Pen Build Instructional Video

This instructional video walks viewers through the process of assembling an easy-to-build secure enclosure to protect domestic animals from predation.

This instructional video walks viewers through the process of assembling an easy-to-build secure enclosure to protect domestic animals from predation.

Listen Now!

Listen Now!Listen to the interview from MLF’s ON AIR program, podcasting research and policy discussions about the issues that face the American lion.

Intro: (music) Welcome to On Air with the Mountain Lion Foundation, broadcasting research and policy discussions to understand the issues that face the American lion.

Julie: Hello. You are listening to On Air with the Mountain Lion Foundation. I’m Julie West, your host. My guest today is Phil Carter, wildlife campaign manager with Animal Protection of New Mexico, a non-profit organization that has been advocating the rights of animals since 1979. APNM tirelessly works to reverse the outmoded view that cougars are nuisance animals that should be eradicated, and it aims to counter these prejudices with a biocentric approach accomplished through education, outreach, and campaigns for the protection of and coexistence with wild species in New Mexico.

Phil coordinates campaigns on behalf of the organization and initiates collaboration with state officials and the general public to produce progressive change in New Mexico cougar management. To this end, he networks and communicates with land owners, other non-profit organizations, New Mexico department of Game and Fish, New Mexico Environment Department, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, New Mexico State Parks, tribes, and other agencies about human/animal conflicts and benefits.

So, welcome Phil. Hello.

Phil: Thanks for having me on.

Julie: Yes. Now, I understand that New Mexico is considered to be a premier site for cougar populations. What are the variables that make it so, and what significance does this hold for their survival?

Phil: Well, New Mexico certainly has a fairly robust population of mountain lions. They were never really hunted out here in this state. There’s always been kind of a background population. Again, the mountain terrain, relatively low population of the state — there’s only about 2 million New Mexicans — means there’s a lot of open space where these cougars can live and thrive.

Julie: What are the issues at stake for the cougar in New Mexico?

Phil: Certainly my organization, Animal Protection of New Mexico, has been working with the state wildlife agency, which is the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, for coming up on 15 years now, really kind of working with them to manage these cougars better, more scientifically.

We had a lot of really progressive changes in management in the last decade, around 2005-2006, which included development of a really thorough, complex habitat map, which is something the department never had, that in coordination with our organization we were able to produce something to really better manage the cougar population in each, what they call, game management unit around the state, of which there are dozens.

Also a change that we helped Game and Fish work on in cougar management was the institution of what’s called the Total Sustainable Mortality Limits for Cougar Management. What this does is it monitors total mortality of cougars, not just from harvest, which cougars are legal to hunt here in New Mexico, but also any sort of deaths of cougars from road kills, depredation, or other natural causes.

It really gives a much more clear picture about how many cougars, of this small population here in New Mexico, are dying off and when do game management units need to be closed or when does hunting need to be limited to make sure we have a robust and sustainable population of the cats.

Julie: What are the numbers that reflect that total sustainable mortality rate?

Phil: Basically New Mexico is the site of an extremely thorough study called – it was published as Desert Puma, by Dr. Logan and Dr. Sweanor, Ken Logan and Dr. Sweanor, who both work for Colorado Fish and Wildlife Department.

The numbers that they came up with from that 10 year study, that was paid for by New Mexico tax payers to the tune of about a million dollars, the conservative estimates of the total populations of cougars are around 2041 to 3043. So between 2000 and 3000 here in New Mexico.

Again, this is really just a premier cougar population study. I don’t know if anything that is more thorough that’s been done in any other state.

Julie: Your organization uses the Hornocker study.

Phil: Yes, definitely. It’s the opinion of a lot of us in the environmental community that ever since the Hornocker study was published around 2000-2001, the Game and Fish Department here in New Mexico have been giving a concerted effort to downplay it’s finding, which is disappointing as it was a taxpayer funded study, and it is such a great resource for wildlife managers here.

Julie: So the Hornocker study suggested that the population numbers were hovering right around 3000-3043, and what do the total sustainable mortality figures reflect in relation to that number?

Phil: It varies by game management units here in New Mexico. I don’t know of any game management unit under the more conservative estimates by the Hornocker study that are over 400 cougars. Again, that’s on the high end, and I should really just back up and say it’s really just 2000 to 3000 are the conservative estimates of the total population here in New Mexico.

Now, asking the Game and Fish Department, their biologists starting in 2010, they went to the extreme high end of what the Hornocker study prescribed and decided that they were going to consider total cougar population here in the state as between 3000 and 4200. That was the first indication that my organization and others was that something’s not quite right about such a drastic change in management in just one year.

Julie: How did those numbers, then, influence the hunting quotas on cougars?

Phil: In July, 2010, the Game and Fish Department issued its recommendations for the next round of what’s called the Bear and Cougar Rule here in New Mexico. This is what dictates management of both black bears and mountain lions here.

Where it was an annual quota, which is basically the hunting quota, how many cougars can be sustainably managed and hunted per year, where it was in 2009 at 490 cougars per year, it got bumped up, just in the span of one year, to 1109. Those were the new recommendations issued in July 2010 by Game and Fish Department. There was also a huge increase of the female sub-limits, which is basically the quota for hunting female cougars. Where it was 126, it became 386.

Julie: Right. That was approximately a 200 percent increase in their sub-quota. Considering females are considered to be the biological bank account, so to speak, of the population, they should require special care. Is it reasonable to suggest that these quotas could potentially eradicate the population?

Phil: Certainly, me and my colleagues in the environmental community made those suggestions heavily when those recommendations were released in July 2010. Through our efforts at working with state government, including the governor’s office, as well as mobilizing the public who was concerned about such a drastic increase, Game and Fish Department came back in late August, 2010, with a new number that shows 996 cougars per year.

Julie: So it had been 409. They proposed over 1110…

Phil: 490.

Julie: … and then there was a public outcry to reduce that number to whatever you said – 900 and some? And what is the current quota in 2012?

Phil: The current quota, because that new number, 996, didn’t satisfy me and my colleagues in the environmental community either. The reason for that being is a number of reasons was the Game and Fish Department was using, in our opinion, was essentially replacing the Hornocker Study with what was called the Perry Study. What this was a one-year study that was conducted as a Masters thesis here in New Mexico. A population survey on one small area.

At the time the Game and Fish Department was citing it as the main source of their population assumption for cougars in New Mexico, it had not been published, nor had it even been peer reviewed. It was only submitted as a Masters thesis. That kind of really set off some red flags amongst me and my colleagues.

So we filed what was basically the state version of a freedom of information act request here in New Mexico, which all three agencies are required to comply with within 2 weeks. One of our requests was can we see a copy of this Perry study, because as it wasn’t published or even mentioned in any scientific journal, we couldn’t get a copy of it.

Two weeks later, I get contacted by Game and Fish to come pick up the documents, and lo and behold, the Game and Fish Department office claimed they didn’t even have a copy of the study. What they were essentially using as a major basis of the population assumptions for cougars, they claimed to not even have a copy of it within their office.

Julie: How does something like that get through the cracks? You would think that they would be working very closely with wildlife biologists to get the latest numbers in order to better reflect policy. How did something like that happen? What was the reasoning?

Phil: Unfortunately, New Mexico state law is not like federal law. For the endangered species act, you’re required to use what’s called best available science. New Mexico has no such provision like that. So really the wildlife biologists in the employment of the state are kind of free to set their own determination to the best available science.

Ultimately they decided to largely base their population figures on what we considered a highly questionable study, which is not to downplay the value of the study itself. We later had to get a copy of it from Dr. Perry himself, because the state didn’t have a copy of it. But to base something as important as cougar population figures on a one-year study that had not received any peer review, nor was even published, we considered highly questionable.

