On Air with Marc Bekoff

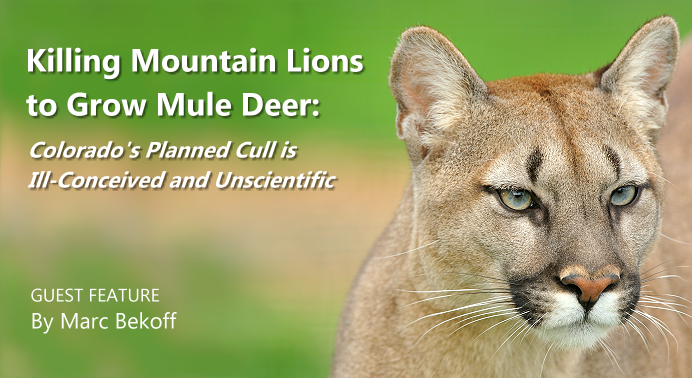

An Audio Interview with Julie West, MLF Broadcaster

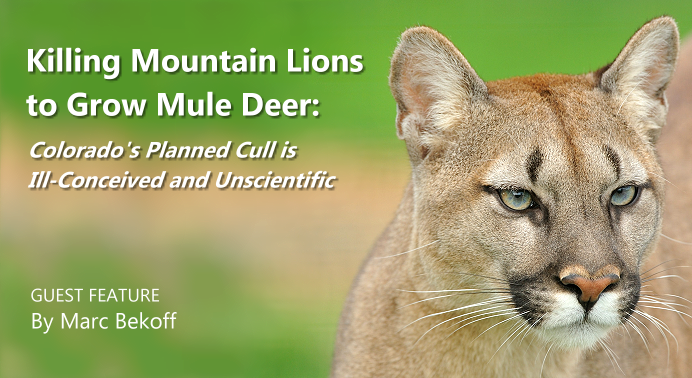

In this edition of our audio podcast ON AIR, MLF Volunteer Broadcaster Julie West interviews Marc Bekoff. Marc discusses Colorado’s unscientific plan to hunt more mountain lions in the hopes it will increase deer and elk herds. The conversation goes beyond wildlife management to take a deeper look at how we view, value and treat all other animals who share this planet. Perhaps it’s time we all stop and analyze the killing of animals from an ethical perspective.

Listen to the interview from MLF’s ON AIR program, podcasting research and policy discussions about the issues that face the American lion.

Transcript of Interview

Intro: [music] Welcome to On Air with the Mountain Lion Foundation, broadcasting research and policy discussions to understand the issues that face the American lion.

Julie: Welcome to On Air. I’m Julie West, your host, here today with Marc Bekoff. Marc is a former Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado at Boulder, and co-founder with Jane Goodall of Ethologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. Marc’s main areas of research include animal behavior, cognitive ethology, which is the study of animal minds, behavioral ecology, and compassionate conservation. He has won many awards for his scientific research including the Exemplar Award from the Animal Behavior Society, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. Marc has published more than 1000 essays, 30 books, and has edited three encyclopedias. His books include, Ignoring Nature No More: The Case For Compassionate Conservation and Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence. His latest book, The Jane Effect: Celebrating Jane Goodall (edited with Dale Peterson) was published in February 2015. You can learn more about Marc by visiting his homepage: marcbekoff.com and with Jane Goodall. The address is http://www.ethologicalethics.org/.

Welcome to On Air, Marc, hello!

Marc: Hello. I’m glad to be here.

Julie: Great, great. Now Marc, you are also a contributing blogger for the Huffington Post, and you use that forum to reflect on a range of topics about animals and humans’ relationships to animals, from the controversial killings of Cecil the Lion and Blaze the Bear to scientific developments regarding the emotional intelligence of animals. What prompts you to choose the stories you write about, and is there a common denominator?

