ON AIR: Steve Pavlik on the Thin Line Between Humans and Animals

An Audio Interview with Julie West, MLF Broadcaster

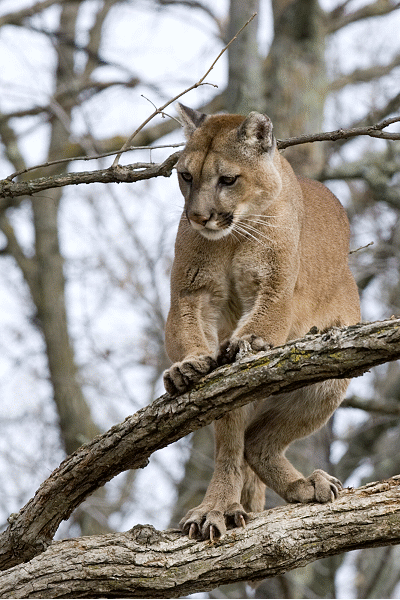

In this edition of our audio podcast ON AIR, Julie West interviews Native American Studies Teacher Steve Pavlik about the Native American view of mountain lions and other large carnivores. Mr. Pavlik discusses the field of cognitive ethology, explaining that animals have rational thoughts and emotions not unlike people. With a better understanding and respect for the mountain lion, Steve Pavlik believes we can promote a more humane treatment of all wildlife, as well as reform Fish and Game management agencies.

Listen Now!

Listen Now!

Listen to the interview from MLF’s ON AIR program, podcasting research and policy discussions about the issues that face the American lion.

Transcript of Interview

Intro: [music] Welcome to On Air with the Mountain Lion Foundation, broadcasting research and policy discussions to understand the issues that face the American lion.

Julie: Hello, my name is Julie West with the Mountain Lion Foundation. I look forward to speaking with today’s guest, Steve Pavlik. Steve teaches Native American studies and native science at Northwest Indian College in Bellingham, Washington, and has over 30 years of experience in American Indian education.

He holds masters degrees in both American Indian studies and in American history from the University of Arizona. Mr. Pavlik is the author of an upcoming book The Navajos and Animal People: Essays in American Indian Ethnozoology, and he’s edited two other books; A Good Cherokee, A Good anthropologist: Papers in Honor of Robert K. Thomas and Destroying Dogma: Vine Deloria, Jr. and His Influence on American Society.

He has also published over 60 other articles, essays, and reviews, and chapters in anthologies on mountain lions and on Mexican wolves. He has lectured and presented extensively in the field of Native American studies. His areas of academic specialization include Native American religions and spirituality, ethnozoology, cognitive ethnology, and environmental ethics.

Mr. Pavlik is a naturalist and an activist who has volunteered with numerous environmental organizations including Defenders of Wildlife, The Sierra Club, and The Sky Island Alliance. His special interest is large carnivore conservation, and he has been especially active in campaigning for the reform of wildlife management policy as it relates to carnivores. So welcome, Steve. Hello.

Steve: Great talking to you, Julie, and thank you for inviting me today.

Julie: Yes, and I’m really intrigued to speak with you for a number of reasons but some of my other guests have been wildlife scientists or maybe have come from a wildlife management background and so I look forward to speaking with you because you bring the academic scholarly perspective and also the Native American perspective which I think will shed light in a unique way on the subject of mountain lion ecology.

As a place of starting, your bio mentions that you’re engaged in cognitive ethology, and that’s a new term for me. I loved learning a little bit about it, but it’s the study of the emotional and behavioral lives of animals. I thought you could start by telling us about this area of academic specialization in your studies.

Steve: Sure. I’d be happy to. I guess in a nutshell people who consider themselves to be cognitive ethologists basically believe that animals are individuals, that they possess rational thought, that they possess rational conscious thought, including self-consciousness, that they’re sort of blessed with a rich range of emotions very similar to what you or I might possess.