Julie: So if wildlife biologists themselves were in a sense advocating for this document, using it as their baseline, it sounds like there must be some division within the wildlife biology community itself. Do the biologists sit down, convene at a table with everybody and hash these discrepancies out? Was there any kind of a meeting to really look closely at these figures?

Phil: I assume that the department biologists had met amongst themselves and decided to use this particular study, as well as a few others, to make these determinations. But certainly my organization, nor any of my fellow environmental organizations were not invited to the table that time.

For the endangered species act, you’re required to use what’s called best available science. New Mexico has no such provision like that.

Julie: So it’s encouraging then that the public actually lobbied on behalf of the mountain lion and in essence were responsible for the lowering of that initial number. What do you account for the public’s support of the mountain lion in New Mexico?

Phil: I think organizing on our part with APNM and other organizations and the fact that it was a kind of a shock to a lot of people to have essentially a 200 percent increase originally, I think really galvanized a lot of public opposition.

Julie: Especially if you were to take the high end. Even if you were to take the 4200 end of the Hornocker Study, or 3000, that 1000 figure is outrageous.

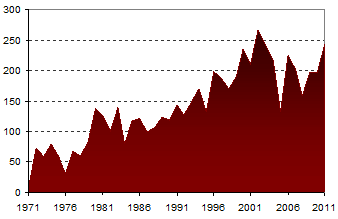

Phil: Right. It’s essentially they were claiming a quarter more cougars than what we considered under the precautionary principal that this has always been a relatively rare species and management really needs to reflect that. And then as you mentioned, ultimately in October, 2010, at the final vote the Game and Fish Department lowered the total quota further to about 742 cougars total. But there’s this kind of this pervasive sense of arbitrariness to all these numbers because really even under the original 490 number, hunters rarely got over 200 cougars per year. The fact was trying so outrageous increases on this when, even under the original quota, hunters were getting less than half of it per year, was really almost kind of surreal to watch play out like that.

Julie: So there’s an inflation between the actual harvest quota and the total projected quota.

Phil: Right. It’s very strange to watch play out because the Game and Fish biologists, as well as the Game commissioners are very aware that only a percentage of these hunting quotas are being met from year to year.

Julie: Then maybe can that suggest, potentially, a lower population than originally thought if consistently hunters can’t even bring in more than 200 a year? Does that mean that the population is perhaps more fragile than we think?

Phil: You can certainly make that argument. There was a number of new developments in cougar management this past spring certainly. In issuing them, Game and Fish Department has stuck to its guns in claiming that what we consider drastic change in cougar management, are necessary because, in their quote, “There are too many mountain lions.” Whether that’s the truth, I don’t think has ever really been adequately proven by them or anyone else.

Julie: And studies show that high hunting pressures actually can destabilize a cougar population and contribute to more incidents and issues. Gary Kohler is a wildlife biologist living in Washington, who I interviewed previously with The Mountain Lion Foundation, who speaks about when you remove the elders from the population, you essentially have these young and really juveniles on your hands, who are really trying to disperse and to take over new territory. By coming in and over hunting, you are upsetting a balance that the animals themselves have helped to create.

Phil: Yes. In the 2012 recommendations by Game and Fish Departments, there was a section that we found particularly egregious that essentially the agency said that it relied on Drs. Logan and Sweanor’s research to conclude that exploitation of a cougar population would increase public safety, and that is just not supported in the scientific literature, whatsoever.

Julie: So you referenced the 2010 modifications that the Mexico Department of Game and Fish proposed. Where are we now in 2012? What’s happened?

Phil: This past spring, the Game and Fish Department issued some new amendments to the bear and cougar rule, that were kind of slipped in under the radar that we definitely felt like there were some really drastic changes to cougar management contained in these amendments.

The biggest one is, like I mentioned earlier in the podcast, we helped Game and Fish Department institute a new management paradigm called the Total Sustainable Mortality, which accounts of all cougar deaths within a game management unit, not just hunting.

Well, that was pretty much thrown aside during the 2012 amendments and now cougar harvest which is total cougars killed through hunting is the only thing that’s going to determine game management zone closures from now on.

Julie: So that means if a cougar gets hit on the highway or succumbs to natural death, all of those kind of deaths are not counted?

Phil: That’s correct. They’re no longer counted. They’re counted, but they do not effect any sort of management changes, only hunting is going to determine what game and management zones are closed. It’s essentially working at a deficit of cougars due in the fact that you’re not responding to other forms of mortality to these cougars.

Julie: Development and road death, I would think, would account for a high percentage of cougar deaths.

Phil: Yes. It’s probably around 80 to 90 percent, I believe is what the department has claimed is the cause of mortality is hunting, so that hunting accounts for about 80 to 90 percent of mortalities is what the department claims. I’m not sure about that, but it really defies any sort of precautionary principle as far as managing a pretty rare species to not include these other forms of mortality like road kill or natural depredation.

Another really big change that occurred this past spring was, where the cougar hunting season was limited from October to March, it is now a year-round enterprise. You can go out and hunt cougars at anytime during the year. Also the bag limits for these hunters has doubled. Where you could only take one cougar per hunting per trip, now you can take two.

Julie: So what about mating season and when mothers have their children? That there’s just disregard for those seasonal changes?

Phil: That’s what it appears like, that the Game and Fish Department is now completely disregarding cougar biology and mating, as far as its overall scientific management of the species goes.

Julie: Who’s tracking those changes, just to see what kind of difference this is already making on habitat?

Phil:These new amendments haven’t been in place very long. They were voted in unanimously by the State Game Commission in June at their meeting. It remains to be seen what the effects on these populations is going to be. The wildlife biologists employed by the State are responsible for maintaining these studies of how it’s effecting cougar populations.

Julie: When the department makes it known that they are going to be considering modification of policy, do you see all kinds of interest groups, I would imagine, lobbying to be heard from biologist themselves to hunters to individuals such as yourself and the public, there are opportunities to come present your information for consideration, at some point. How good are they at making those opportunities available and known?

Phil: The amendments are published on the Game and Fish Department’s website and are open to a public comment period, so the State Game Commission holds one public comment period at some location within the state, at one meeting and then at the next meeting they vote yea or nay on changes in management on this. Both the environmental groups, as well as other groups like the hunting interest groups, are out there, generally at odds, although not always. It’s always an issue as far as who’s going to be heard, who’s gets their membership out better.

I would say that I think we have a game commission that’s much more stacked to the agricultural interests and hunter interests, than we have had in years past. The State Game Commission is a body that’s appointed by the Governor’s office. It’s been traditional to have at least one commissioner from the environmental communities sitting on that, but we haven’t really had that at all since 2010, which is quite disappointing when you look at the over-all percentages of what people use their public lands here in New Mexico for. The people who get out for hiking and especially wildlife watching, which has it’s own designation, far, far outstrip by many orders of magnitude the people who are out for hunting or angling or trapping. If this game commission was truly representative of what the public is using it’s public lands for, and public’s wildlife for, they should have a mostly environmentalist panel makeup, but they very much do not.

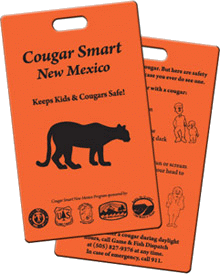

Julie: Let’s back up a minute because you were talking about the public outcry, and I know that one component of what Animal Protection of New Mexico does is something called “Cougar Smart New Mexico.” It’s an outreach program you’ve developed in collaboration with the Santa Fe County Open Space and Trails, but also some of the entities mentioned in our introduction, the New Mexico State Parks, and so on. Tell me about this outreach program and what are some of the kind of things it undertakes?

Phil: Because public safety is often used as a rational for managing or even over-managing of cougars to the point of expiration, we developed this program called “Cougar Smart” which has a number of materials which is distributed for free. We also give outreach talks, especially to families and children all over the state.

