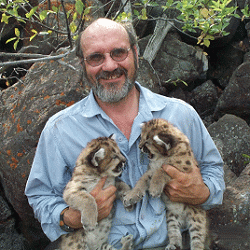

On Air with Tiger Expert Dr. Ullas Karanth

An Audio Interview with Julie West, MLF Broadcaster

Listen Now!

Listen Now!

Listen to the interview from MLF’s ON AIR program, podcasting research and policy discussions about the issues that face the American lion.

Transcript of Interview

Intro: (music) Welcome to On Air with the Mountain Lion Foundation, broadcasting research and policy discussions to understand the issues that face the American lion.

Julie: Hello. I’m Julie West, your host for OnAir. If you are tuning into this program and you support the Mountain Lion Foundation in other ways, you do so because you care about protecting North America’s big cat, the cougar. Our program today introduces the high stakes conservation challenges and successes impacting another majestic member of the big cat family: the endangered Bengal tiger, whose survival is threatened by large scale poaching, competition for resources, and diminished habitat and prey from human encroachment.

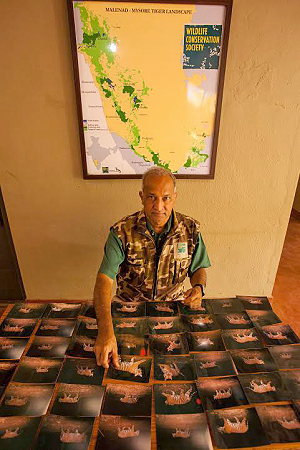

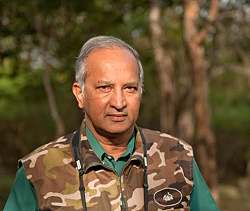

Join me as we travel to India to speak with Dr. Ullas Karanth, leading tiger expert and Director for Science Asia with the Wildlife Conservation Society. Dr. Karanth has conducted important longitudinal research on tiger ecology and other predators, pioneered camera-trap and radio-collar technologies, modeled wildlife populations, and advised conservation policy. He has published over 100 scientific papers and several books including The Way of the Tiger and Science of Saving Tigers. Tiger populations, in dire straits across India, have nevertheless revived in Nagarahole National Park and other protected areas across southern India and the Western Ghats of Karnataka thanks in no small measure to his passionate research. You can learn more about Dr. Karanth by visiting wcsindia.org.

Please give a warm welcome. I am with Dr. Karanth now. Greetings. Hello, Dr. Karanth.

Dr. Karanth: Thank you very much, Julie.

Julie: Yes, hello. Well, let’s start broadly. The tiger needs an enormous range with access to a sufficient prey base to sustain itself, yet India is developing rapidly, and its habitat is dwindling. What are the variables needed for tigers to thrive, and what are the key factors threatening their well-being?

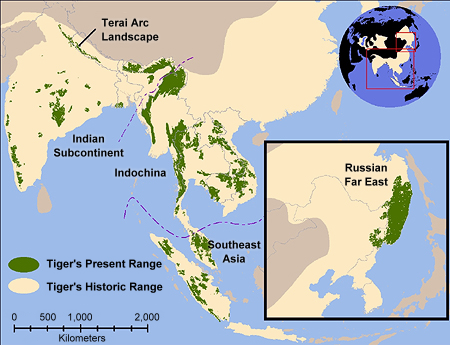

Dr. Karanth: To answer your first question. If you look at the distribution of tigers across their entire range, it has shrunk by 93 percent in the last two hundred years. That’s the grim view. The positive view is there is still a million square kilometers of tiger habitat left in the world where potentially tiger numbers could come back. And India alone has about 300 thousand square kilometers, or say, 250,000 square kilometers of tiger habitat potentially recoverable.

So that means, although the situation is grim now, if we do the right things, India could potentially hold 10 to 15,000 tigers, not just 2000 or something like that right now. So I view it, in a sense, as us doing the right thing rather than sitting back and wringing our hands and saying the tiger is doomed.