I can’t speak for all people who identify themselves as being cognitive ethologists, but for me, I think wildlife management talks too much – particularly when it comes to carnivores – about instinct. The topic today, of course, is mountain lions, that mountain lions are unpredictable, that mountain lions act strictly on instinct and so consequently you treat them in that respect. Where as somebody from my perspective, you consider mountain lions to be thinking – well from a Native American standpoint, certainly – thinking beings just like you or myself.

Julie: Yes. Interesting. You had also motioned this is kind of a brave new world, and I don’t know how long ago that statement was made, but is that true? Is cognitive ethology a relatively new branch of animal behavior science?

Steve: You know, it really is. Its origins are old, and if you go back in time in to the 1870s, no-less a scientist than Charles Darwin wrote a book on animal emotions, and he described emotional views of animals in his book. But then, for the next hundred years or so the field sort of languished. Nobody was really doing much of anything.

Finally, we have a few scholars who popped up like Donald Griffin and Marc Bekoff and some others who in recent years have been doing really a lot of writing in that field. Often times the research in cognitive ethology deals with domesticated animals or sometimes it deals with the so-called higher animals like whales and dolphins and primates. My interest though is carnivores.

Julie: Do you think that an orientation toward cognitive ethology, especially as it might become part of the mainstream dialog, could potentially begin to influence policy and some of the wildlife management practice with that as the backbone?

Steve: I definitely believe it can and sort of – well jumping a little bit ahead, I teach at Northwest Indian College as you mentioned, and we’re a tribal college up in Washington State. Our student body is almost totally Native American, and we have the country’s only four-year Bachelor of Science degree in native environmental education. It’s our goal to produce tribal wildlife managers who perhaps see things differently than mainstream wildlife managers.

In fact, right now I’ve developed a class which I plan on teaching in the fall on indigenous cognitive ethology because I think that Native Americans have always been cognitive ethologists. They’ve always believed that animals can think, that animals are conscience, that animals have emotions. So it has to begin somewhere, and I’m hoping that it will begin with the Native American tribes in this country.

Julie: Yes, and hopefully those voices can become part of the dominate culture’s way of dealing with animals as well.

Steve: I really hope so.

Julie: This may be an interesting segue as well then. In many indigenous ancestral stories, the boundaries between the human and nonhuman worlds, which include animals, were often blurred. I’ve been fascinated by tales of transformation or shape shifting where a man might marry a woman who’s really a bear or a mountain lion for example and then spend part of the year with her animal family, and I love these stories.

I see them as stewarding strategies because if you’re related, you presumably won’t exterminate a species but you’ll safeguard its survival. I thought you could speak to some of these perspectives as they’re understood in your work with Native American communities.

Steve: You’re correct about Native American thought versus western thought. If you look at mainstream societies – Judea-Christian background – the Christian creation stories, so to speak, tells us that man was created first and that man was created in gods image, that animals came to be created later on, that man was given the power to name animals. He was given dominion over animals. Consequently most people in western society have just been brought up with the attitude that it’s a separate creation. It’s just two different – there’s us and there’s sort of them.

Whereas in Native American culture, if you look at many of the creation stories, man really wasn’t created first. It was the animals who came before man and then man sort of came – this is not true will all tribes but with most tribes I’m familiar with – man was created later on. Consequently there was no idea of dominion over the animals. In fact most tribes talk of the time when man and the animals and even the deities could walk together, talk together. They lived and communicated with each other and so there was – you used the word blurring, and I think that’s probably a good a term as any.

But I think there was a very thin line between humans and the animal world, and the thinner that line is, the easier that line, I think, is to cross. In many of these stories, animals had that power of transformation. In many native stories you have accounts of humans marrying animals and so on and back and forth and children who were part animal and part human. In that way of thinking of things if you – there’s a big difference between looking at a mountain lion and seeing him as just simply an animal, perhaps a resource, more likely a problem or a nuisance, as apposed to looking at a mountain lion an seeing him as a relative.

Julie: That’s a nice way of putting it.

Steve: It’s a big difference.

Julie: Yes. We’re all related. I wonder how people can hold that thought as they are concerned about coexisting with animals such as predators like cougars. I know that cougars are elusive creatures who aren’t likely to strike out at a human or kill a human but there does seem to be this fear that really triggers people. How can we coexist with large predators?

