t look at all those possible conditions and resources, and we just focus in on the ones that we can potentially measure pretty well. And so, we looked at diet and space and habitat use, and kind of a temporal use of the landscape: how they followed prey seasonally and temporally and whether there’s overlap, and the aspects of their movements.

Cover’s important for them, which functions in for them to be able to hunt and creep up on their prey. And, it also functions as good habitat for them to be able to escape any dominant competitors into, so, forested areas and areas that have really good topographic complexity. And then there’s other spots in Yellowstone which are these huge open valleys which the wolves optimize and use. So we did see some spatial changes after wolves came into the system.

Julie: Everyone makes room for everybody else.

Toni: Yeah, so more cats using the really good cat habitat and shifting out of where you know, wolves became dominant. And that’s not to say the wolves don’t pass through that cat habitat, it’s just really secure.

Julie: Right.

Toni: For the cats.

Julie: And where do bears figure into this scenario?

Toni: Yeah, we did have some information on bears. We weren’t able to… nobody’s really got a real good grasp on either the black bear population — more so on the Grizzly bear population — but not every Grizzly bear is marked.

But they certainly do play a role. The main place that cougars and wolves interact are at kills. There, they kind of function as these epicenters of interaction that attract a bunch of different species, whether it be a wolf kill or cat kill, or just even a winter-killed animal that may provide food to other individuals. And…

Julie: So one animal might initiate the kill and another might ultimately finish it? Or?

Toni: Exactly.

Julie: Okay.

Toni: So, yeah. So cats tend to be subordinate. You know wolves operate in packs, so they tend to be dominant over cats and also bears are dominant to cougars. And when they find these kills and come in on one, then often if the cat’s still there, they’re displaced. Sometimes a bear or wolf may find the cat kill and the cat’s already left and they simply scavenge from it. But you know, that does happen quite a bit.

I think overall, I’m trying to remember what, what our numbers were. We had, I think it was about, wolves is about 23 percent of cougar kills and displaced the cat from about 8 percent of those kills.

And, most of those interactions between cougars and wolves tend to happen during winter when both species are more highly overlapped on ungulate winter range or prey winter range. Everything is kind of — you know — compacted down into a more concentrated area because the snow depths increase at higher elevations. And so, you know, where the prey are is where wolves and cats both have to be. And just in their daily course in movements, wolves are probably more likely to encounter a cat kill during the winter than during the summer months when everything’s a little bit more dispersed on the landscape.

Bears aren’t active during the winter time. They’re in their den, [laugh], and so they aren’t really a factor at that point, but certainly during the summer when bears are out of their dens, they visited about 50% of the cougar kills, and actually bumped the cougar off 22% of their kills that we were able to document. So, you know both of those carnivores benefit pretty greatly from accessing cat kills.

And on the alternative side, that can be somewhat costly to individuals if they’re displaced at a pretty high frequency. But, in general, it’s fairly well distributed across several individuals.

We did notice that one female in particular seemed to get displaced more than other individuals. And interestingly enough, she was [laugh] amazingly, very confident in where she made her kills and how she dealt with the situation. She was a very successful mother. So even though she had high pressure from you know, these other carnivores displacing her, she was a successful individual. And when you think about natural selection and passing on genes, that’s an individual you’d want to remain in a population, because she’s highly successful.

Julie: Right. And is there enough food to go around, based on your findings?

Toni: You know, at the time we did. For the time frame we did our study which ran from 1998 through 2005 — so, to the point that it was almost ten years after wolf reintroduction — there was apparently plenty of food to go around.

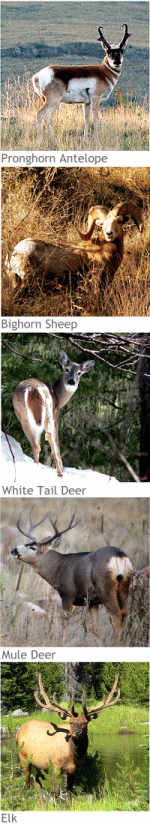

Cats have a little bit more diverse diet than maybe wolves do on a year round basis with the large prey items. We saw them taking pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep, white tail and mule deer, as well as elk being the primary prey, so there were areas that they could access other prey in that steep rocky canyon, not just necessarily elk.

Now that we’re ten years out and some things have changed in the system, you know, food might be a little bit more limiting which can influence and increase, potentially increase, the competition between species as well as within the species.