Julie: Nice, I like that — the hope side. And what about the key factors threatening their well-being.

But right now in the last 100 years or so in or within the remaining tiger habitat — because a century ago onwards we have started earmarking areas that won’t be converted to agriculture, so that will remain forest — now within this large area, which is about a million square kilometers now, the biggest threat has been hunting of the tiger’s food, that is deer, wild pig, wild cattle . . . the big hoofed animals that the tiger needs. Hunting of it by local people has been the big driver.

The biggest long-term challenge is the tiger habitats of human settlements in India. These are villages that are slowing growing into towns. People’s aspirations are changing. They want highways. So if we don’t have a strong policy to incentivize people to move away from these larger landscapes, or at least from the critical landscapes, that constitutes a threat.

Then, in the last 30 years or so, the rising affluence of China and other far eastern countries and the traditional belief — at one time affordable only by the super rich that tigers’ body parts have some medicinal or other sorts of values — that has driven direct killing of tigers big time. So these three sets have come in different stages. Right now I think the killing of prey species and direct hunting of tigers where there are reasonable numbers of them left, constitute the two big threats.

Another threat that looms large is that Asia is growing very rapidly. Countries like India and China are growing at the rate of six percent annually, and they support a quarter of the world’s human populations. So in the long run, developmental projects like infrastructure, highways, dams . . . these also loom as threats. They’re also beginning to impact tigers. So we need to prioritize our problems.

We are very clear that you cannot stop development everywhere, so we have to earmark high priority areas — at least five to 10 percent of the country and protect that. Then there are other conservationists who are very confused, who agree with the fact that industry and the infrastructure do damage and fighting those, but when it comes to abuse of the land or misuse of the land by local people and overgrazing of cattle or hunting by local people . . . they are deafeningly silent.

So there are a lot of them who make the noise only against the industrial development but are absolutely silent about the damage from local hunting, cattle grazing, forest fires, illegal encroachment that are not driven by big industry but driven by local forces. I think the fight has to be uncompromising. It has to be against both types of pressures. I consider only such people as true conservationists.

Julie: Ullas, tell us about the Wildlife Conservation Society and why it is an important hub for tiger conservation.

Dr. Karanth: Wildlife Conservation Society is over 100 years old. It’s based in New York. It runs the Bronx Zoo and other zoos, but it’s got this international side that very few people know about because we don’t publicize ourselves too much. But we work in 50 or 60 different countries. And we have major programs in India, Thailand, Russia, Malaysia and Burma working on tigers. And this program has played a key role.

Most of the big tiger biologists who are in the world today, tiger conservationists, have been a part of this program — either in the past or continue to be. So WCS is unique in the sense that all of the solutions are science based. We don’t create things top down. We do the science bottom up and say the animals need this. This is what the tiger needs, and we build solutions around that.

Secondly we are very strongly locally rooted. We don’t export solutions from New York to these situations. Our country program directors are all very strong, charismatic people from those countries who have their deep social feel for the context. And they’re able to deliver solutions by working with government as well as local people. So it’s kind of combining science with implementation.

We are working very intensively with local communities. We are doing proper analysis of where the tigers are, where the meta-populations are, and then we are going in there and talking to these remote communities who are in some of the prime tiger habitats in the long run, which will get ripped apart if these communities are developed by delivering them power and roads or whatever, and we are convincing them to accept relocation packages that are available and incentivizing them to move out.

We have worked on this for two decades and succeeded in convincing nearly one thousand families to move out of some of these key areas so that the tiger habitat becomes free, better connected and there is less conflict, less opportunities for hunting. This is one powerful approach that solves multiple problems at one shot. And we have been working very hard at it, and this involves working as much with local communities as with the governments.

Julie: Does the economic security of villagers affect wildlife conservation?