Marc: Well . . . yeah. I guess there are a lot of common denominators. I’m really interested in what I call animal cognition, animal smarts, if you will, animal emotions and compassionate conservation and wrapping that into a very strong view on animal protection. So, generally the essays I write for Huffington Post, I also do regularly for Psychology Today, reflect either new empirical research in those areas, or problems that we’re having, like advocating killing mountain lions to save deer, or killing cormorants to save salmon in Oregon, or I wrote about Cecil the African lion who was killed. So, there are motivators, I think, by trying to improve human-animal relationships, especially in the wild.

Julie: Yes, and you live in a beautiful wild place. You live in mountain lion country there in Boulder, Colorado, and one of your recent blogs cuts close to home. You write that Colorado Parks and Wildlife has proposed a scheme to kill mountain lions in order to protect and grow mule deer populations. You and other critics say this idea is ill conceived and unscientific. What rationale is being used to support this proposal, and why is it wrong?

Marc: Once again, there are lots of sides to this issue. But it’s wrong for a number of reasons. It’s wrong because the empirical data show that in other studies killing lions to save deer hasn’t work. Last year there was this publication of a paper that included the slaughter, and, really, I mean the brutal slaughter of 875 or so wolves in Canada to save rangeland caribou, and it didn’t work. So basically, you know, the scientific data don’t support killing one species to save another. The massive slaughter of wolves in Alberta, Canada was done, supposedly, to save rangeland caribou, but it didn’t work. There are also ethical questions. You’re going to kill lions to grow mule deer to be killed by human hunters. I mean, it’s . . . in my view it’s wrong on a whole lot of different levels.

Julie: It’s like a chain reaction of killing. You know, you talk about this chain reaction of disruption happening in the wake of trophy hunting affecting, for example, the cubs, because new males will move in and oftentimes kill the cubs sired from the males that were killed, and female lions will often get killed protecting those cubs, so it really seems like it’s a chain reaction of death.

Marc: Yeah, exactly, that’s a good way to look at it. And from an ethical point of view, we just can’t go around killing animals. Number one, we can’t just kill animals, and these are really experiments. And I use that word, because they are experiments. They want to say that, if killing the lions results in more deer, for example, for hunters to kill, then there are more deer out there for hunters to kill, which generates more money for Colorado Parks and Wildlife. So, yeah.

Julie: I think about New Englanders who are probably wishing they had some mountain lions to deal with their deer population; it seems very ironic that Coloradoans would resort to this.

Marc: Well . . . it is, and it isn’t. I believe it’s generated by a need for money — hunting and fishing licenses, for example, generate a lot of money. So if you don’t have enough deer out there, or game, as they call them, then people may not be able to buy the same number of enough licenses. So what strikes me in this case, is that the scientific data do not support that killing mountain lions will grow mule deer. Yet Colorado Parks and Wildlife still wants to do it. And let’s be clear, even if there were data that supported it, it still would be ethically wrong. In other words, you can’t argue that, “Well, we know that killing more lions will produce more deer.” That’s just a lame argument, and it becomes, if you will, lamer, and it becomes a lot more difficult to support when you can say, “Well, we’re going to save the deer only to killed by humans.”

Julie: What do they need in order to push this through, and how seriously is this proposal being taken?

Marc: Well, we don’t know. There are public hearings, and as I wrote, the Humane Society of the U.S. is trying to get Colorado Parks and Wildlife to have a hearing in Denver, but so far that’s not been scheduled. The next one at the end of November is in Ouray, Colorado. It seems like they’re very intent on it. It seems like they really want this proposal to go through so they can go kill the deer. I think they’re quite serious about it.

Julie: It almost seems like any excuse to hunt the mountain lions.

Marc: Exactly. Mountain lions get a really bad rap. They are predators. They are a prototype predator. They do kill other animals, and, on occasion, they kill humans. Carnivores get a bad rap in the public eye.

Julie: Everything I have learned about top predators is that they keep ecosystems in check.