Some of the more interesting things for me in Yellowstone we were able to observe is, because of that matrix type landscape where you’re walking along the timber and locating a cat, but being able to see out into the open, there’s one female who killed a large bull elk. And we checked on that kill the following day to see if she was still at it and low and behold, there was a grizzly bear on the kill and wolves were right around. So that was within a day that she was displaced from this large prey item that, she made the kill on her own and then had to go on and make a kill again some other time.

Julie: Right. Hopefully she had a head start so she had a full belly.

Toni: Yeah, I’m sure she did, she had to day to feed on it, but…

Julie: [laugh]

Toni: But that’s how quickly sometimes those types of interactions can happen and one of the things we noticed in our research is that those large prey items — when a cat makes the kill like that — they tend to end up out in the open, presumably because maybe the animal is running away and down slope it takes longer for a solitary cat to manipulate that large prey item versus something smaller like an elk calf.

And when those kills end up in the open, they’re harder for them to conceal because they can’t drag them someplace into the cover. So they still cover them with debris but the avian scavengers like ravens and magpies key in on those kills more quickly because they’re in the open. And they tend to attract and draw the other large carnivores, like bears and wolves. And so, those large prey items, even though they could potentially provide more meat for a cat, they also are more difficult for them to conceal.

Julie: I see, I see. And, so it seems like a cougar would maybe very rarely defend its kill then when confronted with a wolf or a bear?

Toni: Yeah, you know, if it’s a one-on-one type thing like a single wolf, there’ve been a couple instances where we know the cat has defended its kill or maybe even killed that solitary wolf, but that’s a more rare occasion than you know, a pack coming in.

So the cat tends to pretty quickly leave and what’s interesting too is that wolves are also more likely to chase a cat where the bear tends to focus in more just on the prey item. So if the cat leaves, then the bear is just going to stay at the kill and feed. Whereas wolves may actually chase the cat and tree it somewhere.

Julie: Okay, and what about mating? Have you gotten to observe a lot of moms with their babies or cougar-to-cougar interactions?

Toni: Yeah we did, there were a couple instances where we were able to locate and observe females with males. And yeah, they’re not just uh, laying around together, but the actual mating behavior and lots of vocalizations. And in one case we were doing a predation sequence on an adult female and over 13 days she interacted with two different males switching back and forth between the two. And her litter of kittens that was produced lined up right with the last two breedings. For a while we weren’t sure which male was the father, [laugh], until we got the DNA analysis back. [laugh].

Julie: Oh how interesting.

Toni: So there was certainly in that case some mate choice going on from her perspective. [laugh].

Julie: Yes, wow, how ’bout that! And when young mountain lions need to leave their mothers and siblings and establish their own range, where they going from Yellowstone? Are you following their progress?

Toni: Yeah, that’s always a difficult thing to do. We did have every individual marked as a kitten with small collars and then we trade those out for something bigger and hopefully we are able to follow the individual as they leave the population and move from where they’re born to potentially some place new where they establish and breed.

But as they move out at a greater distance then we’re limited because we’re flying for that radio signal. And it’s not always easy to keep up your circumference, and area that you have to cover gets bigger and bigger and your likelihood of being able to hit that signal gets more and more difficult. So we did, at the very end of the study, actually place some GPS callers on a few individuals. And that provided some really interesting information, although it was, you know, somewhat limited, because we didn’t have that many cats marked with GPS callers overall.

Julie: So you were referring to radio telemetry callers before then? Is that what they’re called?

Toni: Yeah.

Julie: Okay.

Toni: Yeah they’re a VHF — a very high frequency — radio collar. So it’s just a single signal that sends out, transmits, at a pulse rate that’s usually around 60 beats per minute, that when you go up and you plug in that animal’s frequency you can hear that particular pulse and locate the animal. Versus a GPS collar, which the type that we had actually transmitted the location of the cat through satellites to a computer system. And with those we got more locations and could document the actual travel route on almost a daily basis of where the cat was going, over a period of time. With our VHF…

Julie: It seems like that information could really help different states develop good management practices.

Toni: Oh absolutely, you know one of the things we’re interested in is what kind of habitats are these individuals moving through once they leave an area and there’re some other studies who’ve more recently employed this the same technique now using the GPS satellite system.

So gaining more information about where exactly these individuals are traveling and what happens to them over time, we still don’t always capture that but certainly some better information. And this enables us to actually look at not only where do these individuals end up and potentially establish so that we can maintain gene flow, but how do they get there and what are their potential barriers to movement?

Such as maybe highways or urban areas. And what are the areas that they successfully move through that maybe are potentially slated for some sort of development where we can inform, better inform, developers or participate in the discussion about how to alter that development that maintains some sort of linkage or corridor of movement.