Dr. Karanth: Yeah, absolutely. There are a number of things here, but first question is if people are landlocked within prime tiger habitat, then conflict is inevitable, killing of tigers is inevitable and occasionally killing of humans by tigers becomes inevitable, so the solution is to improve their livelihoods and improve their economic security but not where they are — but maybe 10 miles away or 20 miles away, and this is extremely doable. And this is the approach we have taken.

The second set of issues is on the edge of the protected areas. This is where, I could even say surplus tigers spill over and sometimes cause conflict. So there you have to have measures for protecting livestock and compensating people when there are losses . . . it’s a different set of issues. But certainly economic issues affecting the farmers are a critical part of the solution to the larger crisis of the tiger.

Dr. Karanth: Yeah, absolutely. We act as advocates of these people. We go to not just government officials, to local religious leaders, local political leaders, the entire society . . . bringing their plight and the solutions to their attention so proper solutions are developed. For example, one of the beneficiaries of our relocation efforts has been a tribal young leader. And he is now so articulate that the government has put him on the National Tiger Conservation Authority as a member.

So we are very proud of actually supporting local communities in the right way and solving their problems rather than — as some conservationists do — condemning them to this existence of perpetual conflict with tigers in the middle of nowhere. So we are very proud of this approach.

Julie: Right. No, it really does seem like the Wildlife Conservation Society is an important hub connecting so many groups of people — wildlife scientists like yourself, you mentioned forest park officials, tribal people, NGOs, villagers . . . It must be quite a process of negotiation. Do you find that process to be challenging?

Dr. Karanth: Yeah, it is challenging. I have been involved in it for 26 years. And it’s been like running a marathon for 26 years. The marathon is also 26 miles long. So it’s not easy. One has to sacrifice some of the immediate scientific accomplishments to make time for all these other interactions.

But it’s not me alone.

Let me be very, very clear. It’s a group of local conservationists from small towns in Karnataka who were initially involved with me as volunteers in my field projects and today they are the stalwarts who are delivering these solutions. There is Girish who is a coffee planter. There is Muthannah who used to be a journalist. There is Vinay, who used to be a government official. There is Samba who used to be a management consultant. So all these guys have gravitated, settled down and built a strong non-governmental presence that works with the people. So in a sense I give them ideas and they implement it.

Julie: Let me ask about efforts that I know have been made and are being made to link lands considered to be important migratory corridors. How well connected are existing, protected tiger reserves, and are you involved in expanding these efforts?

Dr. Karanth: There are a few reserves such as Ranthambore, which are out on the western extremity of the tiger range, which kind of stand out with poor connectivity. But if you look at the large tiger landscapes of India — that is the Western Ghats, the central India forests, the deciduous forests, then again in the strip called Terai in northern India at the foot of the Himalayan Hills . . . these are pretty well connected.

India has had a good tradition of conservation compared to any other country in Asia. But we seem to be in the last ten years really abandoning it and going for the old model of growth for growth sake without caring much for nature.

Julie: Tell me, India’s Minister of Environment and Forests, Veerappa Moily, seems to be batting for industry more than for the environment. I know he’s controversially cleared an unprecedented number of high impact mining and manufacturing projects that would severely affect elephant corridors and tribal rights in addition to critical tiger habitat, so how does WCS address these kinds of decisions.

Dr. Karanth: See, we have to remember — although there is a lot of publicity suddenly being given — this process of giving environmental clearances and batting for the industry as opposed to nature did not start with Mr. Veerappa Moily. It’s been going on from the time — I would say at least 10 to 15 years ago and at least the last four or five environment ministers, have basically, if you look at the statistics, gone on clearing projects.

In some cases, a pile of them got stymied by courts, legal battles, etc. So the present minister represents a continuum. He’s not something unique, and it’s not as though before him there were people who were very friendly to the environment. The only political leader in India who had a real concern for conservation who put in very strong laws was Mrs. Indira Gandhi. And these laws were put in in the early 1970’s and then again another spell in the early 1980’s — the two times that she was in power.