What it is, is basically information on safe and responsible conduct within cougar country. Just really tidbits about if you see a cougar, what’s the safe course of action: don’t run, look big, certainly don’t play dead, make a lot of noise. And also other really helpful tips like: always keep your dog leashed when out in cougar country, including national forest lands, walk in groups, make sure children stay near adults, things like that just to make sure that people stay safe and we don’t have – while attacks are extremely rare, they do happen. We had 2 fairly high-profile cougar attacks back in 2008. So just to be proactive in making sure people stay safe so these animals aren’t persecuted on behalf of a misguided approach toward public safety.

Julie: Are there any guidelines available for ranchers or those with livestock?

Phil: We don’t publish those. A number of other group do, including I believe Defenders of Wildlife does. I want to say The Mountain Lion Foundation has also produced materials on that, though, I could be wrong.

The total number of livestock loss from native carnivores, including mountain lions, but also wolves and coyotes, is extremely small. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s own figures show that. So we’re always trying to downplay the actual danger to both humans and livestock from these animals when far more head of livestock are lost to exposure, dehydration, even lightning strikes per year.

Julie: And cougars and other large predators can actually benefit prey populations, can’t they?

Phil: Absolutely. Definitely keeping deer and elk, and other ungulate populations in check, culling of the weak and through the trophic systems of biology, keeping deer and other populations in check benefits other animals including beaver, foxes, rodents, all sorts of creatures. Mountain lions really do have a very vital place within the ecosystem. So it’s disappointing to see when wildlife management seems to think they are an inexhaustible resource.

Julie: What’s the state of cougar research like today? Is there a healthy number of potential next generation of cougar biologists who are interested in working with your organization, who are helping to keep the figures current, the data current?

Phil: Right. We are always looking to collaborate with people who are really interested in working on cougar biology and all that. I don’t foresee it, as we’re kind of in a different political climate than we were back in the mid to late 90s when this Hornocker study was done with taxpayer money. I don’t see something like that happening again, but we’ll definitely coordinate with a number of biologists, and always welcome really good hard data on just what the mountain lion populations is and what the state of their wellbeing is.

Julie: And what do the habitat maps reveal now? Where are the healthy populations located in the state?

Julie: And what do the habitat maps reveal now? Where are the healthy populations located in the state?Phil: They’re all over. New Mexico has kind of a band of the Rocky Mountains going down through the central part of it, and so that’s where we’re seeing a lot of the populations, although there are more isolated clusters as well in the southeast and northwest sections of the state as well.

Julie: Tell me what some of the current projects are on the table for you and your peers.

Phil: We’re continuing to get the word out about the “Cougar Smart” program to school groups. I’ve had a lot of interaction over the past year with groups like the Valles Caldera National Preserve. They had their annual marathon back in June. Every year they have an animal theme for it, and this year it was year of the cougar. It was really fun to coordinate with the Valles Caldera National Preserve on getting information out, as well as distributing the “Cougar Smart” materials

We also had a lot of good interaction with the State Girl Scout Association here. It’s been great working with them. They have a number of really interesting badges, projects that their scouts do related to wildlife management. So, it’s been really fun working with some of the young, what I would consider potential activists, certainly. Young kids really looking to learn more about the issue.

Julie: Absolutely.

Phil: We’ve recently manufactured some metal versions of our “Cougar Smart” informational signs for the state park system, getting that out to a number of locations around the state, which has been a great development, too. And, we’ve been talking with the Forest Service for a couple of years now about possibly adapting this “Cougar Smart” program to the national campaign, similar to their “Be Bear Aware” program.

Julie: Nice. Are there other advocacy groups in other states that your group partners with or looks to as a role model, for example, on how to implement new strategies?

Phil: Oh yeah, certainly. Mountain Lion Foundation has always been quite supportive as have the Cougar Fund. We continue to work with the Hornocker Institute, as well as the biologist, Sharon Negri, on just about getting responsible management to cougars, not just in New Mexico, but across the west.

Julie: Can you conclude with a cougar story of your own? Have you ever seen a cougar in the wild?

Phil: No. I never have, personally. It’s kind of an ongoing dream. My parents live up in southern Colorado, in the San Luis Valley, and they saw a mountain lion probably about 500 yards from their house recently, so I was really jealous for that. I’ve definitely heard them when I’ve been out camping, but as of yet, I’ve not seen them. It’s kind of an on going hope that I will someday.

Julie: They’re elusive creatures, aren’t they?

Phil: Very.

Julie: Well, Phil Carter, a pleasure to speak with you. Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us today.

Phil: Great. I really appreciate it. Thanks very much.

Julie: And good luck with your next wave of projects.

You’ve been listening to Phil Carter, wildlife campaign manager with Animal Protection of New Mexico. I’m Julie West with the Mountain Lion Foundation. Thank you.

Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for noncommercial use. For more information visit mountainlion.org.

Listen Now!

Listen Now!Listen to the interview from MLF’s ON AIR program, podcasting research and policy discussions about the issues that face the American lion.

Julie: Hello. I’m Julie West, your host. Thank you for listening to On Air with the Mountain Lion Foundation. My guest today is Gary Koehler, wildlife research scientist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife from 1994 to June 2011.

Gary’s expertise includes thirty years of research on a variety of carnivores including the cougar, black bear, Canada lynx and snowshoe hare. He continues to participate in cougar and lynx research in Washington and advise projects concerning tigers in China and snow leopards in Mongolia.

For the past eight years, Gary’s been involved in Project Cat, a community outreach program that engages public school children, teachers, and the community with hands-on environmental educational opportunities in science fieldwork. Prior to his affiliation with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Gary served as former research associate with the Hornocker Wildlife Institute and senior lecturer at Moi University in Kenya. Additional biographical information for Gary is available on the Mountain Lion Foundation web site. Hello, Gary.

Gary: Hi Julie. Good to speak to you.

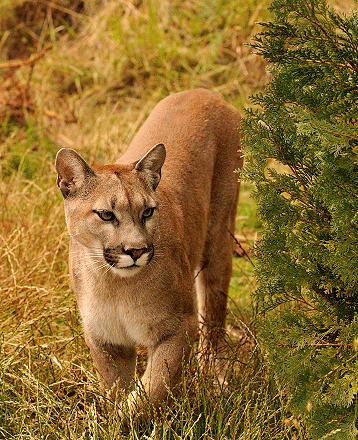

Julie: Thank you so much for being with us today. I want to start by observing when there are increased news reports of cougar conflicts with humans or cougar livestock and pet encounters, it seems the common assumption is that, “Oh, cougar populations must be growing,” and people can really panic about this. You know, “Get your guns out, aaahhh!”

But your research suggests that there’s more to the story than meets the eye and that this is actually maybe a misnomer, that poorly designed hunting policies might be triggering this increase. What are you finding, and how can you address this public perception?

Gary: Julie, in Washington State we’ve studied cougars here over a decade, and we’ve looked at cougar populations in five different areas; very distinct ecotypes in the state. What we’ve done in this long term research was really unique and instrumental in unraveling some of the mysteries about their populations and how they respond to hunting.

What we found in one area where we had studied cougars and where the community participated in this process called Project Cat, Cougars and Teaching, the area received a relatively low harvest rate of about 10 percent per year.

The cougars, like elsewhere in the west, can live in close proximity to people; particularly in developed areas. In fact, that’s what they did there, and there were very few people complaining about cougars.

That low harvest rate resulted in an older-age population, and the animals there were able to go about their lives, regulate their own numbers the way they evolved with the territoriality and dispersal of young male cougars that were born in the area.

Then we looked at cougar populations in the northeast part of the state where the harvest rate was more than double that. It averaged about 20-23 percent per year. As a result of that, this resulted in a quick turn over of the population. The average age of the cats there were about half that of the other areas with low harvest, the Project Cat study area.