Julie: Yes, and sometimes these dispersing juveniles wonder into towns, and there are encounters with humans or wildlife. What are some of the best practices that you can tell us about as far as nonlethal management of cougars is concerned, so that maybe, instead of killing a young cougar that comes into town, other strategies are being implemented?

Toni: Yes, that’s a really good question, Julie. Certainly during their dispersal, there’s just this huge motivation for these animals to move, which means that they often cross either rivers and highways more readily than generally adults do who are established in an area. And sometimes they’re killed because they may end up either killed on roads or by firearms in urban areas.

Recently in California, there’s been some, a study, that documented some of the cats die from exposure to anti-coagulant rodenticides. And these, some of these roads and certainly urban areas do function as barriers to movement where cats can kind of just end up in this spot, and not necessarily be able to figure out always a quick route out. Often they do. It is a concern when you have a cat hanging around an urban area for human safety. Certainly from the state management standpoint and by people who live in an area.

So some of the potentials are because those animals are dispersers, they’re actually already in a natural movement state trying to get to an area to establish on their own, and they tend to be pretty good candidates for translocation. They adapt quickly in or near release sites.

In a study that was done by me in New Mexico, Evaluating Mountain Lion Translocation, when we translocated a couple of individual cougars, those ones that were already in that dispersal age, you know, about 15 to 24 or 25 months old, establish very quickly. And they, a few of those actually ended up breeding in or near the areas where they released. Translocation is typically less effective for adults because they’ve been resident in an area so they often try to get back to that particular site. So.

Julie: So is that something state commissions look at — the age of the cat — before deciding its fate or if translocation might be something that would work?

Toni: Yeah, I think they look at that but beyond that, you know, there’s certainly some areas of concern and caution I think from state agencies and always employing translocation. One of those is statute of liability to a state agency, so if they move a cat and release it somewhere and it does end up getting back in trouble or coming into conflict with people then there’s potentially liability to the state agency. That’s one concern they have.

One of the other things that just is an area of caution is, you know, considering the transmission of diseases between populations, if you’re moving a cat a great distance. And that’s something that could be addressed through some sort of you know immunization or a checking quarantine type of protocol.

And then, also, just a consideration is potentially needing to genetically sample each of those individuals before they’re released because one of the things many of the states are trying to potentially embark upon, or there’s been a discussion at some of the last mountain lion workshops, is the use of DNA in monitoring populations.

So DNA from harvested individuals or those that may be handled by states for some reason or another, and starting to build a genetic database across large regions so we can better understand where individuals are moving from and to through DNA analysis. And so that should be another consideration when translocations might be employed.

Julie: So does that mean you’d actually purposely try to diversify the gene pool if you saw that looking at this one area it might not be beneficial to put a cougar back in that area because the gene pool wouldn’t be diverse?

Toni: Well, I think it’s more, you know, that’s maybe a potential area we end up in down the road — hopefully not in the west — but more from the perspective of you are now manipulating a gene flow from a translocation standpoint. So, you just want to have that, the information on that individual, knowing where it came from and where you’ve moved it to, to better understand if we’re employing this DNA technique on how that fits in to just the natural flow of the population’s…

Julie: Okay.

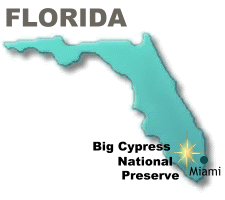

Toni: …gene flow between populations. But since you brought that up, you know the one place that this has actually occurred and it was — where translocation has been used to stimulate gene flow that was lost and to enhance genetic diversity — is with the Florida panther where they did move about ten I think, cats from south Texas into Florida. And released those for breeding purposes and to enhance the genetic diversity of that population. So there, it was used for that specific purpose.

Julie: Yes. And, one of my interviews was with Deborah Jansen with Big Cyprus National Preserve who was able to speak to that. And that was an interesting conversation.

Well, let’s jump back for a minute, because you were talking about a liability that agencies have with translocation if it doesn’t work. How is that tracked? Are there some things that are being done that could ensure that cougars might not come back into towns? For example, I’ve heard about some success using dogs, using hounds to chase them like Karelian Bear Dogs if I’m pronouncing the name of that breed correctly are sometimes used. What do you know about that?

Toni: Yes, well I do know like you that Karelian Bear Dogs have been used fairly successfully with teaching bears to try to stay away from people that it’s not a good thing to be in and around humans. And I think that my understanding from a talk I heard years ago now is that they’ve been using aversive conditioning with dogs, just regular hounds, not specifically Karelian Bear dogs, with some Florida panthers that have come in and around, and I think with some success. (Read an MLF opinion article about the hard release of a captured mountain lion using Karelian Bear Dogs, and recent news article about a dog injured on duty.)