And ever since then, any party, all politicians, have been trying to dismantle the strong nature conservation laws that she put in. The Congress party guys who succeeded her praise her and her greenness yet continue to do the same dismantling, whereas the opposition party guys don’t even see that. So I don’t see this getting any better. It will only get worse. This is what I see.

Julie: Now what about the role of the National Tiger Conservation Authority, Ullas?

Dr. Karanth: National Tiger Conservation Authority was set up in 2005. Its predecessor was a small compact committee called the Steering Committee of Project Tiger. I’ve been a member of that at times, and I’ve been a member of this Authority, and I think Authority is too big. It is too inflated; it is too bureaucratic. And in fact I think the old steering committee approach was a better approach then this bureaucratic set up that’s been set up. This is my personal view after being a participant in both things.

Julie: I see. Are they the ones who come up with something called the Tiger Conservation Plan?

Dr. Karanth: No, the Tiger Conservation Plans . . . there is a guideline given by the National Tiger Conservation Authority . . . it’s kind of a template. And the state government, park managers who actually manage the land come up with the plans according to that template. But the problem is the template is so inflated, has so many loopholes. If you won’t believe it . . . the management template itself is a 150 pages. So these management plans look like a New York telephone directory.

There are hundreds of pages of it, and a lot of it is completely unscientific. A lot of it emphasizes needless management and manipulation of vegetation. It’s very sad, actually. With all the good will in the world, we can’t produce a 10 page or 15 page or 20 page decisive management plan based on science for a tiger reserve after creation of the Authority five years ago.

Julie: Yes, so how do you get government leaders on board with the science, then? And maybe this is a good segue to also ask you to explain more about your camera trap technology and what we can learn about tigers from data gathered from these traps?

Dr. Karanth: One of the things is . . . for a long time there was no research on tigers. And in recent times . . . I began my work with tigers in 1988, and until 2005, there was very little research on tigers. Suddenly, you know after the crisis in Sariska where a whole . . . tigers went extinct in a park using an obsolete method called the pugmark census; they were still saying there are tigers. That’s when the task force was constituted by the prime minister, which said that ‘You should have more research.’

So now they are throwing a lot of money at research and monitoring. I’m not sure how much of it is good research because there is very little coming out by the way of high quality publications anywhere from all this money that’s being spent, but at least it’s better than the earlier days when there was absolutely no research and, in fact, an attempt to keep out researchers. That has changed. So I’m hoping, in future, that better research will feed into better management, but that needs a whole change in the management culture of generally respecting science and scientists, which still isn’t there.

Julie: And your camera trap technology . . . does that help with a census of tigers . . . that they identify?

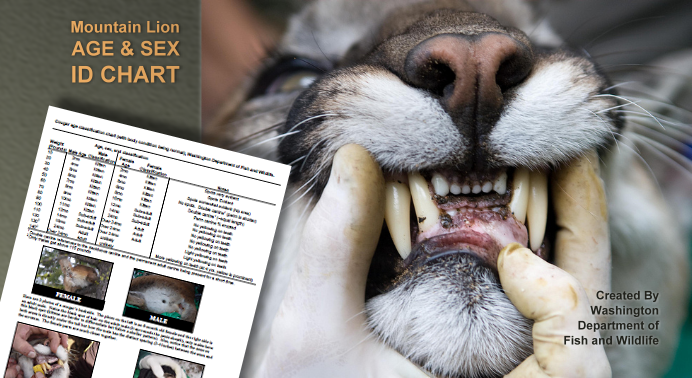

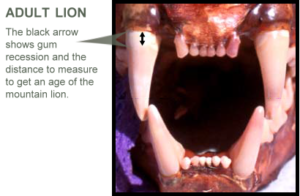

Dr. Karanth: Yeah, absolutely. See, if you have tiger populations that are vulnerable, small, scattered . . . their position is like they are patients in an intensive care unit in a hospital. So you need to monitor them really, really closely — how many are there each year, and how many are added to the population each year, and how many are lost from the population each year? These are all very, very difficult things to estimate for an elusive species like the tiger, which you don’t see, which hunts at night and avoids people. How do you get this information? And the camera trap has been a brilliant tool for doing that.