Steve: I think part of dealing with any other being whether it is human or its one of what Navajos refer to as being the animal people, I think any relationship has to begin with respect. In the past, we just simply haven’t shown much respect to animals like lions and particularly carnivores and predators. We teach our children to fear them.

I was thinking when I was a kid growing up, I used to watch Wild Kingdom and different animal programs on TV. I just watched them constantly. But today when you turn on the television, whether you’re watching Animal Planet or The Discovery Channel or whatever, they tend to be more – it’s like animal programming on TV has entered into a phase of reality TV or their version of reality. You’re more likely to see something like When Animals Attack or When Animals Go Wild or The Top Ten Animal Attacks or something like that. I think it’s just really up to us to teach our children that there is a different side of these animals and it begins with respecting them

Julie: And also, in so many instances, people are encroaching on wildlife habitat. They’re choosing to live in these pristine, beautiful areas where their home is maybe right where animals need to access the waterways or large tracts of land. It’s no surprise when predators wander through your property. Again, how can people practically coexist if they’re choosing to live in these places where there are likely to be animals?

Steve: Well, that’s another thing. We hear from pretty much every game and fish department that mountain lion populations are exploding all over the country. It’s like everywhere you look, there’re mountain lions. I guess I am one of those people who believe, if anything, that mountain lion populations are probably in decline in this country.

I think you’re probably seeing more lions because their habitat is shrinking, and we are pushing them out of their territory, and we’re forcing them to come down into our towns.

The other thing, of course, is we create our towns as gardens where deer come in and feed, and of course the mountain lion follows the game. I think back to a Navajo view of things. Navajos say that when you see an animal that is sort of out of place or he’s in a place or location where you normally do not see him, then what is happening is that animal is trying to reach out to you, that animal is trying to send you a message.

I think that these lions that are coming into these urban areas are trying to send us a message and that message is that we have to stop destroying their habitat and stop pushing them out of their habitat. I think it’s time we listen to the animals who are trying to speak to us.

Julie: And you’ve written about the jaguar too, haven’t you? And its historic range in the Americas, especially the recent case concerning Macho B, the jaguar who was killed. Maybe you could speak to that.

Steve: It does point out – for your audience who may not be familiar with the story, the American southwest has historically been home to jaguars for forever. In recent years, like so many other animals, we’ve hunted them, we’ve pushed them out of their range and there’re only a handful of jaguars left in the entire American southwest.

A number of years ago they photographed a jaguar who they then went on to call Macho B. This jaguar for a period of almost 12 years was photographed with remote cameras in a particular mountain range in southeastern Arizona. But the entire time, Arizona Game and Fish Department was bent on capturing this animal, putting a radio color on him, and tracking him, even when he became an elderly cat.

To make a long story short, because it is a long story, eventually they did catch him and they injected him with drugs to put him to sleep and then they put a collar on his neck and he wandered off up onto a rock ledge and he never really moved again. They had to come in a week later and because he was so weak, at that point they could just basically pick him up and they had to bring him in and they wound up euthanizing him. It was a tragic story that angered a lot of people because it was a classic example of mismanagement of wildlife in this country.

It also goes into what we are talking about today. From a Native American perspective, you don’t have to put a radio collar on that animal to track them and learn every nuance of his life. You know that jaguar was out there, he was out there for perhaps 16, 18, perhaps 20 years, and he was a mystery to people. But there are some mysteries that we’re not meant to know. There are some mysteries that we are not entitled to know.

But western society has an attitude that’s contrary to that and so we wound up killing this magnificent animal who might very well be the last jaguar in the American southwest. And when you figure that we’re putting up the boarder fence between the United States and Mexico, which would preclude any other future jaguar from coming up from Mexico, those are the things that we bring upon ourselves

Julie: Right. And I know collaring is such a hard one even for me. I get, on the one hand, that the collars are giving you vital information about their migratory routes and maybe that you could use that information to better advise game and fish departments or even transportation, how we think about our infrastructure and where we make our bridges and highways. But on the other hand, as you say, they’re are doing just fine out there.