I don’t think that the aversive conditioning with hounds has been used a lot by state agencies. So I don’t think there’s a lot of information on that yet but it seems that there is some potential to at least investigate that more. Particularly when you’re moving a cat through translocation and releasing it somewhere, just that little extra boost of chasing it and maybe putting it up a tree and doing that several times: giving it a bad experience.

Like any animal, food can be a huge motivation, so I think along with any type of translocation and also aversive conditioning, there should be a pretty good educational component with the people in both areas where the cat’s been moved from potentially to where it’s being released in terms of, you know, attracting prey into their yards.

With bears it’s putting out bird seed or other attractants because food is a huge motivation for animals. Particularly when they’re dispersing and they don’t know the landscape well, they’re looking for a new area to settle and often they encounter, you know, maybe it’s sheep or livestock, and those animals are pretty easy to capture and cats pick up on that pretty quickly. So, again, I think that education in terms of trying to reduce attractants in your yard that may bring these animals in is a good idea also.

Julie: That’s right. And we were mentioning science informing management earlier in the conversation. Do you know, are some states setting good examples that you could mention? As far as really letting the science lead?

Toni: Yeah, I think, I think Wyoming has recently developed a state management plan that certainly incorporates the science that has developed within their state into that management plan. Montana is another state that actually is at a point where they’re looking at redoing their state management plan. And they’re receiving a lot of pressure, as they always have in that state, from the houndsmen groups to do so.

And I’ve been involved with a couple of those houndsmen groups who are pushing exactly for that- – for having the science incorporated into the state management plan. They’ve also been at the forefront of trying to get not only me, but other scientists up to give public talks and involve the state biologists and commission when those presentations are given. So, often the incentive or pressure can come from the constituency that’s actually most involved on the ground which is the houndsmen.

Julie: That’s very interesting, and encouraging.

Toni: Yes, yes, I think it has been. I’ve enjoyed working with those groups. And it is refreshing to see that they do care about what’s going on. They’re out there everyday. And they may have different ideas about how to get to a certain point, but they’re all interested in preserving the culture of being able to hunt with hounds, but realizing that how a population functions is very important.

So, at least with Montana a lot of the pressure from the houndsmen is to have more conservative harvests of females. And in some areas they’ve pressured for actually a type of permit system. And not everybody agrees that that’s the best approach, but again, they’re highly involved with making sure every year that they’re having their input to the commission — how they think things should be done and with information from research studies. So they pay attention.

And I think Washington also has been doing a pretty good job. They recently completed a study involving houndsmen to try to collect DNA samples. So, prior to a hunting season, they had houndsmen work for them, to tree cats and use what is called a biopsy dart, to get DNA samples. And during the hunting season those were the returns, and with that information it’s kind of like a mark recapture setup study. They’re able to formulate a population estimate with those numbers. And, so, there again it’s using the resource to gain more information, and incorporating that information into their state management.

Julie: Well, we’re about out of time, but maybe I can conclude, well really with, with two questions. I just want to know what is it about cats? [laugh] What is it about cats that we love so much? Why care?

Toni: Well, you know, I think, there is… they give us this sense of wildness, and there’s still a mysteriousness about them for many of us. You know, we don’t get to see them very often. But it’s exciting to know that they’re out there: this sleek, amazing animal that I often call the Clark Kent of the mammal world — particularly the carnivore world — because they really have this meek and mild type of nature.

They move across the landscape very quietly; you rarely get to see them. And then they can turn into Superman when they need to feed themselves, taking down solitarily — by themselves — prey that could be five to seven times their body size. And I think that’s pretty amazing. And just knowing that they’re out there, and a part of the wildness that we all, I think are drawn to and like to experience, is exciting; at least for me, that’s certainly what draws me to them.

Julie: Yes, yes, I remember being really inspired reading a story about a family who lived close to maybe a national park, or some sort of greenbelt or large track of land, and there’s a mother cougar who would raise her young and use the stream bed and would frequently pass between homes. I don’t know how many in the small community, but the mother writing the article describes it, everyone in the community knew about the cougar and her kittens.

The children knew about them. There was respect in that they kept their distance. They kind of knew the route the mother cougar would take. People knew to put their animals in at night. And there really does seem to be this benefit, this win-win that there really maybe can be this balance and living close to nature, but with some good judgment and education, you can be both safe and really enjoy the benefits that living near wildlife brings.