Because once you are able to get these pictures and identify individuals, all the complex statistical models that allow us to estimate growth rates, death rates, birth rates, recruitment . . . all these complicated mathematical statistical models can be applied once you have the power to identify individuals and monitor them over longer periods.

And the camera trap techniques does that. It allows you to unobtrusively enter the world of the tiger, get their pictures, get them ID’d, give them numbers. In my study now we have identified over 750 tigers in this landscape over the last couple of decades. And it’s fantastic data because you don’t have to catch the animal. You don’t have to chase the animal, track it, or any one of those expensive things like radio telemetry. It is simply placing some cameras in the habitat, but using some smart models, not just cameras. The statistics is equally important.

Julie: Yes, important tools indeed. Ecotourism has been described as being a double-edged sword for conservation because on the one hand it educates and raises awareness of the issues, and on the other hand it involves the presence of humans, which in and of itself often contradicts conservation goals. So how does ecotourism impact tiger conservation, and what’s going on with ecotourism in the tiger reserves of India today?

Dr. Karanth: My view is that ecotourism is potentially an incredible ally of conservation. If done right, it can be of great help to tiger conservation because it does two things: One is, if it’s priced reasonably, it allows people who live next to tigers to actually see the tiger, see the habitat — that’s the inspirational part. That is how people start feeling pride in something; people start caring for tigers. So its role in education is very, very high for India, because India is an industrial, developed country.

It’s not like some countries in Africa where tourism revenue is the main revenue. That’s not important at all for India. What is important is to use the nature reserves to get local people to feel a sense of pride in the tigers or rhinos or elephants. That’s clearly its fundamental role.

Its secondary role, which I think is also equally important — because, the kind of educational tourism I talked about does not generate a lot of money. It generates good will for the tiger — There’s another kind of tourism, which is the high-end tourism, because India now has a growing middle class, tremendous affluence, so there’s a large market, a growing market for people who want a high-end experience of wildlife. This is the kind of expensive tourism you have in South African lodges and all that. That’s also coming up in India.

Now this is a double-edged sword. On the negative side: Number one, is that to recover tigers, sometimes activities of local people have to be curtailed, like cattle-grazing, firewood collection, entry into the forest . . . all sorts of things. Now when you do that, you build some resentment, and on top of it if you take super rich or very well-off people inside — illogical though it may seem because these people are not necessarily always impacting negatively — sometimes they do because their resorts draw water from parks and there are those issues — but basically it creates a feeling that we are kept out of the park from doing ordinary livelihood things because rich people have to go in.

This to me is quite dangerous, so the first type of tourism has to be there. Now the positive side of this high-end tourism is, if we phase it out of the tiger reserves and encourage farmers outside the tiger reserves to turn their lands over to this type of high-end tourism — this is sort of like what South Africa has done; they have big Kruger Park with access to middle class South Africans, and high-end lodges fringing it all round where people pay a lot more but get a better experience — this has led to actually expansion of wildlife habitat.

I think that the power of high-end tourism is to actually expand these tiger reserves, but unfortunately, the tourism industry has no vision. They just go on putting more pressure on the existing parks like you see in Ranthambore or Kanha or any of these areas. They are not working with local landowners to get land use change outside so that this high-end tourism can be outside and budget tourism can be inside, and that way we end up educating people and also expanding tiger habitat. But I think tourism has potential, provided it’s managed wisely. Right now, unfortunately, it’s not managed wisely.

Julie: And how many tiger reserves are there in India right now?