The average age was about three years old where the cougars were harvested intensively, in contrast to six to seven years old where there was that lower harvest rate.

As a result of that, when you continue high pressure like that, you’re creating these territorial vacancies. You’re creating an opportunity or a vacancy where young dispersal-age cats, inexperienced cats, are going to have an opportunity to find a vacancy and set up their own territory.

Also what happened there, the high harvest really disrupted the social organization, particularly for the males. Rather than being exclusively territorial and having exclusive areas and parsing out the landscape, these young-age cougars, their home range areas were much larger than in the control where the harvest rate was low and like two to three times as large.

The males were basically stacked upon each other. So there’s increased opportunity for — if you live on a site in the northeast part of the state — you could be visited by three different resident or establishing cougars, male cougars. (Where if you have an area where the harvest rate is low, that would be the domain, and your area might be the domain of one male cougar.) So the probability of encounters basically goes up.

Also the cats are inexperienced hunters. They haven’t had the experience of living around people. They’re kind of like juvenile, inexperienced people or a variety of other mammals including ourselves.

Julie: Teenagers, my teenagers (laugh.)

Gary: True. The inexperience, plus higher probabilities of encounters with people, leads to a potential for increased conflict and increased complaints.

Julie: So the key really does hinge then on, it seems like, if I am understanding you correctly, the heavy hunting is taking out the older males and the population structure is shifting. You have these younger juvenile cats who need to establish their own territory, so they’re more likely to come onto conflict without the dominant male cat kind of keeping that social order intact.

Gary: That’s correct. That’s exactly what we found. This was a unique study, and we were able to compare two different study areas with basically two different harvest intensities, and that’s exactly what we discovered.

Julie: When your data is this compelling, and that’s not to imply it’s not without controversy because I’m sure it is and that people are interpreting this in a number of ways. Maybe you could address that in a minute. But how can you, then, affect policy or what’s the next tier? Where do you take this data? Where does it go from there?

the high harvest really disrupted the social organization, particularly for the males

Gary: Here in Washington State we are attempting to affect policy. We’re trying to take this science and this understanding that we’ve found and to attempt to minimize or lower the harvest in any one particular area.

What you create is an unregulated harvest structure or an area where access is easy in the winter time. Hunters can get in where there’s lots of roads, and if you have snow, cougars are particularly vulnerable. In these areas you can create conditions for a high harvest rate or a high hunting mortality, in an area with high roads and good snow conditions.

You can create a situation just like what we explained and that population is going to be dominated by these young inexperienced cats coming in and taking over vacant areas that were once occupied by older-age resident male cougars. What we’re trying to do is distribute the harvest or distribute the hunt effort on the landscape where hunters don’t necessarily go, where the picking’s easiest, where the road density is high and where you’ve got good snow conditions because cougars can be quite vulnerable under those conditions.

Julie: So you’re saying that maybe state agencies like the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife can dictate those parameters, can have a say in where those locations should be, and offer the cats to the hunters, but maybe not make them such easy targets.

Gary: That’s correct. Basically distribute the hunter harvest over a wide area so the hunters are not necessarily attracted to the areas where it’s easiest to get a cat. I know everybody wants to be successful, but if you’ve got areas with high road density and good snow conditions, you can seriously impact a cat and cougar population with the result of a whole change in the population structure and potential complaints going up.

Julie: Does that necessarily assuage fear? You still have public perception to deal with. How is that piece of it addressed?

Gary: Well, what we’re trying to do, and this is true with a lot of agencies in the west, as well as private entities like The Cougar Fund and The Mountain Lion Foundation, is educating the public, and that’s a very important part of all of this. Agencies are trying to step up and play that role as well. It would appear, at first hand, if there’s more cougars being seen, that one would think, “Oh, there’s got to be more cougars out there,” but it may not necessarily indicate that.

I saw a cougar just the other day on a hike here in the snow. Obviously it was a young cat, and cats are curious. And the old adage, “curiosity killed the cat,” you know young cats are vulnerable &mdash young cats are curious &mdash and very often that’s what you see is younger-aged animals. It’s not necessarily an increase in populations.

In fact, cougars are very good with their territorial makeup of their population, spacing themselves out on the landscape so that they don’t overwhelm the prey population. There’s a limit to the number of cougars that you can have on the landscape.

Julie: Is it possible for the cougars, if you were to greatly back off on the hunting or greatly change the hunting regulation to give them a break, is it possible it could go the other way?

Gary: No, I don’t think that there’s a danger of cougars getting out of control. I think there’s a good example of that in California where there hasn’t been any harvest, or public harvest of cougars. You don’t get reports of cougars overwhelming the landscapes in California.

Julie: It does seem like so many things are stacked against them, with highways and development and loss of habitat, that those would be built-in ways of limiting their numbers already.

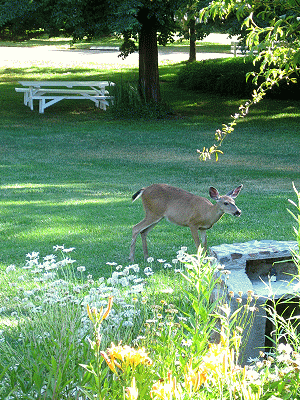

Gary: Basically what dictates cougar numbers is habitat, and definitely is prey numbers. So if you’re going to lose habitat, you’re going to lose prey: elk and deer, and that’s going to impact cougar populations.

The downside of development, particularly in cougar habitat or deer habitat, is often as residents we like to see deer, so we attract them into residential areas by things that we plant. We even provide food for them. We feel sorry for them in the winter, and that too leads to serious problems because once you start attracting a major prey species like that, there’s a potential for attracting a predator and that predator in the deer range is a cougar.

The downside of development, particularly in cougar habitat or deer habitat, is often as residents we like to see deer, so we attract them into residential areas by things that we plant. We even provide food for them. We feel sorry for them in the winter, and that too leads to serious problems because once you start attracting a major prey species like that, there’s a potential for attracting a predator and that predator in the deer range is a cougar.So that is an area that it is not only loss of habitat through development, but that impact can be magnified by enticing deer into residential areas and have an impact on the cougar population by attracting the cougars into these residential areas.

Julie: And where does trophy hunting figure into this? For me, I think of trophy hunting as being in a unique category outside of hunting. But maybe it all stems from the same desire to — not always — but to sort of conquer and literally take the trophy from nature. That’s a major contributor of decline in cougar populations, isn’t it?

Gary: Well, it can be in some areas. I mean cougars are a highly prized game species. There’s few people that kill them for food, but they like to have them as a trophy animal. I think there is a certain amount of off-take, if you want to put it that way, or hunting that you can permit in an area. But the older toms, they’re larger and they’re bulkier. They’re much more valued trophies than a young-age cat or a female. They’re just bigger, maybe twice the size of a female in weight, so they’re the valued trophy.

But the thing of it is, when you’re taking those trophy-aged animals, those older males, you have the potential to create a population sink if you kill a lot of these large older males in an area. You’re killing off the older resident toms that have well established territories, and kind of dictating the demographics in the culture and the policy of cougar behavior. Those older-age animals, those trophy-age animals are a very important part of the population. They help regulate the numbers. They help force young-age animals to disperse, and they basically regulate the numbers of cougars on the landscape through territoriality. So they have a very important role in the natural scheme of things.

Julie: It should make sense. Elders in our own human societies have played such a critical role in maintaining order and stability and passing on the traditional wisdom and knowledge. Why wouldn’t it be so for the animal world as well?

Gary: It’s definitely true. That has been documented very clearly in elephants, documented very clearly in a lot of our primary species in Africa and Asia, and a lot of our ungulate populations too. They’re matriarchal. The older cows pass on to the younger calves travel routes. There is culture in these animals, and these older animals do play a very important role in not only seeking out and showing the younger generations where to go, but in the case of cougars, regulating the numbers of cougars on the landscape in territoriality.