Toni: Yeah, I think you’re absolutely right, Julie. You know, one of the things I like to talk to folks about is just how we tend to assess risk. And it’s usually what we know, we put low risk on. Things that we’re comfortable with like getting in a car everyday. I don’t think many people put a high risk on that. You feel pretty comfortable getting in your car and driving off to go somewhere. And yet auto accidents, I guess since 1975 average about 40 to 50 thousand deaths per year. And when you think about that, it’s a pretty significant risk to get in your car.

Yet being in and around cats there’s a very, very low risk. Cougar deaths since the 1970’s have been only one to two per year, actually less than that! So you know, I tell people I feel so comfortable when I’m out walking around and enjoying myself outdoors, but if you took me and put me in a big city, my view of risk just walking around people would go up hugely. And that’s not to say risk is greater, it’s just that’s my view, my perception of risk would be higher. You should be aware of your surroundings but cats really pose a very, very low risk.

Julie: Right, and I was gonna say, I get this image of you out there in Yellowstone, tracking through snow and studying cougars: you’re just another carnivore out there! [laugh]. You’re the human carnivore in the mix, [laugh].

Toni: You’re right, you’re right and that is true, [laugh].

Julie: Well, you contributed several chapters to the book Cougar Ecology and Conservation by Maurice Hornocker, pioneer and leader in mountain lion research. And I understand this book is a 2010 recipient of the Wildlife Publications Award?

Toni: Yes it is.

Julie: In the edited book category. Congratulations.

Toni: Yes, thank you. It’s very exciting and I think Maurice and Sharon did a wonderful job pulling together the individuals who contributed to the book and in editing the book. So yeah, we’re all pretty excited about the award which will be presented at the Wildlife Society Meetings on October 3rd of this year.

Julie: Fantastic, and your chapters, what, you’ve contributed 3 chapters to that book?

Toni: Yes, that’s correct. They’re all centered around cougar-prey relationships, cougar diet and then interactions with other animals, carnivores, for access to those prey.

Julie: Okay. Well, what’s next for your research in Yellowstone? Certainly you’ll continue to study carnivore interactions but are you working on a particular project now you’re excited about?

Toni: Yeah actually my study in Yellowstone wrapped up. They don’t go on forever, unfortunately. And you know, the after effects of that data collection is that we need to analyze it and get it out. Not just in scientific journals, but share the information in many different venues.

And I have recently completed a couple journal articles but am working on a larger project which is a book that will be co-authored by myself as senior author, Polly Beyott who’s worked for me for quite awhile, and also Maurice Hornocker. And it will be about cougars in Yellowstone, their ecology and interactions with other carnivores. So we’re looking to get that book wrapped up within the next year.

Julie: Well very good. I look very forward to reading that book. Well Toni Ruth, it’s a pleasure.

Toni: Well thank you, Julie.

Julie: Yeah, now keep doing what you’re doing, we appreciate it.

Toni: [laugh] Well thank you and I, we appreciate what you do too. And at anytime I can contribute with the education end of things I’m more than happy to do so.

Julie: Oh, very good. Well thank you have a good night.

Toni: Alright. You too.

Julie: Alright, bye, bye.

Toni: Bye bye.

Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for noncommercial use.

Mountain lion scat tends to be segmented with a diameter of an inch or larger. It often contains hair and bits of bone which may give it a white coloration. Mountain lions deposit their scat in prominent locations such as the middle of trails and dirt roads, along ridgelines, and near kill caches as territorial markings. This behavior is more commonly seen with males than females.

Mountain lion scat tends to be segmented with a diameter of an inch or larger. It often contains hair and bits of bone which may give it a white coloration. Mountain lions deposit their scat in prominent locations such as the middle of trails and dirt roads, along ridgelines, and near kill caches as territorial markings. This behavior is more commonly seen with males than females. As these scent markers are used for communication, a female ready for breeding that comes across a male’s scratch pile may also urinate on it to indicate she is in the area and looking to mate. Females with cubs are not looking to breed, and researchers often found the scat of these cougars covered within scratch mounds – a pile of one or more scats buried in leaves and soil – near a kill site. Her kittens commonly also left their scat in this “toilet.” Burying the scat might be a way to hide her scent and avoid attracting unwanted males who might harm her kittens. Males have been known to kill even their own

As these scent markers are used for communication, a female ready for breeding that comes across a male’s scratch pile may also urinate on it to indicate she is in the area and looking to mate. Females with cubs are not looking to breed, and researchers often found the scat of these cougars covered within scratch mounds – a pile of one or more scats buried in leaves and soil – near a kill site. Her kittens commonly also left their scat in this “toilet.” Burying the scat might be a way to hide her scent and avoid attracting unwanted males who might harm her kittens. Males have been known to kill even their own