Legal Status

- Classified as a game animal.

- Hunting is open year-round.

- Hunters are allowed to use dogs to hunt lions.

Estimated population: Nevada Department of Wildlife previously used a population estimate of 2000 mountain lions, but recently commissioned a third party to develop population reconstruction model using hunter harvest data. The model estimates the population at 3,400 mountain lions. However, the model likely overestimates the population both due to relying heavily on hunter harvest data (a nonrandom sampling source) and because no consideration of habitat conditions were factored into the model. Research from Nevada and the Great Basin demonstrates that megadrought conditions from human induced climate change are decreasing the abundance of both mountain lions and their prey.

Annual hunting: Nevada sets high annual quotas of around 250 lions

NDOW has been managing mountain lions a big game mammal since 1965. Nevada still uses the Comprehensive Mountain Lion Management Plan written in 1995. In that plan, the Nevada Department of Wildlife stated that its goals and objectives are to:

- maintain mountain lion distribution in reasonable densities throughout the state;

- control mountain lions creating a public safety hazard or causing property damage;

- provide recreational, educational and scientific use opportunities of the mountain lion resource;

- maintain a balance between mountain lions and their prey; and

- manage mountain lions as a meta-population.

Unfortunately, the plan has not done much to benefit lions and is merely a way to set annual hunting quotas and predator culling goals for specific game management areas.

A review of available documents found:

- There is no mention of mountain lions in the NDOW Comprehensive Strategic Plan 2004-2009 (the all-encompassing document that addresses how NDOW will protect the natural resources under their jurisdiction).

- Mountain lions are barely acknowledged as even existing within the 629 pages of the 2006 Nevada Wildlife Action Plan.

- Mountain lions are not included in the state’s 2013 Wildlife Action Plan, despite 46 pages being allocated for Nevada mammals.

- The 1995 Cougar Management Plan was still referred to as the State’s standard plan in a 2008 Mountain Lion Status Report.

- The only “plans” which reference mountain lions at all are the Nevada Predation Management Plans.

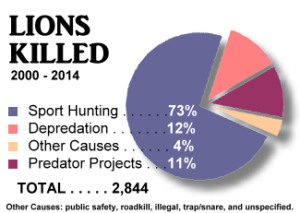

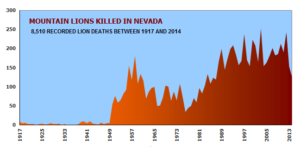

Human Caused Mountain Lion Mortalities in Nevada

Since 1917 (the first year records are available) until 2015, an estimated 8,510 mountain lions have been killed by humans in Nevada, with 80 percent of these deaths occurring after 1965 when mountain lions were classified as game animals.

This figure does not include:

- many of the lion deaths from road accidents

- secondary poisoning

- kittens or injured adults euthanized by NDOW

- death by unknown causes

- intraspecific strife from home range disruption

- poaching

- the “shoot-shovel-and-shut up” practices espoused by some ranchers

Hunting Mountain Lions in Nevada

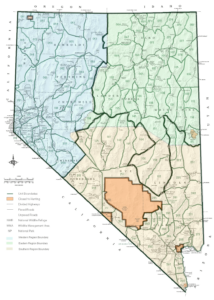

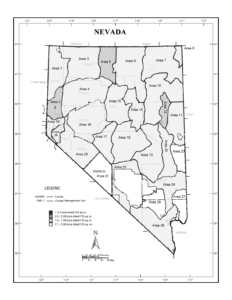

Nevada’s Mountain Lion Hunting Season runs all year, from March 1 through February 28. Night hunting is also allowed. Nevada’s 17 Game Management Units (GMUs) are combined into three hunting regions (Western, Eastern, and Southern). Hunting quotas are established for each of these regions rather than for individual GMUs.

When the quota (also called “harvest objective”) has been met for a given hunting region, the lion season is closed in that region. With this policy it is possible that some Game Management Units might experience greater lion mortality than others within the same hunting region.

Nevada’s 2022-2023 Lion Harvest Objectives 247 mountain lions.

In 2003, Nevada provided a gender breakdown of its mountain lion harvests for the years 1998 through 2001. During this 4-year period 41 percent (282) of the total human-caused mountain lion mortalities were female cougars.

According to MLF’s 11 western state study of human-caused mountain lion mortalities (1992-2001) the Nevada Game Management Units (GMUs) most responsible for mountain lion deaths were numbers 12, 11, 5, 6, and 2. From 1997 to 2001, these GMUs accounted for 285 human-caused mountain lion mortalities.

During this time period these GMUs were responsible for 29 percent of human-caused mountain lion mortalities while encompassing only 11 percent of Nevada’s mountain lion habitat. GMU-12 was ranked as Nevada’s number one killing field during the study period with an average mortality density rating of 1.5.

Politics and Mountain Lion/Predator Control Directives in Nevada

Decisions regarding mountain lions in Nevada appear to be increasingly dictated by politics rather than sound science. Greg Tanner, a wildlife biologist with the Nevada Department of Wildlife, is quoted in an April 12, 2004 High Country News article as saying that “Game commissions make decisions based on what they hear from their sportsmen constituents.”

This opinion of political manipulation of the Nevada Board of Wildlife Commission (NBWC) by hunting groups was reinforced on December 5, 2009 when the NBWC approved three projects sought by private sportsmen groups to kill the predators of mule deer and sage grouse — specifically mountain lions. This approval was made despite arguments against the plan presented by the Director of the Nevada Department of Wildlife.