Marc: Yeah, people get scared of them, though. I had three up close and personal interactions with mountain lions. I was within a couple of inches of mountain lions on three occasions, and I survived. There was nothing cool about it. When I tell people about them, they’ll go, “Oh, that’s really cool.” No, there was nothing cool about them, at all. I hope I never meet another mountain lion. But that doesn’t mean that, after my encounters when I lived in the mountains, that I wanted those lions to be killed. And, as I’ve said many times, if I had an injurious or fatal interaction with a mountain lion or another carnivore, I would not want that animal to be killed.

Julie: You mention that it’s a scheme to raise money as much as anything else, but at the end of the day, won’t they be weighing the science? And from what you’ve said in your article, the scientific research states that deer need habitat, food and space to move and forage without heavy persecution by hunters in order to thrive. So I would hope that some of the science would be weighed in the process of debate.

Marc: Yeah, I would, too. But I know from lots of legislation in other aspects of animal protection, you know . . . the use of animals in laboratories, they say, well, where’s the science, for example, that shows that mice and rats suffer — that they display empathy and have rich and deep emotions? The science is out there, but the people who write the legislation ignore it. So I don’t have a lot of faith. And people will dispute it. They’ll say, well, the studies were done in other states, or they’ll find a criticism of the study, and they’ll throw out the baby with the bath water. But the facts are, the science does not support it. And there’s also an ethical dimension, and when I’ve done other interviews, and when I’ve talked with people about this and other cases . . . and this is a change that we’re seeing now, currently.

People are more and more concerned with ethics, as well. In other words, if the science were, say, ambivalent, there are still people who would say, it’s wrong to kill the lions to save . . . to grow deer. It’s not to save the deer, so much, as to get rid of the lions. Growing them basically means having more of them. So, times are really changing for the better. And divisions of wildlife are going to have to factor that in — that public sentiment is changing. And a lot of the people who may have supported, basically this unwarranted slaughter of lions, will no longer support it. That’s why it’s crucial to have these public hearings to get a broad spectrum of the population, in this case, the stakeholders in Colorado, to weigh in.

Julie: Yes, and that’s why I was so heartened to see the role that social media took regarding Cecil the Lion and his death — that shame is a powerful tool, and the scarlet letter emblazoned on his forehead as a result of the social media messaging made me realize, huh, interesting; it seems like it’s helping to turn the tide in the way we view and treat animals.

Marc: It is. In fact I just wrote a blurb for a forthcoming book on mountain lions that will be out next spring. And the author points out the same thing. People I know — because of this current situation that’s pending in Colorado — there are people I know who were horrified to hear about Cecil and have either no opinion or think it’s just fine to kill lions in Colorado.

Julie: Hmmmm. That’s odd.

Marc: Right. And that brings out the question that comes out a lot. In fact, I just taught a course online for a class at Colorado College. And it was freshman. And one of the women in the class asked that very sort of question — why is it that we hate, if you will, or vilify some animals, and we love others. And I think the predator situation, or the fact that lions are predators, really scares people. They’re totally misunderstood. And people think that mountain lion attacks occur every day. They don’t. That’s not to say that when they do occur that it can be tragic. They are. It’s like this bear who was recently killed up in Yellowstone, Blaze. And her killing left her two cubs alive. Blaze didn’t do anything, and I don’t mean that in a light sort of way. Blaze didn’t do anything. And it was a tragedy that a human got killed, but it was a human who had trespassed into Blaze’s territory if you will.

Julie: Right. What can humans do to be more accountable?

Marc: Yes. They have to be more accountable. We have to take more responsibility. And when I lived in the mountains outside of Boulder (Colorado) among lions and coyotes and bobcats and black bears, I made it very clear to my neighbors — and I wasn’t, once again, being facetious — if something happened to me, don’t kill the animals. We need to take responsibility. The other thing, of course, Julie, is that there are too many humans, and we are expanding all over the place, which means that we’re going to have more and more conflicts with other animals. And that’s why this study sets a horrible precedent, because people can say, “Well, Colorado did this, why don’t we do it?” You know what I mean? We need a paradigm shift. That’s the way I look at it.