You’re killing off the older resident toms that have well established territories, and kind of dictating the demographics in the culture and the policy of cougar behavior.

Julie: So how can the Department of Fish and Wildlife communicate to hunters, or what is an ideal goal in communicating to the hunters? You suggested one strategy of not making it so terribly convenient to get to the cats, number one. But how can someone resist taking out a big cat if that’s their goal. If, as you say in trophy hunting, the bigger the cat the better, knowing that that bigger cat is likely going to be one of those older, mature elders who are needed, can you limit the number of older male cats you can take out?

Gary: I think that’s kind of the key is limiting the number of older cats that are harvested in the area. Basically putting a limit or a quota on the number of cats that are harvested on a particular drainage, particular game management unit, or population management unit, whatever the management designation for the area might be. Limit the number of animals harvested in a particular area.

I think a corollary to that is rather than create situations where cougars are very more vulnerable because of good road access, if you can distribute the hunt throughout the region, throughout the state, so you’re not taking out all of those older animals out of a particular watershed.

You might take one out of the watershed, then leave two others because that area that was occupied by the cat that is killed, it’s going to be occupied by a young-age tom. He’s going to come in and discover this vacancy and set up shop there, and it’s those other older, neighboring resident toms who are going to basically confine him and say, “Ok, this is your territory. You stay there.”

You might take one out of the watershed, then leave two others because that area that was occupied by the cat that is killed, it’s going to be occupied by a young-age tom. He’s going to come in and discover this vacancy and set up shop there, and it’s those other older, neighboring resident toms who are going to basically confine him and say, “Ok, this is your territory. You stay there.”But if you take out all the toms in this area, then what you’re going to do is basically create a social chaos in there and a potential for turmoil as we discovered in the northeastern part of the state where we studied cougars.

Julie: What you propose is so reasonable and logical in my way of thinking. What could the resistance to that possibly be?

Gary: I think some of the resistance is, with most state agencies, wildlife management agencies; we still have this idea ingrained in our psyche that cougars are indeed predators. They don’t require any special management needs or, “Let’s just harvest them but not worry about it. I mean they’re going to reproduce.”

I think what we’re trying to deal with here, and what we’ve got to convince our own agencies is that, “Hey, there’s a better way to manage these large predators,” particularly cougars and that the evolution of the cat is all a part of this. We need to be aware of that behavior in this territoriality of these cats is a unique thing about cougars — not necessarily unique about cougars, but it is certainly characteristic of all of the cats — and that we should be aware of this when we’re setting up a management strategy.

Julie: It seems to me that these agencies such as your own Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife that you were affiliated with for so many years, they are working with research scientists such as yourself. They do have the benefit of this incredible biological knowledge just by association of their partnership and their own team members, so it must have been very challenging, but also hopefully rewarding, for you to work within that system and to find that maybe their policies didn’t always agree with you, but also to find that maybe you could help effect change from within that system

Gary: Well, we are trying, and we’ve done that. We’ve put a lot of effort in it. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife did sponsor most all of this research, or helped sponsor most of the research that we’ve done in this state, as have the universities here: both WSU, Washington State University, and the University of Washington has been involved as well.

So they are receptive, but there’s still this notion in some management people and personal that predators are different. They’re just considered something different: vermin.

It’s a real challenge to try to change perceptions of carnivore — large carnivore — management. We so often considered them as predators, but we are making inroads. There are changes, but we also have to pass regulations and get the approval of wildlife commissions.

We have wildlife commissions here in this state and elsewhere. Other states have them too. That is where the hunting public has a voice, and they’re often reluctant to make some of these changes because they don’t want their opportunities compromised. We need to start applying the science of the ecology of these animals to our management.

Julie: Were you ever in a situation, at conferences maybe, where you could really get down into some serious debates with fellow game and fish colleagues?

Gary: Yeah, we did. Every three years, or something, agencies and non-governmental agencies have a program called The Mountain Lion Workshops. There all of the agencies, state agencies, convene, and you have great opportunities to talk about that.

We’ve in fact presented some of our ideas to the last Mountain Lion Workshop and that was this spring. They’re aware of what we’ve done. They’re aware of what can be done to better manage things. We do have dialogs with an exchange of ideas with other agencies, state agencies, and we have discussed this. There’s getting to be a greater receptivity to some of these ideas but it’s like any change, it takes a while. You just have to be persistent and really present a convincing argument.

Julie: The argument might not need to be so convincing for your fellow game and fish colleagues perhaps, but it seems that the greater challenge would be their community, their community of hunters.

Maybe this idea that academia, the scientific knowledge coming from the ivory tower of academia, doesn’t really relate to the average person who just wants to have his gun and have free reign and go wherever he wants to and, “Why should a scientist at a university coming up with data tell me what to do?” Do you think that those are just some real basic challenges?

Gary: There are those challenges, but we have those same challenges within our own department. Just as there are different philosophies within the hunting community, there are some hunters that are really receptive to these ideas we’re talking about.

Julie: That’s a good point. Thank you for mentioning that.

Gary: Within agencies there’s some of the kind of the “good old boy” attitudes too that are tough to change. But the thing of it is where we’re trying to get in this state and has been demonstrated elsewhere, particularly in California, is the role of science in unraveling some of the mysteries of this animal and trying to implement some of these findings in the management.

We’ve got our own people to convince. There’s a lot of positive movement. I think we’re all on the right track, and we’ve got the momentum. But it’s not smooth sailing, either with the management agencies or the hunting communities. But there are people that get the picture, and they understand the need to make some changes.

Julie: I was just reading a story in the news recently, I’m sure you know about it, of a hunter in Washington State who shot and killed a mother cougar and consequently orphaned her three kittens. The thing is the hunter said he knew it was illegal to shoot the mother. He was aware of her kittens, but he shot her anyway.

It just seems that despite reason and the best efforts of yourself and others who are working toward achieving this balanced human/wildlife dynamics, there will always be examples of this blatant disregard for the law and that you’re really up against some deeply rooted entitlements to take at any costs.

That’s frustrating, but I like looking to your work of Project Cat and young people as being the hope to the restorative justice side of that. Maybe you can tell us a little bit about how that’s going and how you’re empowering people with this knowledge.

Gary: I think Project Cat was an experiment, but I think a very successful project. What I’ve learned more than anything is, really, the way to change attitudes within the community is through the kids in the schools, where we had with Project Cat we involved, anybody from 8th graders and older. We took them out on these captures, and they followed us around the woods to capture animals. That knowledge that they gained and acquired from working with us…

Julie: Capturing them for the purpose of radio collaring them?

Gary: Radio collaring them, and studying them, and finding out what their relationship is on the landscape and how many animals, and what their predation ecology was, and relationships with their use of space with where people live.

These kids have a first hand view and a first hand understanding of all of that because they got to work there. They took that understanding home. They talked about it with their extended family at thanksgiving dinners. In fact, it was a lot of these kids that made the greatest impact into that community, telling their grandparents not to feed the deer because it’s going to attract predators.

It was the kids that were the champions. They were the ambassadors in the community and had the most affect on changing attitudes about cougar ecology. I think when we left there, that community was certainly supportive of Project Cat. Everybody in the community was deeply involved in it and really understood much better the role of the cougar in their neighborhood and as part of their neighborhood. So it was the kids and education through the schools and getting the kids involved that made a difference in that community.

Julie: Seems like we need a network of Project Cat programs across not only Washington but the northwest and the southwest too.

Gary: Yes, on a variety of topics. Cougars are one of them and cougars are very important because they hold such … they’re such a beautiful animal but we still fear them. Just unlocking that mystery about the lives of cougars in that community and having the kids take that home really did make a big change in that community

Julie: Very important work. Well, we’re running out of time, but I do want to ask how your knowledge of big cats in wildlife management here in America is informing your research in countries such as Africa and China. Are there relations in your findings?