Steve: It’s a scientific tool, but you really wonder how much you can learn from a population of one animal.

Julie: Um, hm. Now you’ve worked with some other cougar biologists. I know Harley Shaw is one cougar biologist you have worked with. Maybe you could just talk about some of the things you did with Dr. Shaw and anyone else you want to group in that category.

Steve: I’ve known Harley for many years now. In addition to the work I do with tribes and the Native American aspect of mountain lion conservation, I also – I’m certainly not a scientist. If anything, I guess I would classify myself as a naturalist in that area.

But many years ago, Harley got a mountain lion study going in the Huachuca Mountains in southeastern Arizona. It was a study that was very – it basically was a track count survey, and for almost – I may be wrong on the dates, but – I think for almost a 20 year period, Harley, and the people who followed after Harley, ran these track counts in Huachuca Mountains for this period of time recorded where the mountain lions were, and so on, and that’s how I got to meet Harley. I worked on that track count for many years myself. So did other people.

Julie: So you were just tracking them and that’s maybe different way of understanding their range instead of just collaring them or actually trapping them the old fashion way

Steve: And I think increasingly, people are starting to move toward less intrusive means of studying wildlife. That idea of radio collaring and so on and so forth – I think we pretty much learned all we can learn about basic mountain lion behavior through radio collars and tracking. I think it’s just a matter of keeping track of animals, keeping track of these animals when they come into urban areas and so on. I think those are things that we need to know.

Julie: I know you have been critical of Arizona Game and Fish. It does seem like game and fish departments are often in a front line position to – as first responders – to orchestrate the strategies that will ultimately affect that lion’s future. And I wonder if you could talk about some of the more successful strategies you know of – translocation for example of an animal – there might be other examples and maybe some of the worst case examples as well.

Steve: I think game and fish – I know a lot of people within various game and fish departments, and I think the vast majority of people who I’ve met and worked with are certainly good people. I mean they don’t get into wildlife management because they hate animals or something like that.

In many cases I think they are limited to some of the things that they do. I know that in Arizona Game and Fish, for example, one animal that I have done research on for many years – I’ve done a lot of black bear research over the years and there was a there was a case back in the 1980s I believe, where there was a young woman who was mauled by a black bear up in the Catalina Mountains in Arizona. And she sued Arizona Game and Fish for two and a half million dollars and got it.

Julie: Oh, my.

Steve: She received that money. And from that moment on, there was a marked difference in the way Game and Fish dealt with moving animals from one place to another. My work with bears showed that up until that event, 80% of the “problem bears” that they trapped, they relocated elsewhere. After that event, 80% of the problem bears, they euthanized. You could see that sharp line when they changed their policy.

And I think that Game and Fish departments are very reluctant, very scared of being sued by the public and that’s a very real concern. A lot of times I think, for example, they exaggerate the dangers of mountain lions and bears just to keep the distance between mountain lions and bears and humans, and I think that is sort of unfortunate.

At the end of the day, though, game and fish departments primarily serve two masters: one are the land owners and the second ones are the hunters. They want to keep the land owners happy so they can keep the land open for hunting and that’s where they get their money from.

I think that mountain lions and predators are up against a stacked deck. They’re viewed a being competitors and viewed as being public dangers, so we tend to manage carnivores very badly.

Julie: Seems like we need those creation stories to be part of our collective thinking again, but it seems like that’s a slow transition.

Steve: It is.

Julie: I had a friend that told me about visiting Indonesia. One of the parks in Indonesia was closed on certain days of the week presumably because the monkey gods would be angered if you came into the park. I loved thinking on that as a national park strategy to give the land a break, (laugh) to give the creatures in the park a break by again reviving or putting the myth story out there. It’s folkloric yet it’s practical because the park gets a break.

Steve: Well, I think those are the things we really need to do. I think one of the things that we also need to move to, and I don’t think that the political winds in this country are favorable, especially now towards that, is granting legal rights to the natural world.

Unfortunately you can move into an area and poison the water and clear cut the forest and fence up an entire area for cattle or whatever the case may be and the animals that are in there have to simply move on or become exterminated.