In a March 9, 2010, Reno Gazette Journal news article Tony Wasley, a former NDOW mule deer specialist and current Director of NDOW, stated that controlling predators won’t stop the disappearance of the sagebrush-covered terrain that deer depend on in Nevada and much of the West. “We’re talking about a landscape-scale phenomenon here,” Wasley said. “The [Nevada deer] population is limited by habitat. Where there is insufficient habitat, all the predator control in the world won’t result in any benefit.” Unfortunately his argument, and those of fellow biologists, has not debunked the popular opinion of many hunters (that an exploding mountain lion population is eradicating Nevada’s deer herd) or those of their sympathetic lawmakers.

Also in March 2010 the implementation of the special mountain lion removal plan was put on hold when, citing lack of full support from Nevada officials, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services (WS) refused to carry it out. As a result of this refusal, the Nevada Board of Wildlife Commission created the Mule Deer Restoration Sub-Committee (now called the Mule Deer Working Group) with the stated purpose of helping to restore mule deer numbers in the state. There is some question as to the impartiality of this committee. At its second public meeting on April 15, 2010, committee liaisons with the Nevada Cattlemen’s Association, Nevada Farm Bureau, and Wildlife Services (the agency which carries out the state’s predator control directives) were announced.

Predator Management Program and the $3 Fee

AB291 Introduced at the 71st session of the Nevada State Legislature on March 6, 2001 sought to establish a fee for all Nevada hunt permit applications to be used for predator management. NRS 502.253 was signed into law May 31, 2001. This legislation created an additional application processing fee ($3) for all game tags to be used by NDOW for costs related to:

- Programs for the management and control of injurious predatory wildlife;

- Wildlife management activities relating to the protection of nonpredatory game animals, sensitive wildlife species and related wildlife habitat;

- Conducting research, as needed, to determine successful techniques for managing and controlling predatory wildlife, including studies necessary to ensure effective programs for the management and control of injurious predatory wildlife; and

- Programs for the education of the general public concerning the management and control of predatory wildlife.

According to Nevada’s Predator Management Plan FY 2022, there are 12 predator management projects totaling $749,000. Six of these projects involve lethal removal of mountain lions and amount to $430,000.

Project 22-01: Mountain Lion Removal to Protect California Bighorn Sheep (Unit 011 and 013) – $90,000

NDOW biologists, USDA Wildlife Services, and private contractors will

collaborate to identify current and future California bighorn sheep locations and determine the best methods to reduce California bighorn sheep mortality. Traps, snares, baits, call boxes, and hounds will be used to proactively capture mountain lions as they immigrate into the defined sensitive areas.

Project 22-074: Monitor Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep for Mountain Lion Predation (Unit 074) – $20,000

NDOW biologists will identify current and future Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep locations and determine the best methods to monitor this population. Additional GPS collars will be purchased and deployed to monitor the bighorn sheep population. If mountain lion predation is identified as an issue, then traps, snares, baits, call boxes, and hounds will be used to lethally remove mountain lions from the area.

Project 37: Big Game Protection-Mountain Lions (Statewide) – $100,000

NDOW will specify locations of mountain lions that may be influencing local

declines of sensitive game populations. Locations will be determined with GPS 16 collar points, trail cameras, and discovered mountain lion kill sites. Removal efforts will be implemented when indices levels are reached, these include low annual adult survival rates, poor fall young:female ratios, spring young:female ratios, and low adult female annual survival rates (table 3). Depending on the indices identified, standard to intermediate levels of monitoring will be implemented to determine the need for or effect of predator removal. These additional monitoring efforts may be conducted by NDOW employees, USDA Wildlife Services, or private contractors. Staff and biologists will identify species of interest, species to be removed,

measures and metrics, and metric thresholds. This information will be recorded on the Local Predator Removal Progress Form (see appendix) and included in the annual predator report.

Project 40: Coyote and Mountain Lion Removal to Complement Multi-faceted Management in Eureka County (Unit 144) – $100,000

USDA Wildlife Services and private contractors working under direction of

NDOW and Eureka County, will use foothold traps, snares, fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters for aerial gunning, and calling and gunning from the ground to remove coyotes in sensitive areas during certain times of the year.

Project 42: Assessing Mountain Lion Harvest in Nevada (Statewide) – $20,000

A private contractor will use existing mountain lion harvest data collected by NDOW biologists to develop a harvest model. The modeling approach will

involve Integrated Population Modeling (IPM) which brings together different sources of data to model wildlife population dynamics (Abadi et al. 2010, Fieberg et al. 2010). With IPM, generally a joint analysis is conducted in which population abundance is estimated from survey or other count data, and demographic parameters are estimated from data from marked individuals (Chandler and Clark 2014). Age-at-harvest data can be used in combination with other data, such as telemetry, mark-recapture, food availability, and home range size to allow for improved modeling of abundance and population dynamics relative to using harvest data alone (Fieberg et al. 2010). Depending on available data, the contractor will build a count-based or structured demographic model (Morris and Doak 2002) for mountain lions in Nevada. The model (s) will provide estimates of population growth, age and sex structure, and population abundance relative to different levels of harvest.

Project 44: Lethal Removal and Monitoring of Mountain Lions in Area 24 (Areas 23 and 24) – $100,000

Mountain lions in the area of concern will be lethally removed (see map) until three consecutive years of adult annual survival for bighorn sheep exceed an average of 90% and fall female to young ratios exceed 30:100.

Mountain lions in the proximity area (see map) will be captured with the use of hounds and/or foot snares. Captured mountain lions will be chemically immobilized and marked with a GPS collar. Marked mountain lions that enter the area of concern and consume bighorn sheep will be lethally removed.