Julie: Let’s back up for a minute, because you talk a lot about compassionate conservation. What is meant by compassionate conservation?

Marc: Well, compassionate conservation is basically a view that animals are not objects for us to exploit. And the two guiding principles for compassionate conservation are, first: Do no harm, which really means that, when we are interacting with other animals and trying to figure out how to peacefully coexist with them, we do not harm them. And the second is that individuals count — that we are concerned with the well being, if you will, of individual animals — not of ecosystems or populations or species. Applying it . . . you could be applying it to this proposed killing of lions in Colorado.

Compassionate conservation would argue against it because the mandate is first, do no harm, and the second is individuals count, which means that every individual lion counts, and you have got the collateral damage of, perhaps, other lions, like cubs, dying, when the female is killed. So this is the perfect example — although it’s not necessarily a conservation issue, per say — it’s a perfect example where the basic tenants of compassionate conservation could be applied.

Julie: In your book, Ignoring Nature No More: The Call for Compassionate Conservation, you imply that exploitation of animals continues because our relationship to the natural world, itself, is framed by sociocultural-political and economic habits of exploitation. And you write about things people can do to expand their compassion footprint. What are the top habits of exploitation you would like to see changed? And how can more people get on board with compassionate conservation?

Marc: Right. Well I would like to see there be just a general agreement that we need to peacefully coexist with other animals; you could say including and especially the ones into whose homes we have moved, and I don’t mean that lightly. When I moved into the mountains, I knew there were lions and bears and other dangerous animals around, and I made that choice. I think what we need to do is accept the fact that we need accountability, and we need to take responsibility. And I think the paradigm shift would be to say, look, we moved into their homes. There are too many humans. We are spreading out all over the place. And we just can’t move into their homes and then decide that when they become a “problem,” that we’re going to kill them. And I think . . . I already know some people who are really beginning to accept that — to say, OK, if I’m going to choose to live in the mountains, or I’m going to hike where there are other animals, I need to take care and accept the fact that there are risks.

And I, personally, had to change my habits when there were mountain lions around. I had to change my habits in terms of when I would go out with my dogs, when I would ride up and down my dirt road, because, number one . . . of course, I didn’t want to get attacked by one of these animals, and, number two, I knew they were there, and I loved knowing they were there.

So the other thing I would like to see is this deeper reconnection with nature. That’s what I call the rewilding — the personal rewilding, where people really reconnect. Not like, “Oh, I’m going to go into the mountains, and I’m going to spend the day there, and the bottom line is, if an animal bothers me, I’m going to report it, and that animal is going to get killed.” And I’m not being facetious. That happens. The personal rewilding means reconnecting with nature — appreciating nature, if you will, as it is. And the other aspect of rewilding — and I can’t emphasize this too much — is accepting responsibility for what we do. If I go hike and something happens to me, then it’s too bad; it’s tragic.

You know, this recent bear attack and death in Yellowstone, it’s a tragedy. Somebody said, “Oh you probably think that’s OK.” No, I don’t. And nobody working for animals thinks that’s OK. But the fact of the matter is — Blaze, in my opinion, should not have been killed, because there’s also no evidence that suggests that a bear who kills once is likely to kill again. So it’s a big paradigm shift that includes rewilding in the personal sense, and accepting the fact that these animals have the right to live the lives they’ve evolved to live, and if we’re going to intrude in their lives, that there are attendant risks for which we need to be responsible.

Julie: Yes, the animal should not be penalized for doing what’s in its nature for protecting its cubs. Or, as you say, you’ve just built your home adjacent to a migratory corridor, so keep your pets in at night. Or, know where you are, and alter your habits accordingly. Yeah, it’s a reciprocal relationship. Call it being good neighbors, I guess.

Marc: Yeah! Exactly! I like that! It’s called being good neighbors. It’s accepting responsibility, and it’s exactly what we ask of people in other aspects of life. I’ve often suggested to realtors around Boulder that when they show a house, they explain to the potential buyers that there are animals such as lions and bears around, so that they know this. I don’t know about you, but I know a number of situations where people have literally moved into an area and have moved out soon after because they didn’t want to live — either because they have kids — with dangerous animals. So rather than advocate for killing them, they moved out.