Julie: Right. They’re a by-product of that larger process.

Steve: And that’s one of the things I like to do when I’m working with tribes because if there were any people on this continent who one would hope would be most receptive to the idea of – and what I’m really talking about here is constitutionally guaranteeing rights for the natural world and the wildlife – it would be the tribes to whom it was always a natural part of their heritage

Julie: Can you give a hint, then, of your upcoming book The Navajos and Animal People: Essays in American Indian Ethnozoology and maybe tell us something we can look forward to in reading this book

Steve: Sure. The book started out actually – it was a product many years in the making. One of my professors at the University of Arizona was the famous Sioux scholar, Vine Deloria, Jr. Vine one time invited me to sit on a panel on Native American religion at a conference that we were attending and I told him at the time I said, “Vine, I really don’t know that much about religion.” He said, “Well you know about Navajos. You know about animals. So why don’t you do a presentation on Navajos and animals?” So I said ok.

I wound up presenting a paper on the Navajo relationship to bears and that was very well received. So the next year, on that same panel, I wound up doing a paper on, I think, Navajos and wolves, and the next year it was coyotes, and the next year it was jaguars, and the next year it was snakes, (laughing) and so over a period of time I wound up presenting about 10 of these papers. I don’t know if I did this consciously, but I realized that all these animals that I had been writing on were predators, carnivores.

At any rate, people have been talking to me over the years about cleaning up these articles, putting them together, and coming up with a book. That’s kind of the genesis of the book. There’s this chapter in there on bears, one on mountain lions one on wolves, coyotes, jaguars, snakes, eagles, and another concluding chapter on smaller predators as well.

Julie: Talk about the chapter on mountain lions a little bit. Do you get into some of the actual Navajo ceremonies that are related to the Mountain Lion as a sacred cat?

Steve: Yes, ceremonialism is obviously a part of that. There’s so much to tell. In the beginning when people emerged, Mountain Lion was one of the original deities that were there. There was a Mountain Lion in capital letters, capital “M,” capital “L,” who was very much like the Navajos would be.

I would be tempted to say the Navajos viewed mountain lions and bears and other animals anthropomorphically, but at the same time that’s sort of a human way of looking at things.

In other words at the beginning, all the beings sort of had a shape and a lot of times when Navajos tell these stories and they imagine these animals in another time like in a creation story in the time before time, so to speak, they’re in the shape of human beings.

Mountain Lion in the early stories is one of the most important of the Navajo deities. He’s one of the leaders of the Navajos, of all the animal people. He’s always been admired because of His strength and His courage, His stealth and His speed, and His intelligence and so on. So Mountain Lion at the very beginning was seen as being one of the important deities. Later on as the Navajo stories go on, and as the Navajos came to be as a people, Mountain Lion was also assigned to be a protector for one of the major Navajo clans. In this role, Mountain Lion sort of protected the people against enemies.

There was the story of how the Navajo were attacked at one point by an enemy which some anthropologists believe were probably the Ute Indians. After the Navajos had been beaten up very badly by the Ute, they asked for the Mountain Lion’s help, and he attacked the Ute and tore them up and protected his people. At that point there was concern that now that Mountain Lion had tasted human blood, so to speak, that could we ever fully trust him again. At that point, he was told he needed to live apart from the people, and he went up into the mountains, and he became the mountain lion as we know today. So that was kind of the origin of mountain lions.

Julie: Have you seen a mountain lion or had any experiences with mountain lions that you would like to share?

Steve: You know I am one of those people who really have not been blessed with seeing a mountain lion in the wild. I have done a lot of mountain lion tracking over the years and there’ve been literally times when I have gone up a trail with fresh snow on it, gone up to the top of the mountain, started back down the trail and found mountain lion tracks on top of my tracks.

Julie: Oh, my. (laughs).

Steve: Because mountain lions are sort of like – they’re cats and are very curious and they do like following people. They do like observing people and I think that there is probably a lot you can say about. They mean you no harm, no malice but they’re just sort of curious. That’s always a wonderful experience when you know that you have one on these animals who is out there following you around (laughs).