Gary: Actually there’s the old adage “a cat’s a cat,” and pretty much they are the most amazing and most sophisticated of the predators on our planet, most highly evolved.

Pretty much they just come in different disguises whether it’s a tiger or a mountain lion or a lynx or a bobcat. They have a lot of those same patterns. Those understandings of how snow leopards might relate to the villagers and depredation on villagers livestock is not a lot different than dealing with depredation issues here in the U.S. when it comes to cougars depredating on domestic goats or sheep or for that matter, wolves.

And I think that there’s a lot we can take home and apply elsewhere about the dynamics of predator communities and how we as humans live in these communities. So we pretty much take all of that information and transplant it elsewhere.

Julie: Maybe we could end with you sharing a story, if you’d like to, of one of your own encounters with a mountain lion.

Gary: It was just the other day my wife and I — this Saturday in fact — we decided we just had some fresh snow and we went for a hike up to these little lakes above Wenatchee and… sorry, the dog is barking. Here, I’m going to step outside.

Julie: You don’t have cats? (laugh)

Gary: No. I’ve got neighbor cats that seem to enjoy me, so we don’t need a cat here because we have cats all around us that come by.

But what is amazing to me is these cats, these cougars; they’re so secretive, they’re so stealthy. They can be close by you, and you would never see them there. You might see their tracks.

But like I said, Saturday on our hike out from these little lakes there was a movement off the side of the road as we were driving out, and my wife says, “I think that was a cougar.” So we stopped, and I got out. I looked over there, and sure enough, this young cougar stepped out. It was a young animal, just by its features, but it was not spotted so it was maybe a year and a half, two years of age.

That animal just stood there and watched us from not more than about thirty or forty yards away, and it was so awesome. I’ve spent 15 years of my professional career working with these things, and I never get tired of looking at them. They’re such an amazing and such a beautiful animal, and to be able to catch a glimpse, not to mention looking at one looking at us. It was truly amazing.

Julie: Yes. Well, thank you so much, Gary, for speaking with us today.

Gary: Well, it was my pleasure. Thank you very much for giving me the opportunity. These are fascinating animals, and I appreciate you letting the public know about the role of these amazing animals.

Julie: Well, thank you so much Gary. It’s been a great conversation.

Gary: Hey, thanks. Take care.

Julie: All right.

Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for noncommercial use.

Mountain Lion Foundation created an interactive overview on what happens when mountain lions prey on pets or livestock in California. It’s always sad when this happens, devastating for the owner, often lethal for the lion, and is usually an avoidable situation. See the story map here

Historically, the word “depredation” has been used in the context of a military raid or pillaging a village. In the dictionary, it is defined as:

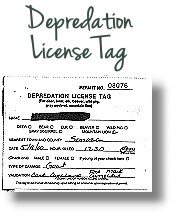

Wildlife management agencies primarily use the word depredation for instances where a wild predator attacks or preys upon a domestic animal, such as a family pet or livestock. In places where it is legal to retaliate for this “damage or loss” by having the nuisance wild animal killed, a Depredation Permit is issued to the pet/livestock owner.

Coincidentally, the word is the combination of the prefix “de” meaning removal or reversal, and the root “predation,” for a wild animal hunting prey. Because of this, the term “de-predation” is also sometimes used to describe the depredation permit in terms of it being the removal of a predator.

So, the initial predatory attack and the resulting permit for killing the lion both use the word depredation, even though a slightly different definition may be implied. Either way, if a mountain lion damages a person’s property in California, a permit must be issued to have the lion killed if one is requested (see California Fish and Game Code Section 4803).

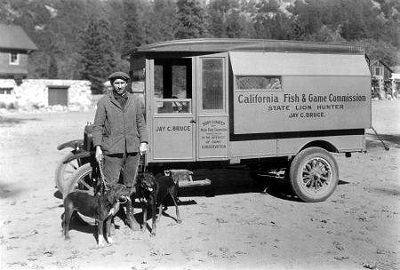

Ranching began in North America during the 16th century when early explorers and settlers first brought over livestock from Europe. Over four-hundred years later, the ranching industry has become a cornerstone of American culture. During WWI, increasing cattle production to support the troops was seen as a patriotic duty. Wild animals were either viewed as competition (deer, elk, bison, etc.) for grazing resources, or as a liability (wolves, cougars, prairie dogs, beavers, etc.) because of predation or causing damage to ranching land. Thus, wildlife was a problem and viewed as something that needed to be controlled and eliminated.

Though we now know better, many of the beliefs from a century ago still exist today:

Mountain lions are territorial and when one is killed, multiple younger lions may move in to fill the space. Younger cats are more likely to be tempted by domestic animals and may continue the cycle of livestock losses and having lions killed. Shooting a lion does not undo the death of a domestic animal, does not prevent future livestock losses, and costs tax payer money.

Florida is the only state that will not issue depredation permits for lions (referred to locally as panthers) that threaten or have killed domestic animals. Residents are allowed to scare a panther away if it is on their property or stalking a pet, but they may not injure or kill it. This policy is due to panthers being federally listed as a critically endangered species with less than two-hundred left in the wild. Every single panther is essential for the recovery of the species.

Because they do not have the luxury of a depredation permit, Florida residents are aware they must take preventative measures. No other state values their lions enough to enact similar policies and require its citizens to be proactive.

Because they do not have the luxury of a depredation permit, Florida residents are aware they must take preventative measures. No other state values their lions enough to enact similar policies and require its citizens to be proactive.

In most situations, there is no limit to the number of depredation permits a person may be issued, nor are there prerequisites for animal husbandry (such as not tying a goat to a fencepost over night), and no required education or assistance after the incident to help the owner prevent future losses.

In California there are two notable exceptions, the Santa Ana Mountains and the Santa Monica Mountains. In each of these areas, CDFW recognizes that the mountain lion population has become too imperiled, and individuals too important, to manage depredations without restrictions. In these areas, landowners who lose animals to mountain lions are given additional help to prevent future losses rather than lethal removal permits at the onset.

While killing a lion for depredation is historically common and culturally acceptable, it is not a productive solution and is an unnecessary loss of life. MLF has created a variety of information and tips for keeping domestic animals safe and coexisting with wildlife. These resources for non-lethal animal husbandry techniques are available and explained more thoroughly in the Protecting People, Pets and Livestock section of this website.

Click on any of the bullet points for more information.

If a mountain lion is seen on one’s property, or evidence of a lion is found such as scat, tracks, or a deer kill, a phone call to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife may result in an officer coming out to investigate, or they may simply record your sighting over the phone. Because there has been no damage or immediate danger, a depredation permit is not issued. Seeing a lion is not legal cause to kill it. If the lion has not threatened any people, pets, or livestock, usually it is left alone to move on naturally.

However, if an officer (CDFW or local law enforcement) responds and the lion is present, the situation may be classified as a Potential Human Conflict: A mountain lion that is found in an unusual location and/or is demonstrating unusual behavior that could reasonably be perceived as having potential to cause severe injury or death to humans (a possible situation that may exist before a lion becomes an actual public safety threat).

However, if an officer (CDFW or local law enforcement) responds and the lion is present, the situation may be classified as a Potential Human Conflict: A mountain lion that is found in an unusual location and/or is demonstrating unusual behavior that could reasonably be perceived as having potential to cause severe injury or death to humans (a possible situation that may exist before a lion becomes an actual public safety threat).