Julie: Right, right. Interesting. Now, you’ve connected with conservationists around the world and have traveled widely. Does any one country emerge as having the best overall record for compassionate conservation?

Marc: No, I think it’s too early in its growth, if you will. But there are phenomenal projects — one that was completed — I wrote about it in earlier Huffington posts and a Psychology Today essay – in India. India has a number of projects going that really are smack central, if you will, in terms of the tenants of compassionate conservation. The other thing about compassionate conservation is that it takes into account all stakeholders. So it takes into account the interests of the humans and the non-humans, and the community.

There’s a great project that was concerned with dancing bears in India, which is a very long cultural tradition. And the way they solved it and got the people — people were doing it for money, it wasn’t like they hated the bears — so over the years they showed them how to have alternative modes of income, including the women and the men. So basically, they put an end to the dancing bears. And that’s it. That’s just a perfect example of the scope of compassionate conservation taking into account the interests of the non-humans, the humans and the community.

And there’s another project where there are tigers who kill humans. And they realize that instead of talking about the problem animals, they started talking about problem locations and got people to avoid the locations at certain times. And it was just the flip in the vernacular, if you will, talking about — this is a problem location rather than this is a problem animal. And, you know, humans are very sensitive to the use of words, and the people who did this study agreed that just changing from “problem animal” to “problem location” helped to solve the problem.

Julie: Yes, that’s so true. And, again, it comes back to accountability, because knowing I live in a high problem area, whether it’s India or the mountains of Colorado — what can I do to adapt my patterns accordingly. So, like, in India, maybe you don’t throw trash outside your home, which will attract the stray dogs, which will attract the leopards and tigers. Or, don’t collect wood in the forest — basic things people can do to modify their habits. And also it’s interesting you mention India, because I feel like the Vedas, themselves — that ancient body of knowledge, itself carries messages of compassionate conservation through the teachings.

Marc: Yeah, absolutely!

Julie: Well, you co-edited the book, Listening to Cougar, with Cara Blessley Lowe, and with a forward written by Jane Goodall. This is a collection of essays about cougar ecology and people’s encounters with the big cats, and you shared some of your encounters. Did you learn anything new about the mountain lion through some of these stories?

Marc: I learned how much people are so interested in mountain lions, not only from the scientific point of view, but the role they play in mythology, in Native American literature, in the arts … Yeah, I learned a lot. You know, doing that book . . . I still see essays written by poets, writers, people who are naturalist, scientists, artists . . . is just the magnificence of the mountain lion, the cougar. I’m hoping that that widespread interest will help protect these animals.

Julie: Because they are . . . there is such intrigue. It’s a shame that in our news, what makes front page are these tragic stories. Wouldn’t it be interesting if our journalists and our papers were full of these inspiring stories about how we could actually reach out across our biological boundaries and understand each other, you know? (

Marc: Yeah! It would be wonderful if that were freed from the scientific journals and actually became more part of popular culture.

Marc: Absolutely, and that’s why I was saying that getting people interested in animals such as cougars, mountain lions, grizzlies, elephants . . . any animal. Getting them interested . . . you know, the lay population — non-researchers, artists, people in the humanities, writers — is really the way forward to grant more protection and get more respect for these animals, yeah.

Julie: Now you have partnered with Jane Goodall to create Ethologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. Has this effort made traction in field research and animal laboratories? And maybe you could give some examples if you know it’s made a difference.

Marc: Yeah, it’s made a difference in terms of field research, if you will, trapping and marking methods — making sure they’re humane. And the big thing is that they don’t change the data. We know that when you start handling wild animals, you can affect their behavior, and you can change their behavior, which affects the reliability of the data you collect. So, yeah. I get lots of emails of people saying — I’d like to mark animals this way . . . and in many ways, it sets a preface for compassionate conservation. Jane and I, both together and separately, have been writing about the importance of individual animals for years. When I looked at the description of Ethologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, which was put out 14-15 years ago, it really parallels a lot of what compassionate conservation is all about, and that is using humane methods, first do no harm, and the importance of individual animals.