Julie: Well, we need to close soon and this is maybe closing on a broad note, but I watched a lecture by your friend and colleague, Dan Wildcat, Power and Place: Indian Education in America, and he talks about the difference – and he admits that this is a very crude distinction – between western philosophy and indigenousness philosophy; western philosophy having more of an obsession to organized the world into categories, break things down into discreet areas and indigenous philosophy really having to do with observing relationships and processes that humans are just in the middle of and living in the world so its more relational oriented.

I have noticed a trend, at least in academia, towards interdisciplinary studies where boundaries between disciplines might be blurred in favor of learning something outside your area of expertise. In that regard, I don’t know if this is a temporary trend or if this is a slow cycle, a long slow cycle back to some of the indigenous thinking that’s guided humans for so long on the planet. I just wondered if you had any thoughts on that or if you see that trend as hopeful or if you notice it yourself?

Steve: Several things come to mind. I think that when you look at what we humans are doing to the planet, whether it’s poisoning the air or poisoning the water, clear cutting the forest or driving species of animals into extinction, it’s obvious that we have to change and we have to look at nature in a different way.

I think part of it goes back to – and this is one of the things that certainly Dan talked about in that lecture that you heard – the idea that where you see yourself in comparison with the rest of the natural world.

People like to say, for example, when talking about Indians, they sort of talk about Indians in almost in a romantic sort of way, they say that Indians worship nature, that they love nature, are close to nature or something like that. But in reality the best way to look at it that Indians were a part of the natural world. They were an intrigral and intimate part of the natural world and it was all about relationships.

Ecology is a relatively new field for western society, but native people have been ecologists since the beginning of time, and that idea of having a relationship with the natural world, it has to be a relationship where you not only take, which we as western people are very good at doing, but it has to be a relationship in which we give back as well.

Native American relationship with the rest of the earth was reciprocal. You played a part in it. You perhaps hunted a deer. You took a deer’s life for food, but at the same time you offered the right prayers and the right ceremonies.

One of the things you talked about a moment ago in the case of Indonesia, there were times when tribes would go into the mountains and just pray for the well being of that mountain, the health and well being of that mountain and all the animals that were there. There was – and I think of the Lakota in the Black hills. They set aside the month of June as a time when they took care of the mountain. They helped the mountain heal and we don’t look at things that way. We just continue to take.

Our relationship to the natural world is not an appropriate relationship in that respect and whereas the native relationship to the natural world was appropriate. It was reciprocal, it was appropriate, and you have to do those things

Julie: And I wonder if we’ll get back to that, maybe by dire consequence because we have to or – I’ll be curious to know because I am a glass half full person, what will be the markers in our path that will lead us back to that place of reverence and respect and reciprocity. Surely your work as an educator is one of those markers and other colleagues of yours and folks at the Mountain Lion Foundation being another one. So thank you for the work you do, Steve, and thank you for the interview today.

Steve: Well, thank you very much. I enjoyed it.

Julie: Yes, all right. Take care.

Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for noncommercial use.

MORE ABOUT STEVE PAVLIK

Steve Pavlik teaches Native American studies and Native science at Northwest Indian College in Bellingham, Washington and has over thirty years of experience in American Indian education. His areas of academic specialization include Native American religion and spirituality, ethnozoology, cognitive ethology, and environmental ethics. He has published over sixty articles, essays, and reviews, including chapters in anthologies on mountain lions and on Mexican wolves. He has also lectured and presented extensively in the field of Native American studies.

Mr. Pavlik is a naturalist and activist who has volunteered with numerous environmental organizations including Defenders of Wildlife, the Sierra Club, and the Sky Island Alliance. His special interest is large carnivore conservation, and he has been especially active in campaigning for the reform of wildlife management policy as it relates to carnivores. For more background information about Steve Pavlik, visit his Ghost Bear Blog: a website dedicated to indigenous views of the natural world.

The Mountain Lion Foundation debunks an old internet hoax.

The Mountain Lion Foundation debunks an old internet hoax.