Under a n ew law (§4801.5) that went into effect January 1, 2014 only a mountain lion posing an imminent threat to human life may be killed for public safety. This is defined by the lion exhibiting one or more aggressive behaviors directed toward a person that is not reasonably believed to be due to the presence of responders. All situations that do not meet this threshold must be resolved with non-lethal force (hazing, tranquilizing, capturing, relocating, monitoring, etc.).

ew law (§4801.5) that went into effect January 1, 2014 only a mountain lion posing an imminent threat to human life may be killed for public safety. This is defined by the lion exhibiting one or more aggressive behaviors directed toward a person that is not reasonably believed to be due to the presence of responders. All situations that do not meet this threshold must be resolved with non-lethal force (hazing, tranquilizing, capturing, relocating, monitoring, etc.).

If a mountain lion is found in the act of attacking a domestic animal or is seen as an immediate threat to human life, it may be killed by a resident, without repercussion, as long as the California Department of Fish and Wildlife is immediately notified after the incident. CDFW will confirm it was the only option to prevent loss of life to people or property (pets or livestock being the property). A verbal depredation permit can be issued over the phone and followed up later with the necessary documentation.

It is highly recommended to contact CDFW first, before any action is taken against the lion. If the Department finds there was no immediate danger, a shooter can be prosecuted for poaching since mountain lions are a specially protected mammal in California. The local police department and/or county sheriffs office can also respond to mountain lion-public safety calls to a 911 operator.

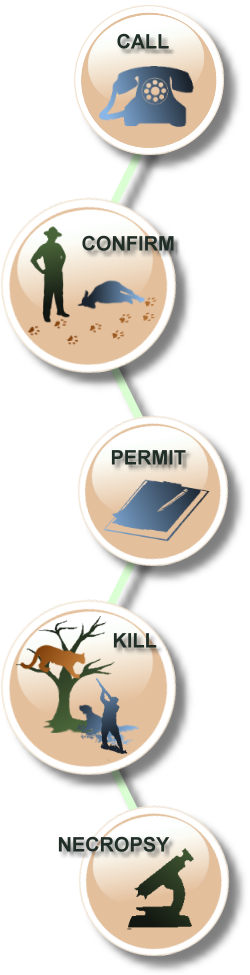

If a domestic animal (pet/livestock) is injured or killed by a mountain lion, the owner has the legal right in California to have the mountain lion killed. The following steps give an overview of the process.

Depredation Permits expire after ten days because lions roam such large territories. A lion seen in the area after that time may not be the same one that caused the damage. Many biologists believe younger, dispersing lions are more likely to cause depredation, and these cats will often travel hundreds of miles to find a home range. A juvenile dispersing lion may only stay in one area for a few days. Adult resident lions will usually keep the younger ones out. Killing a non-depredating adult lion is not a good idea, as this opens his territory for several younger lions to move in and may ultimately increase conflicts.

Mountain lions have been a specially protected mammal in California since the passage of Proposition 117 in 1990. Under the law (California Fish and Game Code, Section 4800), even deceased lions or any part of a mountain lion may not be possessed (unless the owner can demonstrate that the mountain lion, or part or product thereof, has been in the person’s possession since June 6, 1990). All mountain lions killed for depredation must be turned over to CDFW. By law (§4807(b)), the Department is required to conduct a complete necropsy on each carcass. The findings from these examinations are made public through an annual report submitted by the California Fish and Game Commission to the Legislature.

In 2011, the Mountain Lion Foundation worked with Senator Fuller and Assembly Member Huffman to pass legislation (Senate Bill 769) to allow educational facilities to obtain permits to acquire and display deceased mountain lions. Though no longer able to fulfill their important role on the landscape, dead lions can help us to better understand and protect the species. To learn more about obtaining a lion carcass, visit Mountain Lion Educational Displays in California.

On December 15, 2017, California Department of Fish and Wildlife issued an amendment to the Mountain Lion Depredation, Public Safety, and Animal Welfare Policy that now allows CDFW to tailor their response to the specific circumstances of a depredation incident, providing a wider variety of management tools and greater protection for livestock, people and mountain lions.

As a result of these efforts the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s has amended their Policy to provide additional protection to endangered mountain lion populations in the Santa Ana and Santa Monica mountains.

A three-tier stepwise process in these areas has been adopted:

First Depredation Event

Second Depredation Event

Third Depredation Event

Almost all state game agencies keep track of the number of mountain lions killed annually for depredation. Some states even go as far as recording the breed of domestic animal lost and if preventative measures were implemented. The Mountain Lion Foundation requests copies of these reports and keeps track of mountain lions killed in each state.

Residents who do not wish to have an offending lion killed do not have to report pet/livestock depredation losses to their state game agency. In addition to the number of lions killed under depredation permits in each county, California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife also keeps track of the number of depredation permits it issues.

In California, the Department of Fish and Wildlife is the agency responsible for issuing depredation permits, keeping track of the number of lions killed, and conducting a necropsy on each carcass. However, because the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s Wildlife Services branch is the agency that hires the county trappers who actually hunt and kill depredating mountain lions, they also document incident reports and lions killed.

The USDA’s parent agency, APHIS, maintains detailed records of all wildlife damage reports and the inventory of kills. On their website, APHIS lists reports from 1996 through 2014 according to fiscal year.

| Year | Depredation Permits Issued |

Lions Killed (CDFW Records) |

Lions Killed (WS Records) |

Necropsies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 208 | 105 | 110 | N/A |

| 2004 | 256 | 120 | 133 | N/A |

| 2005 | 209 | 116 | 120 | 14 |

| 2006 | 169 | 87 | 115 | 28 |

| 2007 | 238 | 150 | 137 | 42 |

| 2008 | 144 | 60 | 123 | 16 |

| 2009 | 135 | 70 | 103 | 9 |

| 2010 | 132 | 59 | 108 | 13 |

| 2011 | 137 | 76 | 104 | 15 |

| 2012 | 137 | 62 | 77 | 7 |

| 2013 | 148 | 62 | 28 | 59 |

| 2014 | 216 | 89 | 78 | 51 |

| 2015 | 256 | 107 | N/A | 83 |

| TOTAL | 2,385 | 1,163 | 1,236 | 337 |

The provision to conduct a necropsy on every mountain lion carcass turned in is intended to provide CDFW and the legislature with critical information needed to properly ascertain the health and sustainability of California’s mountain lion population, and to determine whether or not the depredation permit system is being abused.

Based on a 2013 report by CDFW, only 25 percent of the mountain lions examined from 2006 to 2012 contained the remains of pets or livestock in their stomachs. If this percentage is extrapolated, then hundreds of lions have died needlessly. We must ensure that proper measures are in place to definitively identify offending mountain lions.

The Mountain Lion Foundation is looking into reforming the depredation process both in California and other states where lions are needlessly being killed. To stay up to date on our projects and to join us in this fight, please become a member today!

Listen Now!

Listen Now!Listen to the interview from MLF’s guest appearance on Slice of Nevada as we discuss current issues facing the American lion, including hunting, trapping, ecosystem impacts, and population data.

A very special thank you to America Media Matters and Slice of Nevada for allowing us to repost this audio segment.

San Benito County is a place like no other, and yet could be mistaken for many other small towns within California. October is a dry month for most of the state, the rolling hills to the east and the farmlands that dominate the landscape were awash in hues of brown and yellow. Gorgeous Pinnacles National Park is a short drive south from any of its small towns and communities. Hollister is the seat of the county and holds a majority of the human population; unbeknownst to many residents this is also an important area for Central Coast mountain lions.

This was our home for the week of October 14th as fellow wildlife biologist Shadee Kohan and I assisted with gathering signatures for a citizen’s referendum petition to halt action taken by the Board of Supervisors and put the matter of growth and development in the area on the ballot so that local people that will contend with the consequences can weigh in on the issue at the polls.

The fear that beautiful San Benito County will soon become an extension of the Silicon Valley was palpable; a life-long resident who grew up on a cattle ranch purchased by her grandfather was brought to tears by this prospect. As is often the case, what is beneficial to wildlife is also beneficial to the people that share the land.