Julie: Well, in thinking on cognitive ethology, are there any latest developments you wish to highlight, or any new information about what we’re learning about the way animals feel and think?

Marc: Oh, yeah. It seems that every day I’m getting something new about animal cognition and animal emotions. A lot of what we’re getting is people who are studying food animals — that cows are very emotional . . . pigs are empathic. We’ve got some really great data coming in on birds predicting the future, existence of certain foods, planning their meals for the future. And there’s a lot of stuff coming in on fish — showing how, in fact they are very emotional beings . . . Let’s put it this way, the data that is coming in do not counter what we have “thought” about these animals. The scientific data support.

Julie: I think the challenge is — you have this information, but then how can you reach out across the aisle and convince the big cat trophy hunter to care? If you had three minutes to chat with a big cat trophy hunter, what would you say? What would you say to change that person’s mind?

Marc: I would just explain to them that they are killing animals who have deep emotional lives; that they’re killing animals that have families, and if they kill one animal, they kill another animal. And I would just try to have a rational discussion with them of why killing animals as trophies is just wrong. My take on it — and I would rather talk to people who are not . . . when I’m not preaching to the converted — my take on it, in all honesty, is we need to keep putting this information out there and hope people grab onto it. So I’ve talked to some people who have given up hunting, not immediately, but based on sentience, based on taking the life of an emotional being — taking the life of an animal when there might be collateral damage. We just need to keep putting it out there, that’s what we need to do. Unwaveringly.

Don’t say, Oh, that’s OK if you only killed two lions or if you only killed two bears. No, it’s not OK. Killing mountain lions does not save mule deer. Killing mountain lions, killing grizzlies, killing wolves is wrong, for hanging them on your wall or getting rid of them because they are pests. I try to talk to them about what we really know about the behavior of these animals. That . . . they are very . . . some people just say . . . somebody was saying to me, well, wolves attack people every day. No they don’t. There have only been two known attacks in North America. So I just put it out there. I’m nice to them. I invite them to talk, as long as they respect me, and I respect them, and move on.

Julie: So, Marc, how can people get involved, for those fellow Coloradoans who might be listening. Is there a way they can lend their voice before it goes to vote?

Marc: I have a link on my article, and they’ll see where the next hearing is. They can write letters directly to Colorado Parks and Wildlife. The address . . . they can email them or call them or write letters. All that information is on the website of the Colorado Parks and Wildlife. They can try and go to the hearing in Ouray. They can request, as is the Humane Society of the U.S., having the hearing in Denver. And put a lot of pressure on them. That’s all they can do. Yeah. That’s what I think.

Julie: I see our time is about up, Marc. Is there anything else you would like to . . . a closing thought you would like to share with us? Or perhaps (share) one of your own encounters with a mountain lion?

Marc: Well, I appreciate your talking with me. As a closing thought, we can all do better in our interactions with other animals, and like I’ve said before, we have to respect them for who they are, not what they are, but for who they are, and take responsibility for our behavior. One of my encounters involved . . . I was yelling at a neighbor that there was a lion in the neighborhood and backing up, and my neighbor was kind of pointing frantically so I would look behind me. And I looked behind me just as I literally almost stepped into a mountain lion. I was a couple of inches away. So, of course, the first thing I did was, I ran. Because that’s what you do. I know you’re not supposed to run. But I ran as fast as I could up the hillside. And the lion just sat there. And it turned out he had killed a deer. He had eaten about 25 pounds of food. His stomach was almost hitting the ground.

Julie: (Laughs) Lucky you! He was already full!

