Florida FWC investigates disorder impacting panthers

The FWC is investigating a disorder detected in some Florida panthers and bobcats. All the affected animals have exhibited some degree of walking abnormally or difficulty coordinating their back legs.

As of August 2019, the FWC has confirmed neurological damage in one panther and one bobcat. Additionally, trail camera footage has captured eight panthers (mostly kittens) and one adult bobcat displaying varying degrees of this condition. Videos of affected cats were collected from multiple locations in Collier, Lee and Sarasota counties, and at least one panther photographed in Charlotte County could also have been affected. The FWC has been reviewing videos and photographs from other areas occupied by panthers but to date the condition appears to be localized as it is only documented in three general areas.

FWC asks public to help document disorder impacting panthers – YouTube

The FWC is testing for various potential toxins, including neurotoxic rodenticide (rat pesticide), as well as infectious diseases and nutritional deficiencies.

The public can help with this investigation by submitting trail camera footage or other videos that happen to capture animals that appear to have a problem with their rear legs. Files less than 10MB can be uploaded to our panther sighting webpage at MyFWC.com/PantherSightings. If you have larger files, please contact the FWC at Panther.Sightings@MyFWC.com.

For more information and FAQ’s regarding ongoing efforts to identify and manage the cause of this neurological disorder, visit: myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/panther/disorder/.

Bringing the Florida Panther Back from the Brink

In 1950, Puma concolor coryi’s status changed from a “nuisance species” to that of a game animal. This status change halted indiscriminate killing, but the Florida panther wasn’t really protected until 1958 when it was listed as a state endangered species, and then later when it attained federal listing as an endangered subspecies on March 11, 1967.

In order to consider delisting the Florida panther from the endangered species list, the federal recovery plan requires:

-

- Three viable, self-sustaining populations of at least 240 individuals (adults and subadults) each have been established and subsequently maintained for a minimum of twelve years.

- Sufficient habitat quality, quantity, and spatial configuration to support these populations is retained / protected or secured for the long-term.

- Exchange of individuals and gene flow among subpopulations must be natural (i.e., not manipulated or managed).

1988, seven wild mountain lions were caught in west Texas, sterilized to prevent breeding, and released into northern Florida to study the feasibility of relocating panthers.

The results from this study were used to design and implement a second study in February, 1993 to evaluate the use of captive-raised animals in reestablishing a panther population in northern Florida and southern Georgia. Nineteen mountain lions, including 6 raised in captivity and conditioned for release into the wild, were released into the northern Florida study area and monitored through June 1995 (Belden and McCown 1996). This study found that reestablishment of additional Florida panther populations was biologically feasible.

In 1995, in an effort to reverse the effects of inbreeding, eight young-adult, non-pregnant, female, Texas mountain lions were captured and introduced into the Florida panther population.

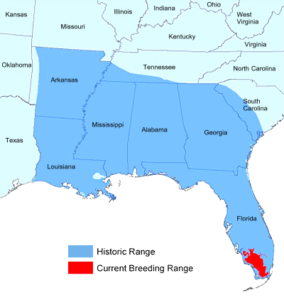

A 1996 status report on the Florida panther by the Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission noted that the only documented breeding population of Florida panthers remained in southern Florida from Lake Okeechobee southward, primarily in the Big Cypress and Everglades physiographic regions. At the time it was estimated that only 30 to 50 animals, living in an area of roughly 4,000+ square miles, still remained. The Commission’s analysis indicated that, “without intervention, the Florida panther population had a high probability of becoming extinct in 25 to 40 years.”

The report went on to state:

The Florida panther faces the threat of extinction on 3 fronts. First, there is continual loss of panther habitat through human development. This continuing decline in available habitat reduces the carrying capacity and, therefore, the numbers of panthers that can survive. Second, genetic variation is probably decaying at a rate that is causing inbreeding depression (reduction of viability and fecundity of offspring of breeding pairs that are closely related genetically) and precluding continued adaptive evolution (Seal and Lacy 1989). Third, panther numbers may already be so low that random fluctuations could lead to extinction.

Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission

1996 Florida Panther Status Report

Due to many factors, including the influx of new genetic material, increased public awareness, innovative wildlife corridors across deadly highways, and the acquisition of critical panther habitat within the primary zone, Florida’s panther population has, at the very least, doubled in size and stepped back from the brink of extinction. However, the inability of the species to expand beyond its tiny refuge in the Everglades will keep it on the endangered species list for a long time to come.

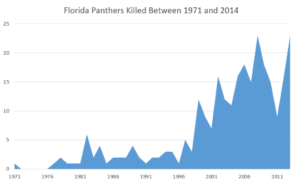

Human-Caused Mortalities in Florida

Now that the Florida panther is listed as a federally protected species, the number one cause of panther mortality in Florida is lack of sufficient habitat.

Florida’s crowded conditions force young panthers into situations where they have to fight older more experienced panthers to establish their territories, or if they do disperse, put them at risk of being killed in an automobile collision. The five-year average of annual panther mortalities is 25 per year, with, on average, 17 of those animals being killed by motorists.

After automobile accidents, intraspecific aggression is responsible for the next largest number of panther deaths.

Puma concolor is a species which, after dispersal, does not normally come into contact with other panthers except to breed, or on the part of females, raise their young.

Male panthers will fight and attempt to kill other panthers that enter established territories. Kittens are also at risk from male panthers since their deaths will allow their mothers to breed again. On average, intraspecific aggression is responsible for around 6 panther deaths per year, that we know of.

MOUNTAIN LION MORTALITIES IN FLORIDA

1990 – AUGUST 28, 2012

| Vehicular Trauma |

154 |

| Illegal Killing |

7 |

| Natural or Intraspecific Strife |

90 |

| Research |

1 |

| Unknown / Unspecified |

45 |

| Sport Hunting |

0 |

| Depredation |

0 |

| Public Safety |

0 |

| Wildlife Services |

0 |

Secondary Zone

Secondary Zone