Dr. Karanth: Right now around 40 or 41. But tigers are found outside tiger reserves, also. It’s not that tiger reserves . . . there are good areas, which are not tiger reserves, where there are tigers, not many, but a few. And there are many tiger reserves, which don’t have tigers, which are actually in a very pathetic state. The laws that actually, effectively protect nature is the Wildlife Protection Act, and there are two kinds of areas — called wildlife sanctuaries and national parks. The tiger reserve is an overlapping label on those.

So in national parks and sanctuaries, there is stricter control against hunting, there is money earmarked for relocating people, there is zonation to keep out tourism . . . all these things are there in some reserves, well-managed reserves. Some of the bad ones don’t have any of this.

Julie: In what ways is tiger conservation similar, perhaps, to mountain lion conservation in terms of some of the issues at stake?

Dr. Karanth: I would say that in terms of issues at stake, conservation of leopards is very similar to the mountain lion situation. Leopards are about the same size; they also can live completely outside the protected areas. You can have thriving populations without having large national parks or sanctuaries where they will live off small prey, unlike tigers, which can’t live on small prey.

Leopards can live off feral dogs, white-tailed . . . animals smaller than the white-tailed deer . . . so I think there’s a lot of similarity between leopards and mountain lions. And we have seen a resurgence of leopard numbers in India — pretty substantial. Once the massive hunting that was widely prevalent was abolished, now leopard populations are doing very well, well outside protected areas, sometimes in complete farmlands. This requires a new approach for protecting livestock.

My student, Vidya Athreya, has been working on this for building more tolerance to the presence of leopards, and I think this is where a lot can be learned about mountain lions. I think there’s a very hostile attitude towards mountain lions in the U.S., whereas the typical Indian villager or the society has much more tolerance. If a leopard is there, people will not necessarily go after it ’til the last one is wiped out. They don’t do that, unless it starts eating cows or some problem erupts, but generally people ignore the fact that there are leopards, because they’re not causing any harm.

I think that . . . and particularly given that the U.S. is overrun with white-tailed deer in so many parts, there’s so much prey for these mountain lions. I think the society should develop more tolerance for mountain lions. I would say that is the biggest cross-cultural transmission that can take place.

Julie: The tiger figures so prominently in ancient Indian texts and folklore and customs. It’s a national symbol. It’s venerated as divine protector, noble warrior. Do these myths matter? Do these stories and rituals play a part . . . or can they play a part in persuading . . .

You just compare China and India and look at India’s wildlife abundance, despite more poverty, despite an equally large human population, despite all the challenges, India has so much wildlife . . . so much social tolerance for loss that still through modern conservation, compared to any other Asian country, perhaps more than any other country in the world. So that certainly is a critical part of why we have succeeded.

I still see India’s wildlife conservation story as a tremendous success in the last fifty years compared to whatever else that has gone on anywhere in Asia.

Julie: Beautiful. What do you consider to be one or two of your greatest accomplishments in championing the rights of tigers?

Dr. Karanth: I think in terms of science, the methods that I developed for studying tiger populations — they are widely used now, not just for tigers, jaguars, cheetahs, but for a variety of species. I am very happy that it took a long time, but it did yield a result that is applicable widely.

The second thing that I am somewhat pleased — I am 65, so at this age I am a little pleased — is that when I post for this solution of incentivizing people to move out of tiger habitats with the voluntary relocation model as the win-win solution in 1993, Wildlife Conservation Society pushed this idea. I was very strongly behind the idea. We were very highly criticized at that time. No other conservation NGO talked about it. Even now they are very gingerly talking about it. We went ahead, developed this idea, implemented this idea and showed that it worked. So I am really proud of that.

And the third thing I am proud of is that I grew up as a village boy in my landscape in Malnad region of Karnataka. And in this landscape when I was born, when I was a teenager 50 years ago, tigers were on the verge of extinction. They were almost gone. Forests were being wiped out. Through all this . . . it’s not just my effort. All the effort that has gone on . . . the credit for the recovery of wildlife from the 70’s to the 80’s is not . . . I had very little role.