Through our time there, along with the efforts of volunteers before and after us, PORC was able to gather twice the number of signatures needed to qualify for the ballot.

However, the battle is not over yet as PORC members will continue garnering support for their cause, helping residents to understand these issues and the far reaching impacts.

Getting people out to vote in the March 3rd election will be the next steps in an ongoing mission to Preserve San Benito County’s Rural Communities.

For future updates visit preserveourruralcommunities.org.

It rained on the Preserve earlier this week! Just a light rain in the early morning, not lasting long but it may have been long enough to trigger a territorial behavior in mountain lions called scent-marking. Mountain lions mark their territory in a few different ways, including marking a pile of dirt with feces or urine, known as a scratch pile, as well as scratch marking on trees, known as claw raking.

If our Preserve lion is a male considering claiming some territory here, it may be that he was out doing some marking just after that rain. While lions constantly patrol and mark their territory to send a clear signal that the area is occupied, a perfectly sensible time to go out and ‘re-apply’ would be just after a rainfall, when scents would be diluted and washed away.

If our Preserve lion is a male considering claiming some territory here, it may be that he was out doing some marking just after that rain. While lions constantly patrol and mark their territory to send a clear signal that the area is occupied, a perfectly sensible time to go out and ‘re-apply’ would be just after a rainfall, when scents would be diluted and washed away.

Male mountain lions can leave scat in the middle of a road or pathway or if they’re actively scent-marking, they’ll use their back legs to kick together some dirt, twigs and leaves into a scratch pile and then either defecate or urinate on the pile, leaving these calling cards along the borders of their territory. Scent marking becomes particularly important when a male lion’s range overlaps with another male lion’s area or when a female lion in heat is nearby. Will this lion be so motivated to scent-mark if he doesn’t feel a threat from neighboring lions or smell a willing female? We can’t say. It depends on what this lion thinks about the habitat he’s navigated to on the Preserve.

Regardless, this could be good news for our camera team and we’ll find out at our next camera check whether this lion was busy walking perimeter areas, and perhaps padding by our camera locations on his scent-marking mission!

—

The Bureau of Land Management initiated a mountain lion study on the Cosumnes River Preserve in collaboration with the California Department Fish and Wildlife in 2014. Currently, the study is being carried out by an all-volunteer crew of dedicated individuals who receive support and oversight from the Bureau of Land Management. The Sacramento Zoo has awarded a grant to the Mountain Lion Foundation which has allowed the Foundation to purchase and loan ten trail cameras to the Preserve to help carry out this study. The goal is to find and document a mountain lion on the Cosumnes River Preserve.

Be advised: This article contains graphic images of animal remains.

Whether you are a wildlife biologist, cattle rancher, small organic farmer, or just an outdoor enthusiast, learning to accurately interpret the feeding signs of carnivores can enrich your natural experience, protect your livelihood, and ensure accuracy in data collection for wildlife research and management. Centuries of folklore and decades of Hollywood films have portrayed carnivores as blood-thirsty killing machines, slaughtering livestock and humans for sport, and the average person in the 21st century gravitates towards the most dramatic and fearful explanations when encountering a carcass in the woods. I have seen people swear that a deer they found had been killed by a mountain lion despite the complete lack of feeding sign on the carcass and the presence of a highway just yards away. Interpreting the feeding signs of predators and scavengers can quickly become immensely complex, especially when multiple species have shared a carcass, but understanding the behavior, feeding mechanics, and preferences of different species can allow you to untangle intricate stories of predation, scavenging and kleptoparasitism. The word “kleptoparasitism” refers to when one animal steals the food obtained/gathered/killed by another, and this ecological interaction plays a major role in shaping the feeding behaviors of different predators and scavengers. Now might be a good time to warn you that this article contains extremely graphic pictures of dead animals in various states of mutilation and decay, so if you would rather not see such things scroll no further.

Let’s start with the basics. Larger animals cause more significant damage to carcasses, and smaller animals cause less significant damage and leave more parts behind. This intuitive fact is apparent from prey items as small as sparrows to as large as elk. When a sharp-shinned hawk eats a varied thrush, the many body feathers must be removed as each small downy feather would be an awkward, non-nutritive mouthful for the small hawk, and thus when investigating the kill-site you will find nearly every single body feather neatly removed and piled on the ground. When a mountain lion eats a varied thrush, the small amount of meat on the bird is certainly not worth the time it would take to remove every single feather, and each individual feather does not represent nearly the same level of gastronomic hardship for the lion as it would for the sharp-shin, and in fact the lion will pretty much eat the bird whole, leaving behind a handful of flight feathers and whatever body feathers just happened to fall off as the bird was gobbled up.

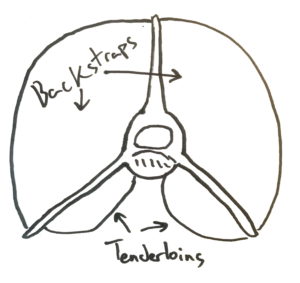

When a mountain lion feeds on a deer carcass, many of the largest bones in the body will be crunched and partially or entirely consumed, including vertebrae, femurs, pelvises, skulls and scapulae. When a collection of smaller scavengers such as foxes, fishers, skunks, bobcats, eagles and vultures feed on a deer carcass the majority of the bones and skeleton will remain intact, picked clean of meat. With just this basic knowledge in mind, examine the photos below of a deer carcass in northwestern Oregon, taken by Paul Glasser, and try to determine what has been feeding on it.

|

|

|---|---|

|

Photos by Paul C. Glasser

|

|

Notice that the posterior ribs have been chewed through, and some of them have been pried and bent out to odd angles. The hind legs have been picked clean, and the femurs, fibula and tibia are still articulated to the skeleton. The heart and lungs of the deer are uneaten, but the fleshy exterior of the rumen has been consumed almost entirely, leaving its inner contents exposed. The front right leg of the deer is entirely missing, but given that the articulation of the scapula to the ribs and vertebra is entirely muscular and not skeletal this is not surprising. Finally, the carcass has been left in the middle of the creek and the position of the animal is consistent with a natural dying pose, indicating that the carcass has not been drug or repositioned. All of the above are great indicators of the feeding of mesocarnivores such as foxes, bobcats, fishers, raccoons, skunks, etc., and are negative indicators of larger predators such as black bears, mountain lions, wolves and coyotes. This buck was hit by a car on a road nearby and limped off to die in this creek bed, and Paul placed a trail camera at the site after taking the above photos, which revealed first a bobcat and then a coyote feeding on the carcass. Let’s break this story down by the various body parts and organs of the deer and the feeding sign that they bear.

Digestive Organs: Bobcats and mountain lions are obligate carnivores, and both species tend to leave the digestive tracts of their herbivorous prey completely untouched, and sometimes they even remove these organs and cover them with debris a short distance away from the rest of the carcass. In the case above, the fact that the digestive organs have been opened and fed on suggests that some other omnivorous scavenger was at work before Paul”s camera captured the bobcat. Bears, coyotes and most omnivorous mesocarnivores will eat at least part of the rumen or intestines, and sometimes they will eat the entire tract and its semi-digested contents. Benjamin Kilham has observed black bears feeding directly on deer scat and speculates in his excellent book, “Among the Bears”, that this serves to inoculate their own guts with the bacteria upon which deer rely to digest plant matter, thereby increasing their own ability to educe nutritive energy from vegetation. It is possible that bears and omnivorous mesocarnivores derive a similar benefit from feeding directly on the stomach and intestines of ruminants. In short, bobcats, mountain lions and other obligate carnivores are very careful not to make a mess of the digestive tract and its contents, while more omnivorous species tend to show indifference and sometimes the opposite inclination.

Internal Organs (heart, liver, lung, kidney):