Marc: Right, I was lucky! You know, it’s interesting to tell that story, but there was nothing funny about it. I mean I was literally a couple of inches away from that lion. And so . . . somebody had called it in. We were very firm with whoever came up — I don’t remember which agency came up — that they could not kill the lion. And they did not. They took the carcass away. The lion slept for two days on a rock and then disappeared. So having had three encounters like that, I feel that I can say with a lot of great voracity and enthusiasm: I loved meeting the lion. I never want to meet him again in that situation. I loved . . . afterwards . . . where I had that encounter I lived for another 25 years almost. I was very happy that there were lions around, and I changed the behavior of myself, and my dog.

Julie: Well that sounds like a happy ending to me. Sometimes I think that as much as we have a curiosity for seeing them, we give greater respect by just giving them their space and taking comfort in the knowledge that they’re out there in the wild doing their thing, hidden from man.

Marc: Yep. That’s exactly right. And, you know, like I said it’s a mix of science and ethics and, in my view, what’s right and wrong. And it’s definitely wrong to kill animals just to kill them.

Julie: Well Marc, thank you for your time today. And I encourage our listeners to read more about your ideas by visiting the Huffington Post and also Psychology Today. Thank you Marc.

Marc: Thank you very much, Julie. It’s my pleasure.

Closing: [music] This has been a Mountain Lion Foundation On Air broadcast. On Air is a copyrighted production of the Mountain Lion Foundation. Permission to rebroadcast is granted for noncommercial use. For more information visit mountainlion.org.

MORE ABOUT MARC BEKOFF

Marc Bekoff, Ph.D., is a former Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and co-founder with Jane Goodall of Ethologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. Marc’s main areas of research include animal behavior, cognitive ethology, which is the study of animal minds, behavioral ecology, and compassionate conservation. He has won many awards for his scientific research including the Exemplar Award from the Animal Behavior Society and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Marc has published more than 1000 essays (popular, scientific, and book chapters), 30 books, and has edited three encyclopedias. His books include the Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare, The Ten Trusts (with Jane Goodall), the Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior, the Encyclopedia of Human-Animal Relationships, Minding Animals, Animal Passions and Beastly Virtues: Reflections on Redecorating Nature, The Emotional Lives of Animals, Animals Matter, Animals at Play: Rules of the Game (a children’s book), Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals (with Jessica Pierce), The Animal Manifesto: Six Reasons For Increasing Our Compassion Footprint, Ignoring Nature No More: The Case For Compassionate Conservation, Jasper’s Story: Saving Moon Bears (with Jill Robinson), Why Dogs Hump and Bees Get Depressed: The Fascinating Science of Animal Intelligence, Emotions, Friendship, and Conservation, and Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence. The Jane Effect: Celebrating Jane Goodall (edited with Dale Peterson) was published in February 2015.

In 2005 Marc was presented with The Bank One Faculty Community Service Award for the work he has done with children, senior citizens, and prisoners. In 2009 he was presented with the St. Francis of Assisi Award by the New Zealand SPCA. In 1986 Marc became the first American to win his age-class at the Tour du Haut Var bicycle race (also called the Master’s/age-graded Tour de France). His homepage is marcbekoff.com and with Jane Goodall http://www.ethologicalethics.org/. Twitter @MarcBekoff

Thank you Utah: Another Cougar Relocation!

Thank you Utah: Another Cougar Relocation! It’s not surprising that a mountain lion would find its way down from Wasatch Mountain State Park and into the communities at the eastern base of the Wasatch Range. Like so many places in the American West, backyards and wildlands are just a stone’s throw – or a lion’s leap – apart.

It’s not surprising that a mountain lion would find its way down from Wasatch Mountain State Park and into the communities at the eastern base of the Wasatch Range. Like so many places in the American West, backyards and wildlands are just a stone’s throw – or a lion’s leap – apart.

“Everybody’s better off.”

“Everybody’s better off.” Our Resolve

Our Resolve

Listen Now!

Listen Now!

Maria Fotopoulos is a Senior Writing Fellow with Californians for Population Stabilization.

Maria Fotopoulos is a Senior Writing Fellow with Californians for Population Stabilization.