At that time I was observing, growing, learning. So whatever I have done is post 1980’s. So that original recovery credit must go to the forest service, to Indira Gandhi, and to naturalists of my earlier generation. My contribution in all this has been that through my work, I have created a number of local conservation groups and conservation leaders who are playing such a vital role. So kind of mentoring them and growing them has been a very, very rich experience for me. So these two or three things are really important for me.

Julie: Well, final question, Dr. Karanth — what would you like to leave us in thinking on tigers? What is the prognosis for tigers in India? What would you like us to take away?

Dr. Karanth: I think India should have 10 to 15 thousand tigers in 20 years time, and the world should have about twenty-five to forty thousand tigers. I think it’s extremely doable. We have all the resources.

We have more capability now. We still have sufficient land. We just have to be smart, and we can have a world with forty thousand tigers.

Julie: Nice! Well, thank you so much for spending time with me today in this conversation. It was a pleasure!

Dr. Karanth: Thank you, Julie. Thank you for giving me an opportunity to talk to all the big cat fans in North America.

Julie: You’re welcome.

Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for noncommercial use. For more information visit mountainlion.org.

MARCH & RALLY DETAILS

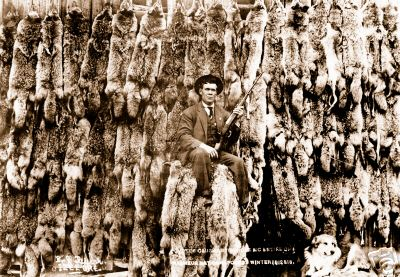

MARCH & RALLY DETAILS Lion cubs are hand reared at these murder farms, where unknowing volunteers habituate them to humans. When large enough, these lions are confined, often drugged, and killed by bullet or arrow in canned hunts. Their heads are imported to the US, Europe, and other countries and their bones sold to countries all over Asia for bogus “medicinal purposes.”

Lion cubs are hand reared at these murder farms, where unknowing volunteers habituate them to humans. When large enough, these lions are confined, often drugged, and killed by bullet or arrow in canned hunts. Their heads are imported to the US, Europe, and other countries and their bones sold to countries all over Asia for bogus “medicinal purposes.”

are often portrayed as having, are they not doing it just out of pure joy, bloodlust?

are often portrayed as having, are they not doing it just out of pure joy, bloodlust?

But, those game agencies continue to ignore the evidence, continue to pander to the irrational mob attitude of a small segment of society who is attempting to take away all that my generation has given. Attempting to again destroy species, ecosystems. We must stand up to these forces of ignorance and hatred and just say NO! The integrity of the ecosystems that support us depends on it.

But, those game agencies continue to ignore the evidence, continue to pander to the irrational mob attitude of a small segment of society who is attempting to take away all that my generation has given. Attempting to again destroy species, ecosystems. We must stand up to these forces of ignorance and hatred and just say NO! The integrity of the ecosystems that support us depends on it.

This killing of prairie dogs is ostensibly justified by some to rid the land of “vermin” or animals that conflict with say ranchers or farmers. Yet numerous studies have documented the importance of prairie dogs in supporting many other wildlife species from blackfooted ferret to burrowing owls.

This killing of prairie dogs is ostensibly justified by some to rid the land of “vermin” or animals that conflict with say ranchers or farmers. Yet numerous studies have documented the importance of prairie dogs in supporting many other wildlife species from blackfooted ferret to burrowing owls.

One increasingly popular idea is to remove management authority for predators from state wildlife agencies. Some suggest transferring it to other state agencies with less obvious conflict of interest such as environmental or park agencies.

One increasingly popular idea is to remove management authority for predators from state wildlife agencies. Some suggest transferring it to other state agencies with less obvious conflict of interest such as environmental or park agencies.